As Tipitina’s welcomes crowds for its yearly round of Jazz Fest shows, attendees will undoubtedly see the posters for old concerts that line the walls and rafters of the club, which first threw open its doors on January 14, 1977. Many are printed on the now-signature yellow shade of paper and lay out the performers for the night, but posters from the club’s colorful early days show that the marketing of its concerts then took on a more frenetic aesthetic.

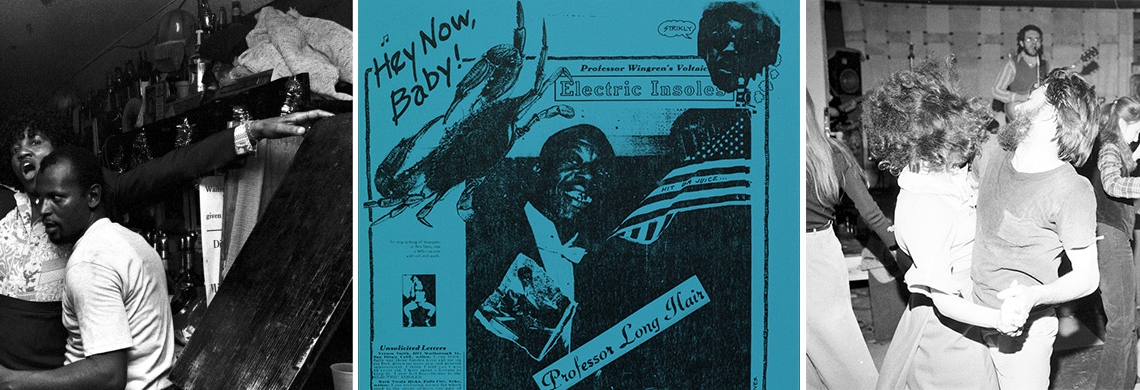

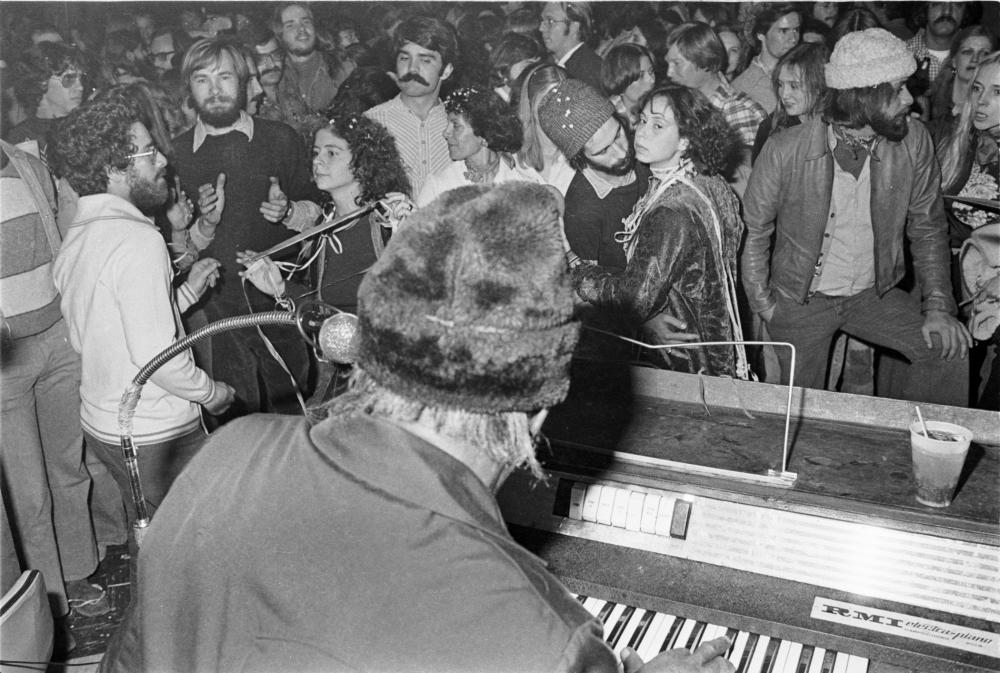

A couple dances at Tipitina’s in 1979. (Photograph by Michael P. Smith ©The Historic New Orleans Collection, 2007.0103.1.818)

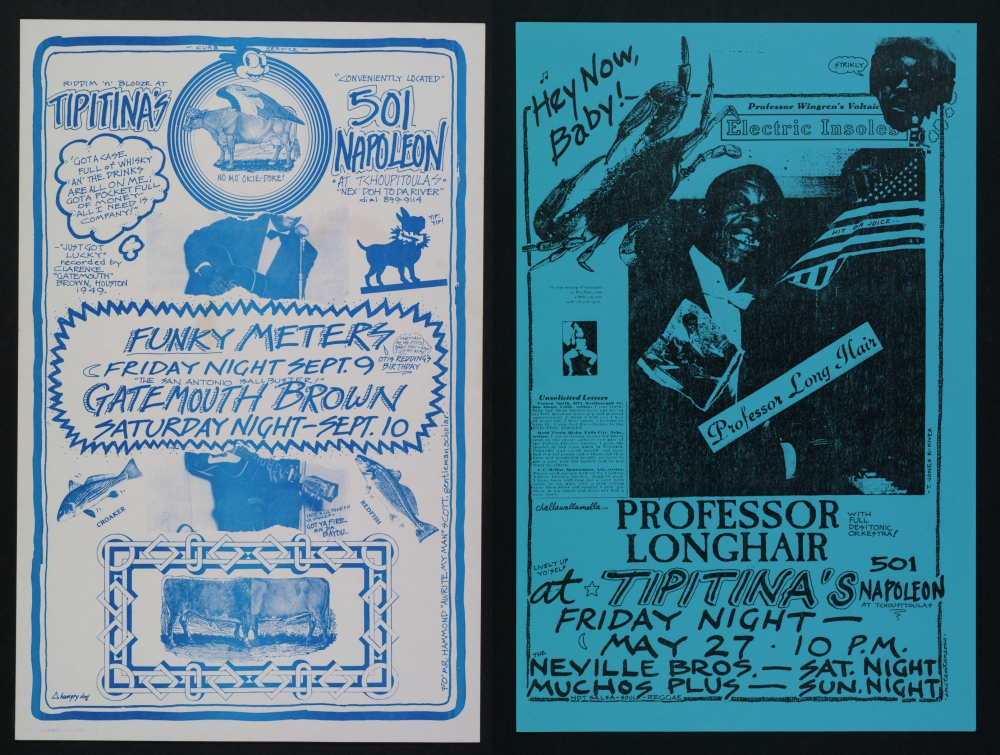

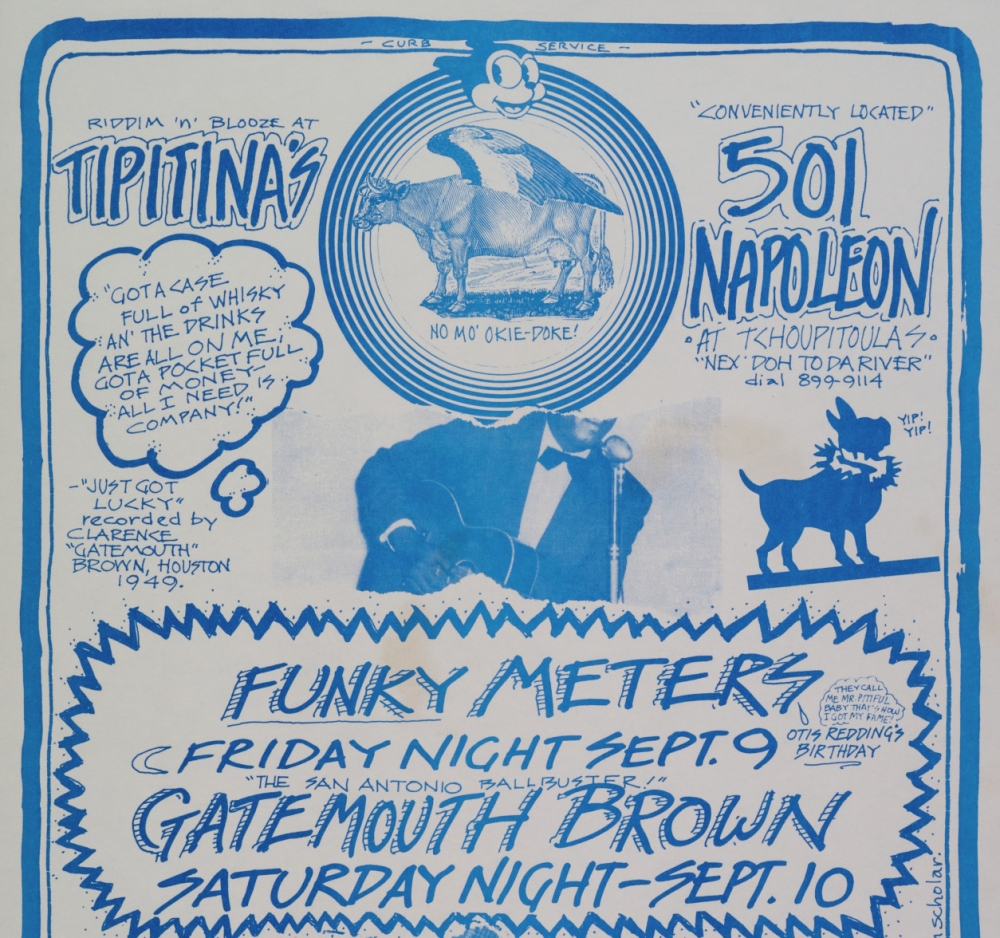

The poster for a 1977 Professor Longhair show includes a clipping from an advertisement for Professor Wingren’s Voltaic Electric Insoles, testimonials for said product, an image of a partially nude woman, a crab, and a cocaine-laced cure for mosquito bites. And, of course, it has an image of Longhair (born Henry Roeland Byrd), whose song “Tipitina” gave the club its name. Another from the same year advertises concerts for the Funky Meters and bluesman Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown. Animal imagery resurfaces, along with song lyrics and a tribute to Brown’s agent and WWOZ disc jockey Hammond “Awrite My Man” Scott, a “gentleman scholar.”

Through these items in THNOC’s holdings and interviews with two of Tipitina’s co-founders, we take a look back at Tipitina’s early years and the quirky materials that the club produced.

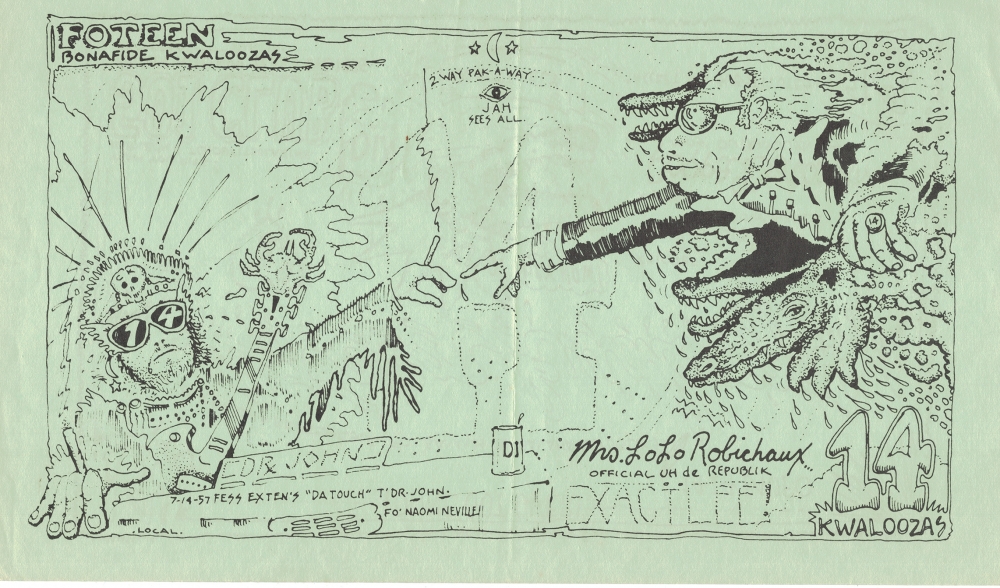

Two posters for early concerts at Tipitina’s use the same collage aesthetic. (Michael P. Smith Collection at THNOC, 2007.0103.7.9; 2007.0103.7.7)

The heady whimsy of these early posters reflects the tight-knit world of musicians and fans who frequented the club. Dotted with seemingly incongruous imagery, music lyrics, and vernacular phrasing, the advertisements hint at a communal setting focused on local music amid a swirl of alcohol and drug use.

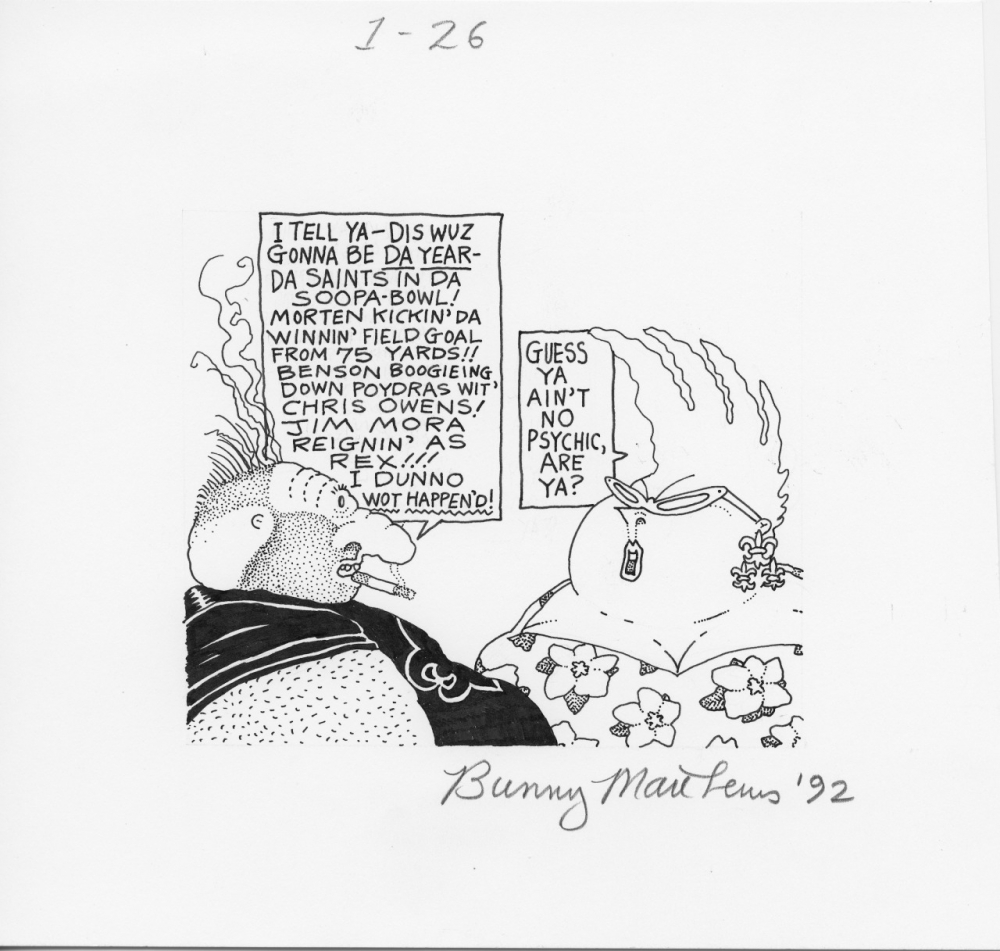

Artist Bunny Matthews created these two posters in the spring and fall of 1977, the first year of the club’s existence, according to Tipitina’s co-founder Steve Armbruster. The catchphrases—such as “down by da river” and “Riddim ‘n’ Blooze”—are reminiscent of Matthews’s popular comic work, such as his characters Vic and Nat’ly, who, beginning in the 1980s, came to embody the local “Yat” patterns of speech.

Bunny Matthews’s Vic and Nat’ly characters came to embody New Orleans’s “Yat” dialect. Similar imagery and phrasing can be found in the artist’s earlier work promoting musical acts. (THNOC, ©Bunny Matthews, 1992.39.15)

While the artist may be known, the inspiration for the posters is murkier.

The momentum for Tipitina’s existence started to gather years before its opening. In 1971 piano master Professor Longhair, a.k.a. “Fess,” reignited his career after several memorable performances at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival, a resurgence that coincided with a wave of renewed interest in Louisiana roots music. In the coming years, a group of music lovers, many of whom would later found Tipitina’s, built a reputation for throwing rowdy parties and dances, where their favorite local fixtures like Fess would perform.

Among these parties were Alligator Balls, which the group threw each year during large celebrations like Mardi Gras and New Year's Eve. Some of these events were held in the back room of a venue called the 501 Club, a cramped longshoremen’s hangout located at the corner of Napoleon and Tchoupitoulas. According to Hank Drevich, one of the Alligator Ball organizers and later a Tipitina’s co-founder, the off-the-wall marketing materials started there, with “Kwazolas,” fantastical ads that took the form of a $14 bill and featured a recurring alligator character and other local references. Drevich said that he and his friends would walk around and hand Kwazolas out to anyone they wanted to see at a party. The alligator character had its own back story.

An advertisement for an Alligator Ball, in the form of a $14 bill, features Professor Longhair and Dr. John in a reference to Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam. Bunny Matthews created this one and adapted the term “Kwazola” into “Kwalooza,” according to Drevich. (Image courtesy of Hank Drevich)

“There was this dance called Poppin’ the Gator, where you jump on the ground and kind of grind around,” Drevich said. “That spawned the Poppa Gator character, which was kind of a spoof of the big Mardi Gras clubs with his hat and bowtie. I think that worked its way into some of those early Tipitina’s ads.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the group of revelers bounced around different venues, from basements to public parks, and according to Drevich, the 501 Club was the only venue they were allowed to host a party more than once.

Professor Longhair plays for an audience at the 501 Club in 1976. The space was transformed into Tipitina’s the following year. (Photograph by Michael P. Smith ©The Historic New Orleans Collection, 2007.0103.1.530)

In 1976, the 501 Club was ready to leave the space, and over the course of a few months, 14 investors came together to incorporate, sign a lease for the space, and prepare to open a new club, which they would name Tipitina’s, after Fess’s enigmatic song. Finally, according to Drevich, at their New Year’s Eve Alligator Ball, the lessee of the 501 Club handed over the keys and bade them good luck. By January 1, 1977, the "Fabulous Fo'teen," as they were known, had a space where they could pursue their mission to bring New Orleans rhythm and blues back to prominence and give musicians like Fess a suitable place to perform. Their contributions totaled $14,000 to turn the two-room ground floor into a larger, open music venue.

“And we couldn’t even afford to feature Professor Longhair,” said Drevich. “Our first big event was the ‘Get Da Piano Dance’ with the Meters on January 29 to raise money for a piano.”

An image by Michael P. Smith shows the exterior of Tipitina’s in its early years. (Photograph by Michael P. Smith ©The Historic New Orleans Collection, 2007.0103.1.906)

An image by Michael P. Smith shows the exterior of Tipitina’s in its early years. (Photograph by Michael P. Smith ©The Historic New Orleans Collection, 2007.0103.1.906)

Those early posters, whimsical and defiantly unpolished, evoked the venue’s hand-to-mouth existence. The club’s financial situation was never assured. With just $14,000 in capital, amenities like air conditioning took a back seat to talent booking. Drevich helped manage Tipitina’s in its infancy, and noted that not all of the original investors wanted to be involved in the day-to-day operations. When it came to posters, Drevich would give Matthews the lineup for a show and the designer—unburdened by managerial oversight—took it from there, drawing from a vast collection of art, graphics, poetry, and old books.

“I once asked Bunny where he would get the things that he put on his posters,” said Drevich. “His shelves were lined with poetry, obscure histories, art books. He knew song lyrics I’d never heard of and played music himself. It was my first up close and personal experience with a real artist; to see him processing all that different information and putting it together so quickly in such fresh ways just blew me away.”

Armbruster echoed this sentiment: “They were always a source of delight and surprise. Why [Matthews] chose certain images, words, quotes, or whatever could have depended on what he’d just read or listened to, who he’d been talking to, wordplays on things he’d overheard, or saw in the newspaper. It may have depended on what he had for breakfast. Who knows?”

A detail from one of Tipitina’s early posters shows some of the imagery and phrasing that grew from the club's founders' shared mythology. (Michael P. Smith Collection at THNOC, 2007.0103.7.9)

The wording and imagery were rooted in the group’s shared mythology that stretched back to their Alligator Balls. According to Drevich, the animal iconography was grounded in the idea that the music and attitude grew from the Louisiana swamplands. Some of the phrasing came out of Ishmael Reed’s novels Mumbo Jumbo and The Last Days of Louisiana Red, both of which are steeped in the voodoo and hoodoo spiritual traditions of the African diaspora.

Whatever their discreet inspirations, the posters’ ecstatic style captured the raucous spirit of the new club. Stories from Tipitina’s in the late 1970s, told by the club’s founders, as well as early employees and patrons, swim with memories of all-night shows and larger-than-life personalities. As Art Neville remembered in a 2003 Gambit Weekly article, “Man, it was enchanted. It was the first place and the last place the original Meters (with Cyril Neville) played. We played 'til daylight a lot of times early in our career. It was like Mardi Gras every day inside the building.”

Dr. John plays at Tipitina’s in 1982. (Photograph by Michael P. Smith ©The Historic New Orleans Collection, 2007.0103.1.1118)

Local acts like Longhair, the Neville Brothers, the Radiators, Jesse Hill, Ernie K-Doe, and Dr. John all played Tipitina’s regularly and gave New Orleans a new place to celebrate its culture. The realities of business, Drevich noted, eventually toned down the club’s famously wild atmosphere. Still, he said, Tipitina’s managed to preserve much of “the spirit we rode in on.”

“In the early days, there was a feeling that this was our club, something for the city to enjoy,” Drevich said. “We didn’t look at it as a commercial enterprise.”

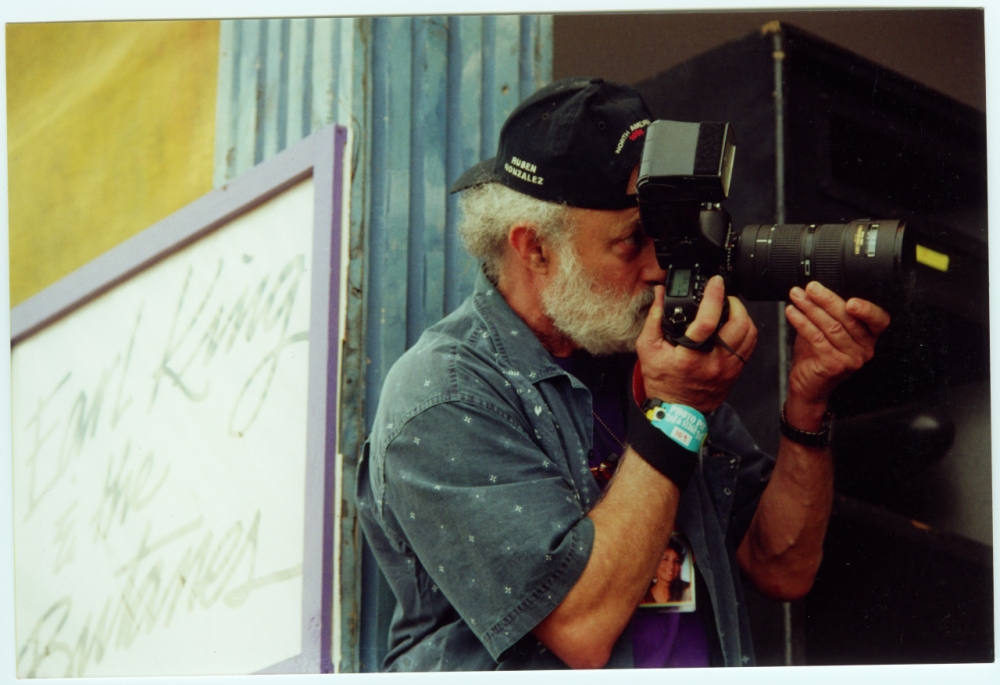

Images taken by culture photographer Michael P. Smith capture the club’s intimate and loose atmosphere in its first few years. A fixture on the music scene, Smith photographed black churches, second lines, Jazz Fest, and life around New Orleans and elsewhere. Other posters he collected, and some he had a hand in producing, carry traces of these early Tipitina’s ads. THNOC Curatorial Cataloger Emily Perkins explores his collection further in this companion article.

Michael P. Smith takes a photograph at Jazz Fest in 2001 or 2002. Smith was responsible for taking photographs and assembling a personal collection of ephemera from Tipitina’s early years. (THNOC, 2007.0103.11.29)

The posters, along with Smith’s images, provide a window into the grassroots beginnings of an establishment now brimming with international recognition. Advertisements for a show in 1978 assures readers that “the boogie will be abundant” at an upcoming concert. These relics of a looser era all but confirm that statement.

For a personal look at Michael P. Smith's collection of music posters, check out this companion article by THNOC Curatorial Cataloger Emily Perkins, and for more on the New Orleans music scene, visit THNOC's virtual exhibition New Orleans Medley: Sounds of the City,