New Orleans, typically thought of as a freewheeling and celebratory city, also has a more inglorious reputation for harboring pests. A recent report released by the American Housing Survey ranked New Orleans first nationally in this regard, standing out specifically for its hospitality to rats. These nuisances—specifically brown, or Norway, rats—have woven themselves into the fabric of this city like beignets and parade throws, and, a little over a century ago, their presence took a dark turn.

A group of men chase rats on the levee in New Orleans in the 1890s. (THNOC, 1974.25.17.135)

In the summer of 1914, a Swedish sailor in New Orleans died, and an autopsy revealed the cause to be the bubonic plague, long thought to be confined to the other side of the Atlantic. Known as the Black Death in the Middle Ages, when it killed roughly 25 million people in Europe, the plague is carried by infected fleas transported by rats. Increased trade between United States port cities and other countries around the turn of the 20th century introduced infected rats, and the first domestic plague outbreak happened in San Francisco in 1900.

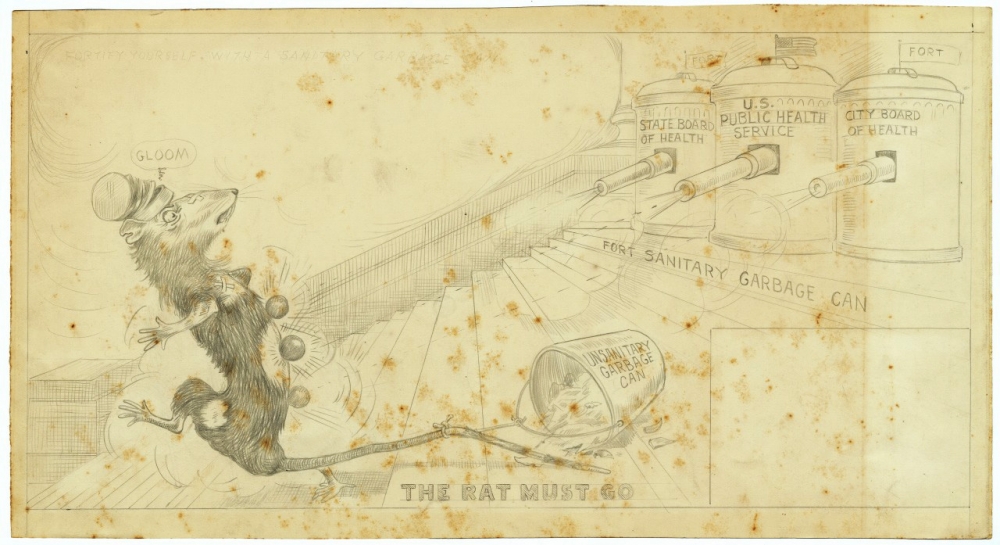

A 1914 political cartoon emphasizes sanitary garbage cans to combat rats. (Louis A. Winterhalder Collection at THNOC, 1985.71.22)

The plague in New Orleans had a less devastating effect than the Black Death. Thanks to a ferocious eradication initiative conducted by federal and local entities, its toll was limited to 31 infections and 10 deaths. From 1914 to 1915, efforts by the US Public Health Service in New Orleans led to the extermination of over half a million rats. Workers went so far as to level buildings and burn the contents of homes and businesses in order to control the contagion.

Noting the plentiful foodstuffs available at wholesale grocers, on ships coming into port, and in warehouses along the river, the Public Health Service decreed plans of action that included rat-proofing homes and businesses with concrete foundations and wire-mesh fortifications, fumigating ships with carbon monoxide, and setting out poison and traps for those rodents that survived other efforts. Additionally, the rat-proof garbage can was introduced to the delight of residents (and the consternation of the rodents). These steps, combined with an active trapping campaign, significantly reduced the number of pests and potential plague victims in New Orleans and became a blueprint for other port cities around the country.

Another political cartoon shows rats scrounging in open garbage cans. Authorities introduced a rat-proof garbage can to control the rodent population in New Orleans. (Louis A. Winterhalder Collection at THNOC, 1985.71.23 i, ii)

A second outbreak struck the city from 1919 to 1921, infecting 25 and killing 11, but thanks to the foundation laid by the successful response from a few years earlier, New Orleans was declared free of the plague—if not rats—by the late ’20s, and the disease hasn’t resurfaced since.

A version of this article previously appeared in the Historically Speaking column of the New Orleans Advocate.