If you’re walking down Bourbon Street on a sweltering August afternoon, you’re likely to be more concerned about the various substances puddling in the street than the infrastructure below it.

But beneath the opaque streams clouded by last night’s mistakes, there are stories waiting to be told.

So in June, when the city contacted The Historic New Orleans Collection to offer a section of pipe that was removed during the massive French Quarter Infrastructure Improvements Project, we jumped at the opportunity. What self-respecting history institution wouldn’t want a rusty, mud-caked hunk of cast iron that had resided beneath New Orleans’s most notorious street for more than 100 years?

Below, we’ve answered four questions that we know everyone will be asking—yes, the pipe is dirty—and sketched some of the fascinating narratives embodied in this artifact.

Why do we have it?

Crews work to lay a new water line in the 800 block of Bourbon Street on July 30, 2019. (Image courtesy of Eli A. Haddow)

On a recent walk over to the 800 block of Bourbon Street, where crews are placing a new water line, Hard Rock Construction’s Frank Thorning pointed to the deep ditch from which the historic pipe was removed.

“This was the more massive water line,” he says, referring to the recently exhumed pipe. “This probably supplied the whole of the French Quarter.”

Said pipe was no longer in use, and hadn’t been for a while. Sixteen inches in bore—pipe-speak for diameter—and made of solid iron, it was phased out by the first decade of the 20th century. Thorning and his colleague Chris Fontan think the changeover may have been prompted by the installation of streetcar tracks down the middle of Bourbon Street, directly above the original water line. Maintenance would have been difficult, as any leak would require crews to uproot the tracks to make the necessary fix. The new line was installed off-center, a few feet closer to the river.

Project superintendent Frank Thorning points to a pile of excavated earth riddled with railroad ties and sections of the 16-inch-wide cast iron pipe that used to carry water down Bourbon Street. (Image courtesy of Eli A. Haddow)

Project superintendent Frank Thorning points to a pile of excavated earth riddled with railroad ties and sections of the 16-inch-wide cast iron pipe that used to carry water down Bourbon Street. (Image courtesy of Eli A. Haddow)

Their hypothesis seems plausible. As an excavator unearthed feet-long chunks of pipe at the site, it uprooted railroad ties that sat about one foot below the modern-day street surface. The vestigial water line itself rested about four feet below the surface.

Even before they set out to remove it, Thorning and Fontan knew the pipe was old, but they weren’t sure how old. City records go back only as far as the Sewerage and Water Board’s establishment in the early 20th century, and all the records reveal is that an existing pipe was replaced in the 1920s. So the old pipe predated the S&WB—but no one knew for how long.

The city’s Deputy CAO of Infrastructure, Ramsey Green, wanted to make sure a piece of the relic was preserved, so he reached out to us. And voila, a piece of muddy, slightly corroded cast iron sits, at this very moment, in a secure museum facility, waiting for its time to shine.

When was it in use?

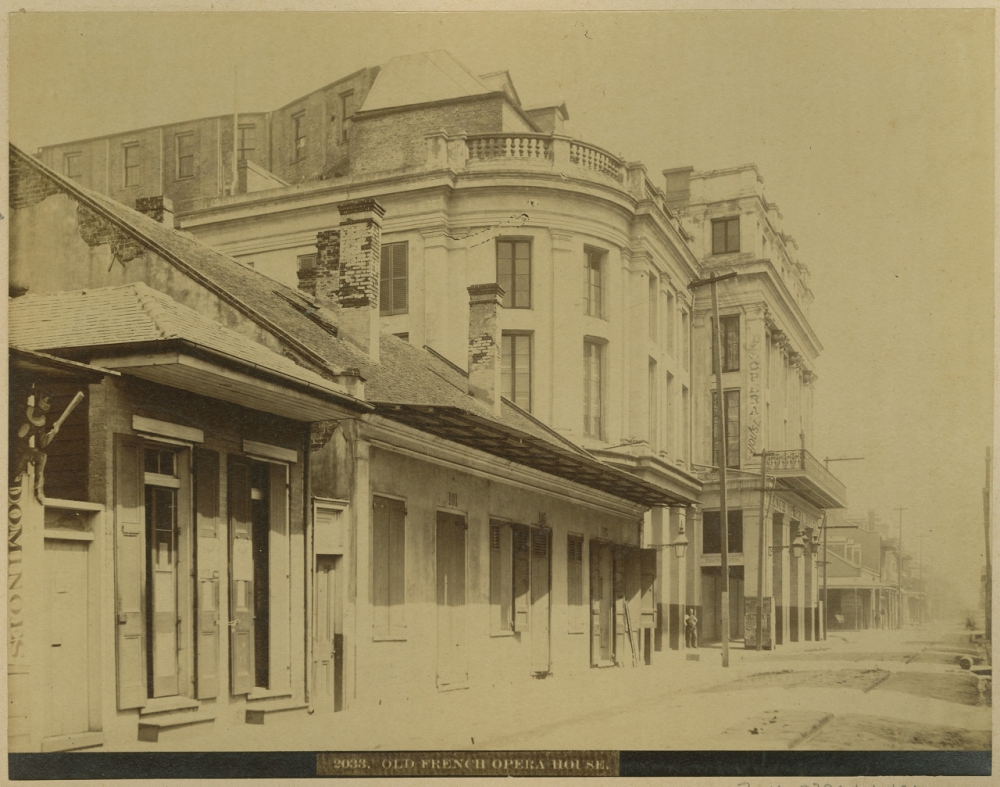

A photograph of the French Opera House shows Bourbon Street around 1889, about the same time that we believe the historic pipe was installed. (THNOC, gift of N. West Moss, 2016.0386.1.1.191)

While S&WB logs can’t tell us how long the pipe was active, other historical sources allowed THNOC Curator/Historian Eric Seiferth to narrow the range.

Seiferth was assigned to research the pipe’s history after the city reached out to THNOC in June. With the help of Sanborn fire insurance maps that show, in great detail, French Quarter properties and infrastructure during the 19th and 20th centuries, Seiferth concluded that the water lines were installed sometime between the 1876 and 1885 editions of the map. The 1876 version showed a 12-inch line running down the middle of Bourbon Street, while the 1885 version shows our 16-inch line in place.

That puts the pipe in the middle of a long and complicated history of subterranean infrastructure, one that today’s New Orleanians can probably relate to.

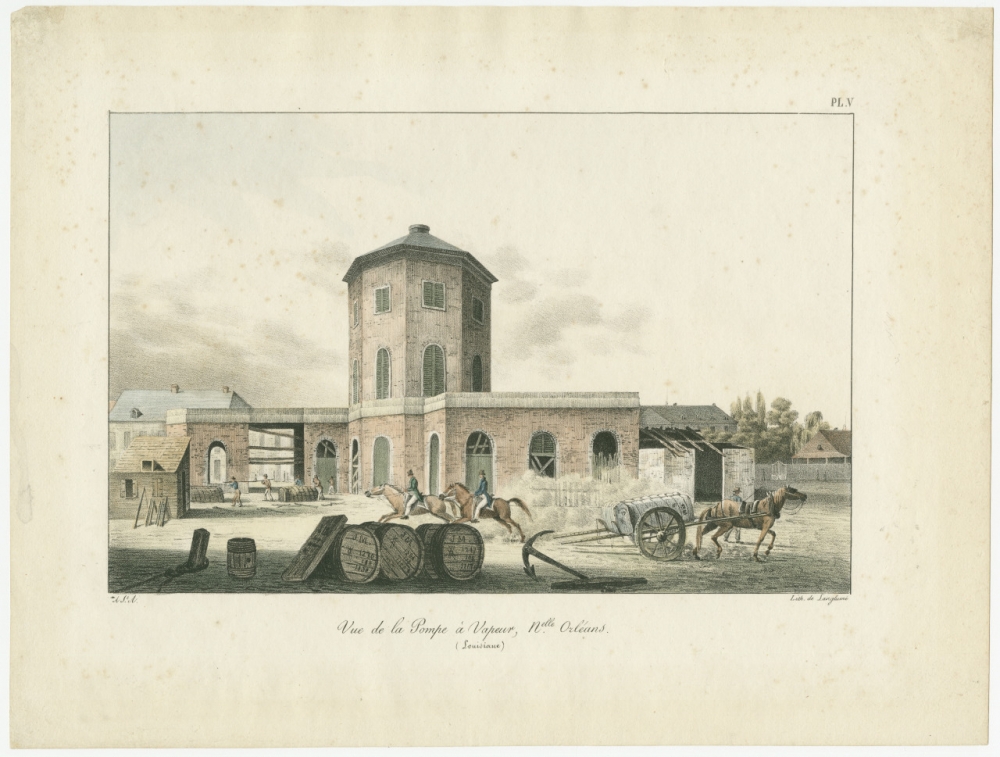

A circa 1821 illustration shows the pump house of the city’s first waterworks, designed by architect Benjamin Latrobe, which fed Mississippi River water into a network of cypress wood pipes. (THNOC, the L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1937.2.5)

As it turns out, running water in New Orleans has been a running controversy since rudimentary pipes were first installed in the early 1800s. That’s when famed architect Benjamin Latrobe—also known as the original architect of the US Capitol building—was tasked with installing the city’s first waterworks. Fashioned out of hollowed-out cypress logs, Latrobe’s system conveyed water from a pumping station situated on the Mississippi River, but it didn’t work too well.

At the time, most drinking water came from rainwater collected in cisterns or from wells. The pumped-in river water was used primarily to flush the city’s unpaved streets of filth, an effort that, in its early days, actually flooded some homes with a murky tide of the French Quarter’s refuse.

After Latrobe’s death in 1820, the system changed hands a few times, alternating between city control and private monopolies. By 1869, a city report bemoaned the waterworks’ “very dilapidated condition, from a long neglect of current repairs.”

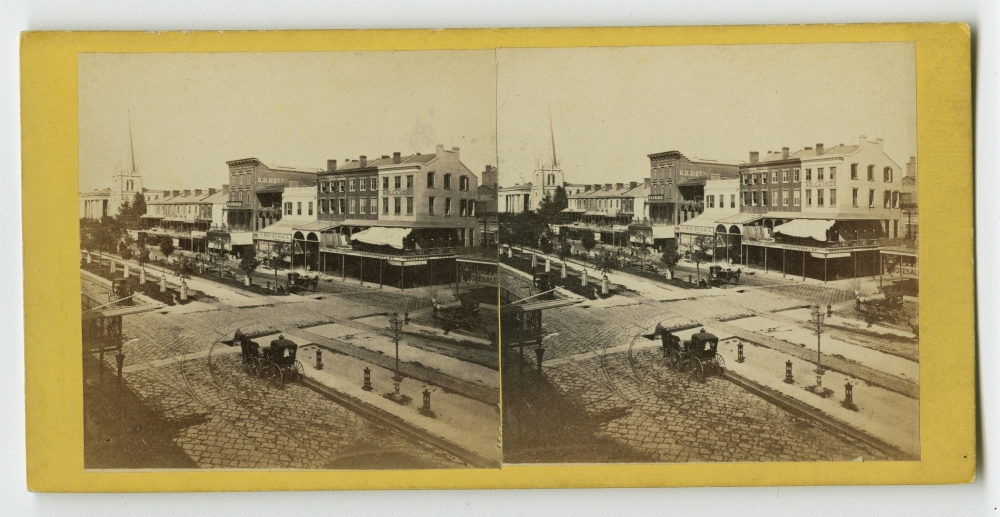

An 1866 stereograph shows Canal Street, three years before the city labeled its waterworks “in very dilapidated condition.” (THNOC, 2010.0095.16)

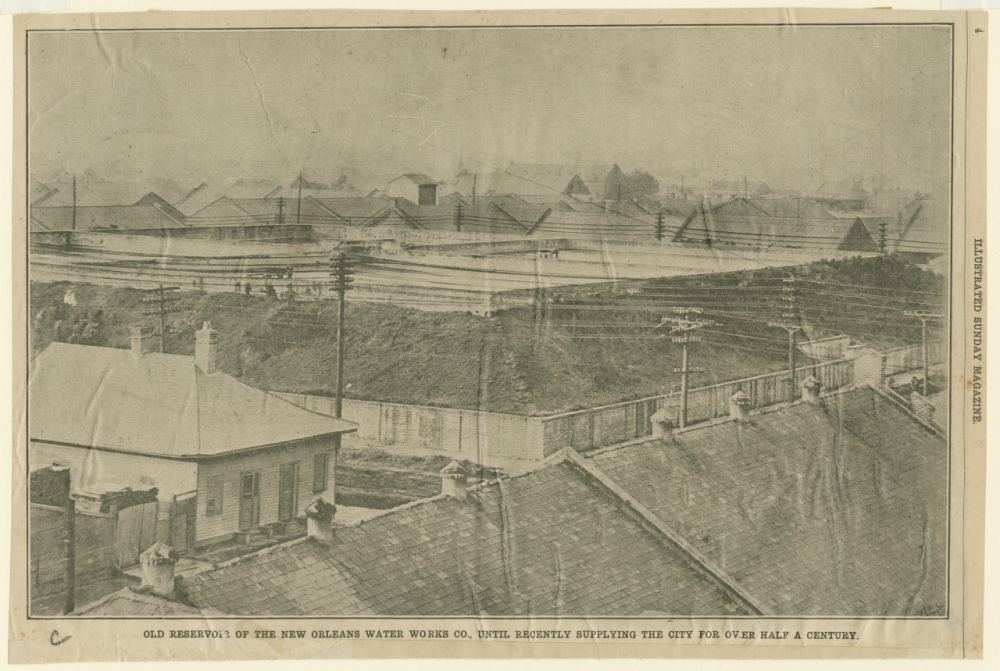

In 1877, around when our pipe was installed, the city handed control to the New Orleans Water Works Company. Its charter required the company to install new pipes throughout the city and to repair the Lower Garden District reservoir that provided the city with its water. By 1886, the company had succeeded in laying 70 miles of new pipe and rebuilding the reservoir, providing enough pressure to power freight elevators downtown.

This investment foreshadowed an infrastructure boom that would radically transform New Orleans in the coming decades.

An illustration from the early 20th century depicts the reservoir used by the New Orleans Water Works Company. The Lower Garden District structure served the city its water from 1836 until the Sewerage and Water Board built new infrastructure in the early 20th century. (THNOC, 1974.25.13.269)

“This is right after the Civil War and Reconstruction,” says Seiferth, speaking in his office at THNOC’s Perrilliat House. “The local economy is starting to rebound, and in the coming decades, the city’s urban geography starts to transform into the place we recognize now.”

Come the 20th century, infrastructure improvements allowed the city to expand greatly beyond its historic core. The modern drainage system opened up entire low-lying neighborhoods—Mid City, Lakeview, Broadmoor, and Gentilly, to name a few—to habitation; streetcars were electrified and came under a single system; and potable tap water curbed bouts of yellow fever and cholera that plagued the city through the 19th century.

“I think infrastructure improvements like this one allow us to talk about the emerging modern city in the 20th century and what that looks like,” says Seiferth. “And it’s great that this pipe came from the French Quarter, where the system had existed since the 1820s and was undergoing yet another overhaul.”

Who was using the pipe?

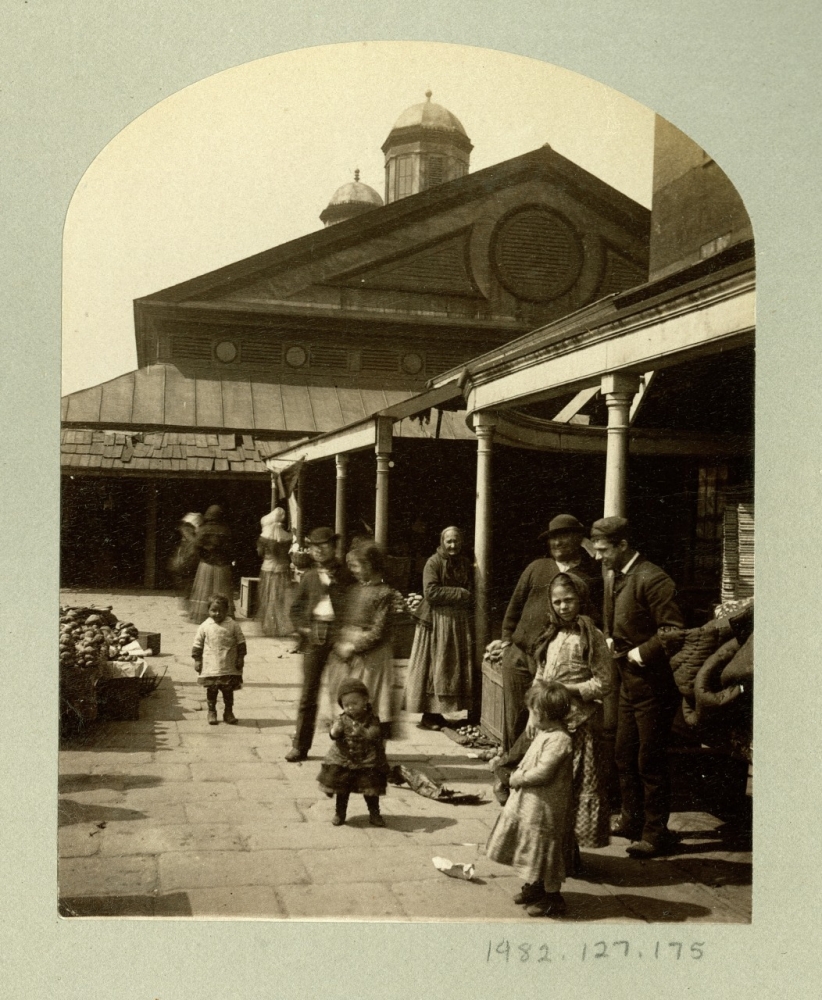

A photograph by Edward L. Wilson shows people in the French Market in 1884 or 1885, around the time that the recently removed pipe was installed. (THNOC, 1982.127.175)

When our 16-inch pipe was installed on Bourbon Street around 1880, the surrounding neighborhood was in flux, as older residents decamped to developing neighborhoods and new arrivals to the city began settling in the French Quarter.

“Much of the wealth and capital previously associated with the French Quarter was leaving the area, as new neighborhoods were being developed away from the old urban core,” says Seiferth. “By the latter 1800s, the remaining population of Creoles in the area was predominantly aged. Added to that were newly arrived emigres from Europe. You would have had a kind of a mixed ethnicity working neighborhood.”

Another image by Wilson shows African Americans on a French Quarter street in the 1880s. At the time, the Quarter was an ethnically diverse area and among the most high-density neighborhoods in the city. (THNOC, 1982.127.177)

And at the time, it was one of the more high-density residential sections of the city, though little had been built or updated there since the antebellum years. By the 1880s, the neighborhood’s decades-old buildings were past their prime and being converted from single-family homes into multi-residential apartments, Seiferth noted. Meanwhile, the city continued to expand upriver, with glitzier homes going up in neighborhoods further uptown.

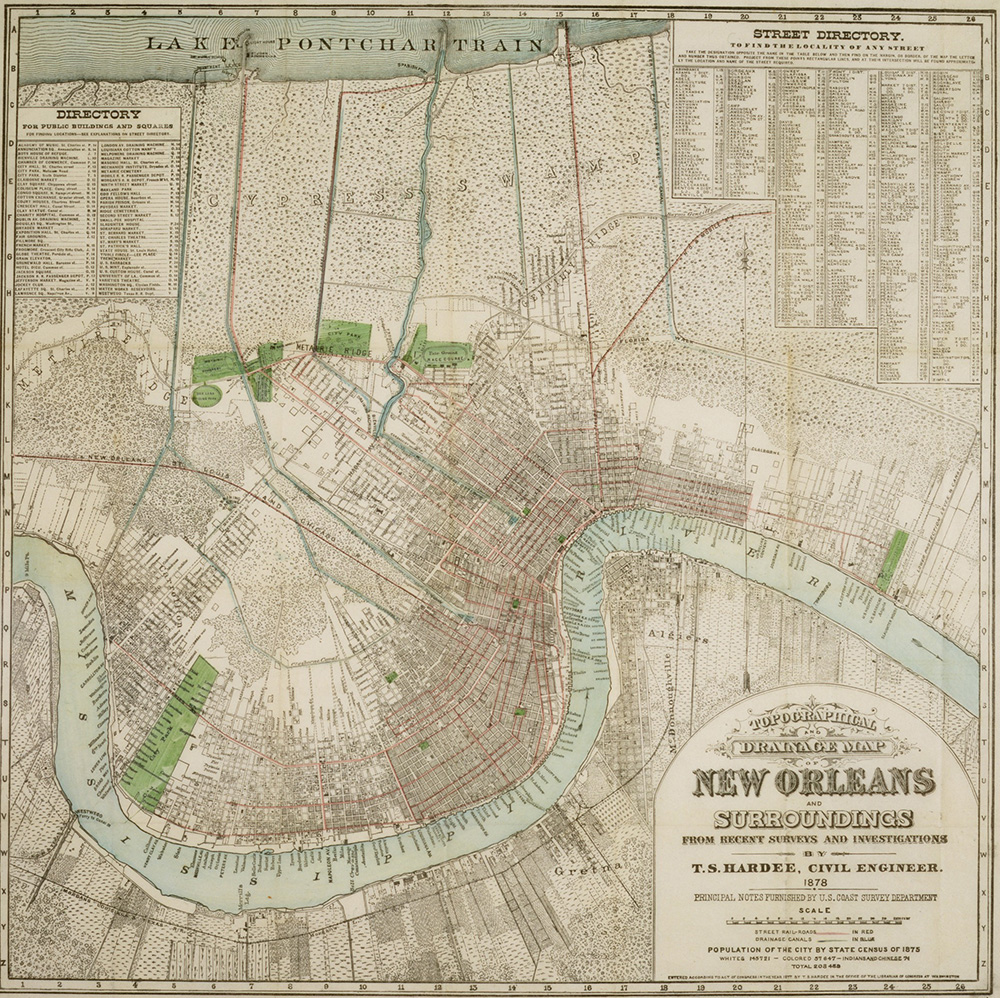

An 1878 map by civil engineer Thomas Hardee shows that New Orleans's street grid was concentrated mostly along the Mississippi River, with some development toward modern-day Mid City. Low-lying neighborhoods like Lakeview, Gentilly, and Broadmoor were still swampland at this time. (THNOC, 00.34 a,b)

The New Orleans Water Works Company’s main concern, according to historian Carolyn Kolb, was ensuring that its business clients were well served, as they paid the highest rates. The company was said to shut down water at night, when its businesses weren’t using it; charge high rates; and disregard the needs of the poor. Kolb notes that the company was a frequent target of public ire—and, in a move that would be familiar today, its perceived greed was lampooned by a Mardi Gras krewe in 1881.

In the early 20th century, after a legal lengthy battle, the newly formed Sewerage and Water Board was able to bring the system under city control. Yet despite certain improvements, criticism of the system continues to this day.

What will we do with it?

This image, taken by city archaeologist Michael Godzinski shows the pipe before it was transfered to THNOC. (Image courtesy of Michael Godzinski)

Seiferth notes the complications of accessioning and displaying a piece of archaic infrastructure. It’s big, it’s dirty, and it’s ugly, he notes. But it gives THNOC the opportunity to present visitors with a tangible piece of a system that few think about, until something goes wrong.

“New Orleanians have this relationship with our infrastructure, specifically our water delivery system and water removal system, that is very contentious,” says Seiferth. “We rely on this type of infrastructure. Sometimes, it’s not working as well as we want, or it’s older than we want it to be. Showing a piece of old infrastructure allows us to talk about all of these advancements.”

After some conservation (the pipe shows signs of oxidation) and cleaning (it’s caked in dirt) Seiferth hopes it can go on display, so that visitors can engage more directly with the ever-unfolding story of the city’s infrastructure.

As for the specific location where it was found?

“Is it more disgusting because it was running under Bourbon Street?” asked Seiferth. “No not really, anything that far underground is pretty dirty.”

So watch your step around those murky Bourbon Street puddles, but don’t forget the complexities of what lies beneath.

See our related story about a wooden water pipe that was also recently acquired by THNOC.