The Calliope Public House Development

Shelia: In in the Calliope Project, we were always surrounded with music. My mother, Naomi Gibson, used to go do that old school feetwork.

Gregg: I knew Shelia in a roundabout way because we were friends of other friends out of the Calliope. We grew closer as friends—almost like family—when I became associated with her grandfather, Mr. Frank Parker, who was a musician friend of mine. Prior to becoming involved with traditional jazz in New Orleans music, Mr. Parker played with a lot of musicians like Ray Charles and Louis Jordan. He came home and led his own trio at the Fairmont Hotel with his wife at that time, Laverne. She played the piano and sang, and Frank played drums. He was very close friends with a gentleman by the name of Herman Sherman, who was the leader of the Young Tuxedo Brass Band. I met Frank through Herman. We were all in a circle of musicians. I played with the Young Tuxedo, and eventually became the band leader.

After the demise of Cy Frazier, Mr. Parker was asked to come and play with the Preservation Hall Jazz Band. During those days, I used to go to the Hall at least two or three nights out of the week to listen to Percy Humphrey’s band, which Frank was a member of, and sometimes Kid Thomas and Kid Sheik’s bands. The nights I would go and listen to Percy Humphrey’s band, Frank and I would go across the street to Johnny White’s on his breaks to have a few drinks and talk about the music. When he suffered a stroke and couldn’t play anymore, I would periodically go and visit him in New Orleans East. You know, drop a few dollars on him, just to show the love and friendship that we had for one another up until his passing.

Shelia: My mother was raised by Frank Parker’s grandmother, Bertha Jones—the same lady who raised me. She was from Uptown around Willow Street and the Baptist Hospital area before she moved into the Calliope Projects. When she passed, I was raised by her daughters. During the week, I stayed with my great-great-aunt Bertha in the Calliope to be close to school, and on the weekends, by my great-grandmother, Isabella, in Hollygrove. A lot of known citizens of New Orleans, from superintendent of the police and congressmen, came out of the Calliope.

Gregg: It was a hub site.

Shelia: Like family. When I was a child, they had a newsletter they used to put out about activities going on in the neighborhood like the garden club. The hanging spot for the kids was Rosenwald Recreational Center. They did bring it back after Katrina. We’re grateful for that, cause it’s like one of our landmarks.

Gregg: Broad and Earhart Boulevard. The Mardi Gras Indians used to dance through there on St. Joseph’s night.

Shelia: It was a place where the kids could go. Mr. Morris Jeff was in charge of NORD then. They taught us sports. That’s where I first fell in love with ballet and tap. I started dance at Durham Junior High and proceeded to dance at Booker T. Washington, and during college at Southern in Baton Rouge. After graduating from college when I was 22 years old, I started teaching. I’ve been teaching almost all of my adult life. As a teacher, I wound up having majorettes and flag twirlers because I was a majorette myself.

Cultural Education

While I was growing up, my mom lived in California and New York. She didn’t raise me until high school. She did a little bit of everything for work, but eventually, she wound up being a paraprofessional in the school system. She was like a teacher’s assistant working with special needs kids. I felt I lost a lot of time with her. When she came home, sometimes there were things I wanted to do with her, but she was dealing with others because my mom is where everybody went. My mama took in everybody. She had an open-door policy. Never locked her door. She didn’t care who you were.

Gregg: She would feed you. When I did my Mardi Gras party, she cooked the red beans and rice. Other people cooked red beans and rice, but everybody would say, “I want Ms. Naomi’s beans!”

Shelia: One time, my friends came down for a James Brown concert at City Park, and they all stayed with my mom. We were sleeping everywhere. I had one young man who was from Michigan, and he said he never had white beans, so my mama went out her way to cook them for him so he could see what they tasted like. Another time, I remember for Greg’s club, my mama cooked almost close to 20 pounds of red beans in a big old pot. And she was a short lady—like 4’11”.

Jackie: Yeah, she used to have to stand on a chair.

Shelia: A little step ladder in our kitchen.

Gregg: Young Men Olympia had their anniversary that year, and after the parade the guys came to my house, and some of them went to Kemp’s.

Shelia: She believed in eating, and she’ll feed a stranger. She would not turn nobody away.

Jackie: I am the daughter of Louise Searles King Parker, and the baby sister of Naomi Louise Parker Gibson. At an early age, I was adopted by family members who lived in the Carrollton/Hollygrove area. My education was in the New Orleans and Jefferson Parish school systems. I was a modern dancer, and I took up tap in school. I graduated from L.W. Higgins High School. I was influenced by my cousin, Walter Searles, and my brother, Reverend Earl A. Moon, to go into funeral services. I moved to Texas to attend Commonwealth Institute of Funeral Services.

When I returned to New Orleans, they weren’t hiring Blacks then. Black-owned funeral homes like Rhodes weren’t hiring either. Walter, who was what you call passé blanc, worked all those years for Louisiana Undertaker, but I was a little bit too dark—they wouldn’t hire me. My parents decided I need to change my field. By me being the caretaker in the family, they told me they wanted me to get involved in nursing. I became a CNA in nursing homes in Jefferson Parish. And then I began doing private sitting before I took a job at the Carrollton/Hollygrove Senior Center. When I retire, I’m thinking about going back into the funeral business. I want to do something like that or hospice just to keep me busy.

Gregg: Oh, you’ll be busy! [Laughter]

Jackie: My sister Naomi introduced me to the culture. I was more of a bookworm than anything else and my sister’s house was my freedom. I came from a strict household from Monday through Thursday. On the weekend, I got with my sister, and we would do something different. I remember the first time she took me to a parade, she said, “I’m gonna take you to a pluck.” I was just blown away by the unrestricted dancing. Afterwards, every weekend, I’m asking, “Where we going?” Our nights usually included Rose Tavern.

Gregg: It was an institutional landmark.

Jackie: For me, it was cultural education.

Shelia: It was like the project’s home club. Everybody who lived in the project that was old enough to go to Rose Tavern went through. Even a lot of other clubs tried to pass by Rose Tavern to see what’s happening cause it was a known club!

Gregg: I was just looking at a route sheet that was posted in the Dancing in the Streets exhibit and it showed the route of the Avenue Steppers parade where they stopped at Rose Tavern.

Anybody from Uptown, Central City, you ask them about Rose Tavern, they’ll know.

Shelia: They knew my mother, too. From the Magnolia Project, back in Hollygrove, to downtown Seventh Ward, my mama was a well-known lady in the city because she enjoyed life.

Mapping Parade Lineages

Shelia: My mom got started in second lines when my brother, Roque “Rock” Caston, began parading with the Scene Boosters when he was around seven years old. My mama was the president of the mothers of the little boys who paraded. They had their own banner. Later, she paraded with the Calliope High Steppers. My cousin, Johnny “Kool” Stevenson, was the founder. It was a big group.

Gregg: Johnny Kool had been a member of the Scene Highlighters. A lot of the members of that club were intertwined with the Avenue Steppers. Johnny Kool was one of the original members with the Black Men of Labor also. Black Men of Labor invited everybody from all across the city who was interested in getting the old music back on the street. Johnny Kool and some members of the Jolly Bunch were about that, so they paraded with us that first year.

Shelia: My grandfather, Frank Parker, was a part of their club, too. He rode in the buggy as an honorary member.

Gregg: We made all the older musicians honorary members. They rode in the parade with us paying tribute to them for all the years that they were part of the musical scene. We put on that first honors program for them, and they were so appreciative of it.

Shelia: My mother’s ladies group got started when she was sitting on the back stoop with her neighbors. They used to love sitting back there. They decided to call themselves the Jetsetters, as a play on words because the project was called “the jets,” too. When the Calliope High Steppers no longer paraded, my mama broke into her own.

We chartered our club and had to apply for our own date. That knowledge came in with Johnny Kool, as well as Norman Dixon, Sr. and Alfred “Bucket” Carter with the Young Men Olympia. My mother and Bucket were like sister and brother. Like Bucket, she never stopped parading.

Jackie: Originally, there was a men’s division of the Jetsetters, but it faded away.

Shelia: I didn’t originally start with my mom and them. I was in college and teaching. Then I got married and had a kid, so that was my lifestyle.

Jackie: The first years of the club, you had seamstresses. Our favorite store to get our material was Krauss on Canal Street. My sister was very structured and adamant about things being done decent and in order, so we had a businessperson, Rebecca Glover Brown. We also had bylaws: To promote love, good spirit, loyalty, and fellowship among the members of this club. By the source of historical information, establish a marching club for its members participating in parades and cultural events to give back to the community in forms of charity such as helping homeless women, children, and domestic violence.

Shelia: We used to have fish fries, bus rides to the casinos and…

Jackie: ...and a lot of festival rides to places like the Ponchatoula Strawberry Festival.

Shelia: We took the children.

Gregg: Experience.

Jackie: The Lady Jetsetters gave every band in the city a break. My sister believed in spreading the love.

Shelia: We started with Rebirth and had Soul Rebels. The Stooge Brass Band became our main band unless they were out of town and then we used Hot 8, New Generations…

Gregg: To Be Continued.

Jackie: A lot of times, when it came to the stops, the bars didn’t patronize the band, they would only patronize us as the club. We had what they call a refreshment car, and that car had chicken sandwiches, cold drinks, and beer for the band. The night before the parade, my sister made sure that was in order, so when we had a stop and the band couldn’t go in, they would be fed.

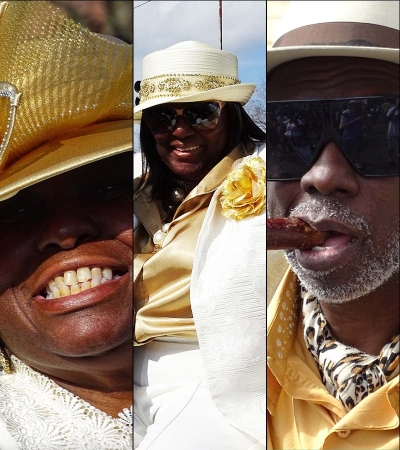

Lady Jetsetters Royalty

Jackie: We have a king every five years. We don’t have a queen because we’re a female club. We don’t do the float thing. We do the old school, traditional second line with the king and queen court on antique convertibles.

Gregg: The Lady Jetsetters asked me to become their king in 2004.

Jackie: Why did we ask Gregg to join us in 2004? The style, the pizzaz! And by him being just a friend of the family and a loving person.

Shelia: And then he was a part of the culture.

Gregg: It was a beautiful day. The skies were blue, the sun was shining, the temperature was just great for a parade. They were dressed fabulous. They had on this pea green outfit with fur collars, and a beautiful green hat. They were so elegant. I dressed in a white tuxedo and had my little crown. At the end of the parade, I changed clothes to a cobalt blue, double breasted sport coat with pea green jeans. And let me tell you, I was out of the car more than I was in the car, cause I was dancing with them.

Jackie: That’s one thing about the Jetsetters’ kings, they don’t never stay royal. They like to get on the street, and they like to dance.

Gregg: You know, it was kind of strange in a way I was the last king before the storm hit in 2005. We started at the great Rose Tavern. And that’s where we ended.

Shelia: That was our home club. From Rose Tavern, we went to…

Gregg: Martin Luther King, then Simon Bolivar to First Street, take a right on Baronne, and turn onto Second Street to Second and Dryades.

Jackie: Stop at the Sportsmen’s Corner.

Shelia: Then Bean Brothers.

Gregg: And then sometimes y’all would go all the way to Louisiana and stop by the Sandpiper.

Jackie: The route would change according to who’s open, and who would give us authority. We wouldn’t just go into people’s bar and say, “We want you all to give us a stop.” We asked the bar owners to give us a signature so that we know that it was qualified for us to go in there.

Shelia: To give us permission to come with our club.

Gregg: When I was king, we didn’t go down Louisiana Avenue. We hit Washington Avenue and went through Magnolia Street where Eldora “Dee Dee” Harper used to live.

Jackie: She had known my sister for years. She had been the queen of the Scene Boosters’ parade in 1983 when Naomi was with the club.

Shelia: Usually we don’t make that cut, but after she passed away, we paid homage to her because she was important in the second line environment.

Gregg: She was an iconic individual in the Magnolia Project. Anybody who went to jail, she knew who to talk to. She would get word to parents when something went wrong. She was also the queen of the Creole Wild West tribe. When I was a kid, the first woman Indian I saw was Dee Dee. I was standing on the corner of First and Lasalle, in that curve by Simon Bolivar, and I will never forget how she came around that curve by Simon Bolivar with a canary yellow suit. She had this very dark, coal black complexion. And smooth. She was a strong supporter of the Avenue Steppers and the Scene Highlighters, and the president of the Fun Lovers.

Shelia: My mama was close knitted with the Scene Highlighters, too.

Gregg: From Dee Dee’s, we went to Silky’s. Then we stopped at the daiquiri shop on Claiborne and hit two bars along Washington Avenue—Fox and Hollow Point—that are across the street from one another.

Jackie: One year, we had time and had a street-wide “Bus Stop” line dance.

Gregg: The Jetsetters were the first one to do that on the street.

Shelia: Everybody else started copying us, trying to get a routine together. But we had the whole street. Washington and Galvez be lit up. For many years, Raymond owned Rose Tavern. When he passed, his wife took over the club. Then when she passed away, the daughters tried to maintain it until Katrina hit.

Jackie: The Lady Jetsetters met with the family to find out exactly what they were going to do about it because they had artifacts on the wall with peoples’ names on it, and a lot of memorabilia was there, but the kids decided that they wasn’t going to bring it back.

Shelia: Finally, it got torn down and they built a home there. My mother was able to get one of the new apartments when they rebuilt the Calliope as the Marrero Commons. She was outspoken with the Calliope back then. She was a real activist. Her house became our home place. After the Rose Tavern was closed down, we started coming out at her house at the start of the parade.

Retiring the Club

Shelia: We had the best parades. We always had sunshine. We never had trouble out of the thirty years that we paraded. We had so many people on the street and never had problems, but that all stemmed out of love and respect for my mother.

Jackie: My sister didn’t believe in anything last minute. She believed in your clothes being hung. If your fans are being made, she wanted them in the week before. That Saturday before, she be going to the presser. When Rebecca Glover Brown retired, Shelia started doing more of the business manager duties. Our club always parades with a theme. We brought a theme to the table and then called Shelia to tell her what colors and style we’re looking for.

Shelia: I came to be their designer. After I picked out what they were going to wear, I brought it back to the club, and the club voted on it.

Jackie: After we get it all together, I told Gregg what the colors were, and he’ll do his own thing.

Gregg: All I need is the colors. I try to dress as neat as I possibly can with the colors that they give me. After that first year when I paraded with them as their king and I saw them with that fur around their neck, I knew I had to come right every year.

Shelia: Everybody was waiting on the Lady Jetsetters and Gregg Stafford. He’s the only man we let get out on the street and party with us.

Gregg: In YMO, I’m grand marshal of the First Division, and I am one of the founders of Black Men of Labor. With Lady Jetsetters, I stay within my limitations because I’m not the king but I’m a former king, so I try not to overshadow them and like to stay in the division, do my thing, and dance.

Shelia: My mom’s health started going down, but she was still involved with the parade; she just wasn’t on the street.

Jackie: The year she rode on a car, we wore black and white glen plaid, and silk, and brought the parade back to the Calliope. On the route sheet, I put “Displaced But Not Destroyed.” Everybody who was displaced from the Calliope came back, and we just made it a whole street party. You see people you haven’t seen in a while on the street, and you’ll be like, “We home!”

Shelia: That was the last parade we did with my mother. When she passed, I was with her at her house. The band members came and struck up the music, and they were second lining in the backyard, all on Earhart. She had a sendoff.

Jackie: She had a second line every night.

Shelia: We had food every night—the band, food, the band, food. It was just how she lived her life. Markeith Tero, who works at Professional Funeral Home on North Claiborne, called my mama “Auntie.” He took care of her body. At her viewing, we displayed the Scene Boosters’ Mother Club banner and her flag for the Lady Jetsetters. Those who wanted to visit came through, and we had a second line band. Then I took her to my church, City of Love back on Palmetto, for the funeral and the church was packed.

The year after she died, Jackie was living Baton Rouge, and I was trying to organize some of the younger women to carry on the club. I told them, “I’m just the administrator. If any Lady Jetsetters business needs to be taken care of, my mama put my name down to do that, but I’m stepping away for organizing the parade. You all pick your own officers and see whatever fundraisers you want so you can get your band money together.”

Jackie: For years, we followed an old school dress code.

Shelia: We have a certain decorum on the street. We have a rule, if we have on blazers and it’s getting warm, we’re all going to come out the blazers at the same time. You don’t start undressing and getting out your clothes when the parade just started.

Gregg: But some younger people are from that “Do Whatcha Wanna” generation.

Shelia: The Lady Jetsetters believe in doing things decent and in order. People were talking, too. We got the feedback.

Jackie: We listen to the people.

Shelia: For our 30th Anniversary, they didn’t think I was gonna do it, but I showed them that I did!

Jackie: We pulled it off.

Shelia: Our last parade was just Jackie and me, with Gregg. We wore our gold and our cream. We going out in style. I gave my mama her 30th anniversary with dignity and respect.

Jackie: It was a little discombobulated without my sister.

Shelia: But we had our route, our stops, and did what we had to do. I rode in the car with a big portrait of her.

Jackie: And Gregg and I we were on the street. It went off.

Shelia: After the parade, I retired the club.

Jackie: We gave our Sunday back.

Shelia: I wrote the city and told them. When things start getting better with the Covid, then we will retire the banner. With our long history with the city, we hope they will find a date for us. We might invite old members who were really part of the club for years. They’re up in age now, some of them. Even if they just drove in the car to make the parade a celebration of the years the club has been on the street. If we can’t, then we’ll have something at a venue and do our celebration there to put the banner to rest for good.