Memorial Day Weekend

Jarrett Johnson: Our parade is on Memorial Day weekend. People are usually off that Monday.

Kasey Batiste: They are out and about.

Jarrett: On our route, there’s a big crowd under the North Claiborne bridge. It’s also the same day as the Zulu elections, so North Broad Street is crowded, too.

Ada Robertson: Our whole weekend is a highlight for me. The Friday before our parade, we get together, and then you have that Saturday to rest and do your last little preparations.

Jarrett: Before the parade, we go to St. Jude or St. Peter Claver Catholic Church. We give a donation and go to the altar to be blessed by the priest. We have breakfast at Betsy’s Pancake House before we hit the streets. We draw an interesting—

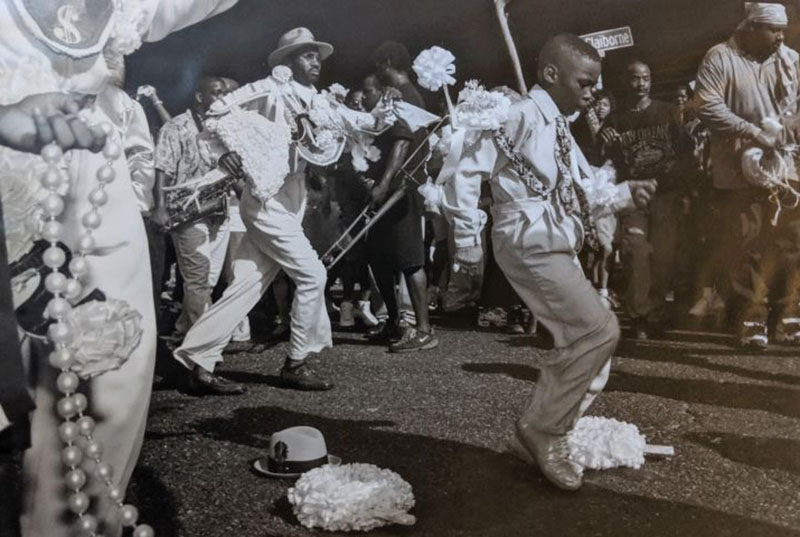

Ada: Turn-out. Most people follow the whole parade. Even though it’s hot, they still party and have fun.

Jarrett: We have a lot of older people who’ve been watching the parade for years and years. And that’s cool because they can tell you stories, “I remember when.” The late Ms. Catherine Henry, who died when she was over 90, never missed a Money Wasters parade. We also have people who come from out of town every year. I talked to one white guy about it, and he said, “I just love this. I’m always interested in coming to see the Money Wasters.” That’s a really neat thing to me because I grew up in the Sixth Ward—we were raised around the parades.

Sixth Ward Stories

Ada: I grew up on 2206 St. Ann and North Galvez with my parents, Audrey and Joe. My mom was a housewife for a while until she went started teaching early child development. My daddy worked at Tulane, and then he went on the river and joined the Longshoremen’s Union. He did that until he passed in 1968. I attended schools in the neighborhood—Phyllis Wheatley Elementary, Bell Middle School, and Clark Senior High.

Jarrett: Ada is older than me. She is around the same age as my brother. I was the last child in my family, and we had more money by the time I was going through school, so I graduated from Cabrini. Ada’s father and my family are from the same hometown. I was born in Pointe Coupee Parish on False River—that’s where her family was from.

Ada: My grandmother come off the Parish, in New Roads; they were all mixed with Indians. My dad, my grandmother and them spoke Creole. All very fluent. They spoke it very well—especially when us kids were in the room—but I never picked it up.

Jarrett: My mother spoke Creole fluently and so did her sister. But you have to remember, it was an embarrassment to speak Creole because that spoke to the fact that maybe you weren’t as educated. When we moved here to New Orleans, my mother was a little bit ashamed of it because she was highly educated. We lived on North Miro Street between St. Ann and Dumaine, around the corner from Ada. We had a neighbor, Mr. Rene Grandjean, who was from Derval, France, and he married into the Divouplait family, who were descended from free people of color. They lived at 927 North Miro. He spoke French, my mother spoke Creole, and so they would always speak.

Ada: They could understand each other.

Jarrett: They spoke it amongst themselves when they would have Sunday coffee. We had two important Black-owned restaurants within a block of each other. Ms. Chase’s restaurant was on one corner, and we had Willie Mae’s around the other corner.

My mother was Director of Head Start in Desire Housing Development; she worked for Model Cities. She was an educator in the time of the Black Panthers. And at that time, Tootie Montana, his son Darryl Montana, and the rest of their family lived in the Desire Project. My mother befriended Tootie’s wife, Ms. Joyce, and all them, and that’s how she started sewing, beading, and sticking feathers. My father was friends with Mr. Arthur Vigne, who was in the Jolly Bunch, and we sewed to make his baskets. Everybody put in and helped for parade day. At that time, second lines were mostly men. Women didn’t really participate much in the second lines, but my family had me dress up and walk down the street after the second line with little cute clothes that matched the parade. I was like, “Okay, I like this!”

Ada: The Jolly Bunch was a famous group for a long time. They come off of St. Ann and Broad Street—that used to be the meeting ground.

Jarrett: The second lines passed by on Orleans Avenue, and once a year Tamborine and Fan’s Super Sunday parade would too. Jerome Smith was tutorage to all of us. We all looked up to him. My brother, Quinn, worked for Housing Authority and he used to pick up trash in the Lafitte Project. Jerome mentored him, telling them about being a part of the neighborhood and how to be a man, until he finished school.

The Money Wasters

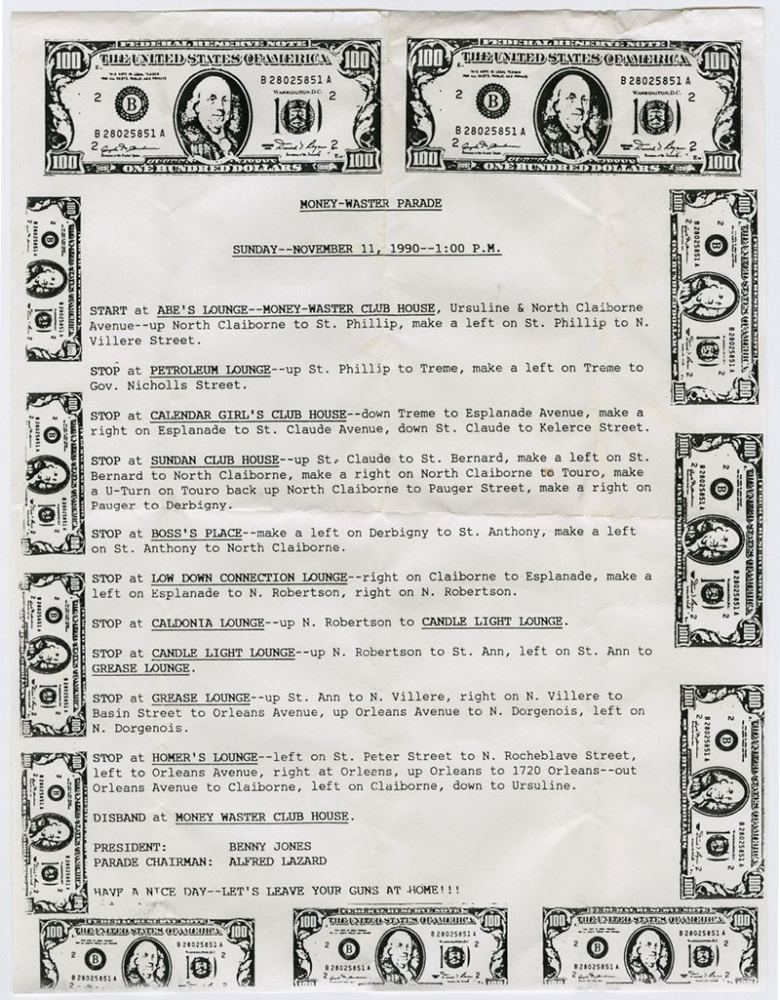

Jarrett: There was an original Money Wasters group from the Sixth Ward, which was founded in 1920. That group went on forever and ever. Some of the members in that club included Mr. Louis Charbonnet, his brother, and Dorothy Mae Taylor, who was a city councilwoman. At some point, the club unraveled. In April of 1976, the Money Wasters was rejuvenated with another group of people.

Ada: Lois, do you remember some of the original members?

Lois Nelson: Benny Jones Sr. was the president. My brother Chris, Rudy…Uncle Peter Frank, Jimmy Brown. Anthony Bennet came a couple of years later.

Jarrett: You got a good memory. Now, second line clubs always had the women as queens, but then the Money Wasters made a division of women.

Lois: I’ll tell you what Doc, in the late 1970s, women couldn’t parade on the street—they had to ride on the car. The first two years the men Money Wasters paraded, we all went to their second line, and we all danced on the street. We decided to go to their meeting on Derbigny and St. Phillip and told the men we wanted to parade with them. They told us—I’m not disrespecting you now, Doc—they said, “If you welfare bitches could come up with a band, then y’all could parade.” [Laughter]

Jarrett: That’s right!

Lois: And we got that!

Jarrett: Have a supper; whatever! Right!

Lois: We was the first women to hit the street.

Jarrett: What happened? Y’all had fun?

Lois: We had a ball. We paraded almost every year, but one year, we missed. We told the men, “We coming back.” We went by Cohen’s Formal Wear on North Claiborne and got the tuxedos with the men’s shoes. At the same time, people down in Gentilly was making our other outfits. Anthony Bennet knew because he made all of our stuff, but my brother and the other Money Wasters didn’t know. When we came out, people were saying, “Them sad bitches, they raggedy. They had to go get tuxedos and all that.” But that wasn’t our game. We didn’t worry about that. When we hit Governor Nicholls and Marais, we told Anthony, “Now we going to change.” It looked like we were arguing with him because we all just broke out and run. While we’re running, we’re coming out them tuxedos.

When we get on Esplanade and Marais, Lady Buckjumpers was in there with all our clothes. Each one of their members had each one of our clothes together, so whoever had your clothes was the one who was dressing you. One side of our outfit was yellow. The back of our outfit was red. Our shirt was yellow. We had on Red Wing shoes from Imperial. Our hat was yellow.

When we come out, the limousine driver was waiting for us. Now, we needed some more money to give to the limousine driver, but we ain’t got it. The man felt sorry for us, and said, “You know what? I’m gonna bring y’all where y’all got to go.” We drank Dom Perignon champagne until we hit Columbus and Claiborne where we met up with the club and the band again. When I stuck my feet out of that limousine, there were rhinestones on my shoes. Let me tell you, everybody went to hollering and screaming. You know what my brother told me? “Y’all some dirty bitches!” That parade was what made everybody start changing clothes.

After Katrina: Joining the Money Wasters

Ada: For many years, the president of our club was Nelson Thompson, who was my brother-in-law. Nelson hung it together for the longest until he passed. He and his brother Cornell “Peanuckle” Thompson were young when they joined the Money Wasters, and Nelson was familiar with parading because he had masked with the White Eagles since he was 10 years old. From the time he joined the Money Wasters, the only time Nelson didn’t parade was the two years after Katrina.

Jarrett: When I was a little girl, the White Eagles came out of the Tonti Court of the Lafitte Projects. Nelson lived there with his first wife, Violetta, off of St. Ann and North Dorgenois. They moved, and we kind of lost him. I didn’t reunite with Nelson until after Katrina when he rented a house from me. We started realizing that he knew Quinn and my family, and that I was that little girl from a long time ago. All the history started coming back. Nelson started masking with Congo Nation with Donald Harrison Jr. The first masked my daughter and I masked Indian was with Donald under Congo Nation and Nelson.

Ada: For two years after Katrina, Nelson begged me to come parade because I followed them. My son is 44, and I followed them for all those years—walking. Nelson told me, “C’mon sister-in-law, you ain’t doing nothing! You need to lose some weight. Get your fat ass out there on the street.” You couldn’t say no to him. I hit the street for the very first time in 2007 when Nelson brought the club back. I’ve been hitting the street ever since.

Jarrett: That year, I was Ms. Money Wasters. Right afterwards, Nelson told me, “Now you going to have to be a member.”

Ada: Nelson did all of our designs.

Jarrett: He did everything.

Ada: He could go from start to finish—from cutting out the wood to stapling the feathers. He did it all.

Jarrett: And then Nelson taught a lot of people.

Ada: Taught a lot of people coming up in that world— uptown and downtown—how to do it.

New Generation

Jarrett: Our goal to remain a true, traditional second line group, with the court on cars. We have not tried to make it more like a Mardi Gras parade with big floats. We have little handmade floats, things like that. We try to make it affordable for people. A lot of people really want to do this, but it’s a commitment.

Ada: As opposed to being out there, trying to sell stuff to raise money, we set a price for the money we need to parade. We buy our own clothes, and we pay our parade taxes. By April the 15th all your money and funds are due cause by then, we have to start paying police and everybody.

Kasey: I look forward to having the meeting. If you wanna show up and show out, we have to present the money. Everything’s been positive.

Jarrett: Yeah, we’re a stress-free club.

Ada: Definitely.

Jarrett: Before and after every meeting, we pray. With a rise in gun violence at the second lines, which is not part of the culture, it’s really important that we remain a cohesive group, and take precautions.

Ada: We have one club, DAM—Dignified Achievable Men—that we’ve allowed to parade with us since they weren’t able to get their own date, but that’s all. We don’t see them until it gets time to talk or negotiate.

Jarrett: The father of the young man, Dismus, who runs DAM, was in the Big Seven Social and Pleasure Club—

Ada: Yeah, out the St. Bernard Project—

Jarrett: He broke off from his dad and formed DAM. They paraded with us twice as a second division.

Ada: After the mass shooting at the Big Seven parade on Mother’s Day, I took care of one of the people, Deborah Cotton, who was shot, at the hospital.

Jarrett: Deborah formed a relationship with the guy who shot her.

Kasey: Wow.

Jarrett: Yeah, she did. She wanted to forgive him and find out who he was. That’s like the worst thing that I could ever remember happening at a second line. And the crazy thing is that our second line was a few weeks later. We weren’t too far behind them.

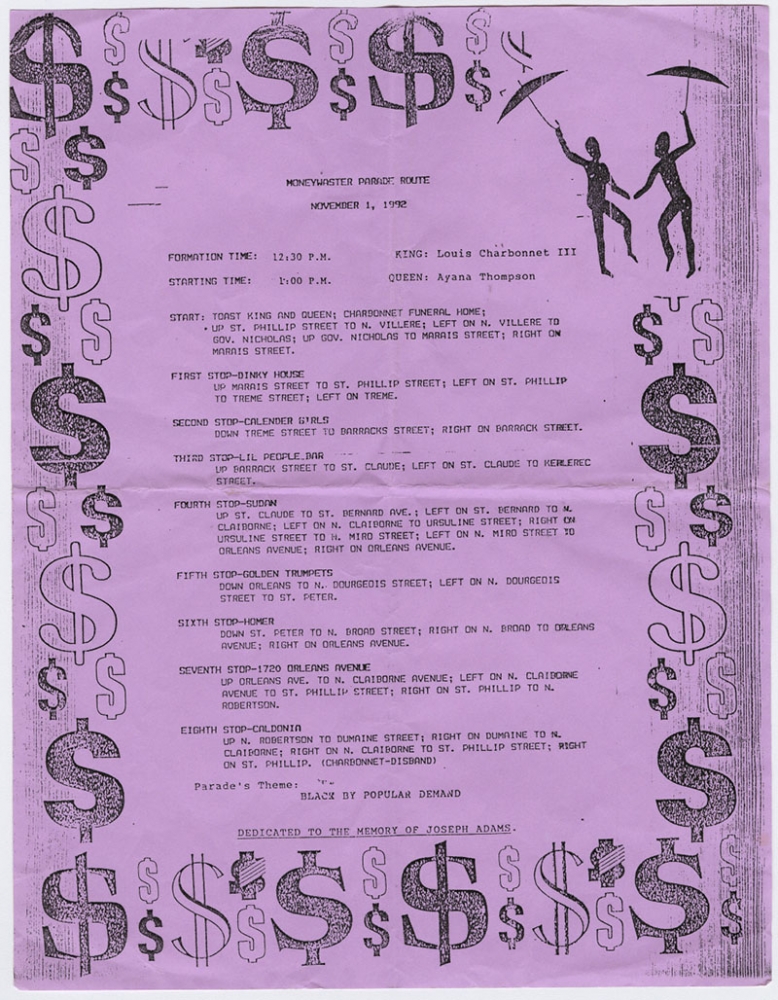

We used to start our parade by the Charbonnet Funeral Home on St. Phillip and North Claiborne, but we moved to the Treme Center on North Villere a few years ago. We go up Villere to Orleans, Orleans to Broad, and we have a few stops along the way. My office, Primary Eye Care, on North Broad in the Seventh Ward, is our main stop.

Ada: Our favorite stop.

Jarrett: We stop here the longest. It’s a historic building that used to be the office of Dr. Henry Mitchell, the first Black optometrist in the state of Louisiana. He examined Martin Luther King here in 1961. Dr. Mitchell died one week shy of his 90th birthday in 2007. He worked here up until Katrina, and then I took over the building, renovated it, and moved in. It’s now on the National Register of Historic Places.

From Primary Eye Care, we go to St. Bernard, take a right and stop around N. Miro at Seal’s Class Act, go to Claiborne, take a right, and end up by Kermit’s on Columbus and Claiborne before disbanding at North Robertson and St. Philip, which is Tuba Fats Square next to the Candlelight Lounge.

Since Nelson died, Dimetrius “Punchy” White does a lot of the work for our second lines. But Nelson, again, that’s tutorage. He wanted to teach you. It’s what I’m doing with my daughter, and with Kasey, who works with me at Primary Eye Care. You know, this is a contagious type of thing. I said to Kasey, “We really need young people to take an interest in the culture.”

Ada: She got the bug.

Jarrett: Kasey’s whole family’s from the Seventh Ward. Her daddy’s side had a family bar.

Kasey: Bassinet Bar off Pauger and Galvez. It was a neighborhood bar, but it closed after Katrina. My grandparents lived for second line music, and they really had the footwork. When Dr. Johnson asked me to participate, “Would you like to see what it’s about?” I was like, “Oh, great.” But the first-time parading, it was like, “Wow. This is what I’ve been missing out on. I love it.”

Ada: It’s the best experience in the world when you come out that door. Kasey threw down for it.

Kasey: Only thing, one year…

Jarrett: She lost her toenails!

Kasey: I danced so much my toenails came off. Afterwards, I was thinking, “Oh, this is just bruised.” No, they’re gone!

Ada: I got my great-grandson, Tahj Robertson, involved in second lines now. He was two years old when he came out and he did a fantastic job. I thought the music might scare him, but he was looking at the instruments, and kept trying to touch everything. During the second line I asked him, “You tired?”

“Leave me alone, I’m good.”

He was walking and dancing with his fan, doing his little thing. I thought, “Oh my God, thank you. A new generation.” Some man gave him ten dollars, and said, “Here bra, you working it! I love it!”

He did not stop walking until we got to St. Bernard and Roman Street and then all of a sudden, he said, “Maw-Maw, pick me up.” His dad picked him up and after that he went boom. Passed out! Yes, he did. Now, when he sees the pictures of the parades, he says, “We second lining Maw-Maw?”

Kasey: Baby Wasters.