I was born in 1956. I grew up downtown in what they call the Seventh Ward on North Robertson between St. Bernard and Annette. Back in the day people would say, “by Circle Food Store.” As kids in the 1960s and early ‘70s, if they’d have a second line, we tried to find where the parade was. If we couldn’t find it, all we had to do was find Jerome Smith. He would be going that way, and we followed him. At the parades, we were introduced to different social and pleasure clubs’ styles—the hats, the polyester or 100% cotton pants, the silk shirt, the gator or the smooth leather shoes, the leather suspenders and belts. And most importantly, the accessories. Their accessories made it glow. A basket, fan, or umbrella in his hand is what made your eyes buck, what made you ball up your toes: “Who made that!? Man, look at what he got in his hand! Look at that streamer he has on.”

Steamers was made with two or three colors. The basket was made of cardboard, canvas, coat hanger, silk material, plastic flowers, and what Indians use on their suits—marabou. Those materials matched your pants and your shoes. When the person who’s carrying it hears you say, “Who made that?” his feet go to moving, his eyes get wide, and he just flaunts it. Coming up as a little boy, going to see that was a beautiful Sunday.

When you go to the second line, you’re going to meet people in the neighborhood—people that you know, people that you don’t know, new friends, old friends, even a little enemy. But you didn’t have the violent part. Before the “I’m’a catch him at the second line” started, parades used to be almost anywhere from six to eight hours. If you get out early that morning, strike up that band—pay that band the right money—they would bring you all the way Uptown and all the way back. If you saw somebody you didn’t like, you put your beer to mouth, and kept going. After six days of hard work, you were there to enjoy yourself. Now we only get four hours. Right now, it’s 2020, and we’re still in that phase of, “I’m hoping Joe Blow don’t see Lil Randy and decide to take care his business.” He’s not just hurting Randy, he’s hurting a lot of other people, because now you’re taking our day from us.

Tamborine and Fan

Jerome “Big Duck” Smith was a freedom fighter who walked with Dr. King. He was one of the co-founders of Tamborine and Fan. If you learned the history of Big Duck, as a man he was real, real cool. As a teacher, he was hard. As a motivator, even harder. When he said, “Bo-bo-bo-bo” that meant you were in trouble; something he asked you to do, you didn’t do. I don’t want to put him in one spot. He might have started on Pauger and Robertson in the Seventh Ward, but he had kids slowly coming to him from around the city. If you came, you were welcome.

Tamborine and Fan had what they called “the Building,” where you learned your life lessons. Many times, Big Duck made everybody go to the building for class. We read books, and there was a certain chant that we did. In that chant, Jerome asked you so many questions, and you had to respond to him:

What is dope?

Dope is poison and death.

Everybody comes to a fork in the road. Tamborine and Fan tried to prepare you for that. And you might ask, “What that fork is?” Between going straight, and being a good person, or going to the left, and trying out what the streets is calling you for. And when I say, “the streets calling,” that could be anything from drug dealing and using, to prostitution or murder.

That chant goes a long way. Right now, if I were to go to the state penitentiary, and I’m scared—I don’t trust nobody, don’t know nobody—I could say, “Class!” And somebody would answer: “Downtown, Seventh Ward, New Orleans, 504.” I know that person was part of Tamborine and Fan; he remembers what came before that fork in the road. He’s going to come to me, we’re going to start talking. Myself, I’m a good all-around person, but I got caught up in that fork in the road myself years later. I slipped, but through Tamborine and Fan, Jerome Smith gave me a foundation. I was able to snap back. It was a hell of an experience.

Jerome Smith also helped the elderly that was in the neighborhood whose lights might about to be cut off, rent or medicine needed to be paid. But the children was his love. He would teach his best to try to make you straight and strong. Right now, when it comes down to being a man, I stand on his shoulders. The shoulders that he stands on are men like Dr. King. I can’t call that. Jerome’s not my dad, but he took on the image of my dad.

From age five to 14, if you played ball with Tamborine and Fan, he’d reward you by sponsoring you in the Bucketmen’s second line. You didn’t have to be a great athlete—just come to the day camp. From five to nine, all you’re supposed to do is come to play ball. Now mind you, the oddest thing about Tamborine and Fan is that your coach might be only a few years older than you. Collins “Coach” Lewis was just four or five years older than me! I’m thinking he’s a man. He’s still in high school! When I was 16, I started coaching 8 and 9 years old. Now the eight years old looking up to me like I’m a hero; like I’m an adult: “That’s my coach!” That’s what helped make the bond with everybody because that coach is thinking, “That’s my child. I love him like a daddy, not like a little brother.” Because, you know, your brother can beat you up.

As you got older, you would go to a two-story house with beautiful trees in the yard that was located in the Eighth Ward between Marigny and Mandeville on North Claiborne. In that building, you would have reading, math, and history classes with second line, jazz, and gospel music playing. Once we finished with our studying, we learned how to make accessories for parades with cardboard—cut it out, put it together with Elmer’s glue. Or you would learn how to mask Indian: take cardboard, canvas, and beads.

They had a brother called Melvin Reed, the master, and they made you watch him, and he’d show you pointers. Put five different colors together, and make it seems like it’s one big pretty color. He passed that on to—not me, because I’m colorblind—but to Sudan members David Crowden, Adrian “Coach Teedy” Gaddies, Kendrick Johnson, and to many more kids that grew up to parade. Jerome Smith also had Gerald Emile, who got a lot of old folks in him—his grandparents and mama made sure he knew his prayers—and he taught them to the little kids at the day camp and on the Hunter’s Field. I was one of them.

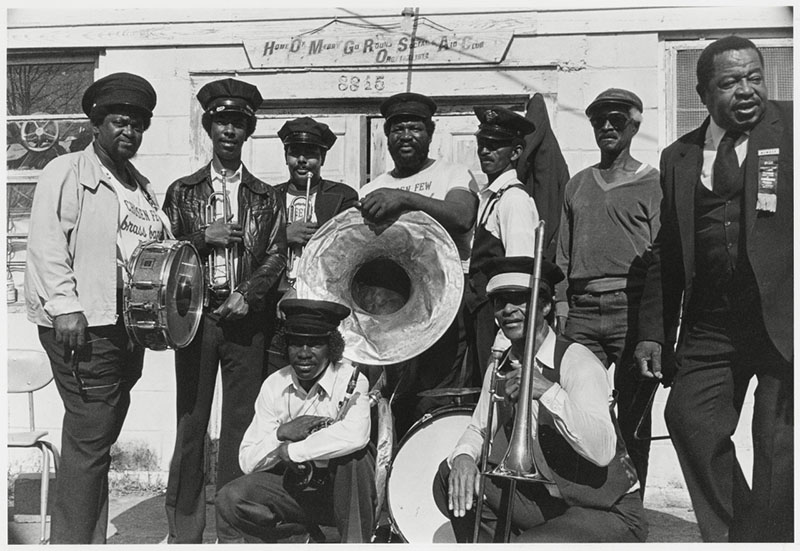

For the Bucketmen parade, they had the Olympia, the Tuxedos, and the Pin Stripe brass bands. As I got older, more bands started popping up. They had so many people playing music in New Orleans. They just had a lot of talent. In your middle and senior high school, those band teachers really taught you how to play. We had rhythm. We made you snap your fingers and slide your feet. The way the snare and bass drum was playing was more like church music. I remember Jenell “Chi-Lite” Marshall—he’s got two kids in the parade with us now—created a beat that was a little faster to where you didn’t slide, you chopped.

When I dance, I don’t dance to the whole band. I pick an instrument off each song, and I dance to that instrument. My best tuba player was Anthony “Tuba Fat” Lacen. Now, was he the best of the best of the best? To me, yeah, because of the way he kept a beat. He didn’t just blow it hard; it was like he had a bird coming out of it. The way I danced to him, he made me vibrate. Tuba was so sweet he’d make you look so nice no matter what you were doing. That’s how come we wound up making him the Grand Marshal of Sudan for 2003.

Starting Sudan

I started Sudan with brothers who were part of Tambourine and Fan. As we got started, we called ourselves a committee: John Dobard, David Crowden, Adrian “ Coach Teedy” Gaddies, Kenneth Dykes, Archie Chapman, and myself. I brought that name to the club. We didn’t want our name to make it seem as though we were better than nobody. One day, I’m in the library, and I was looking at a Black history book, and I saw the word Sudan. It explained that there was a tradition there where men went from village-to-village dancing for peace. I said, “Damn, I’m taking this to the club!” We had meetings at each other’s houses every other Monday. We met on the porch of Archie Chapman’s family on Ursulines Street. His grandmother accepted anybody who walked through the front of that door. Ms. Rose is a beautiful woman.

David, Teedy, and Terrance Allen are mainly the decorators of our accessories. They could do it all. Myself, no. They said they didn’t even want me putting glue on the cardboard because I put too much glue and when you put the canvas down on it, it bleeds through and makes the canvas look dark. They say if I make a circle, when I cut it out, it’s a square. When they are working, I make sure I’m there and that I’ve got people laughing and joking. Melvin Reed has shown them how to make the decorations stiff because when you’re dancing, you sure don’t want your stuff falling apart. And if it does fall apart, there’s a response for that: Keep going. But Sudan does not break up their things. Nor do we tear our clothes off. We try our best to come in the same way we went out.

In August of 1983, we christened our banner at St. Augustine Catholic Church in Tremé. We wore black and white tuxedos, and Father Jerome Ledoux prayed over us and our banner. As we came out the door, we gave out roses and had a two-hour parade through our neighborhood. In 1984, we got a parade day on the second Sunday in November, and that’s been our date ever since. Ain’t changed. We begin at the Treme Community Center by saying a good prayer. I’m asking God to stop everything that’s not right. To stop it and let us have a peaceful day.

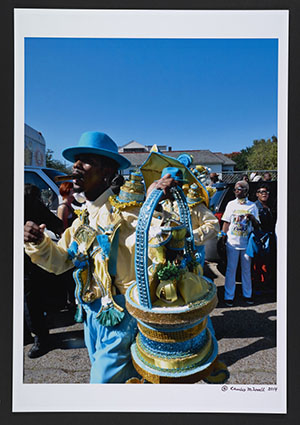

If you notice in some sanctified churches, when the spirit hits the congregation, they jump up, and the preacher holler, “Let it go! Let it go!” You start moving your feet, shaking your head, and wiggling your shoulder and bouncing your hips all over. That dancing is a spirit releaser. Coming out the door is similar—it’s like letting the spirit go. When I come out the door, I like to see them white clouds in the air because when I’m dancing with them white clouds, I like to think everybody in heaven smiling. No, I’m not the best dancer. No, I ain’t got all the moves. But it’s something about me with them eyes and the lip hanging, the hat crooked, and my hands over my head. I’m cutting loose; I’m letting out the spirit.

For years, our parade went through the side streets of our neighborhood. A lot of old folks said, “Boy, we can’t come on Claiborne Avenue and see y’all parade. I guess we’ll see you when we see you.”

“No, we gonna pass that way. Come on, be outside on the porch.”

When we passed by, sometimes they had water for us. Kenneth Dykes’s grandmother used to give us sandwiches. My grandmother was on North Robertson Street. David Crowden’s grandmother was on St. Ann’s Street. And on Pauger and Robertson Street, everybody knew that’s where Big Duck started Tamborine and Fan’s Building. Jerome has come to every parade since we’ve been in existence. The first one to see just how we doing. The second one was to see how we looked, and how many members we had. The third one was to see, “Oh, okay, y’all still doing it.” And after that, he’s like, “That’s my children.”

In 1985, we had done came out the Treme Center. We’re in the Seventh Ward, going down Pauger Street between Marais and Urquhart. The First Division just turned the corner, and a fight broke out on the right-hand side of the street. I see the fight. I jump out the parade, run to the two brothers and say, “Oh no! Not on this day. We not even gonna have that!” The crowd helped me to break up that argument. Another brother near the fight grabbed one, somebody else grabbed the other. In the name of Jesus, we haven’t had no serious problems in our parade, but we have had a tragedy with one of our members.

Archie Chapman’s Funeral

The week after our third parade, one of our club member’s sisters died. On November 15, 1986, we went to an old school church for her wake. The preacher was going off, saying some beautiful things, and Archie whispered to us, “Man, if something happen to me, please don’t let the preacher talk this long over me!” We all started giggling, not to be too loud.

Afterwards, we went to a little bar and poolhall called Sam’s on Rampart Street right around the Melpomene Project. We ate, had a good time. Archie brought me home in a little Volkswagen. He pulled up at my house. Had to be near about eleven o’clock. My old lady hollered out the window, like if I was a child, “Bernard! Bring your ass inside!” Archie thought that was real, real funny: “Boy, look how your wife hate on you!!”

I said, “All right bra, I’m going inside. You just make sure you be all right.”

“I gotta go DJ at the Spades,” which was on St. Philip and North Claiborne. I said, “All right bra, holla at me in the morning.”

Later that night, Archie was sitting under the Claiborne bridge, talking to a friend. A young brother walked up to him and stuck a gun in his face. I guess he said, “Give it up.” The little lady who was with him said they would give up what they had.

The dude looked at a chain Archie had on his neck and said, “Give me that, too.” Soon as Archie reached around his neck to get it, dude shot him point blank.

The next morning, I’m in the Seventh Ward. I got my little, little son with me. We were going to get a haircut. Somebody stopped me: “Bernard, Bernard, you hear what happened?”

I said, “No. What’s happening? Talk to me.”

“Man, Archie got killed last night.”

I pulled over on Annette and Villere and jump out the car, go into the store, and call his mama. She told me, “Yeah, that was Archie.” Archie was our club’s first death. We was hurting. We was real, real, real hurt. We stopped under the bridge by Charbonnet Funeral Home on St. Philip. When you’re second lining downtown, if you ever pass under the I-10, there’s something about hearing that music. It bounces back into you. And that’s where we stopped at. And when I told you we put it down for him, we put it down.

For Archie’s funeral, we brought our Ferris wheel baskets out with us. We placed Archie’s basket on top of the hearse, bent down in the place where he was killed, and Gerald Emile led us in a song he taught us on Hunter’s Field, the same song we sung before we come out for our parade:

If my mother don’t go, Lord, I’m gonna journey right on.

Well, I done signed up, made up in my mind. Lord, I’m going to journey right on.

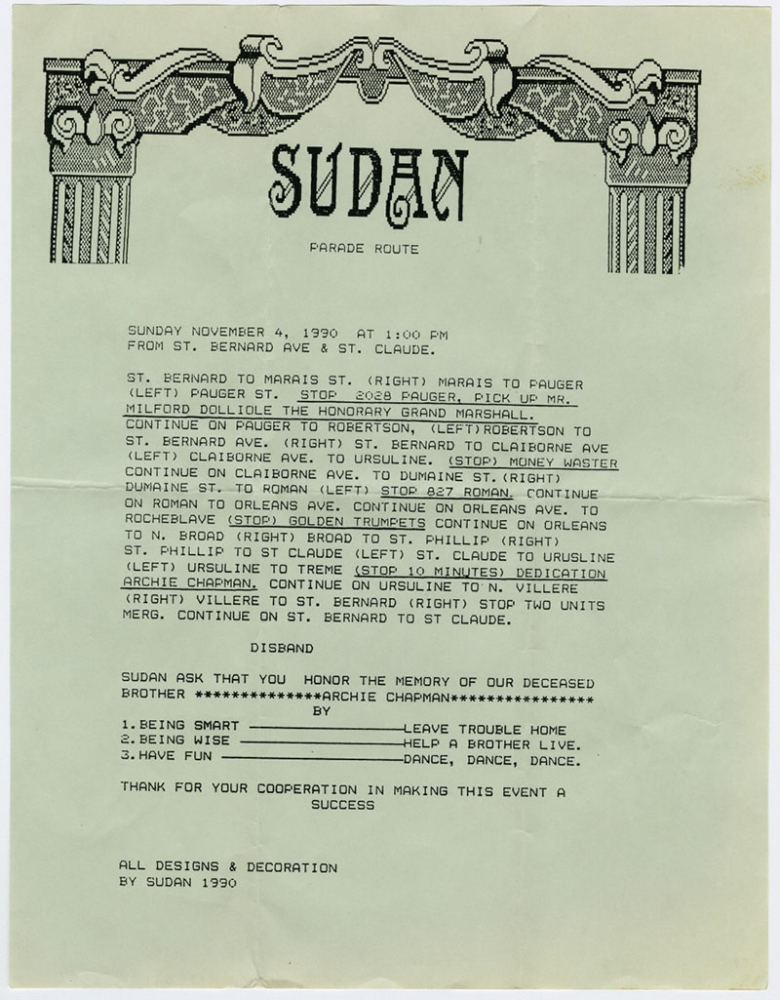

The man who killed Archie, John Brooks, was only 21. He killed eight people in New Orleans between August and December of 1986, and was charged for other robberies and rapes. We have honored Archie on our parade route every year since then. We stop by Ms. Rose’s house on Ursulines Street in Tremé to pay our respects to her, and to remember our friend.

In the Sixth Ward by, the Money Wasters used to have a building right across the street from Charbonnet Funeral Home, and they hosted a stop for us. Our seamstress, Ms. Annie, lived on 827 Roman. Beautiful old lady. She took care of us like we was her children. She would make the pants, the shirts—anything we could think of. We could go to her at the last minute, yeah.

The Golden Trumpets was a nice little division that was a bunch of older men on Orleans between Tonti and Rocheblave. We’ve outlived them now. When we first began, the Golden Trumpets called us the “Baby Stroller Parade” because we always had our kids in our parade. David and I had newborns, and we said, “Our babies gonna roll today.” We got that from Jerome Smith and his last son, Taju. When Jerome paraded, he decorated the stroller, put Taju in the same clothes he had on, and pushed him through the parade. I thought that was so, so sweet, myself. I copied off of him. When we come down Orleans Street, we have about four strollers in the parade. Two in the First Division, two in the back.

We always keep a stop for Archie at his grandmother, Ms. Rose’s, house. We paid tribute to his memory on her porch. Most likely we broke up at a barroom on St. Bernard and St. Claude called Sidney Brown’s.”

Slide Your Feet and Choppin: Brass Band Music

In Sudan, we don’t select our members by dudes who got real smooth feet. All we do is look at him in his eyes. He could be so awkward to where when you look at him, you lose the beat. But, with Sudan, we figure out a way to dance around him to where everybody’s saying, “Man, them boys get down.” Our parade has two divisions. The third year that we paraded, we hired New Birth to play for our first division. We came up together in Tamborine and Fan. They still play for us. They done got real good, so sometimes they be busy on our day. But, when we can get them, yes, they play for us. They are our number one band. We brought them up, they brought us out.

David Crowden, Adrian Gaddies, myself, and a bunch of other little brothers are getting older; we’re in our late 50s and 60s. We definitely want to hear more “Fly Away” than “Let’s Go Get ‘Em.” Why? Because in four hours, trying to keep up with the band, you can really blow yourself out, lose a lot of sweat, and cause yourself to cramp up. Talking about drinking pickle juice and orange and all that? Man, too late! If your body ain’t got prepared for the day, no matter what you take, it’s not going to stop that charley horse from getting to you. You can’t enjoy your day if your leg is cramping. Matter of fact, if your leg locks up, you really want to go home because you ain’t doing nothing but dragging your leg. And people want to know, “Why you ain’t dancing!?” And you be wanting to say, “I am hurting. I actually got charley horse.” Really, you want to say something crazy, but them people just want to see you dance because they know you.

If you give me a little smooth beat, I can go longer in parading. You’re working your hips, and your back, and you’re moving your head a certain way. I make better faces like that when I’m dancing. I could “duck roll,” I could fall on the ground and nobody ain’t going to walk over me, or step on me, because they running. But if you do that, and they running, the band liable to run over you because they’re moving fast.

The Second Division is the hot-footers. They used to have Rebirth but since they aren’t on the street that much anymore, they pay for bands like Hot 8, TBC or the Big 6. They’re thinking about how their peers from other clubs are seeing them on the street, and they want the crowd. If you watch us come out the door, you could see it. A lot of people come out the door fast, fast, fast. I call it “choppin it up” when they moving fast. And then here I come out the door, I’m like a turtle. I got a big smile. I’m trying to spread the spirit of happiness: “Man, dance with me! Rock with me! Slide your feet with me! Catch your square and stay there.” Chris Terro from the Big 6 is in our club, and we are hoping he will lead the club to the next century. We always try to talk to him about church music because he helps select a lot of the music the Big 6 plays.

All that music is like a round table. Comes round, and round, and round, like a circle. Slow the music down. It might help us with these angry attitudes that some of us be having. Because we need all the help and prayers we can get for our youth. Nowadays, they just don’t care where they’re at. They will try to hurt someone who done did them something. Half the time, the person that they’re hurting ain’t done nothing more than took a few hundred dollars from them. If they let that go, they’re going to get more—five times more than what they lost that little dude took from them. We just got that anger built in, and we need to find the keys to unlock it.

Building Community Strength

Right after Katrina we came out calling ourselves “Shocking the World.” We didn’t come out in no expensive clothes. We came out in overalls as carpenters to rebuild New Orleans. Our baskets, fans, and our umbrellas was the shit.

I think about where the strength of our club has gone all of these years. When we first began, a retired police officer, Jake “Daddy Jake” Johnson joined the club with these young brothers in their 20s. He enjoyed being with us; never tried to over-speak or overrule us. Always said, “Okay, let me hear it. What we doing? Sounds good. Let’s do it.” He was part of another social and pleasure club that didn’t second line called the Fishermen. They met at a barroom on St. Bernard Street between Urquhart and Marais. These men was hard workers, real good people. They was in existence for maybe fifty years. Daddy Jake told us for as long as the Fishermen had been in existence, they didn’t have a building. They always had to depend on somebody else’s space.

In all the years we’ve been second lining we’ve never said, “Let’s skip this year’s parade. Let’s put that money in the bank to buy a building. Let’s get us a raggedy double under Sudan’s name– everybody who put up money got a share in it.” If you decide you want to leave, we’ve got to figure out a way to buy your share. Or you just leave your share sitting. In the 1980s, I kid you not, the houses in the city were real cheap. Nobody wanted to even come down here in this swamp, and many of the light complexion people in the Seventh Ward was trying to get to Slidell and St. Tammany Parish. Some of the old Black folks owned houses, but their children didn’t live around there anymore, and weren’t helping them take care of it.

Now, gentrification is real. The same houses are worth a lot of money. You ought to see what they’re doing in the Seventh Ward. They flipping them houses. In one of the blocks that we love to go in, my partner Dykes’ block— God bless the dead—they had some houses that people sold for $30-40,000, and the people done came and fixed the house up. Now the house is on the market for $240,000. We don’t know as many of the people on the back streets we used to visit.

Although we don’t have a building, our parade continues to grow through our inspiration and connections to Tamborine and Fan. For years, myself and Kenneth Dykes was over the kid division.

Before Dykes died, he was able to talk to one of our other members, Kendrick Johnson, who worked at St. Augustine High School for a while, and said, “Please help Bernard out.” Did Bernard need help? You’re goddamn right. It is beautiful to have the kids with us but dealing with the parents of the kids is not always an easy job. Where I would say, “Hold up. Take your money, and let the doorknob hit you where the good Lord split you,” Kendrick Johnson would say, “Hold up. I’m gonna show you on paper where your money is going. Sit down, Mama, or Daddy, let me get you a cup of water, so you can understand.” Book-keeping-wise, Kendrick is on top.

Kenneth Dykes’ niece, Cheryl Ann Roberts, is one of the children of Tamborine and Fan. She ran track, was one of the cheerleaders, and later a teacher with the Tamborine and Fan Day Camp. We also demonstrated together at City Hall to demand a park in our neighborhood. When Cheryl Ann said that she was going to start the Versatile Ladies of Style, we welcomed her club with open arms.

About four years ago, another brother with Tamborine and Fan, Tyrone “Pie” Stevenson, asked us about a new club, Spirits 2 Da Street, joining our parade. Pie grew up masking with Big Chief Allison “Tootie” Montana and the Yellow Pocahontas and used to play ball in school with us. Mr. Dolliole, who played with the Olympia Brass Band and was one of Sudan’s first grand marshals, is his uncle. Pie has his own Indian gang, the Monogram Hunters, and when his friend Larry Terrance wanted to start their own second line club, he asked us if they could join us.

Due to the fact we wanted to make the parade a little bigger, we said yeah. Now, mind you, that club is only a division. When you come to Sudan, we’ll allow you to parade with us, but you cannot have an upright banner because the second week in November is Sudan’s day, but you are welcome to take part of it. You can have that long banner that runs across the street. We have other stipulations: no trolleys, no large floats. We ain’t back there trying to police you, but try your best not to smoke weed in the parade. Both clubs agreed to our little stipulations and we’ve been having a beautiful relationship with them ever since. They add a beauty to our club because they try to do some beautiful things. Together, we are saying, “Let’s enjoy this day. Let’s thank the Lord that we are alive.”

Interview conducted by Rachel Breunlin and Bruce "Sunpie" Barnes of the Neighborhood Story Project.