Watch as THNOC’s Eli Haddow and Eric Seiferth discuss the hollowed-out cypress log that once served as a city water pipe.

A month ago, we wrote an article about THNOC’s acquisition of an iron pipe long buried beneath Bourbon Street. It quickly became the most popular story we have posted, so we thought our readers might enjoy hearing about another recently acquired piece of antiquated infrastructure—an original city water pipe made out of cypress wood. That’s right: wood.

This cypress pipe, installed circa 1820, was recently acquired by The Historic New Orleans Collection. (Photographs by Eli A. Haddow)

The “new” old pipe, which is to say our most recent tubular acquisition, was part of a waterworks system envisioned by architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe. Latrobe had previously worked as the architect of the US Capitol building in Washington, DC, and was behind the nation’s first modern waterworks system, in Philadelphia.

New Orleans was among the larger cities in North America when the US purchased Louisiana in 1803, making it an ideal candidate for a modern amenity such as water delivery. It was also a city undergoing great change, with Anglo-American migrants from the north and east settling in the modern Central Business District and immigrants from St. Domingue (modern-day Haiti), both black and white, fleeing the Haitian revolution via Cuba. New Orleans’s population exploded in the early 19th century as the city expanded beyond the colonial bounds of the French Quarter.

Maps from 1803 (left) and 1825 (right) show how New Orleans expanded in the first quarter of the 19th century. The French Quarter is outlined in red for comparison. (THNOC, 1987.65 I;The L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection at THNOC, 1946.2)

Latrobe was given the contract to complete and operate the waterworks in 1811 and sent his son, Henry, to work on the project, but war with Britain the following year delayed construction. Once construction started in earnest, Latrobe chose a durable, moisture-resistant building material to construct his pipes: cypress. At the time, cypress logs were among the most prevalent natural resources in the city’s low-lying environs, which today would encompass the neighborhoods of Broadmoor, Gentilly, and Lakeview, among others.

Latrobe’s system fed water from the Mississippi River into a steam-driven pump that was located at the intersection of present-day Decatur and Ursulines Streets. From there it entered the network of hollowed-out logs and was used primarily to flush the streets of refuse and fight fire.

“We’ve got all kinds of human waste, animal waste,” said Curator/Historian Eric Seiferth, detailing the substances that could have been swept away. “There’s a fish market, a vegetable market . . . so by having this water to spray down, you could get some of that muck off the city’s streets.”

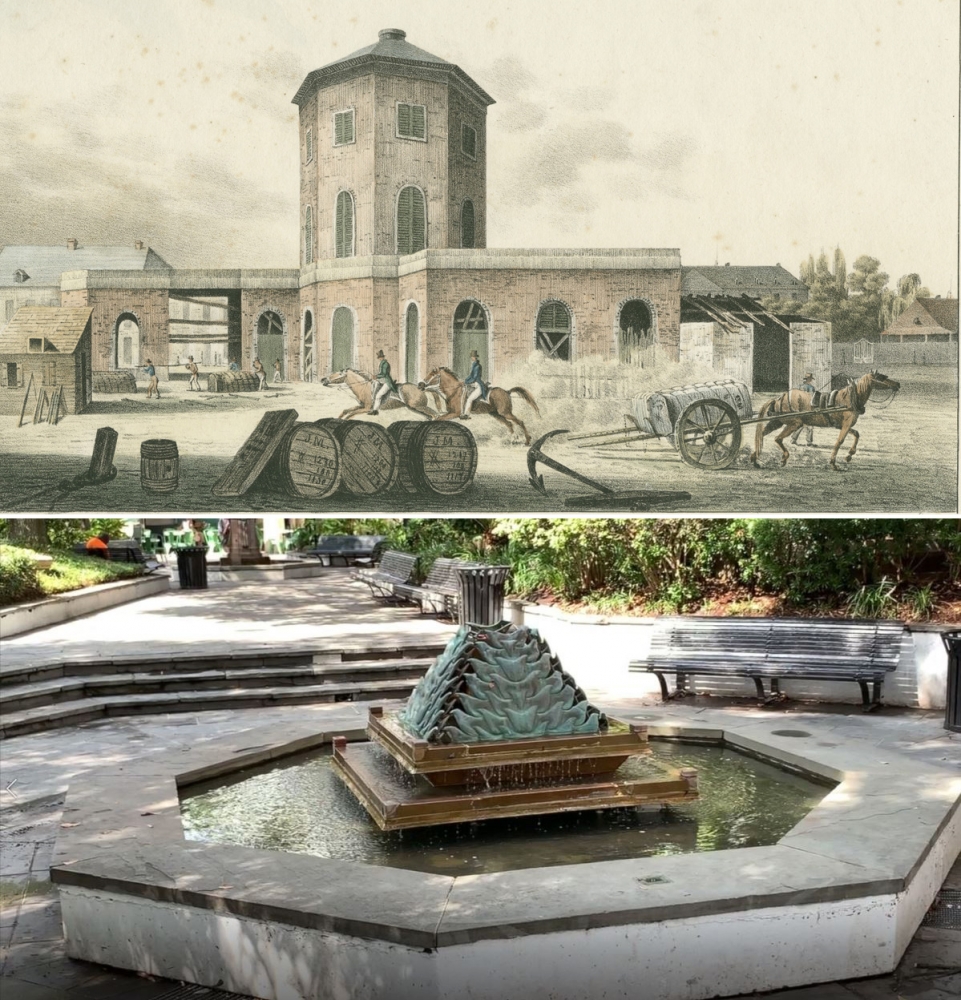

A circa 1821 drawing of Latrobe’s pump house (above). The site is home, today, to Latrobe Park, where the fountains echo the octagonal design of the original building (below). (THNOC, The L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1937.2.5; photograph by Eli A. Haddow)

As we noted in our story about the Bourbon Street pipe, refuse from the French Quarter sometimes ended up flooding the homes of residents in the lower-lying “back of town”—the area across Rampart Street that now includes the Tremé neighborhood. Unfortunately, misery for back-of-town residents was proof that the system was actually working according to design.

Latrobe never saw his design come to fruition. In September 1820, he died of yellow fever while working on the intake pipe that would draw water from the river. Tragically, his son Henry had succumbed to the same disease three years earlier.

The city took over and finished the project, but problems abounded. The hollowed-out logs were prone to rot in the New Orleans heat and humidity, according to historian Carolyn Kolb. They also clogged with sediment from the unfiltered Mississippi River water. Even before the system was fully complete, city authorities went on pipe-buying trips to the east coast to secure metal hardware for the city’s waterworks.

The city supervised the system until 1836, when it handed control to the Commercial Bank of New Orleans, a private enterprise in which the city purchased a stake. The Commercial Bank, which controlled the city’s water supply until 1869, went about completely replacing the wooden system with cast iron pipes. The Bank built a new water intake pump and reservoir in the Lower Garden District, rendering Latrobe’s French Quarter pump house obsolete.

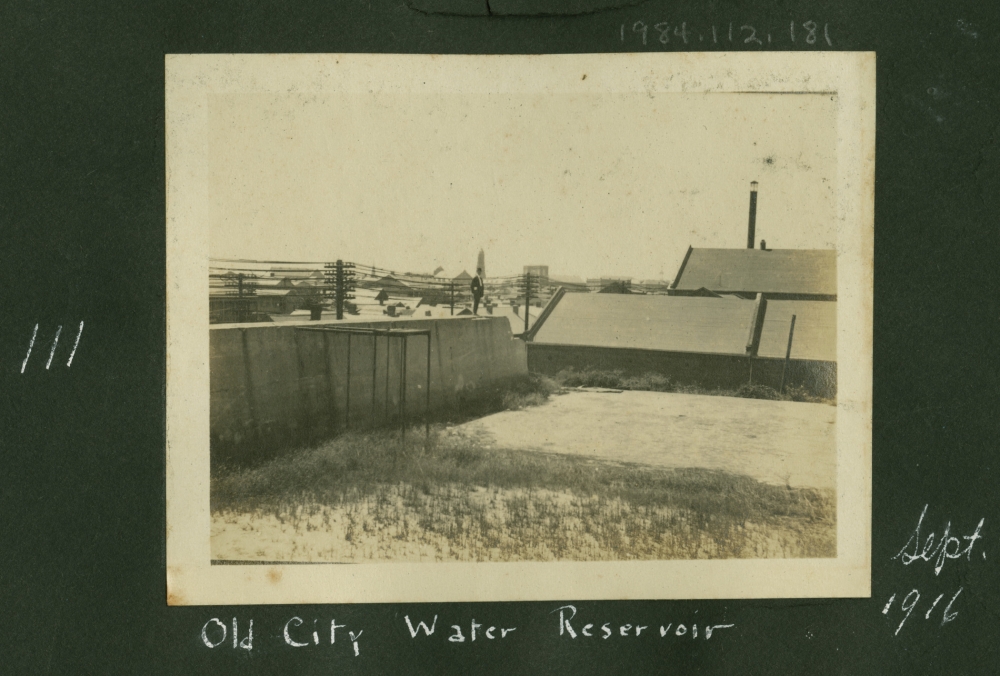

A 1916 photograph shows the reservoir originally built by the Commercial Bank of New Orleans in what we now call the Lower Garden District. It was replaced in the early 20th century by the Sewerage and Water Board’s current waterworks in Carrollton. (THNOC, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Peter Bernard, 1984.112.181)

By the time our Bourbon Street water pipe was installed, sometime between 1875 and 1886, the New Orleans Waterworks Company had taken over the monopoly and installed more iron pipes. The original cypress logs, now 60 years old, were either removed or left beneath the streets of the French Quarter.

But as chance would have it, city archaeologist Mike Godzinski reached out to us in late August and asked if THNOC would be interested in acquiring a section of wooden pipe sitting in an office at City Hall. No one knew how it got there or when it was unearthed—but as a newly minted infrastructure nerd, Seiferth couldn’t pass it up.

At City Hall, Seiferth points to the iron sleeve that could have joined this section of cypress pipe to another section. (Photograph by Eli A. Haddow)

“I’m excited to have this pipe because I think people are going to be interested to see how water delivery began in New Orleans,” he said. “This will be a great complement to our cast iron pipe from beneath Bourbon Street. It’s part of the first effort we can point to that capitalized on the water of the area for civic use.”

Thanks to our highly professional Collections and Preparation teams—they’re the ones who physically move and account for items in the museum’s holdings—the fragile pipe is now safely in THNOC's care, ready to tell the story of Latrobe’s waterworks.

Chris Deris (left) and Joe Shores (center) secure the pipe for transport from City Hall to The Historic New Orleans Collection, while Seiferth (right) stands guard. (Photograph by Eli A. Haddow)

“New Orleanians care deeply about infrastructure,” said Seiferth. “As long as we’re talking about what does and does not work with our pipes and pumps, it’s essential to know how those conversations started.”

Two hundred years after Latrobe laid the groundwork of this history, one thing is for certain: these conversations aren’t likely to stop.