It’s been quite the year at The Historic New Orleans Collection. To commemorate the city’s tricentennial, we did our best to present three centuries of history in just 12 months of exhibitions, publications, and programming. Looking back, 14 THNOC staff members highlight moments, discoveries, and innovations that stood out this year, some routine and others that could only have happened in 2018.

1. Views of North Claiborne before the overpass

A 1947 image shows N. Claiborne Avenue at Ursuline Street, prior to the construction of the I-10 overpass. (The Charles L. Franck Studio Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1979.325.5136)

This photo of Claiborne Avenue in 1947 was shot before the construction of the Interstate 10 overpass. Here we see how wide open, green, and beautiful the neutral ground there used to be. Currently, there is a lot of attention being paid to the myriad ways the overpass negatively impacted the surrounding African American neighborhoods. This view of the street before the construction really helps bring home the scope of our collective loss.

—Becky Smith, head of reader services

2. A striking painting from New Orleans, the Founding Era

Théodore Gudin's 1844 painting Expédition de La Salle à la Louisiane, 1684 is a romantic depiction of La Salle's fateful final voyage. (Image courtesy of the Musée national des châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon, Versailles, France)

The exhibition New Orleans, the Founding Era was my favorite program that we put on this year—it certainly captured my attention. It was so well done by all involved and so well organized that I can still “walk through” the galleries in my mind. If I had to choose a favorite piece in the exhibition, it would be the painting of LaSalle’s landing at Matagorda Bay. Yes, it is a romanticized view, but the color and light sparked the imagination and drew viewers in. As an interpreter, the show-stopping quality of the piece allowed me to engage visitors and explain the real history behind the painting.

—Cecilia Hock, interpretation assistant

3. Rare ad from opening night at the French Opera House

The French Opera House was a center of social and cultural life from its opening in 1859 to its burning in 1919. The left and right images show an advertisement from the building's opening night before and after conservation. (Left and right: THNOC, 86-2165-RL; center: THNOC, The L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1939.5)

I came across one item that I found really fascinating: a broadside advertising a December 1, 1859, performance of the opera Guillaume Tell (William Tell). Head Registrar Jennifer Ghabrial brought it to my attention because it was one of a number of items that needed a quick examination before going out for conservation. When we examine an item, we note wearing through time, such as discoloration, brittleness, ripped book spines or paper, and soiling that could be fixed by a conservator in order to prolong its life and make it suitable for careful handling for researchers and exhibitions. In this instance, the Guillaume Tell broadside had been printed on inexpensive and very acidic paper, leaving it discolored, brittle, and with possible pest damage, causing chipping to the edges and holes throughout. Our head librarian, Pamela Arceneaux, was out that day so I stepped in, otherwise I might have missed the chance to see it. I discovered that December 1, 1859, was the opening night of the legendary French Opera House! The other interesting aspect of this item is the great conservation work that was done on it. The conservators were able to repair the chips and holes, likely with an organic adhesive and non-acidic paper that was matched to the color of the broadside, making it stronger while still keeping the integrity of the piece. I feel really fortunate to work in an institution whose mission is to preserve, catalog, and conserve important artifacts that bring the history of New Orleans alive for researchers.

—Nina Bozak, library cataloger

4. The Liberty Bell comes to New Orleans

The Liberty Bell travelled to New Orleans for the 1884 World's Fair, where it was heralded as a symbol of post–Civil War unity between North and South. (THNOC, 1982.127.140)

While looking through the catalog one day for a specific image of a train, I found something unexpected. It was a photograph of a peculiar train car with the Liberty Bell mounted on top, surrounded by guards. Painted on the flat car were the words “Philadelphia” and “New Orleans” with clasped hands in between. I never knew that the Liberty Bell had travelled here for the 1884 World’s Fair. Sure enough, it was brought here as a symbol of post–Civil War unity between North and South, and upon looking into it further, I found that its journey—and the fair itself—was a very complicated story involving Reconstruction, race relations, and the shifting political landscape in the South during that time. I plan on investigating the bell’s journey fully in an article this upcoming year.

—Eli A. Haddow, marketing assistant

5. More than meets the eye

A painting depicting the fire at the Saint Charles Hotel conceals a previous work made on the same canvas. (THNOC, 1992.156)

Think this is just a painting of a burning hotel? Look closer! The unknown artist grabbed a handy canvas—originally a military portrait—and ran out to capture the mayhem of the infamous fire at the St. Charles Hotel in 1851. What looks like scaffolding in the bottom right may actually be the braid on the uniform. And, what appears to be a military cross for heroism comes through as well (circle). Now, focus on the toppling dome. At the edge of the black, you will see the red and gold braid of the uniform’s lapel (square). This phenomenon is called pentimento, the emergence of an underlying work through a new painting.

—Malinda Blevins, interpretation assistant

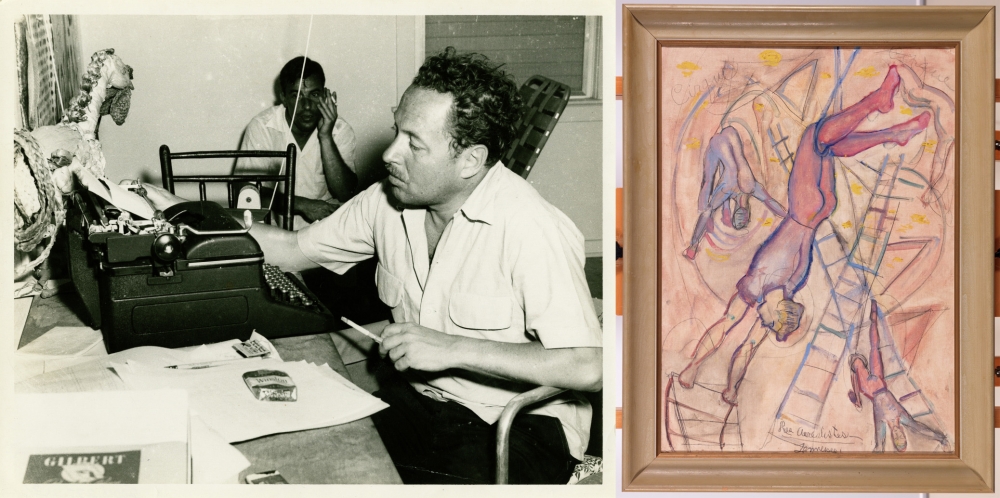

6. Tennessee Williams, the painter

(Left) Tennessee Williams works at his typewriter. Not many people know that the playwright also painted. (Right) Les Aerealistes is the only Williams painting in THNOC's holdings. (THNOC, The Fred W. Todd Tennessee Williams Collection, 2004.0277.2; THNOC, 2012.0221.1)

I’ve spent some time studying Tennessee Williams’s paintings this year for the Tennessee Williams Annual Review. Not everyone knows he painted. Indeed, he wasn’t technically very good, and his work can be a little adolescent, but what the pictures lack in technical ability, they often make up for in theme and interest factor: namely, their relation to his life, his work, and the works of others. Every time I look at our one painting of his, Les Aerealistes, I keep seeing new references, and I now find it hypnotic. It is a web of Williams’s interests and personal and textual allusions. Among other things, Les Aerealistes references the 1956 film The Trapeze, whose love triangle among Tony Curtis, Gina Lollobrigida, and Burt Lancaster—who starred in the film adaptation of Williams’s The Rose Tattoo and was himself a trapeze performer in younger years—has a decidedly homoerotic element.

—Margit Longbrake, senior editor

7. Past employees at the Williams Residence

(Left) Gardener Frank Fujii—who was born in the United States—was hired by THNOC founder Kemper Williams less than a year after he was released from a WWII internment camp. (Right) Fujii maintained the grounds of the Williamses' home in Santa Barbara, California. (THNOC, The L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 79-78-L.6)

Researching the lives of the people who worked for THNOC's founders, General L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams, moved me this year. Finding notes about the cooks, maids, butler, and chauffeur in General Williams’s papers showed me the strong personal connections between employer and employees, while also revealing long working hours and wage disparity based on gender and race. I did a deep dive into the history of Japanese internment camps to learn more about Frank Fujii, the gardener at the Williamses’ Santa Barbara home. Although Fujii was born in the United States, his parents were from Japan, so his whole family was sent to the Gila River Relocation Center in Arizona. Fujii likely learned his gardening skills in the camp, where gardening was one of the few outlets for internees to express their culture. General Williams hired him to maintain his Santa Barbara property less than a year after he was released from the internment camp.

—Lydia Blackmore, decorative arts curator

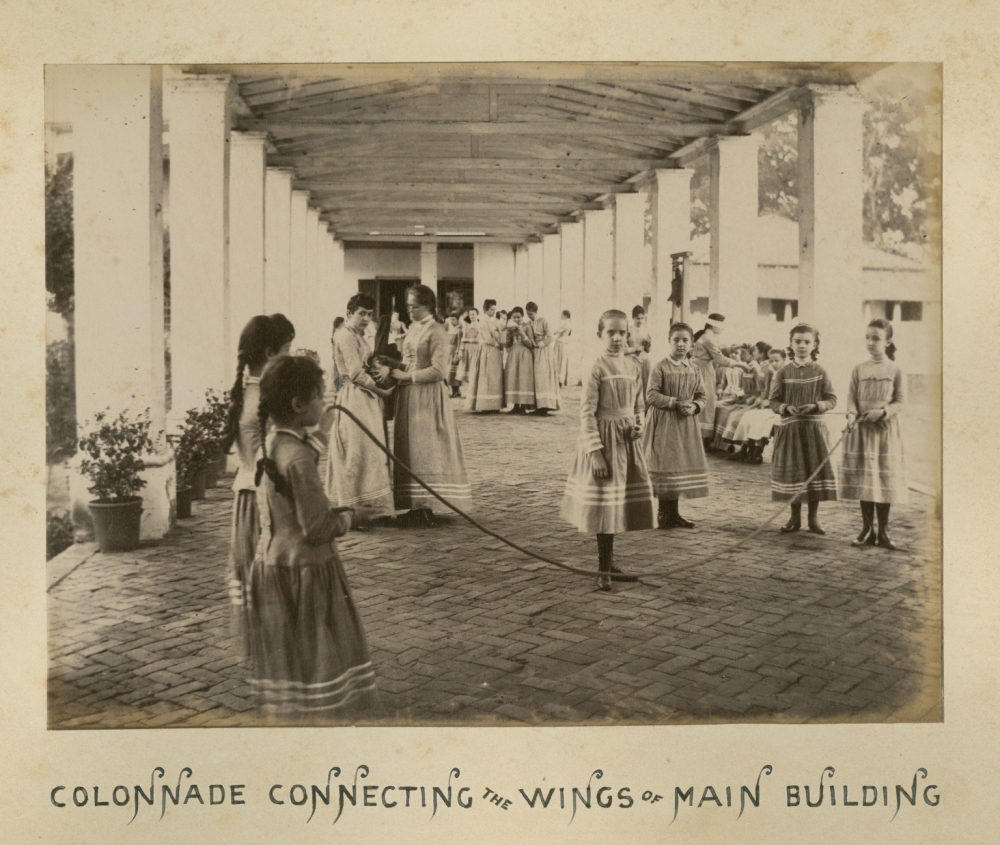

8. Photographs from the Ursuline Convent

An image from an album of photographs show girls playing at the old Ursuline Convent in the Lower 9th Ward. (THNOC, 2018.0242)

The Historic New Orleans Collection recently acquired a photograph album titled “Views of the Ursuline Convent, By One of the Sisters, 1894.” The album contains 37 6x8 albumen prints that show the sisters and students going about their daily lives at the Ursuline Convent when it was located on Dauphine Street in the Ninth Ward (1824–1912). The photographs were taken by Mother St. Croix, who lived in the convent between 1888 and 1904. Mother St. Croix was a pioneer, if not the first, female photographer in Louisiana. She was certainly the first woman photographer to systematically document life in New Orleans, albeit within the confines of a cloistered community. See more of the images here.

—Jude Solomon, curator

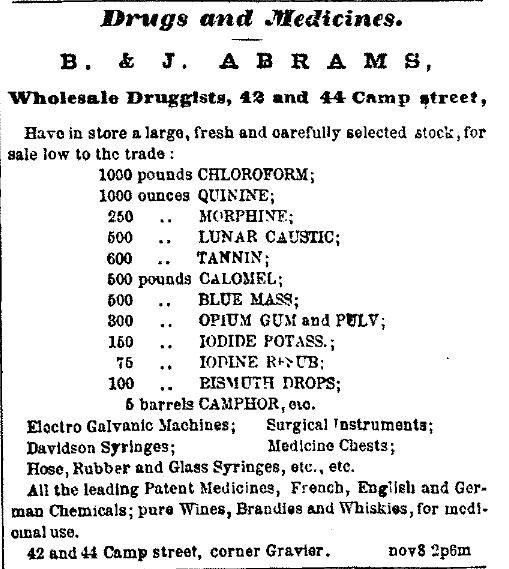

9. Newspaper ad for STD cures

Pharmacists' ads in the 19th century promised cures for sexually transmitted diseases, though they did not perform as promised.

I was fascinated by this pharmacist’s ad from the October 13, 1863, issue of The Era, an old New Orleans newspaper. “Blue mass” was a mercury-based medicine used to treat syphilis. Nineteenth-century newspapers were full of ads from doctors and pharmacists, assuring readers that their cures for STDs were swift and effective. If your curiosity is piqued, and you want to learn more about these miraculous mercury cures, here’s a spoiler alert: they did not perform as promised.

—Cathe Mizell-Nelson, editor

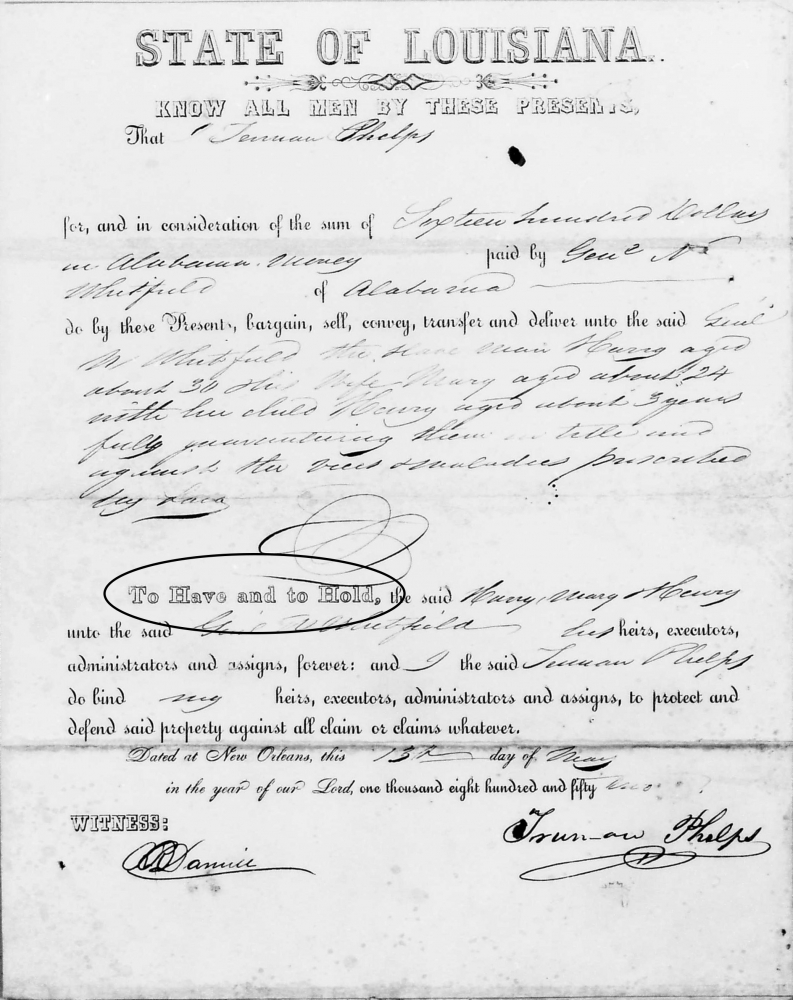

10. Echoes of the New Orleans slave trade

The Gaineswood house in Demopolis, Alabama was home to General Nathan Whitfield and his enslaved laborers before the Civil War. (Image courtesy of the Classical Institute of the South)

As the curator and research coordinator for THNOC’s Classical Institute of the South, I travel with two fellows each summer to catalog objects in private collections in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama. General Nathan Whitfield’s home, Gaineswood, in Demopolis, Alabama, was one of our stops this year—and investigating the general’s papers in the Auburn University special collections led to some sobering information about his life as a slaveowner. Whitfield’s receipts and correspondence were full of details like buying “negro clothing” in bulk from Mobile wholesalers, or hiring slave catchers to track down runaways. But nothing drove home the harsh reality that he enslaved other people like finding a group of notarized receipts from New Orleans slave sales. Gen. Whitfield spent three days here in May 1852, spending thousands of dollars buying human beings. This likely happened just blocks from my Royal Street office. Most chilling was how the notarial forms described Whitfield’s ownership as “to have and to hold,” twisting the language around both slavery and marriage (emphasized, right).

As the curator and research coordinator for THNOC’s Classical Institute of the South, I travel with two fellows each summer to catalog objects in private collections in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama. General Nathan Whitfield’s home, Gaineswood, in Demopolis, Alabama, was one of our stops this year—and investigating the general’s papers in the Auburn University special collections led to some sobering information about his life as a slaveowner. Whitfield’s receipts and correspondence were full of details like buying “negro clothing” in bulk from Mobile wholesalers, or hiring slave catchers to track down runaways. But nothing drove home the harsh reality that he enslaved other people like finding a group of notarized receipts from New Orleans slave sales. Gen. Whitfield spent three days here in May 1852, spending thousands of dollars buying human beings. This likely happened just blocks from my Royal Street office. Most chilling was how the notarial forms described Whitfield’s ownership as “to have and to hold,” twisting the language around both slavery and marriage (emphasized, right).

—Sarah Duggan, coordinator, Classical Institute of the South, and research curator

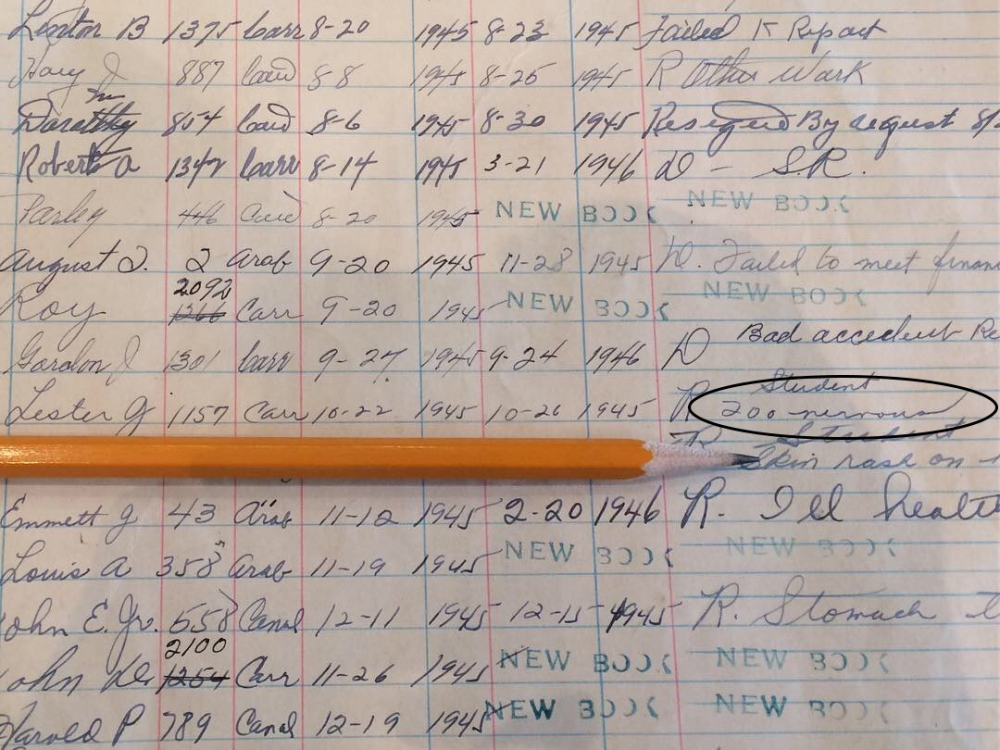

11. Employee log for streetcar drivers

A 1945 NOPSI ledger book lists the reasons that employees were let go. (THNOC, gift of Mr. Stephen J. Stegemeyer, 2010.0255.410)

I stumbled upon a ledger from New Orleans Public Service Incorporated (NOPSI), which administered utilities and public transportation in the city during the 20th century. I pulled it out to identify the date for a motorman’s badge that might be going on display in THNOC’s new exhibition center. The badge belonged to a man named Lester J. Bonano who was fired in 1945 after four days on the job. The cause for his termination was listed as being “too nervous” to drive a streetcar. As a streetcar commuter, I know that a good streetcar driver is an aggressive streetcar driver. If your driver is too nervous to ring his bell at cars that block the tracks, your ride will take forever. This find proves that bold and daring have been valued personality traits for streetcar drivers for over 70 years.

—Emily Perkins, curatorial cataloger

12. Working on the Tricentennial events

In March, THNOC hosted a block party to celebrate the tricentennial symposium "Making New Orleans Home."

At the start of 2018, I became involved with the New Orleans Tricentennial Commission’s Cultural and Historical Committee to help with logistics for the “Making New Orleans Home” citywide symposium. I helped coordinate hotel accommodations for speakers, the event venue at the Monteleone Hotel, AV accommodations at four separate locations, and a block party on Royal Street following the first full day of sessions. I had the amazing opportunity to work closely with one of the most organized, high energy, competent women on our staff, Elizabeth Ogden Janke. It was a joy and a pleasure. She worked the people side of logistics, while I worked the technical side, but we coordinated together. And I heard one of our neighbors on Royal Street comment, during the block party, that they “never knew The Collection could be so much fun.”

—Kathy Slimp, manager of administrative services

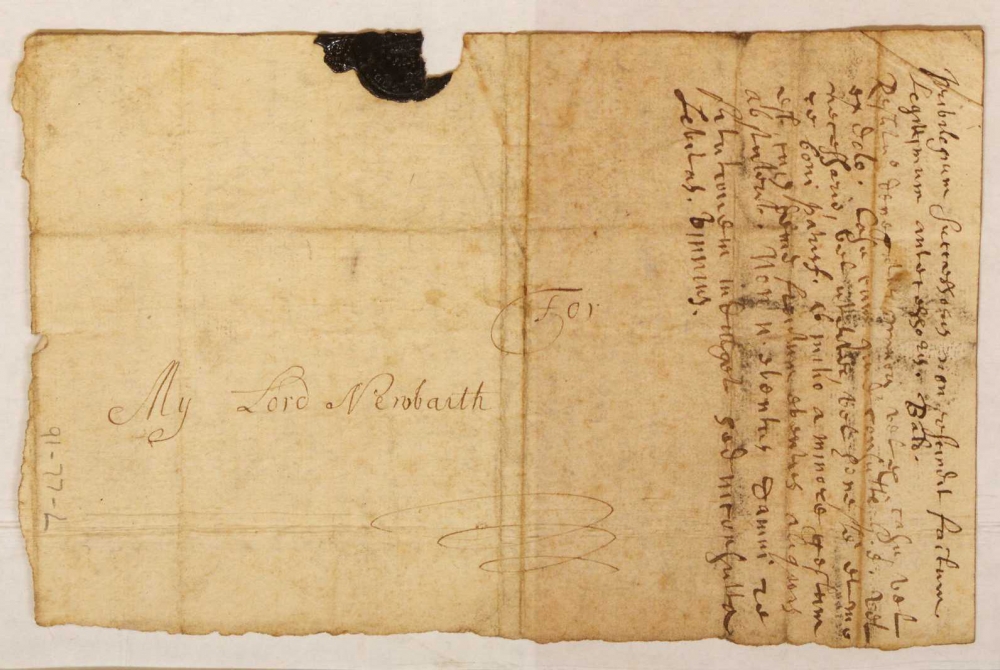

13. Strange document in Latin

A document, probably from the late 1600s, is written in Latin, and we aren't sure why. (THNOC, 91-77-L)

While processing a new manuscript collection, the Edward Alexander Parsons papers, I came across a manuscript that is nearly illegible and written mostly in Latin. Its presence in that collection is a mystery. The only clue I could work with was the English phrase “For My Lord Newbaith.” My online inquiries revealed that it might relate to John Baird, Lord Newbyth (an alternate spelling). He was a Scottish advocate, judge, politician, and diplomat who lived from 1620 to 1698. In 1664 he was named an ordinary lord of session—a Scottish judicial appointment, not a lordship in the popular sense of the word. The title would have died with him, which would suggest this odd paper dates between 1664 and 1698.

—Michael Redmann, manuscripts cataloger

14. One system to coordinate them all

Attendees watch a panel discussion on the UpStairs Lounge Fire in June. THNOC's new guest management system allows visitors to register online for programs and exhibitions.

Attendees watch a panel discussion on the UpStairs Lounge Fire in June. THNOC's new guest management system allows visitors to register online for programs and exhibitions.

Throughout 2018, staff in the development, marketing, museum programs, technology, and visitor services departments worked closely together to implement a new software system, Tessitura, that has radically changed how THNOC manages ticketing, online registration, gift and membership processing, and linking these to marketing appeals. After just six months in a complex new system, these departments have learned so much about each other’s processes and workflows that now, through discussion and collaboration, we’ve made great improvements to our interdepartmental collaborations. Implementation of systems—whether it’s a matter of replacing an old system or, as in the case of ticketing, going from no system to one sophisticated enough to be used by the Met Opera—can be downright terrifying. The collegiality of our Tessitura team and the widespread commitment to improving THNOC via new technology has made this monumental task a success.

—Lindsey Barnes, database manager, and Lori Boyer, head of visitor services

Thank you for reflecting on 2018 with us, and be sure to continue to follow THNOC in 2019. We are sure it will be another banner year, for THNOC, New Orleans, and our visitors. For daily updates and highlights from our work, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.