As a member of THNOC’s marketing department, it’s often my job to wrangle our vast collection of more than one million artifacts into social media posts that run about 100 words. One such effort was our #Manuscripted series, where we extracted quotations from our collection of personal letters, journals, and oral histories—artifacts that can only be found at THNOC.

While perusing the words of 19th-century visitors to New Orleans, it struck me that many of their concerns are still relevant today—and some could fit right into an online comment thread or bitter social media post. I’ve found that certain phenomena are perennially associated with “The City that Care Forgot”: the reputation for illicit entertainment, the tendency to party instead of work, and the similarities with a certain European counterpart.

1. Who are you calling immoral?

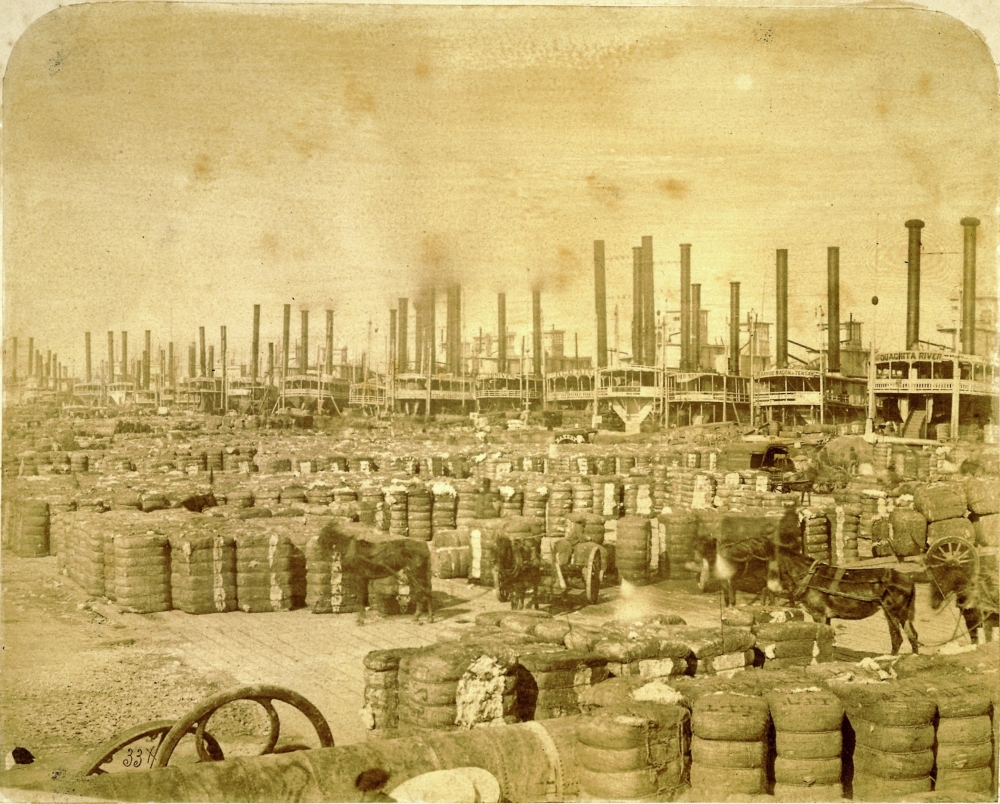

Commodities stacked at the port of New Orleans are valued more than piety, according to Samuel Gray. (THNOC, 1982.238 i-xxxiv)

The quote: “As to the morals of the city, I think that vital piety is a commodity less sought after than cotton, flour, pork, sugar, and molasses. The natives impute the dissipation of the city to Northern people, but until the Creoles can set a better example, they should be careful how they charge it upon them.”

The writer: Samuel Gray, a traveler in the city, possibly from Boston; January 1, 1848.

Let’s drag this quote right out of context and into the 21st century, where tourism has surpassed commerce as an economic driver. It’s almost impossible to draw a direct parallel here because the very immorality that Gray denounces in his letter is the basis for the hard-partying reputation that’s responsible, in large part, for drawing 10 million tourists each year to the Crescent City. Would it make sense, today, to say that “vital piety is a commodity less sought after than sales tax revenues, hotel bookings, and conventioneers”? Maybe. Despite its deep Catholic roots, the city has a long history of salacious marketing, most notably with the aggressive promotion of Storyville—its legal red-light district—to wealthy white men at the turn of the 20th century.

Vintage footage shows Bourbon Street during the mid 20th century. Many locals blame Bourbon's reputation on out-of-towners, but let's be honest with ourselves. (THNOC, gift of Paul Werner, 2016.0142.24)

The other side of Gray’s quote is the blame factor: he criticizes locals—whom he refers to as Creoles, possibly distinguishing between French-speaking citizens and newly arrived Anglo-Americans—for dodging responsibility. One thing has changed here: many New Orleanians today proudly own the city’s partying reputation, and point to liberties such as go-cups, 24-hour bars, and that "do-what-you-wanna" attitude to distinguish their city from, say, Cleveland. But I wouldn’t say that blaming outsiders is gone completely. Taken to their extreme, these lax alcohol laws and New Orleans’s laissez-faire lifestyle have given us Bourbon Street, which the New York Times recently called: “perhaps the country’s pre-eminent 24-hour street party.”

That seems like something locals would want to own, but instead, Bourbon is dismissed as a tourist trap teeming with college kids, conventioneers, and depending on the news of the day, criminals. As Tulane University Geographer Richard Campanella wrote in his history of the street: “Educated newcomers and sophisticated visitors figure out quickly that declaring disdain for Bourbon Street is the first step toward showcasing their taste and gaining insider status.” Maybe it’s the strip joints, the smell, or the surge of bars blaring cover bands that leave a bad taste, but Bourbon embodies the qualities that set New Orleans apart, and if locals have a problem with it, they could do something other than blame everyone else. At least, that’s what Samuel Gray might say.

2. But what do you mean by "real" work?

Mardi Gras is billed as the “biggest free show on earth,” but is throwing parties all New Orleans is good at? (THNOC, gift of Boyd Cruise, 1959.2.320)

The quote: “…everything has been very orderly and the police have taken care for once of the Drunken men, the day has been a success, by far the finest Show ever seen here even in Antebellum times, what a pity that they have not the same energy for real work that they display in getting up amusements…”

The writer: An unnamed husband writing home to his wife outside of New Orleans on Mardi Gras 1872.

The writer of this letter gives a colorful account of Mardi Gras in 1872, which was coincidentally the first time that Rex mounted a parade. He describes “the incessant noise and din,” “a huge host of rascally newsboys,” and the King of Carnival “dressed as a Turkish Sultan” followed by a cavalcade and “innumerable pedestrians.” He is, overall, impressed by the festivities, less so by the city’s ability to do anything else correctly. This is another comment that is somewhat complicated when put in today’s context. What does he mean by “real work”? New Orleans’s ability to “get up amusements” has created a thriving local industry, which has to count for something, although the current debate as to the sustainability of an industry that largely relies on low-paying jobs is worth continued exploration. Or, could the writer be talking about something more basic, like functioning infrastructure? Eh, there we may have an even bigger issue.

Irish Channel residents may have been unsettled by the emergence of this giant snake from a pothole in their street. Luckily, it was just a resident making fun of one of the city's most notorious problems. (Photo by Nick Weldon)

The “basics” are what New Orleans struggles with the most. Keeping rainwater out of people’s homes and cars, and keeping people’s homes and cars out of holes, is a difficult task here. But when problems arise, locals are likely to respond with (what else?) amusement. Who can forget Sinkhole de Mayo, which sarcastically celebrated the appearance of a massive fissure in Canal Street? Or how about the kayaker who, as buildings around him flooded in August 2017, steered his watercraft to the bar for a quick beer? (Never mind the reaction to a recent high-profile robbery case) Today’s New Orleanians have a penchant for manufacturing silver linings around the city’s shortcomings—boil water advisory after boil water advisory—even as they grit their teeth with frustration. While it's probably safe to say that these antics may frustrate our letter writer, we can safely say that he wouldn't be surprised.

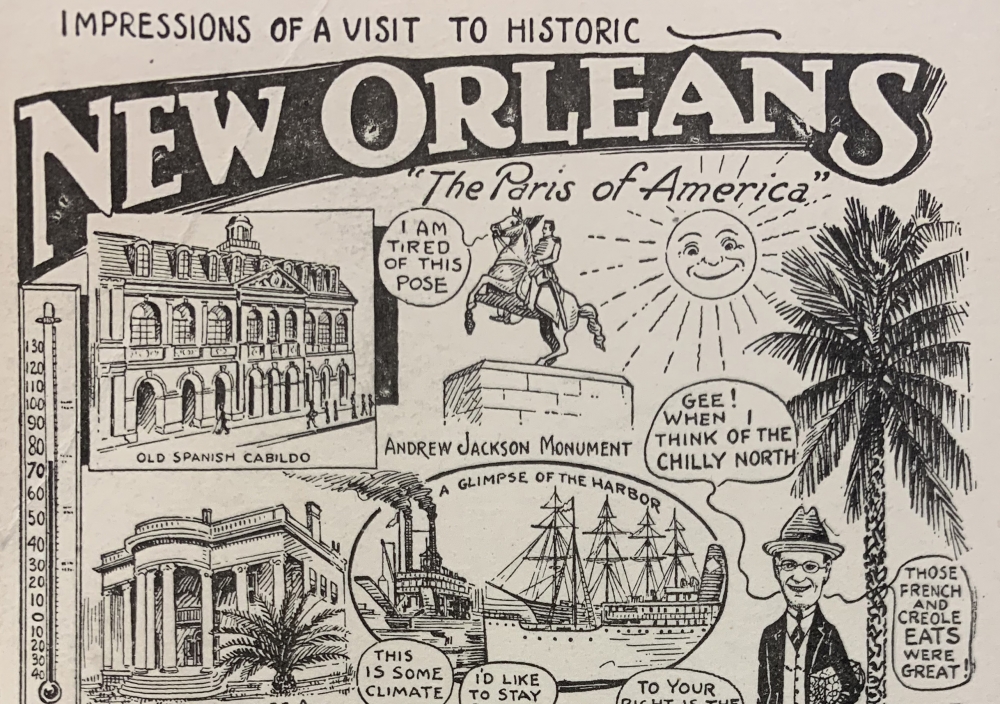

3. The Paris of America?

A 20th-century tourism poster leans into the comparison of New Orleans to Paris. With so many cultural influences, why does this one still define us? (THNOC, 1979.106.5)

The quote: “There is much novelty on New Orleans, to a northern person. Everything is entirely foreign, French, and outlandish. The French language is spoken almost altogether their houses, their manner of doing business, cookery etc. etc. is Frenchified in the extreme. And I would [wonder] if a yankee felt more out of his element in London or Paris.”

The writer: George Endicott, a traveler from the Northeast, writing to his sister in Boston; March 4, 1834.

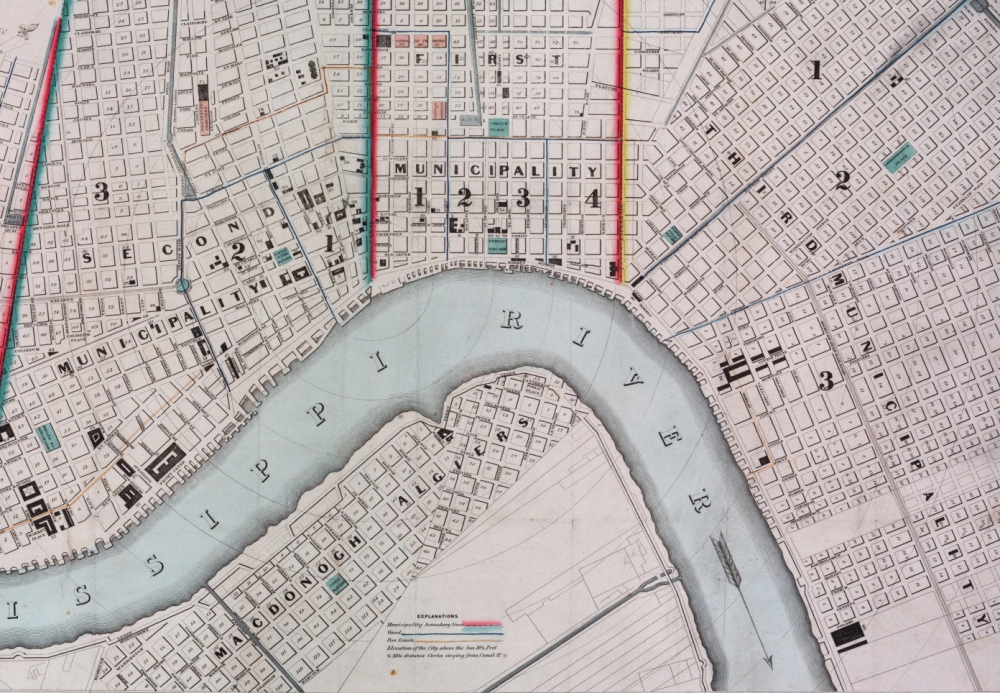

Here’s another example of a writer putting his finger on one of New Orleans’s modern draws, albeit in a backhanded manner. It’s common for writers of this period to itemize, and often grouse about, the many French elements found in New Orleans. Endicott’s letter is probably the most overt example—he goes as far to suggest that a Yankee would feel “more out of his element” in Paris—but other writers note the city’s “Frenchified” aspects, as well. A traveler named Edward Russell even wrote in his journal, in 1835, that the language barrier between French- and English-speaking citizens made it difficult for the legislature and courts to function—the city was divided into three separate municipalities the following year, effectively separating French and English speakers. It would be fascinating to bring Russell to 2019 and ask him if we’re any better off now.

An 1845 map shows how New Orleans was divided into three separate municipalities, effectively separating French- and English-speaking citizens. (THNOC, The L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1949.7 a,b)

Now, 185 years later, this city embraces its Old World-ness when convenient. Just as we live and die by our American Football team, we toss around the pseudo-French phrase “Laissez les bon temps rouler” (Let the good times roll) and celebrate Mardi Gras. Though the city’s cultural staples, including its cuisine, music, and architecture, have remarkably diverse influences, locals and tourists alike continue to liken New Orleans to France. This comparison was even spoofed in a recent Saturday Night Live skit, where noxious tourists, fresh from their trip to the Big Easy, drop some clichés, including: “You put Paris in a swamp, and that’s N’Awlins in a nutshell, baby.” For Endicott, that notion was all too real; he was perturbed by the city’s swampy geography.

These are just three examples of letters that give fascinating views into New Orleans’s past. THNOC has thousands of letters and manuscripts that piece together the stories of people who came through the Crescent City. Drop by the Williams Research Center to read a chapter.

The Williams Research Center is open Tuesday through Saturday 9:30 a.m.–4:30 p.m. at 410 Chartres Street. Access to the Reading Room free and open to the public with no appointment necessary, and the vast majority of THNOC’s catalog is searchable online.

Cover image: Greetings from New Orleans, Louisiana; between 1930 and 1960; postcard by Louisiana News Company; THNOC, gift of Janis Versaggi Williams, 2015.0319.1

Cover image: Greetings from New Orleans, Louisiana; between 1930 and 1960; postcard by Louisiana News Company; THNOC, gift of Janis Versaggi Williams, 2015.0319.1