Note: This article contains detailed and graphic depictions of violent crime. The content may not be suitable for all readers.

A pair of gruesome murders in the French Quarter, remembered as the “New Orleans Trunk Murders,” was one of the most violent crimes in 1920s New Orleans. This story is usually included in The Historic New Orleans Collection’s “Danse Macabre: The Nightmare of History,” a tour that explores the darker aspects of the city's history. The in-person tour is on hiatus, but THNOC's Visitor Services department produced a new series of videos based on the stories.

The Setting

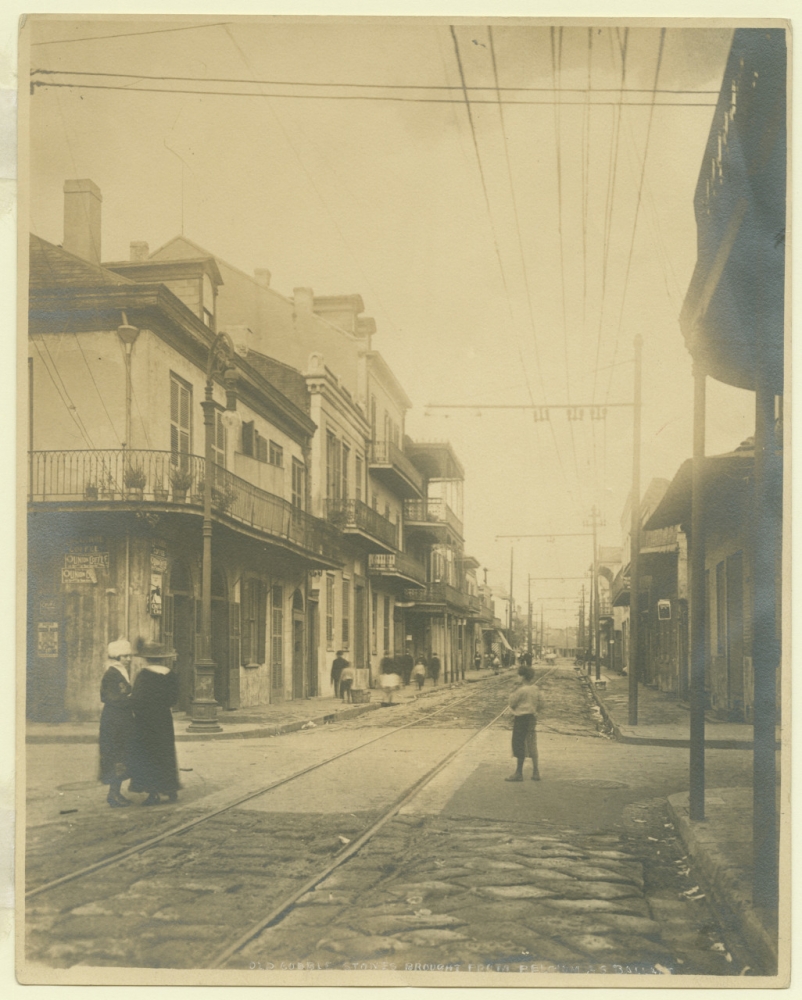

A photograph shows Governor Nichols and Royal Streets in 1928. The French Quarter of the 1920s was a diverse, working-class neighborhood. (THNOC, gift of Mrs. Charles Belik, 1987.25)

The French Quarter of the 1920s is often remembered for the vibrant cultural scene that coalesced around writers such as Sherwood Anderson and Lyle Saxon, and institutions like the Arts and Crafts Club and the Double Dealer literary magazine. Artists, writers, and partisans of the bohemian lifestyle were drawn to the lower rents and old-world aesthetic of the Vieux Carré.

In reality, the French Quarter was still a principally working-class neighborhood, much as it had been since the late 19th century. In the decades after the Civil War, many wealthier residents of old inner-city neighborhoods had moved to garden suburbs along Esplanade Avenue, St. Charles Avenue, and further uptown to escape urban nuisances such as warehouses and sugar refineries.

Meanwhile, the French Quarter had become increasingly home to working-class residents, thanks to decreasing property values and proximity to employment opportunities. Newly arrived immigrants from Sicily settled in large numbers beginning in the 1880s. By the 1920s the neighborhood, especially in the areas closer to Esplanade Avenue, was heavily populated by first- and second-generation Sicilians, who joined the racially and ethnically diverse community.

This lively era in the French Quarter was unfortunately accompanied by a spate of crime. Nevertheless, the “Trunk Murders” stood out as an exceptional case of violence that rattled and captivated the city.

Discovery

The victims of the “Trunk Murders” were discovered October 27, 1927, at 715 Ursulines Street. The property is shown in this 1960s photograph. (By Daniel S. Leyer; courtesy of the Vieux Carré Survey)

On the afternoon of Thursday, October 27, 1927, Nettie Compass entered the second-floor apartment at 715 Ursulines Street to do some cleaning. She had barely set foot inside before encountering traces of blood. Her calls for help attracted the attention of two men nearby, who called the police.

Responding officers uncovered the full horror of the murder scene: two small traveling trunks packed with the expertly butchered corpses of two young women. Blood-soaked mattresses where the victims had lain. Severed fingers on the floor. A bathroom covered in blood.

Orleans Parish Coroner Dr. George Roeling determined that the killer had first bludgeoned the women with a lead billy club, before decapitating them with a machete and amputating their arms and legs.

Authorities recovered a gold wedding band buried in a deep gash in one of the victims’ backs. Clothing that investigators believed had been tossed from the trunks to accommodate the women’s remains was strewn about the tenement alongside discarded human remains.

The victims, both in their mid-20s and both originally from New Iberia, were Theresa and Leonide Moity and were married to the brothers Henry and Joseph Moity.

The Victims: Theresa and Leonide Moity

This image from the New Orleans Item shows Leonide Moity with an unnamed sister and child. Leonide was murdered by her husband’s brother, Henry Moity, along with Henry's wife, Theresa.

The limited information about Theresa Moity and her sister-in-law, Leonide Moity, comes primarily from the testimonies of those involved in the investigation and the tabloid-style press coverage. The newspapers focused most of their attention on the victims’ husbands, who dwelled mainly on the women’s alleged infidelities and careless parenting.

The only window into the women’s interior lives is preserved in a story written by Leonide. Discovered in a cabinet in her bedroom, it’s believed to be a thinly veiled autobiographical account that she had tried to publish in a popular women’s magazine. (A bloodstained rejection slip was also found at the crime scene). The Times-Picayune published portions of the story in a short article about the personal effects left behind by the women.

Leonide is believed to have written the story before moving from New Iberia. Her cautionary tale, presented as a personal letter, speaks of finding joy again after a failed marriage. Despite their poverty, the author writes of living happily with her husband and their young children in her small hometown. Yet she concludes with an ominous warning, “Now to you readers, young girls especially . . . please think ahead of you and do not make the mistake I’ve made, because it does not always turn out the right way, you can still be disappointed. Guess it was only my luck to be happy like this, so I warn others not to take the same risk.”

One line, a piece of advice imparted by her father, haunts her story: “Be careful, for marriage is a life sentence.”

The Suspect: Henry Moity

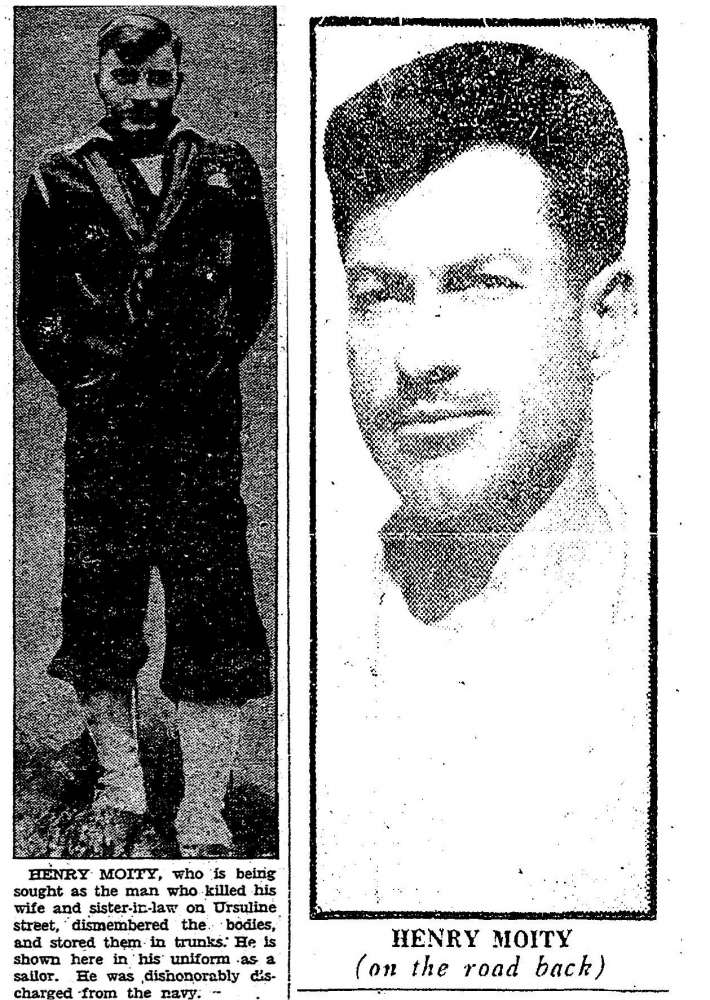

Left: Authorities used Henry Moity’s US Navy portrait to help locate him after the Trunk Murders in 1927. Right: Later in life, Henry Moity made news again, when he was found in St. Louis after escaping prison.

Upon the gruesome discovery of the two murdered women, New Orleans Superintendent of Police Thomas Healey set about locating the husbands. Leonide’s husband, Joseph, turned himself in that evening. Henry, however, was nowhere to be found.

Both couples and their young children lived in the small apartment. Joseph told police he had recently moved in with his sister after catching Leonide with another man. Neighbors reported bitter fights over money, constant accusations of infidelity, and wild drinking bouts in the household.

After determining that Henry had headed to a Camp Street boarding house, where he planned a getaway by ship, Superintendent Healy radioed the seven ships sailing out of New Orleans that day to be on the lookout. Healy’s dispatches to area law enforcement described Henry as having “dark bushy hair,” “very dark brown eyes,” and “tattoo mark on arm, flower with lady face, also nude woman.”

On Saturday, October 29—two days after the women’s bodies were discovered—crewmen of the freighter Gem reported Henry Moity to the Lafourche Parish Sheriff. Henry had begged his way onto the ship using a false name, but the crew recognized his tattoo from the newspaper stories about the crimes.

The Confession

A circa 1925 image shows the criminal court building at Tulane Avenue and Elk Place. (THNOC, gift of Waldemar S. Nelson, 2003.0182.523)

In his confession Henry detailed his motives for the killings, while also insisting that his mind had been warped by alcohol. He was enraged over an affair he believed his wife was having with the couple’s landlord, Joseph Caruso. In Henry’s version of events, he was provoked to vengeance by Theresa’s imminent plans to leave him, in addition to her infidelities and neglect of the children. He also resented his sister-in-law, Leonide, for having what he perceived was a negative influence on his wife.

Henry did not make it hard for prosecutors to prove premeditation. The afternoon before the murders, he told the housekeeper, Nettie Compass—the woman who later discovered the victims—that he should “take a pistol and shoot both of those basterds [sic].” Later that evening, Nettie said she saw Henry, Theresa, Leonide, and the children leave the apartment in good spirits. Nettie testified that she remembered Henry pulling her aside and whispering not to be scared if Nettie and her family heard the children crying in the early morning.

In a Times-Picayune article, parish coroner Dr. George Roeling noted the killer’s skill with a knife at trial, saying, “The killer who decapitated Mrs. Henry Moity . . . knew enough not to try to cut through the bone, but to cut through the joint. The appearance of the head of the wife of the defendant . . . indicated that it had been skillfully removed…” Before coming to New Orleans, Henry had worked as a butcher’s assistant in New Iberia.

The two murders were tried separately by different judges. Henry was found guilty in both cases and sentenced to two concurrent terms of life in prison.

Convict #18038

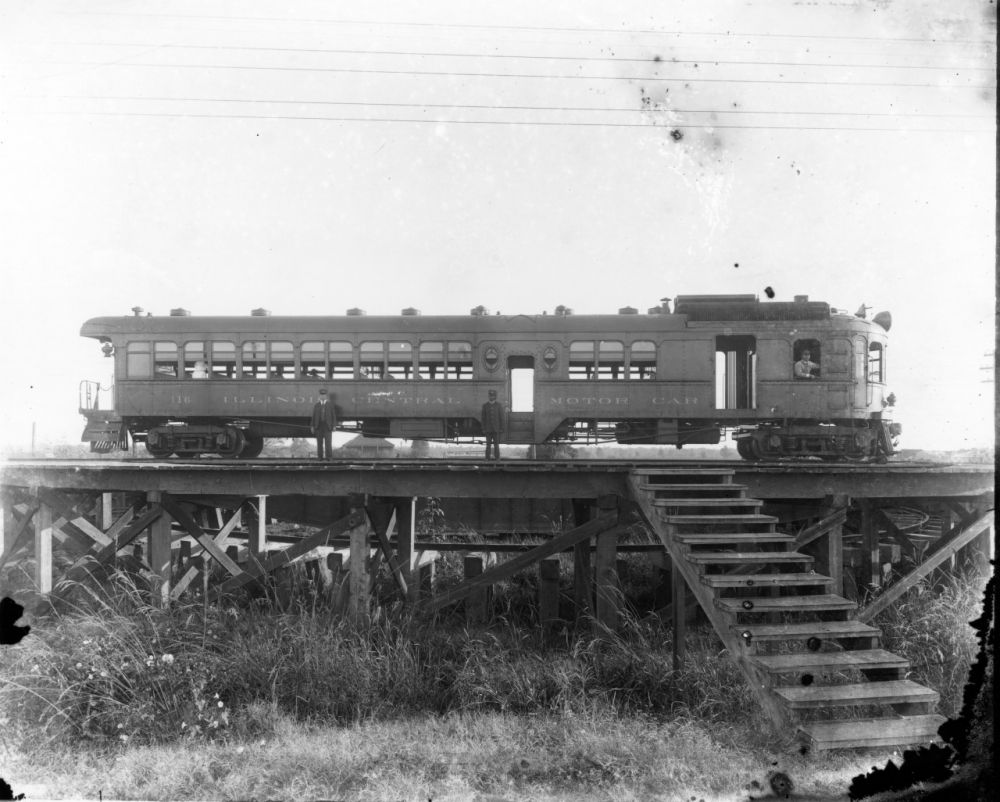

Henry Moity was found guilty and sentenced to concurrent two life terms in prison for the “Trunk Murders,” but he was given considerable leniency and was able to escape. He boarded an Illinois Central train car, like the one seen here, and fled to St. Louis. (The Charles L. Franck Studio Collection at THNOC, 1979.325.6081)

Henry began his sentence at Louisiana State Penitentiary on July 6, 1928. He appears to have enjoyed remarkable leeway for a man convicted of two brutal murders. In 1934 Henry was made a “trusty” of the prison, meaning he was given responsibility for special assignments and was less heavily guarded than other prisoners.

In the summer of 1944, on a routine trip to the post office, Henry simply hired a taxi to take him to Hammond, Louisiana. From there he caught the Illinois Central Panama Limited en route to Chicago. George Provosty, then superintendent of prison camps in Louisiana, seemed unconcerned. He predicted Henry would soon return of his own accord, since he had served 16 years of his sentence and had a chance of being pardoned due to temporary insanity (due to his consumption of alcohol) at the time of the killings.

Two years later in 1946, Henry was stopped for suspicious behavior by police in St. Louis, Missouri. When he admitted his identity, he was returned to prison in Louisiana. Despite his two-year sojourn, the Louisiana Pardon Board recommended his release in 1947. On March 26, 1948, Governor Jimmie Davis signed the pardon. Twenty-one years after killing his wife and sister-in-law, Henry Moity was free.

His early release turned out to be a terrible mistake that nearly cost another young woman her life. After getting out of prison, Henry moved to California in hopes of restarting. At a Los Angeles hotel in 1956, Henry shot his girlfriend Alberta Orange in the chest, puncturing her lung. He was sentenced to five years at Folsom Prison for attempted murder and assault with a deadly weapon.

Henry died of a stroke in 1957 while serving his term at Folsom. Memory of his crime survives in part due to the themes this true story shares with a popular French Quarter ghost story.

The “Sausage Ghost” of Ursulines Street

The building at 715 Ursulines Street still stands today, in a block that has been the site of more than one gruesome crime. (Photograph by Eli A. Haddow)

Recounted, among other places, in Lyle Saxon’s collection of Louisiana folk tales, Gumbo Ya-Ya, “The Sausage Ghost” legend tells of mid-19th-century German immigrants Mr. and Mrs. Hans Muller, who opened a sausage factory on the ground floor of their property at 725 Ursulines Street, just a few doors down from the building where the Moity family lived. The story goes that Hans Muller killed his wife, and, to hide his crime, made sausages out of her body and served them out of his butcher shop for weeks—only to be found out after a customer bit into a piece of Mrs. Muller’s wedding ring. Her ghost is said to have haunted the shop until Muller went insane.

Henry’s past employment as a butcher’s assistant was a key point in his two trials. And on November 2, 1927, from behind bars awaiting trial, he is reported by the Times-Picayune to have threatened the man with whom he believed his wife had been unfaithful: “If I ever get my hands on that Joe Caruso, I’ll chop him up into little pieces, not big pieces like my wife, but little pieces—my God, I’ll make him look like something that’s been run through a sausage mill!”

This story appears on THNOC’s tour “Danse Macabre: The Nightmare of History,” which explores the darker side of New Orleans history.

About The Historic New Orleans Collection

Founded in 1966, The Historic New Orleans Collection is a museum, research center, and publisher dedicated to the stewardship of the history and culture of New Orleans and the Gulf South. Follow THNOC on Facebook or Instagram.