As a museum, research center, and publisher, The Historic New Orleans Collection is constantly collecting new objects for its extensive holdings. Below, you’ll find four recently acquired objects or collections that touch on the history of New Orleans and the Gulf region. These include a unique photographic album by a pioneering female photographer and three new additions relating to the region's music.

1. Views of the Ursuline Convent, New Orleans La., by One of the Sisters

An image from Mother St. Croix’s photograph album looks over the convent with the Mississippi River in the background. She titled the image “Southwest view from tower.” (THNOC, 2018.0242.7)

Among The Historic New Orleans Collection’s most remarkable recent additions is a photograph album by the late 19th-century pioneering female photographer Mother St. Croix, an Ursuline nun who arrived in New Orleans in November 1873. In 37 albumen prints, taken between 1888 and 1894 and printed from 6 1/2" × 8 1/2" glass negatives, St. Croix documented life at the Ursuline Convent on Dauphine Street in the Ninth Ward. The Ursulines moved to this convent from their original French Quarter location in 1824 and remained there until 1912. While a handful of other female photographers appear in contemporary city directories, their work seems to be limited to studio portraits—making St. Croix the earliest known woman to photographically record daily life in New Orleans.

Born Marie Faureaud in Clermont-Ferrand, France, in 1854, St. Croix entered the missionary branch of the Ursulines at Beaujeu in February 1873. In October of the same year, she received her religious habit and the name Marie de la St. Croix. In late November, she arrived in New Orleans with boundless energy, a calling to teach (she was famed for her needlework skills), and the desire to learn photography. According to a 1947 article on St. Croix in the Times-Picayune, she quickly became an accomplished photographer under the instruction of Edward H. Claudel, a local optician, and Father Albert H. Biever, the Jesuit priest who founded Loyola University New Orleans.

St. Croix’s photography was also encouraged by the Mother Superior of the convent, Mother St. Ignatius. In 1899 Mother St. Ignatius commissioned one of the sisters to purchase a new camera for St. Croix when attending a conference in Rome. The new camera allowed St. Croix to use 14" × 17" glass plates, in addition to 6 1/2" × 8 1/2". In 1904 she provided large prints for display in the Palace of Education at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis. Those prints, signed simply “Photo by a Sister,” are now in the collection of the Louisiana State Museum.

Another of St. Croix’s images shows a group of girls at refectory tables sharing a meal. (THNOC, 2018.0242.20)

The photographs in the album acquired by THNOC include views of the convent buildings and classrooms, as well as the sisters and students going about their routines. St. Croix also captured the surrounding neighborhood with the Mississippi River in the background. The convent was a cloistered community, with a 15-foot-tall board fence surrounding the property. St. Croix’s exterior views were accomplished from either the tower of St. Ursula Hall (completed in 1893) or from one of several second-story balconies off the main building.

St. Croix continued to photograph after the Ursuline community moved to a new convent, on State Street, in 1912. The new location even had a darkroom for her use. But after the move, St. Croix’s work became less inspired and appears to have been done primarily for public relations purposes. There are fewer photographs of the new convent and none of life outside the convent walls. Mother St. Croix died at the convent on July 15, 1940, at the age of 86. The album is the cornerstone of her photographic legacy and a rare example of early photography by a woman. It also provides a glimpse into the daily life of one of New Orleans’s oldest and most revered institutions.

—Jude Solomon

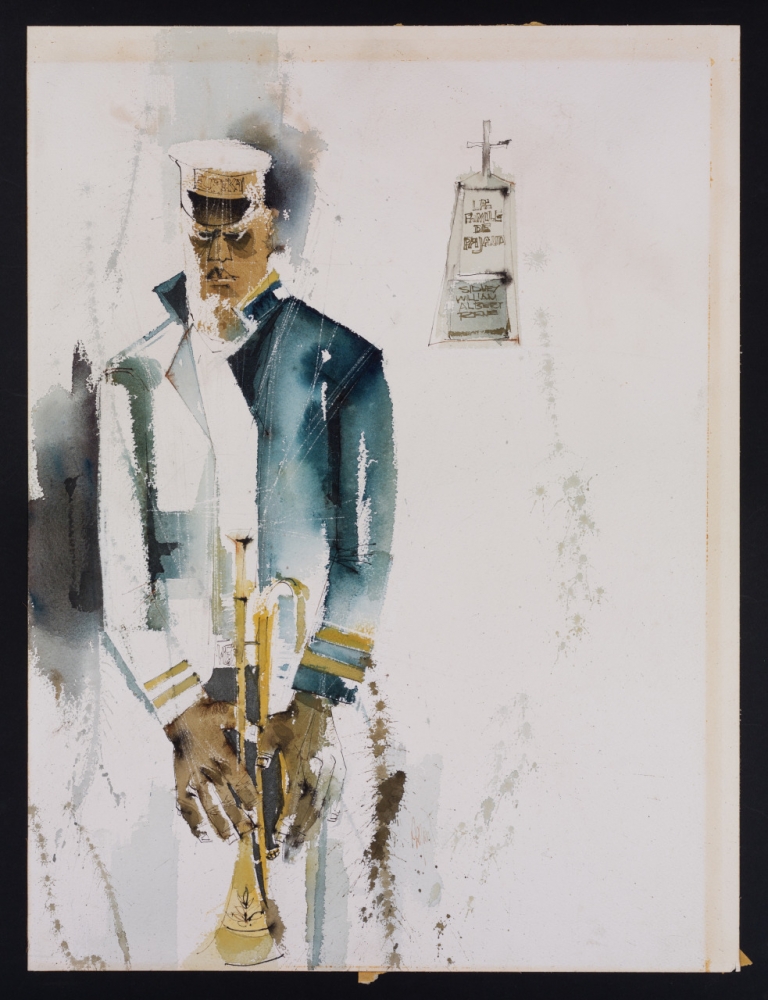

2. La Famil[l]e de Pajaud (Sidney William Albert Renee)

William Pajaud Jr.'s watercolor depicts pieces of a New Orleans jazz funeral. (THNOC, 2018.0490)

Born in New Orleans, the artist William Pajaud Jr. (1925–2015) was the child of Audrey DuCongé, a social worker, and William Pajaud Sr. (known as Willie), a trumpeter who played regularly for jazz funerals and for a time with the Eureka Brass Band. William Pajaud Jr.’s early exposure to the brass band and traditional jazz scenes in New Orleans informed the art he created throughout his life. After graduating from Xavier University of Louisiana with a bachelor’s degree in fine art, Pajaud left New Orleans during the era of the Great Migration, moving first to Chicago and then Los Angeles, where he would spend the remainder of his life. He studied at the Chouinard Art Institute (now California Institute of the Arts), and in 1957 he joined the staff of Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Company, one of the largest African American–owned insurance companies in the West. During his tenure at Golden State, he developed the company’s nationally recognized collection of African American art.

Pajaud’s watercolor La Famil[l]e de Pajaud (Sidney William Albert Renee) evokes a New Orleans jazz funeral, while memorializing the artist’s paternal relatives. An unidentified Eureka Brass Band trumpet player, likely Willie Wilson, stands in front of a tomb, on which the names of Pajaud’s grandfather, father, and uncles are inscribed. The subject’s gaze and downward facing trumpet reflect the moment of burial, when bands are traditionally silent.

THNOC’s extensive music holdings include film and photographs of the Eureka Brass Band, but this painting adds a new perspective on the band’s rich history, as well as the city’s music and funeral traditions. It is also the first work by this important New Orleans–born artist in the institution’s holdings.

—Eric Seiferth

3. Les lys et les roses

Octavie Romey’s Les lys et les roses contains this illustration of two women. (THNOC, 2016.0296)

Les lys et les roses, an elegantly bound album of eight pieces for piano and voice by Octavie Romey, opens a window on the role of women in New Orleans’s 19th-century music scene. Born in Paris in 1824, Octavie Romey was the daughter of prominent historian and translator Charles Romey, best known for his Histoire d’Espagne (1839). The exact date of her arrival in New Orleans is unknown, but she would become one of the city’s earliest known female composers. In her early years in the city, she collaborated with Eugène Prévost, composer and conductor for the French Opera House and the Orleans Theater. By the late 1850s, Romey was attracting local press coverage for her piano concerts.

Les lys et les roses was published circa 1841, before Romey moved to New Orleans. The Parisian journal La France littéraire praised Romey’s compositions as “sweet and pure romances.” The lyrics are by French novelist, poet, and dramatist Mélanie Waldor, and lithographs by Paul Gavarni accompany the pieces.

During her years in New Orleans, Romey is known to have published three pieces of sheet music: “La Marseillaise et le Bonnie Blue Flag: Grand fantaisie de concert” (1864), which is also in the holdings of The Collection; “Le chant exile” (1858); and “4 Mars. Souvenir!! À la mémoire de Madame G. T. Beauregard” (1864). The latter piece was a tribute to the second wife of Confederate general P. G. T. Beauregard, Marguerite Caroline Beauregard, whose funeral on March 4, 1864, was a citywide event. After the Civil War, Romey directed and performed in a series of successful benefit recitals for Confederate widows and orphans, often featuring orchestras composed entirely of women.

Romey also organized “monster concerts” in New Orleans. A 19th-century musical vogue popularized by New Orleans–born Louis Moreau Gottschalk, monster concerts featured major works transcribed for multiple pianists performing on stage simultaneously. Romey presented monster concerts at Odd Fellows Hall in 1866 and at Grunewald Hall in 1874, both featuring 24 women on 12 pianos performing her transcriptions of four grand opera overtures.

Romey continued to appear in concerts into the 1870s, and was both the composer and conductor of masses for all-female choirs at Immaculate Conception Church and the St. Louis Cathedral in 1875. She returned to Paris in 1880, where she died the next year. Romey’s lasting legacy was her strong interest in developing and publicly presenting the talents of amateur female musical artists—a very unusual pursuit at a time when the musical skills of women were largely confined to entertaining family and close friends.

—Pamela D. Arceneaux

4. Jimmy Maxwell Orchestra papers

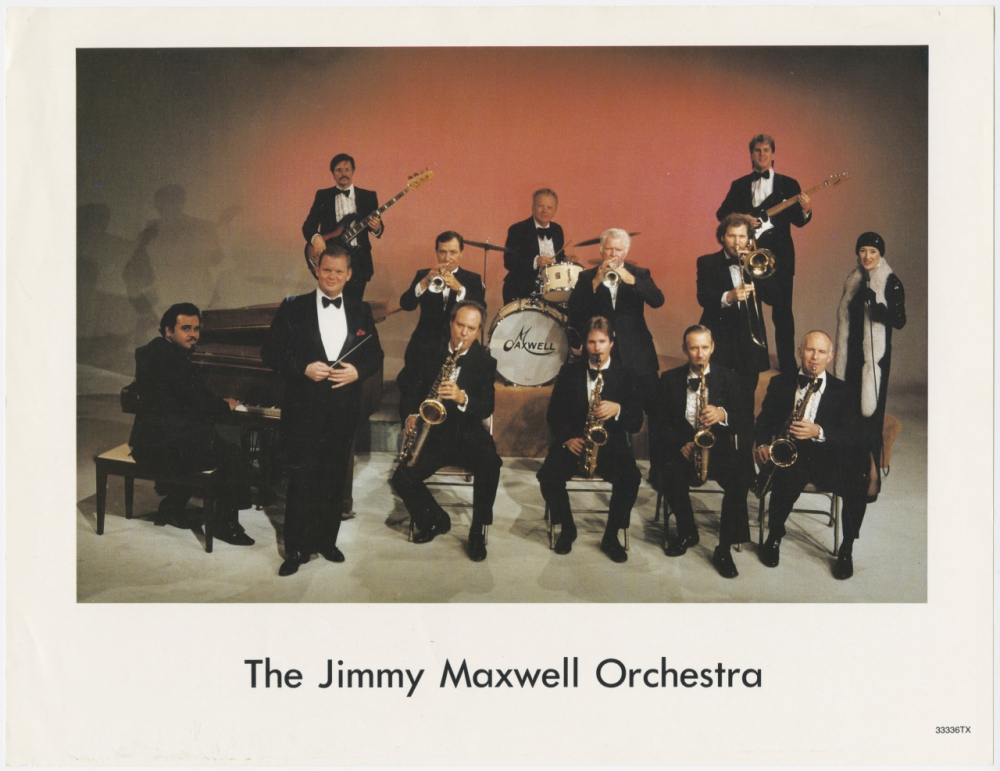

A promotional poster for the Jimmy Maxwell Orchestra, probably from the 1980s, includes a 13-member band. (THNOC, gift of Jimmy Maxwell, 2018.0343.4)

A recent donation from bandleader Jimmy Maxwell provides a fascinating glimpse into the activities of working musicians in New Orleans over the past 70 years. Since the early 1980s the Jimmy Maxwell Orchestra has played steady gigs for Carnival balls and numerous other social events. Jimmy’s father, Eddie Maxwell, was a drummer in the René Louapre Society Orchestra, also a Carnival-ball headliner, for many years before he joined Jimmy’s band. The combined musical careers of Eddie and Jimmy span eight decades. The donation, which includes photographs, diaries, and promotional materials documenting the Maxwells’ involvement in the music business, complements the oral history interviews of Eddie and Jimmy conducted by THNOC oral historian Mark Cave in April 2018.

Among the oldest materials in the collection are Eddie Maxwell’s 24 musical gig diaries covering every year from 1957 to 1982, except 1960 and 1981. Eddie Maxwell recorded information about performance dates, times, and venues; event types; and the amounts of money he was paid. The diaries, which detail the busy schedule of Carnival season and the various events that filled the rest of the year, shed light on the typical annual performance calendar of a big band orchestra member.

Other highlights of the collection include materials related to Maxwell’s Toulouse Cabaret, the jazz venue operated by Jimmy Maxwell and other family members at 615 Toulouse Street in the 1990s, and the Louis Armstrong Society Jazz Band, which was formed in 2001 with Eddie and Jimmy among its members.

—Michael M. Redmann

A version of this story originally appeared in the fall 2019 edition of The Historic New Orleans Collection Quarterly.