On Monday, May, 4, The Historic New Orleans Collection hosted its first-ever #NolaMovieNight, an interactive watch-along of the film The Big Easy. During the event, users watched the movie on their own, and THNOC tweeted behind-the-scenes interviews and historical background on the film. To get more information on the infamous accents used by actor Dennis Quaid and others, we asked local dialect coach Francine Segal (inset), who has worked with actors like Mark Walhberg and Nicolas Cage, to break down the performance. She also filled us in on other actors who have tried—some successfully, others less so—to replicate our local speech patterns.

On Monday, May, 4, The Historic New Orleans Collection hosted its first-ever #NolaMovieNight, an interactive watch-along of the film The Big Easy. During the event, users watched the movie on their own, and THNOC tweeted behind-the-scenes interviews and historical background on the film. To get more information on the infamous accents used by actor Dennis Quaid and others, we asked local dialect coach Francine Segal (inset), who has worked with actors like Mark Walhberg and Nicolas Cage, to break down the performance. She also filled us in on other actors who have tried—some successfully, others less so—to replicate our local speech patterns.

Check out our #NolaMovieNight webpage where you can see our tweets about the film and follow along on your own time.

Below are excerpts from an interview we conducted with Segal leading up to Monday's #NolaMovieNight.

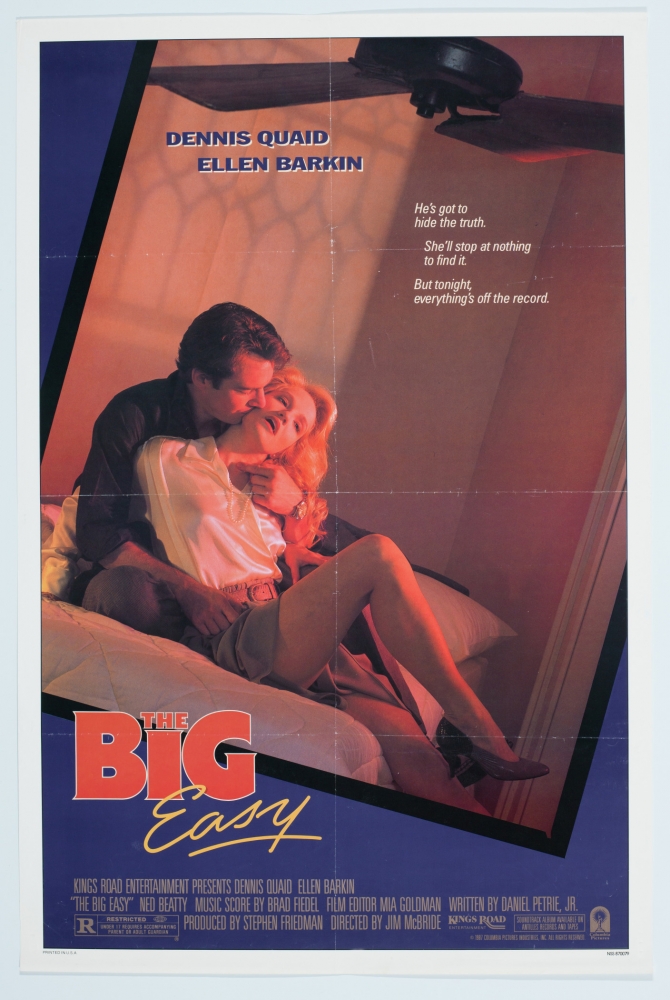

Dennis Quaid and Ellen Barkin starred in the crime thriller The Big Easy, which featured a lot of the city's music and architecture—and some dubious accents. (THNOC, 2011.0300.3)

Q: Why are New Orleans accents so hard to replicate?

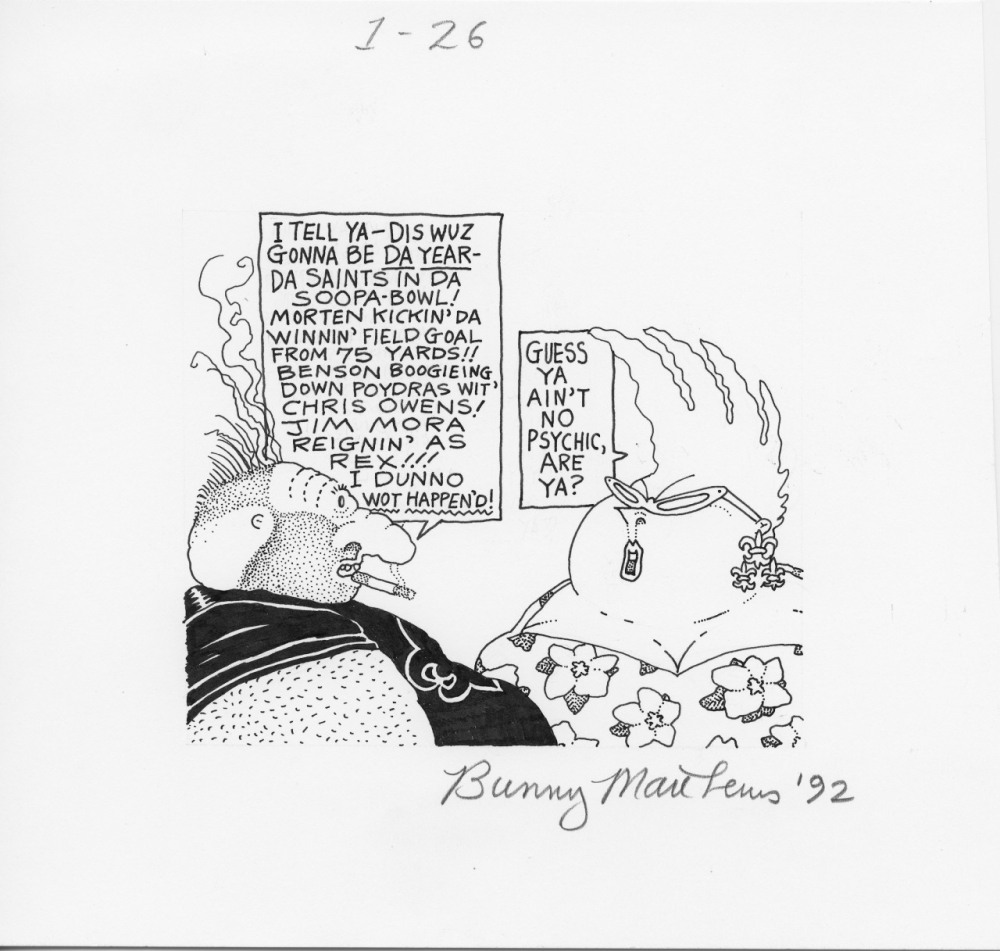

A: Louisiana dialects compose the most diverse and eclectic vernaculars found in the United States. Though “Yat” is the language of the Ninth Ward, the term refers to many variations of Yat in subcultures throughout greater New Orleans. For instance, many educated Uptowners speak a more refined version of the Yat dialect. Mitch Landrieu is a good example.

The Yat dialect has its influences from the Louisiana French and other European immigrants who came to port cities in the 19th century. That is why New Orleans sounds are similar phonetically to areas of New York. Many filmmakers and actors, after hearing an authentic New Orleans accent, reject it because their ear is not used to hearing it and it does not meet their perceptions of a Southern sound. Yat is a difficult dialect to learn and many film actors do not have the training, instincts, and commitment to learn it.

I believe their expectations are based on old movies that take place in New Orleans in which the characters slurred their Rs and elongated their vowels. I have worked with many actors who believed that Blanche DuBois as played by Vivien Leigh in A Streetcar Named Desire used the quintessential New Orleans accent. They are mistaken. Blanche is from Laurel, Mississippi, and Leigh’s dialect is appropriate for a Southern accent of that time period.

Local artist Bunny Matthews depicted "Yat" patterns of speech in his Vic and Nat'ly characters. Segal said that the "Yat" accent is hard for actors to accept, given their preconceived notions about southern speech. (THNOC, ©Bunny Matthews, 1992.39.15)

So, why is history repeating itself, over and over again, with inaccurate New Orleans accents depicted in films about New Orleans?

I believe many filmmakers do not understand that the actor’s process of properly learning a dialect in the left brain needs ample prep work before shooting begins. Everything happens fast in film and especially in TV production. Attention to detail and proper research are often minimal and the focus on the correct dialect for a film is quite often an afterthought.

When I worked on American Horror Story: Coven, the character of Kyle Spencer (played by Evan Peters) was supposed to have a Ninth Ward accent and I was given less than four days to coach the actor. Fortunately, Evan had a good ear and worked diligently with me on phonetics, transposing the script into Ninth Ward sounds, MP3 recordings, and learning rhythm in the dialect by singing Dr. John songs. I always create a written Dialect Road Map for the actor to use. We even went to Liuzza’s and hung out at local bars so he could hear the dialect. I was finally satisfied with his assimilation of the accent. When the producer, Ryan Murphy, heard the actor’s accent, he rejected it for the series. Why? Because Murphy insisted that his US and international audience would perceive this strange-sounding accent with Bronx overtones as a violation of their perception of the South.

Who tried but failed?

Dennis Quaid was fully committed in his mélange of accents for The Big Easy, which he tried to pass off as Cajun and failed with aplomb. Doing Cajun is tricky. And one cannot get away with it by sticking in “cher” at the end of every other sentence. As with most regional dialects, the old-school Cajun dialect is losing its purity and becoming homogenized with more neutral speech patterns as younger generations are exposed to media.

Charles Ludlam, who played the befuddled attorney Lamar Parmentel in The Big Easy, spoke with a drippy Southern accent by elongating his vowels into triphthongs. This clichéd southern dialect has been "Gone with the Wind” for over 50 years, but actors still gravitate to this affected accent today.

The Big Easy is peppered with actors doing a Foghorn Leghorn dialect. In contrast, many of the local actors who played supporting roles sounded authentic. The Big Easy TV series that was shot in New Orleans turned out to have a mixed bag of accents due to time constraints and lack of commitment by producers and actors. When I played a French Quarter pharmacist in this series, I used my natural way of speaking.

Another case in point, Brad Pitt in The Curious Case of Benjamin Button missed the mark by taking the “AR” sound and turning it into a drawl. New Orleanians make the second part of a dipthong sound happen fast. They jump on it and jump off it. This small dialect change would have made him more convincing as someone from New Orleans. (Example: “bad” becomes ba-ed, not ba-ah-ed.) Brad is not alone. Dustin Hoffman in Runaway Jury uses a contrived drawl which discredits his performance. He is in good company with Kevin Costner in JFK who does a laughable Jim Garrison. Faye Dunaway was able to learn a decent Cajun accent for Midnight Bayou but at the last minute got cold feet and turned in a performance with an odd-sounding accent.

Kevin Costner played District Attorney Jim Garrison in JFK. Segal called Costner's accent "laughable." The real Garrison played himself in The Big Easy. (THNOC, 2012.0093.147)

Who nailed it?

As Mama in The Big Easy, Grace Zabriskie had an authentic Cajun accent because she was fluid in the rhythm of a Cajun cadence. A native New Orleanian, Grace was able to have the dialect come out of the action of the character. I believe that a dialect should never be pasted on top of the acting. A dialect is part of the character and it is revealed through the character’s actions and relationships.

David Strathairn turned in a believable Cajun accent in Passion Fish. Believe it or not, Walter Matthau in Casey’s Shadow did a credible job of playing a man of Cajun descent. Bill Holliday did a perfect New Orleans Yat in Tightrope but he played himself. The series Treme had good New Orleans accents for the most part because they did not try to do the accent. When I auditioned for Treme, I was told not to do a dialect and to speak naturally. Many black actors from New Orleans were cast in the show which gave it an authentic sound.

I was fortunate to work with Mark Wahlberg in Deepwater Horizon. He played a character from east Texas who worked on the oil rig. For the record, east Texas and southern Louisiana have similar accents. We sang Willie Nelson and Kenny Rogers songs in order for Mark to learn the rhythm and pitch of the dialect. Singing is sustained speech. In The Runner, Nicolas Cage worked with me to sound like a Louisiana politician in which I used Mitch Landrieu as a model. The accent went in and out.

What tools do you use when coaching an actor on a local dialect?

I have audio files of natives from Louisiana of all ages and different backgrounds which serve as an aid in learning an accent. To teach a Yat accent, I sometimes have clients listen to Al Pacino’s opening monologue in Carlito’s Way, which is an exemplary Yat accent, if you can believe that! Half the battle of learning a dialect is getting the correct rhythm. I find that having the client sing "Such a Night” by Dr. John or “They All Ask’d for You” by The Meters is a nonlinear tool to learn an accent.

Segal says that she encourages actors to sing the lyrics to songs like Dr. John's "Such a Night" to familiarize themselves with the New Orleans accent. (Photograph by Michael P. Smith, ©THNOC, 2007.0103.8.771)

Another helpful tool is to transpose the script into the sounded words of the dialect. If the actor does not know the International Phonetic Alphabet, then I write out the sounds in English. It is important to note that when I coach, the dialect comes out of the acting and so we work on the text with respect to action and what the character wants. It is best if the dialect is organically connected to the acting. The dialect never works when it is a Band-Aid that is epoxied on top of the acting.

Has Hollywood changed its perception of a New Orleans dialect in recent years?

Hurricane Katrina put the New Orleans dialect on the international map through media interviews with Nola residents as well as the displacement of our Nola locals all over the United States. The world heard us. Hollywood is a big ship that moves slowly in changing its biases. I have noted recently that some filmmakers are aware of the challenges of honoring the correct local dialect and make strides to incorporate it in their film. However, this commitment requires more research and efforts by screenwriters, allotting more time for the actors to learn the dialect correctly, and the willingness to dedicate funds for that purpose.

What is your opinion of The Big Easy after all these years?

Maybe it is because of this horrific epidemic that we are facing that I now have a different perspective on The Big Easy. It was released in the 1980s. The film is a throwback to a time of innocence and this depiction of New Orleans is somewhat nostalgic to me, despite all the obvious gumbo/cher/Mardi Gras references. My youthful cynicism about all the mistakes in the film has been replaced with forgiveness. It all seemed so carefree and happy, and I actually enjoyed this film.