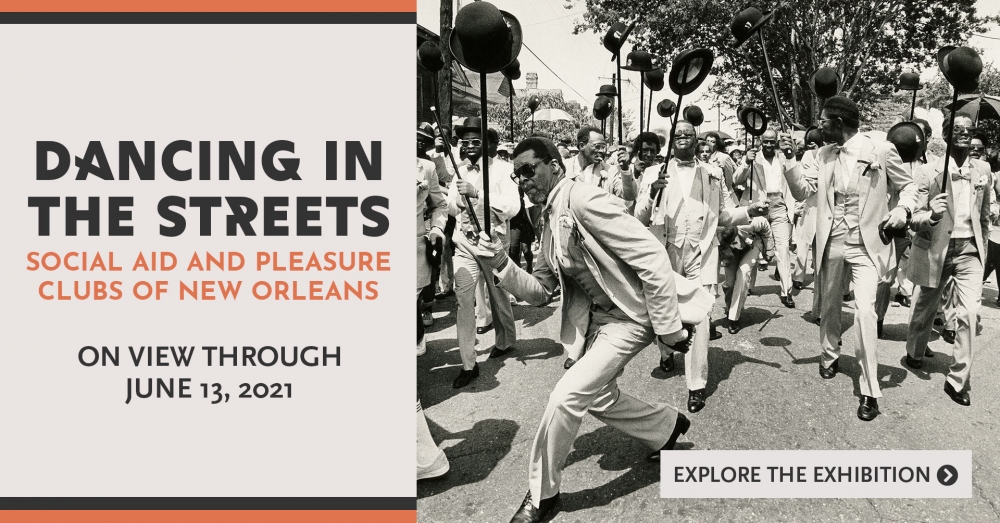

Editor’s note: This story is released in conjunction with The Historic New Orleans Collection’s 2021 Symposium, “Recovered Voices: Black Activism in New Orleans from Reconstruction to the Present Day” and the exhibition Dancing in the Streets: Social Aid and Pleasure Clubs of New Orleans.

On June 11, 1864, the Black community of New Orleans celebrated the end of slavery with an Emancipation Jubilee. Though the Civil War had not yet ended, a new Louisiana government had just re-entered the United States with a new constitution that outlawed slavery, a triumph for the city’s Black population and the loyal supporters of the United States.

Thousands gathered in Congo Square to listen to speakers, sing, and celebrate. Members of Black community organizations, including the Société d’Economie et d’Assistance Mutuelle and its longtime secretary Ludger Boguille, played a prominent role in planning the event. Other Black groups in attendance included the Arts and Metiers, Artisan, Amis, and Français Amis societies, and they were joined by federal troops, local politicians, schoolchildren, teachers, and military bands.

Thousands gathered in Congo Square to listen to speakers, sing, and celebrate. Members of Black community organizations, including the Société d’Economie et d’Assistance Mutuelle and its longtime secretary Ludger Boguille, played a prominent role in planning the event. Other Black groups in attendance included the Arts and Metiers, Artisan, Amis, and Français Amis societies, and they were joined by federal troops, local politicians, schoolchildren, teachers, and military bands.

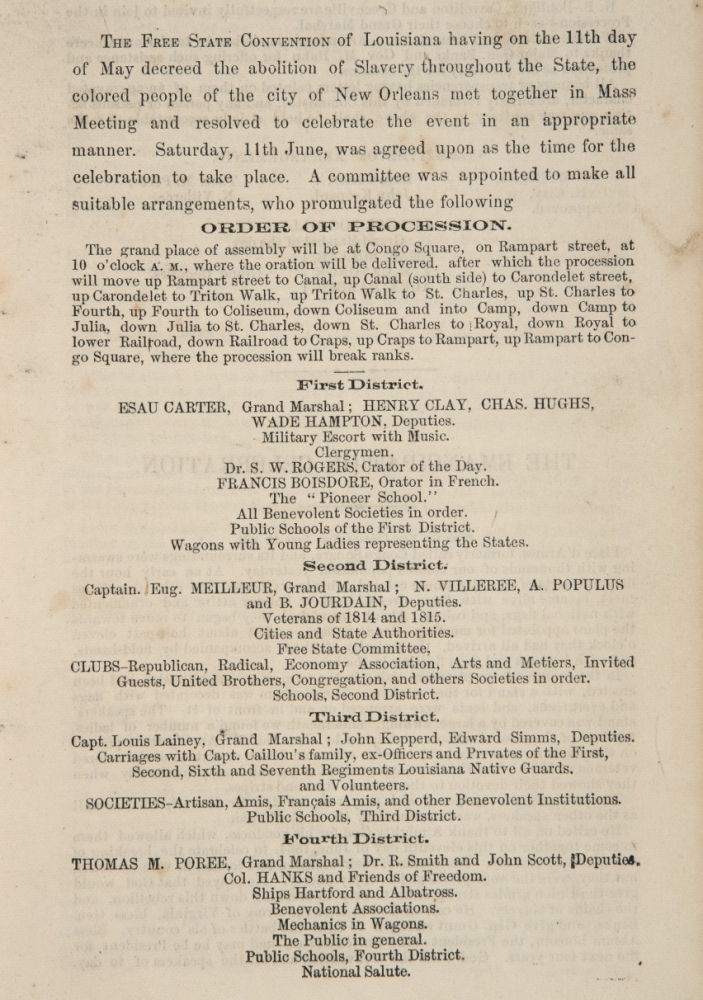

After Louisiana passed a new constitution abolishing slavery, Black organizations paraded in an Emancipation Jubilee on June 11, 1864. This program shows the route and order of parade that accompanied the celebration. (THNOC, 76-781-RL)

Following the program, a parade commenced, in four divisions, filled with the ranks of these loyal societies of Black New Orleanians. They marched up and down the streets of the city with the United States military, together reclaiming the South’s largest and richest metropolis, a place which was thrown into secession by its ruling white elite only a few years prior, and where only weeks before, many Black Americans were legally held in slavery.

There’s a long and rich history of community organizing among Black New Orleanians that predated this event.

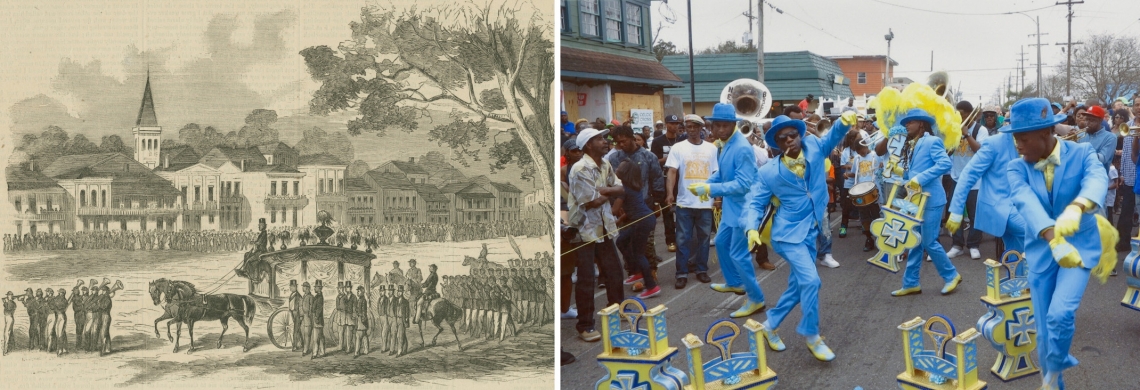

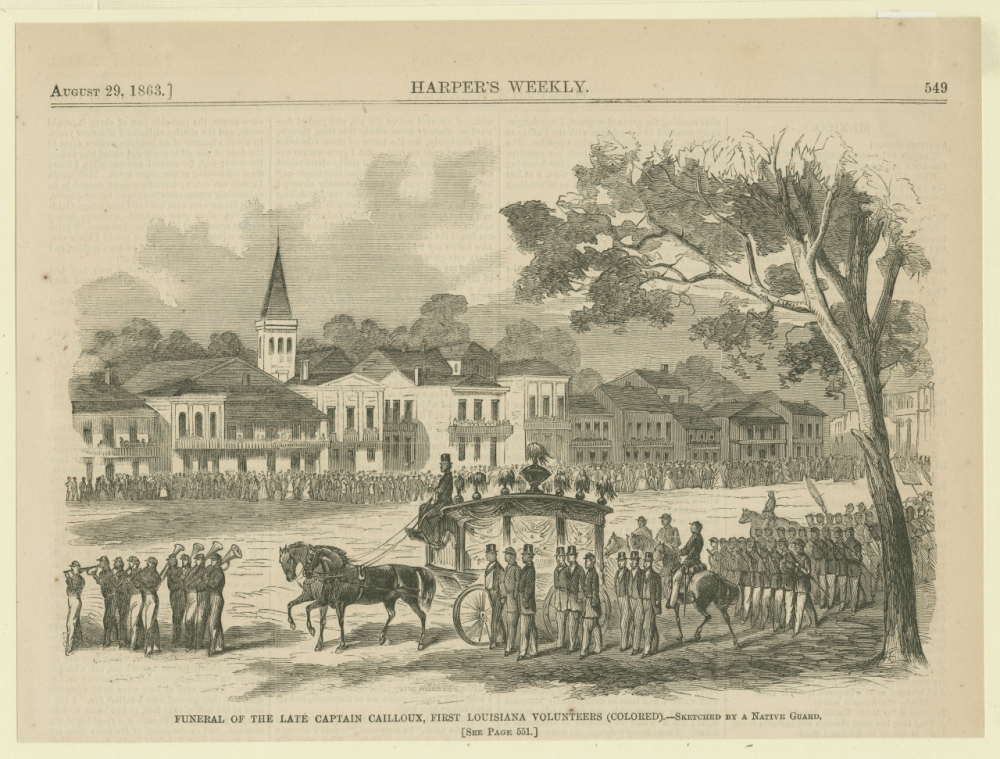

The funeral procession of Captain Andre Cailloux during the Civil War drew large crowds, including many organizations, to the streets of New Orleans. (THNOC, The L Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1958.43.3)

The funeral procession of Captain Andre Cailloux during the Civil War drew large crowds, including many organizations, to the streets of New Orleans. (THNOC, The L Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1958.43.3)

The record goes back at least to the formation of the Perseverance Benevolent and Mutual Aid Association in 1783, being the first of many fraternal, Masonic, mutual aid, and benevolent associations that have flourished in the city over the decades. These voluntary organizations established a local tradition of Black advocacy and celebration in public spaces that carried forward in myriad ways, from the demonstrations and direct actions of the civil rights movement to cultural institutions like the Mardi Gras Indians and Social Aid and Pleasure Clubs.

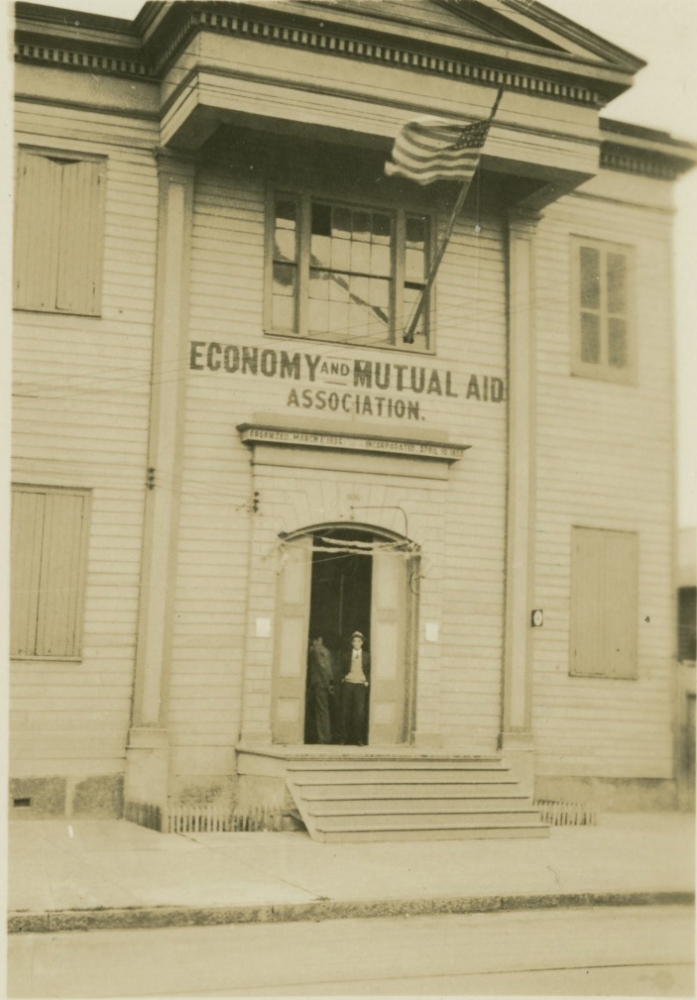

The Société d’Economie et d’Assistance Mutuelle, also called the Economie, which helped organize the Emancipation Jubilee, was one of the most influential of these associations before the Civil War. Leaders in the local free Black community, including many educators, organized the Economie in 1836. In its founding documents they identified virtuousness and morality as the core elements of a strong society and proclaimed a lofty aspiration to “relieve human suffering.”

The meeting hall of the Economy Society is shown here in the 20th century. Leaders in the local free Black community, including many educators, organized the society in 1836. (THNOC, acquisition made possible by the Clarisse Claiborne Grima Fund, 92-48-L.331.133)

The meeting hall of the Economy Society is shown here in the 20th century. Leaders in the local free Black community, including many educators, organized the society in 1836. (THNOC, acquisition made possible by the Clarisse Claiborne Grima Fund, 92-48-L.331.133)

Most Economie members were French-speaking Afro-Creoles, whose influence and already limited rights began to shrink in the lead-up to the Civil War due to racist new laws that enshrined an American racial binary, and demographic changes—the Black share of the population in New Orleans dropped from 40 percent to 15 percent in the 20 years before the war. These challenges made the Economie’s mission all the more urgent.

This lithograph shows New Orleans and the result of the city's enormous growth just prior to the Civil War. (THNOC, The L Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1939.1)

This lithograph shows New Orleans and the result of the city's enormous growth just prior to the Civil War. (THNOC, The L Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1939.1)

The demographic shifts continued as the war came to its end and people began to move. Americans of all backgrounds moved west, no longer encumbered by questions of whether new western states would permit slavery; others moved South, driven by opportunism and/or idealism to participate in the rebuilding of a nation; and there was also a population transition from rural to urban areas.

This last migration involved the relocating of many formerly enslaved Americans who had worked for decades in forced labor camps. The number of African Americans in New Orleans—just above 25,000 when war broke out—more than doubled by 1880. As the city’s demographics continued to transform, its social organizations were forced to respond as the wave of change rippled outward.

A photograph by Theodore Lilienthal shows a busy Canal Street around 1867. In the Reconstruction years, the city's Black population grew as formerly enslaved people left plantations for the cities. (Courtesy of Fritz A. Grobien)

A photograph by Theodore Lilienthal shows a busy Canal Street around 1867. In the Reconstruction years, the city's Black population grew as formerly enslaved people left plantations for the cities. (Courtesy of Fritz A. Grobien)

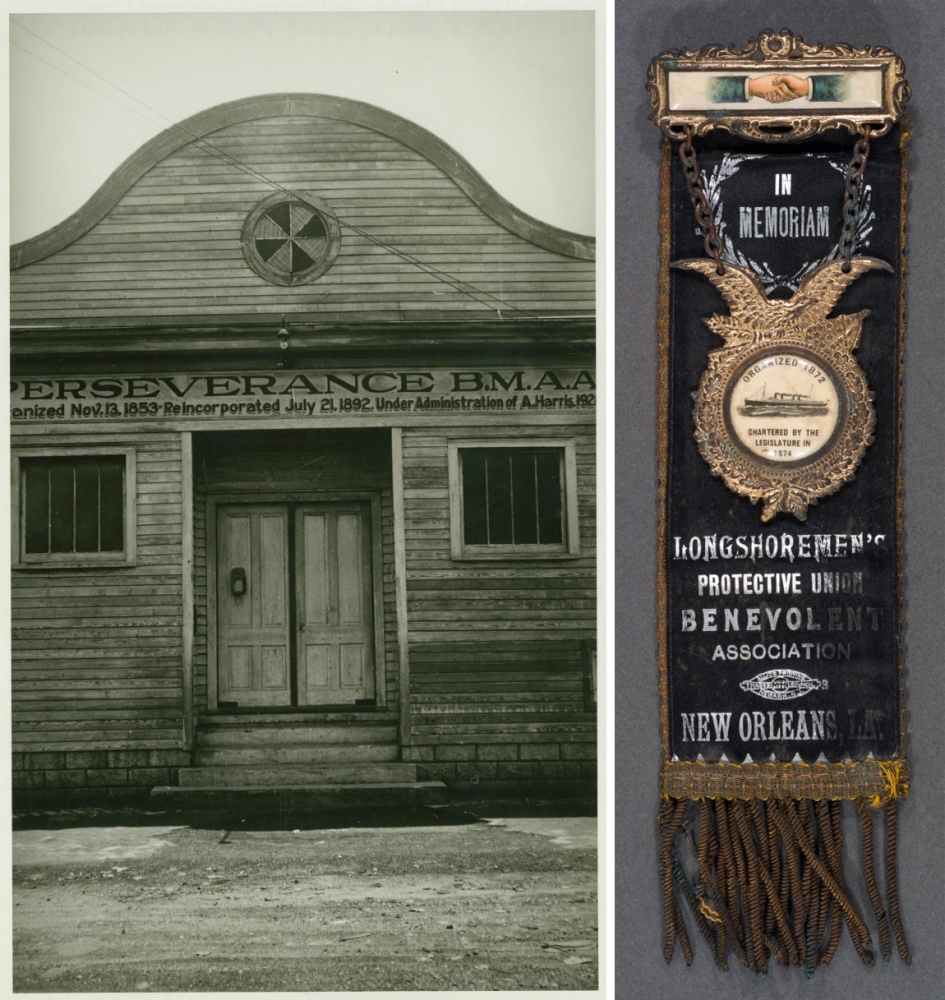

During these years membership in voluntary organizations spiked in New Orleans, as it did across the nation. Benevolent associations, mutual aid groups, unions, fraternal associations, Masonic, political, literary, suffrage and many other groups became a unique element of late 19th century urban life in America.

These groups, diverse in purpose and organization, helped build community and provide social services and purpose for the many new arrivals, including the burgeoning middle- and working-class populations that would define the newly forming urban landscape. Estimates of the number of clubs in New Orleans during the Reconstruction and Jim Crow eras vary, but by the turn of the 20th century, most figures put the number of Black organizations at more than 200, with roughly half of the city’s Black population belonging to at least one group.

Membership in Black voluntary organizations grew after the Civil War. Some predated the war, like Perseverance Benevolent Mutual Aid Association (left), while others like the Longshoremen's Protective Union Benevolent Association were established with the influx of new Black people to the city. (THNOC, acquisition made possible by the Clarisse Claiborne Grima Fund, 92-48-L.331.2648; THNOC, 1978.143)

Many of the older groups formed before the Civil War remained, too. The Economie continued to flourish during the latter half of the 19th century, providing social services and community building for its constituents at a time when racial binarism was eroding nuances of Black identity and civil and political rights were contested for citizens of African descent. In particular, the Economie remained active in politics and the long fight for civil rights for Black Americans.

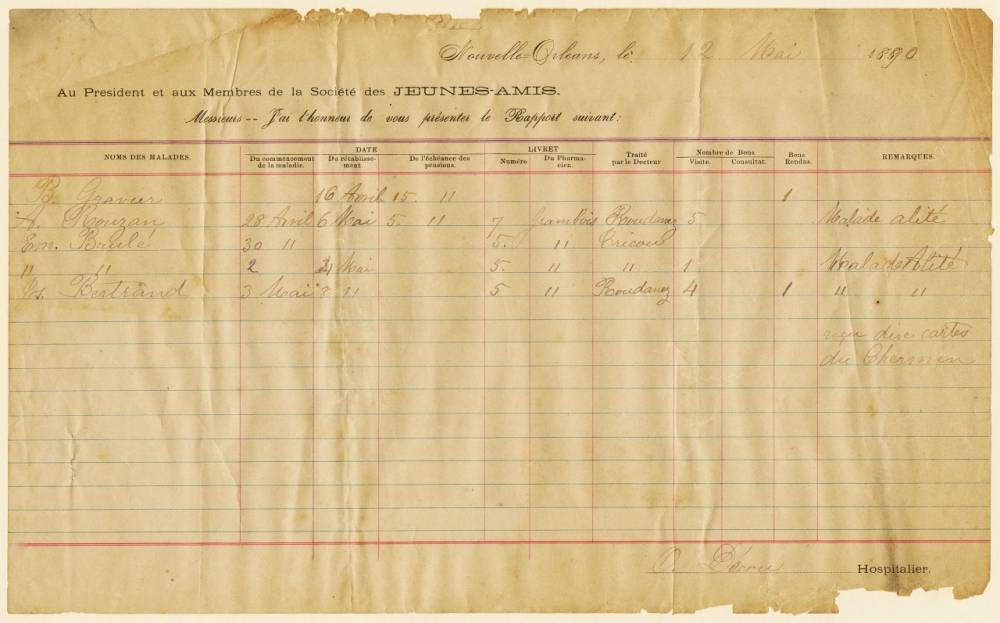

For most organizations in the Reconstruction and early Jim Crow eras, health and end-of-life care predominated as their principal membership services. Before the modern healthcare system, and widespread government-administered social services, membership in a professional, benevolent, or mutual aid society was the most accessible avenue to medical treatment. Typically, sick members would receive care from registered or associated physicians, aid and visitation from other members, and funeral services when they passed away, often including a somber procession with music.

Ledger pages from the Jeunes-Amis organization document medical services provided to its members. (THNOC, acquisition made possible by the Boyd Cruise Fund, 2020.0051.1)

But organizations did much more than provide funerals and social services to their membership. They also built and maintained the ties of community through meetings, events, picnics, and other social engagements sponsored over the course of the year.

Parades became a popular part of the club social calendar as well as a way to visibly take over public space in the city, where many of the civil rights victories won during the Civil War and its immediate aftermath were being erased by local and national legislation. During a meeting of the Economie in 1875, members passed a resolution requiring the club to parade in black-and-white formal attire with musical accompaniment for special events and club funerals. A discussion followed as to what type of music these processions should feature, and what to call it. The answer, laid out in the meeting minutes, was “brass band.”

The English term sticks out in the meeting minutes taken in French. This was something new, something the French language in New Orleans hadn’t yet identified. It was uniquely American. In 1883, the Economie expanded its use of parading with brass bands to their annual anniversary events. This tradition is one that remains to this day in the form of annual anniversary parades, otherwise known as second lines.

The Young Men of Oakdale are shown parading with the Young Tuxedo Brass Band in 1956. The role of Black organizations shifted in the 20th century from providing healthcare and other services to community-building and parading. (THNOC, acquisition made possible by the Clarisse Claiborne Grima Fund, 92-48-L.331.964)

The Young Men of Oakdale are shown parading with the Young Tuxedo Brass Band in 1956. The role of Black organizations shifted in the 20th century from providing healthcare and other services to community-building and parading. (THNOC, acquisition made possible by the Clarisse Claiborne Grima Fund, 92-48-L.331.964)

The number of these voluntary organizations declined in the early 20th century. Needs changed, membership fell, and many organizations ceased to exist. But community organizing persisted. New groups, such as New Orleans CORE, the NAACP and the NAACP Youth Council, the Urban League, Tamborine and Fan formed and led the fight for civil rights and Black empowerment.

By midcentury, a new kind of community-based association had also emerged: the social aid and pleasure club. Neighborhood connections, rather than professional affiliations, drove membership in these clubs. They remained community oriented, via charitable work and sponsorship of social events, but largely left healthcare to the big businesses that would grow to dominate the sector.

Mostly, they paraded.

Members of the Cross the Canal Steppers are shown dancing with fans and baskets in this 2016 photograph by Charles M. Lovell. (©Charles M. Lovell; THNOC, gift of Charles M. Lovell, 2018.0143.2.16)

Members of the Cross the Canal Steppers are shown dancing with fans and baskets in this 2016 photograph by Charles M. Lovell. (©Charles M. Lovell; THNOC, gift of Charles M. Lovell, 2018.0143.2.16)

Members took to the streets in annual anniversary club parades to dance to uniquely American Black music and to take space in a city and country that used legislation to define where they could and could not be. These clubs and their offshoots have continued to parade to this day, establishing the second line tradition that is so deeply woven into the culture of New Orleans.

Learn more about the tradition of New Orleans second lines at our Dancing in the Streets exhibition.

About The Historic New Orleans Collection

Founded in 1966, The Historic New Orleans Collection is a museum, research center, and publisher dedicated to the stewardship of the history and culture of New Orleans and the Gulf South. Follow THNOC on Facebook or Instagram.