Editor’s note: This story is released in conjunction with The Historic New Orleans Collection’s 2021 Symposium, “Recovered Voices: Black Activism in New Orleans from Reconstruction to the Present Day.” The interactive website includes books, stories, videos, and a March 5–7 program. Learn more here.

As the Civil War drew to a close, African American hopes and dreams confronted the reality of entrenched discrimination. In New Orleans, public transportation would become the latest battlefield.

The city’s Black leaders recognized the value of strategic legal action in the pursuit of basic citizenship rights. By dismantling the systemically racist streetcar system, they believed that other policies that created segregated public spaces would soon crumble.

The city’s Black leaders recognized the value of strategic legal action in the pursuit of basic citizenship rights. By dismantling the systemically racist streetcar system, they believed that other policies that created segregated public spaces would soon crumble.

In 1867, inspired by writings in the New Orleans Tribune, African Americans implemented a weeklong coordinated effort of demonstrations to end the segregation practice known as the star car system. In the early years of streetcar usage, due to pressures from the white community, a number of streetcar company carriers instituted a system wherein a small number of streetcars, marked with a star symbol, were available for the black population.

An 1866 stereograph by Theodore Lilienthal shows streetcar tracks under construction on Canal Street. The following year, streetcars played host to one of the first civil rights victories in Reconstruction New Orleans. (THNOC, 2010.0095.13)

An 1866 stereograph by Theodore Lilienthal shows streetcar tracks under construction on Canal Street. The following year, streetcars played host to one of the first civil rights victories in Reconstruction New Orleans. (THNOC, 2010.0095.13)

The war years had led to an awakened Black political consciousness in Louisiana, with a newly freed community enthusiastic about the opportunity to be a part of the political process. They were joined by the state’s large, educated, and prosperous free Black population, already organized around fraternal orders and trades. Lieutenant Governor Oscar Dunn’s success in politics can be attributed to his many networks established through membership in numerous community organizations.

The New Orleans Tribune—the first Black-run daily newspaper in the United States—became the medium that organized and guided the ideals of this community. Early contributors to and supporters of the Tribune would develop a coherent revolutionary program focused on policies in land distribution, Black male suffrage, equality before the law, equal access to public schools, and transportation.

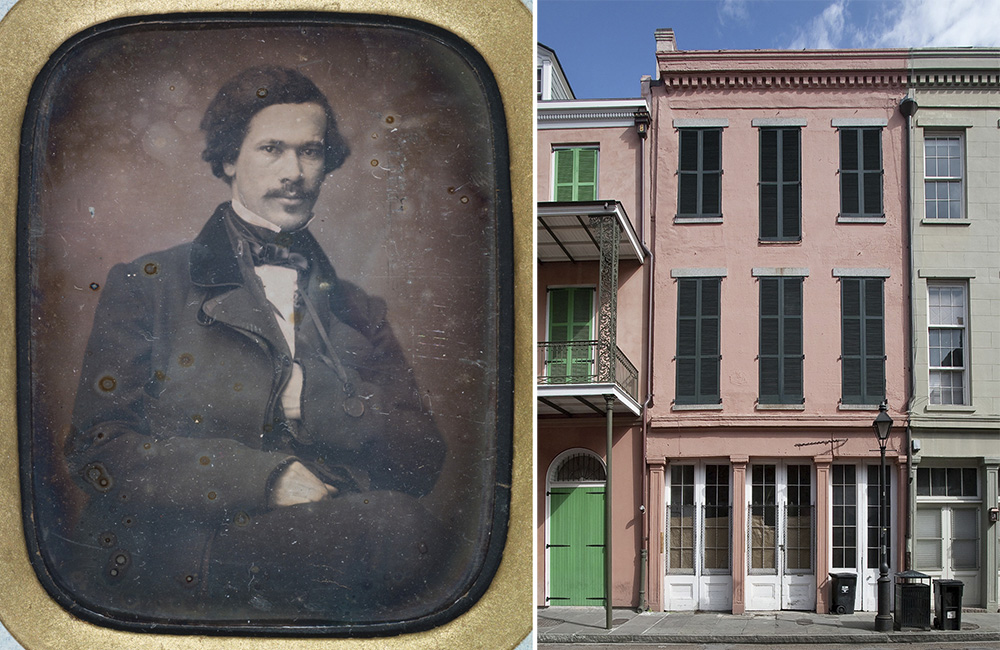

The New Orleans Tribune—the first Black-run daily newspaper in the United States—became the medium that organized and guided civil rights activism in the city. Its co-founder, Dr. Louis-Charles Roudanez, is shown (left) alongside the paper's first offices on Conti Street. (THNOC, Gift of Mark Charles Roudané, 2017.0201.1; courtesy of the Vieux Carré Survey)

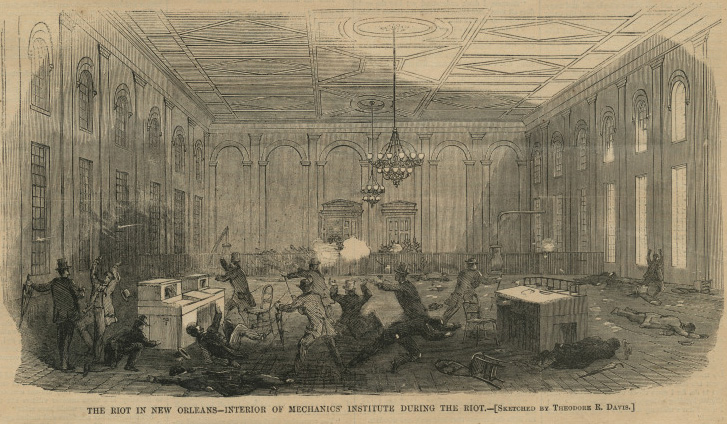

The Tribune detailed the events surrounding the July 30, 1866, massacre at the Mechanics’ Institute in New Orleans. Here, Republicans attempted to reconvene the Louisiana constitutional convention to secure voting rights. The gathering was attacked by a white mob that included police and firemen. According to the Tribune, “black men were assassinated by scores. They fell inside of the hall, outside of the building, in the neighboring streets, and even in distant parts of the city, where they were tracked like dogs.” Tribune editor Jean-Charles Houzeau witnessed the bloodbath and heard the assassins shout “To the Tribune!” He claimed the newspaper was saved by a detail of Black soldiers.

This brutal attack swayed national public opinion and gave Radical Republicans increased clout in Congress in the 1866 midterm elections. This new Congress wasted no time in passing four aggressive Reconstruction Acts. These Acts dissolved the state governments of Louisiana and nine other formerly rebel states; placed Louisiana into a military district with Texas; and established guidelines for the creation of a new state government that included ratification of the 14th Amendment, which would give Black males civil rights and the vote.

A Harper’s Weekly illustration shows the chaotic scene inside the Mechanics' Institute on July 30, 1866, as members of the white mob murder Black people at the Mechanics’ Institute. (THNOC, 1979.200 iii)

In 1866, activists began advancing the argument that the streetcar star system was a violation of civil rights defined by the Constitution and the newly established Civil Rights Act. Now in a more advantageous position politically, the Tribune increased pressure on demands to end discrimination in public spaces.

On April 21, 1867, the Tribune declared: “All these discriminations that had slavery at the bottom have become nonsense. It behooves those who feel bold enough to shake off the old prejudice and to confront their prejudiced associates, to show their hands.” Three days later, on the 24th, the paper published an article advocating for streetcar desegregation and an end to the star car system. The Tribune argued that the US guaranteed equality among the races, but that whites were unwilling to enforce these new rules. The time had come for direct action to achieve desegregation.

Following this call to action, African Americans around the city commenced various efforts to dismantle the segregated streetcar system.

A circa 1867 image shows streetcars and people on Canal Street. Following a call to action by the New Orleans Tribune, protests commenced to dismantle the segregated transportation system. (Courtesy of Fritz A. Grobien)

On Sunday, April 28, words gave way to action. William Nichols, a Virginian-born, Anglicized black painter, forced his way onto a whites-only car and was physically removed by streetcar driver Edward Cox. Nichols was arrested for breach of peace, but two days later the charges were dropped. Within a week of this incident, companies instituted a “do not engage” policy, instructing drivers whose vehicles were boarded by protesters to stop streetcar movement and wait until demonstrators dispersed. This measure was intended to maintain the system of segregation by refusing to engage with activists.

On Friday, May 3, Philippe Duclos-Lange, a Creole Union veteran, tested this policy by boarding a whites-only car on the St. Charles line and holding an hours-long stand-off with the driver. The next day, Joseph Guillaume, a young Creole cigar maker, hailed down a “whites only” car on Love Street (now Rampart Street). When the driver refused to stop, he jumped aboard and took control of the car, leading the Third District police on a chase before his arrest.

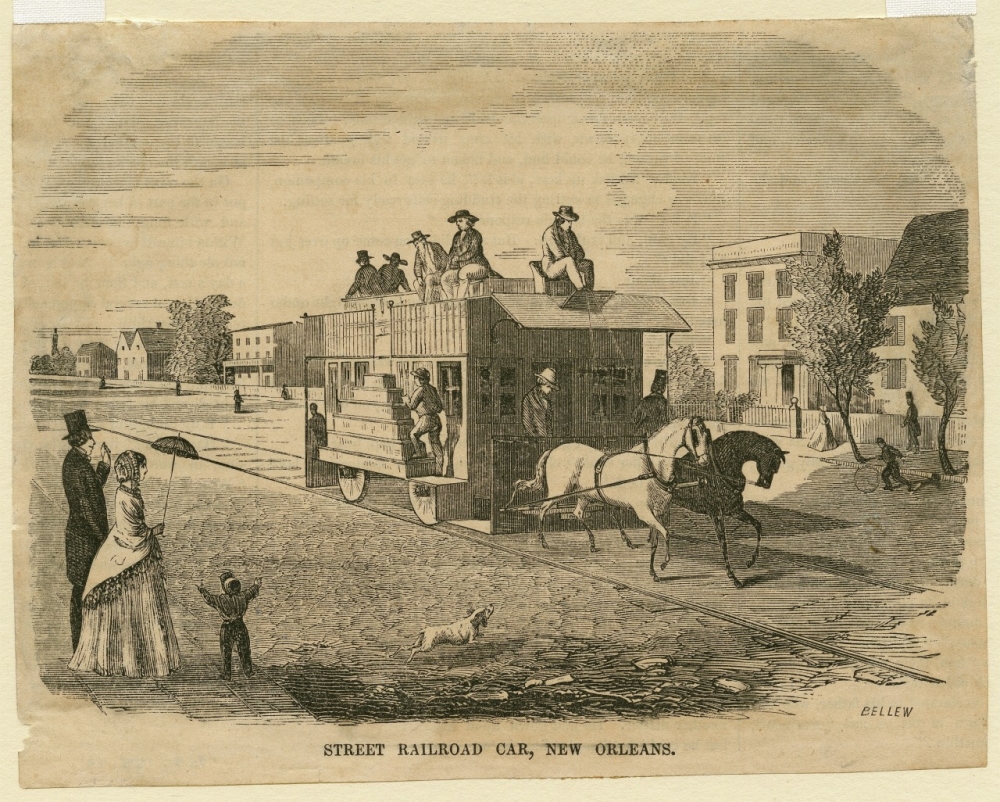

An 1855 illustration shows a horse-drawn streetcar in New Orleans. During the 1867 protests Joseph Guillaume took the reigns of a car and led the police on a chase. (THNOC, gift of Mr. Harold Schilke and Mr. Boyd Cruise, 1959.155.10)

An 1855 illustration shows a horse-drawn streetcar in New Orleans. During the 1867 protests Joseph Guillaume took the reigns of a car and led the police on a chase. (THNOC, gift of Mr. Harold Schilke and Mr. Boyd Cruise, 1959.155.10)

The last day of demonstrations, May 5, proved to be the most intense. Protests concentrated in the downtown Creole faubourgs of Marigny and Treme. Near Washington Square, at the corner of Frenchmen and Great Man (now Dauphine) Streets, two Black women took their place in a whites-only streetcar. When all of the other passengers left the car, the women succeeded in convincing the driver to take them to their destination.

Over half a mile away, a crowd of Black demonstrators at Congo Square grew to 500. Vigilante white mobs began to also gather on the Uptown side of Canal Street. As tension—and the possibility of the crowds converging—began to increase, conjuring memories of the massacre at the Mechanics’ Institute, Mayor Edward Heath called on the crowd to disperse, promising that streetcar policies would be reconsidered.

The next day Mayor Heath met with the railroad company officials and General Philip Sheridan, the officer in charge of Louisiana’s military district. The railroad officials tried to negotiate measures to keep the “star” streetcar system. However, General Sheridan flatly rejected this offer. Railroad officials then met among themselves to weigh the costs and benefits of maintaining a segregated system. Ultimately, they felt that resistance to integration was futile, and they ordered that all drivers permit travelers of all colors to ride the cars.

Although the streetcar protest of 1867 proved successful, a Louisiana law went into effect in 1902 mandating segregation of public transportation. Streetcars would remain segregated spaces for decades. This image, taken in 1951, shows partitioning signs that relegated Black riders to the rear of each car. (Charles L. Franck Studio Collection at THNOC, 1979.325.6222)

The streetcar protest of 1867 is one of the few cases in which African Americans during Reconstruction successfully voiced their dissatisfaction to government officials in the South. By May 8, New Orleans’s streetcars were integrated, and would remain so until Louisiana law mandated segregation in 1902.

Editor’s note: The author wishes to acknowledge his gratitude to the following scholars, whose work informed his telling of this story: Mark Roudané’s “United for Justice” in 64 Parishes; Jeremy Paten and Suzanne-Juliette Mobley’s “Streetcar Protest 1867” for Paper Monuments; Kevin J. Brown “The Star Car” for New Orleans Historical; Mark Charles Roudané’s “Mechanics' Institute Massacre” for New Orleans Historical; Justin Nystrom’s “Reconstruction” for 64 Parishes; John Bardes’s “The New Orleans Streetcar Protests of 1867” We’reHistory; Roger A. Fischer’s “A Pioneer Protest: The New Orleans Street-Car Controversy of 1867” in the Journal of Negro History; and Mishio Yamanaka’s “African American Women and Desegregated Streetcars: Gender and Race Relations in Postbellum New Orleans,” in Nanzan Review of American Studies.

Explore Black activism in New Orleans through our Symposium 2021 website.