The roads, parks, and waterways of New Orleans are lined with historic buildings both grand and small. But here at The Historic New Orleans Collection, we don’t just study those structures that we can see. We care deeply about past landmarks that have since faded into history, or as locals might say, “ain’t dere no more.”

In conjunction with THNOC’s New Orleans Bracket Bash: Lost Landmarks Edition tournament, we present 16 structures that were once landmarks to the citizens of this city—some recently demolished, and some long gone; some that stood for more than a century, and others that lasted just decades. Learn about these buildings (and one unusual structure) below. The bracket tournament ended April 1, 2021, and the Old French Opera House was named fan favorite. See full results here.

As we reminisce about the history of the built environment, we would be remiss to ignore the deeper history of this place. New Orleans arose on the traditional, ancestral, unceded lands of the Houma, Choctaw, and Chitimacha people, and we recognize the enduring, eternal relationship of these Indigenous communities with their land. We acknowledge the intentional erasure of the Indigenous people in Southeast Louisiana, and we are working to promote a better understanding of this history. Through the study of history, collectively we become architects of a more equitable future. For more to the story, listen to this episode of TriPod, which features Native voices sharing their histories of New Orleans.

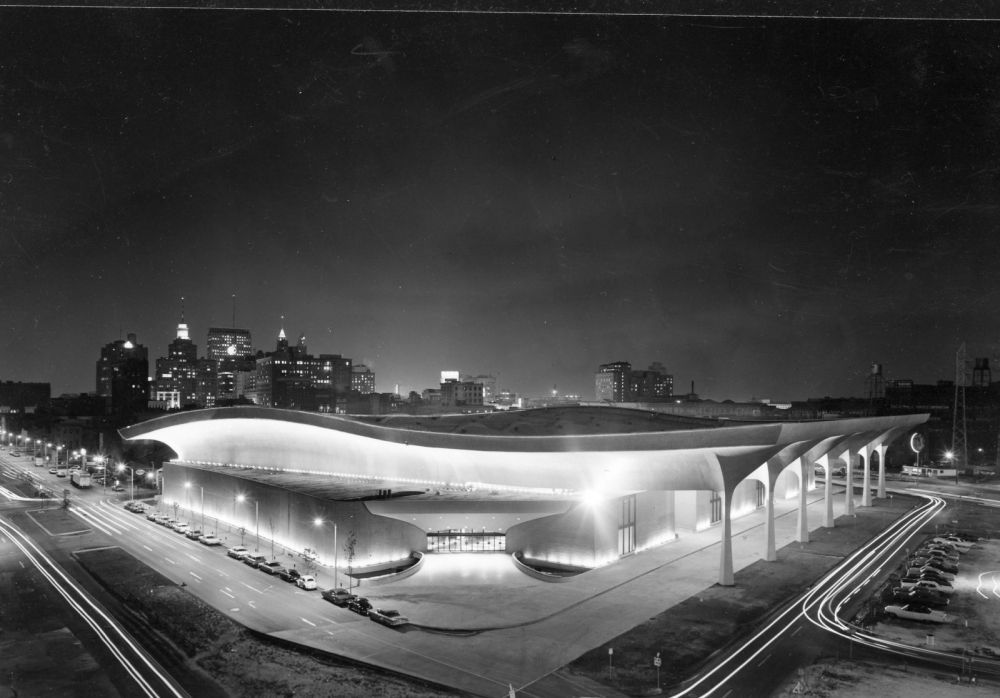

1. Rivergate Convention Center

Image courtesy of the Southeastern Architectural Archive, Special Collections Division, Tulane University Libraries.

The modernist Rivergate Convention Center at the foot of Canal Street, built in 1968, was designed by the architecture firm of Curtis and Davis, which later designed the Superdome. The Rivergate’s concrete roof was only five inches thick but curved and undulated along a breadth of 253 feet. In 1972 the city embellished its dramatic façade with the unveiling of the gold Joan of Arc sculpture that now graces the entrance to the French Market on Decatur Street.

The Rivergate served as a hub for all manner of events, but in the lead-up to the 1984 Louisiana World’s Fair, construction began on a new venue on Poydras Street eventually named the Ernest N. Morial Convention Center. In 1995, despite an outcry from preservationists, the Rivergate was demolished. The Harrah’s casino was built on the site in 1999.

2. Temple Sinai

Image taken in the 1920s. (Charles L. Franck Studio Collection at THNOC, 1979.325.2455)

Temple Sinai now occupies a prominent corner on St. Charles Avenue near the universities, but its congregation originally gathered at an eye-catching structure on the corner of Carondelet and Calliope Streets. The Romanesque-Byzantine structure was designed by Charles Lewis Hillger and completed in 1872. The Jewish temple’s 115-foot-tall double towers, as historian Richard Campanella has noted, made an impressive architectural statement in a city skyline peppered with Christian steeples.

The congregation moved farther uptown to a more modern space in the late 1920s, and their old building was repurposed for a variety of uses, including commercial offices and a theater. The stunning structure was demolished by 1977 to make way for more modern developments, and the site is now occupied by the WDSU building. The building isn’t entirely gone, though: Its iconic spires were salvaged and now grace the top of a structure with its own unique history at the end of Bottinelli Place between Gates of Prayer Cemetery and St. Patrick Cemetery No. 1.

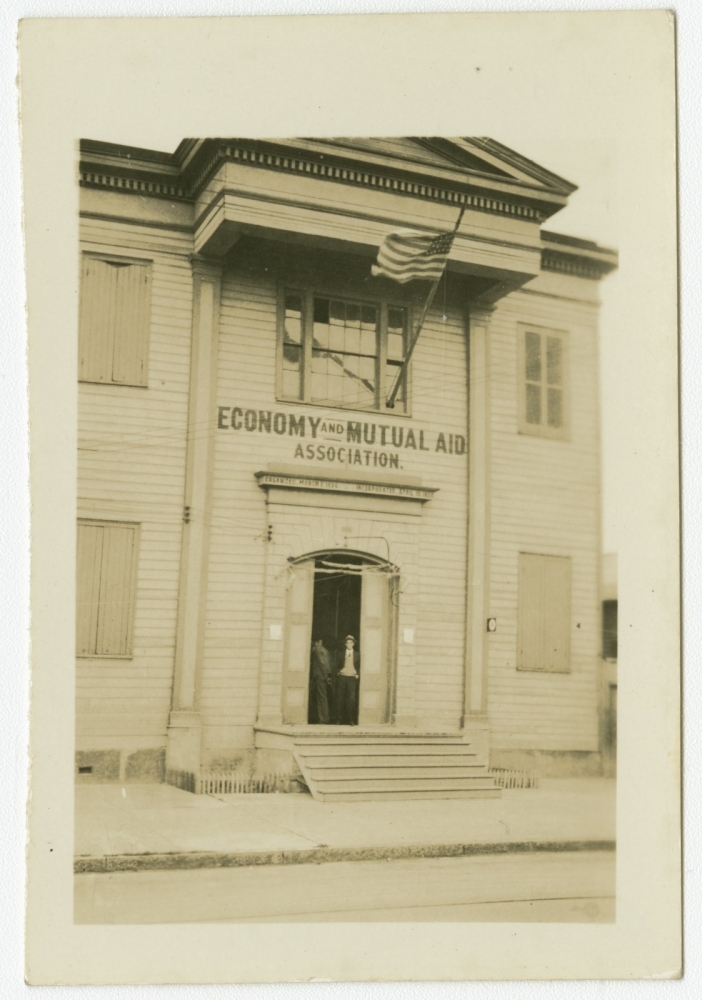

3. Economy Hall

Image taken in 1939 by Charles Edward Smith. (THNOC, 92-48-L.331.133)

Economy Hall was located at 1422–26 Ursulines Street. It was erected in 1857 as the home of the Société d’Economie et d’Assistance Mutuelle. Founded in the 1830s, the Economy Society (English translation) was a mutual aid organization for free men of color, and the building served as a meeting place for the important work of fighting for equality from before the Civil War through Reconstruction and the Jim Crow period.

According to Fatima Shaik, author of Economy Hall: The Hidden History of a Free Black Brotherhood, member William Belley designed the building, which included a large meeting hall, a ballroom with tongue-and-groove floorboards, a ladies’ dressing parlor, and a 70-foot-long theater. By the time it was destroyed by Hurricane Betsy in 1965, Economy Hall was remembered mainly as a site where early jazz greats such as Kid Ory, Harold Dejan, George Lewis, and Louis Armstrong had performed.

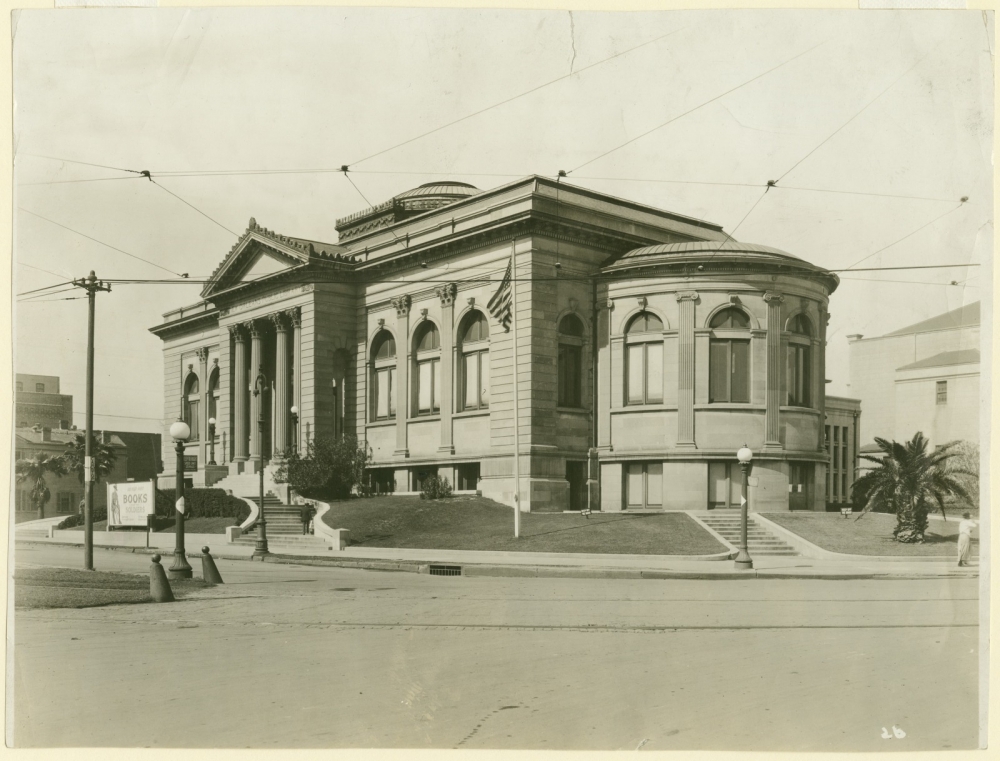

4. Original Main Public Library

Image taken in 1917 or '18. (THNOC, 1978.94.3)

The old main branch of the New Orleans Public Library in the 1000 block of St. Charles Avenue at Lee Circle was one of 2,509 libraries built in the United States between 1883 and 1929 with money donated by businessman Andrew Carnegie. It was one of six of these so-called “Carnegie libraries” in New Orleans. The Jefferson Construction Company, adhering to plans drawn up by architecture firm Diboll, Owen, and Goldstein, finished construction in April 1908, and the library opened to white patrons only later that year. African Americans did not have access to a library in the city until a branch for Black patrons opened on Dryades Street in 1915, and it was only in 1954 with the impending Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision that libraries in the city finally integrated.

The old main branch closed in 1958 and was demolished in 1959, when a new main branch on Loyola Avenue opened. Later that year the city sold the Lee Circle property, on which John Hancock Mutual and Life Insurance Co. built a seven-story, 60,000-square-foot office building. John Hancock subsequently sold that property to K&B in 1974, and 1055 St. Charles Avenue, where the stalwart old main library once stood, was henceforth known as K&B Plaza.

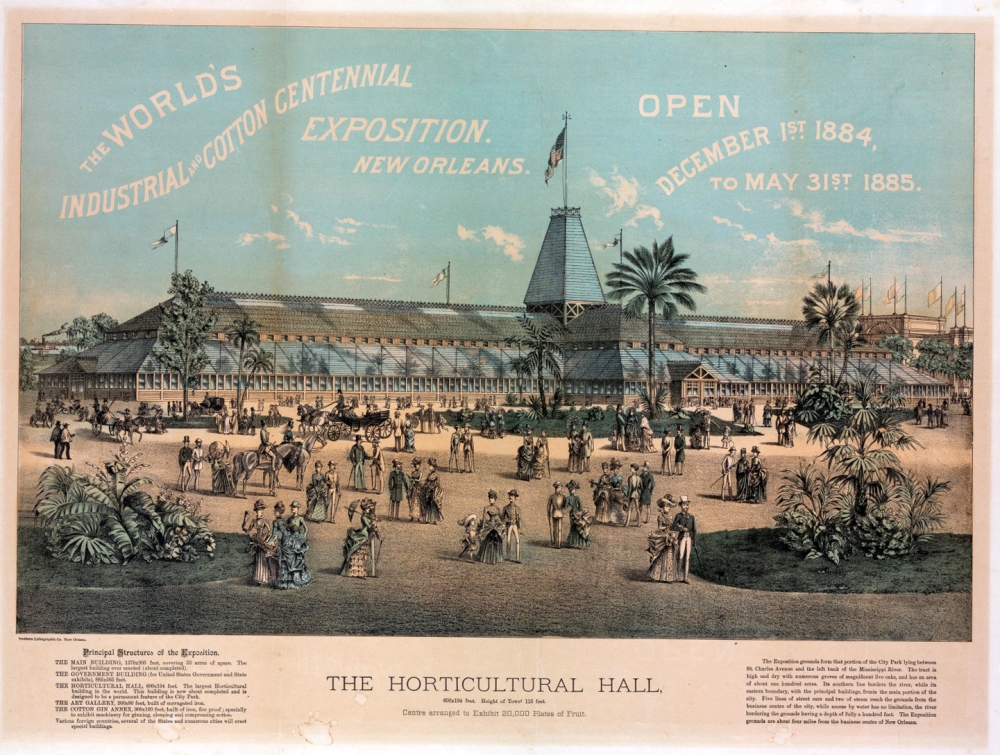

5. Horticultural Hall

Lithograph created in 1884 by the Southern Lithographic Company. (THNOC, 1957.40)

Horticultural Hall, a massive greenhouse built to house a collection of rare tropical plants, was one of the most distinctive and longest-surviving buildings from the 1884–85 World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition held in what is now Audubon Park. Arthur E. Rendle of New York designed the wood and glass building which was constructed using his family’s patented glazing system. The structure covered the combined lengths of two football fields. At its center, a 90-foot tower rose over an indoor fountain.

In September 1909, a tornado destroyed much of the structure, which was only partially repaired. In March 1915, the Audubon Park Commission closed the attraction and targeted it for demolition. The move inspired public outcry, but just six months later, the hall collapsed entirely during the major hurricane that struck New Orleans on September 29, 1915. Plans to rebuild Horticultural Hall never materialized.

6. Southern Railway Terminal

Image taken in the 1930s. (Charles L. Franck Studio Collection at THNOC, 1979.325.6113)

The Southern Railway Terminal at Canal and Basin Streets served as the main train station for the city from 1908 until it was demolished in 1955. The majestic Beaux-Arts structure was designed by Daniel Burnham, the renowned architect also known for the Flatiron Building in New York City and Union Station in Washington, DC. A large archway marked the building’s Canal Street façade, embellished by a towering grid of windows. Interior details included mosaic-tiled floors and a domed ceiling above the main room. Waiting rooms were segregated—one for white men, one for white women, and one for African American travelers.

For decades, the Southern Railway Terminal was an integral part of New Orleans’s access to the rest of the country, until the explosion of automobile and commercial air travel in the 1950s. Southern Railway Terminal was one of six train stations within New Orleans that were all eventually replaced with the New Orleans Union Passenger Terminal, which opened on Loyola Avenue in 1954 and is still in use today. The site of the Southern Railway Terminal is now the neutral ground next to the Saenger Theater, occupied by a statue of the South American leader Simón Bolívar. A recent NOLA.com article by Mike Scott provides a detailed look at the railway terminal and even shows a floor plan.

7. Old Ursuline Convent

Lithograph made in 1885 by T. Fitzwilliam & Co. (THNOC, 1987.37)

In 1824 the Ursuline nuns left their Chartres Street convent, built around 1750, and moved to a much larger complex in today’s Ninth Ward designed by architects Claude Gurlie and Joseph Guillot. It was an outpost of Old World Catholicism on the edge of an expanding and Americanizing city. The convent became a landmark along the river.

The complex spanned from its entrance on Dauphine Street to the levee, covering over six square city blocks, and included buildings for religious life, a boarding academy for girls, and an orphanage. School activities were conducted in French and English. In 1912 the 52 nuns in the cloistered convent moved upriver to the current location of Ursuline Academy on State Street, selling the North Peters Street convent, which was demolished to make way for the Industrial Canal in 1918.

8. Gilbert Academy and New Orleans University

Image created between 1920 and 1934. (Charles L. Franck Studio Collection at THNOC, 1979.325.1947)

This four-story structure at 5318 St. Charles Avenue, now the site of De La Salle High School, housed educational institutions for African American students from the late nineteenth to the mid-20th century. Built in 1888, it first served as the main building of New Orleans University, newly founded by the Methodist Episcopal Church with a mission to educate formerly enslaved African Americans. An octagonal Gothic tower graced the front façade, and the building’s mansard roof was lined with dormer windows interspersed with massive chimneys.

In addition to dormitories and classrooms, this impressive structure also housed a library, dining hall, museum, and chapel. In 1931, New Orleans University merged with Straight College and relocated to what is today the Dillard University campus in Gentilly. The building on St. Charles then became Gilbert Academy, a high school for African American boys. Many white Uptown residents did not want a school for Black children in such a prominent location and in 1949 pressured the Methodist Church to sell the property. In 1993, a plaque was placed on the corner of Valmont Street to educate passersby about the schools that came before De La Salle. For more information about New Orleans University and Gilbert Academy, see the Preservation Resource Center article written by Richard Campanella.

9. Old French Opera House

Hand-colored glass slide made between 1885 and 1900. (THNOC, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Elvert M. Cormack, 1981.290.34)

Designed by James Gallier Jr. and Richard Esterbrook and opening in 1859 at the corner of Bourbon and Toulouse Streets, the imposing and luxurious structure was a premier (and premiere) venue for music until fire destroyed it in 1919. New Orleans’s love affair with opera dated to the 1790s (longer than any other city in the nation), and the French Opera House featured the best companies from here and abroad. Performances were attended by both whites and African Americans, though Black patrons were required to sit in substandard, segregated areas, a practice that was unsuccessfully challenged in the Jim Crow courts of the period.

Much more than an opera house, it was also the center of French-speaking social life, a place for balls, concerts, and gatherings of all sorts. Its demise signaled to many the end of an era and the final blow to French as an everyday spoken language in the city—but it also gave a fierce urgency to the city’s nascent historic preservation movement.

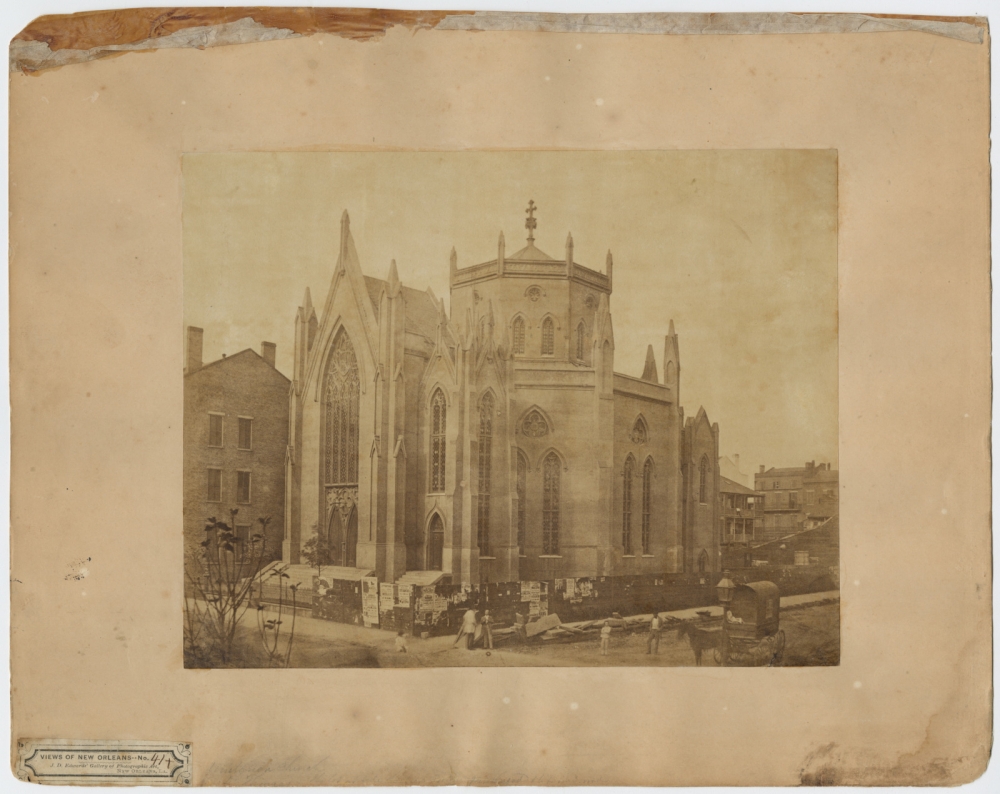

10. Church of the Messiah

Image taken between 1857 and 1861 by Jay Dearborn Edwards. (THNOC, 2009.0224.19)

The First Unitarian Universalist Church of New Orleans, founded by the Rev. Dr. Theodore Clapp, lost its initial home in a fire that also destroyed the St. Charles Hotel in 1851. The congregation hired architect John Barnett to design them a new home, to be built on the corner of St. Charles Avenue and Julia Street, which became known as the Church of the Messiah.

Barnett designed a lavish, Gothic Revival church with flying buttresses, a rectangular entry and chancel, and an octagonal sanctuary. Built between 1853 and 1855, the building did not last long in the New Orleans skyline. In 1893 the congregation, under the leadership of Pastor Walter C. Pierce, sold the church and moved uptown. Barnett’s church was torn down shortly after the sale to make way for a garden planned by neighboring property owner Joseph Hedwig.

11. Phillis Wheatley Elementary School

Image courtesy of the Southeastern Architectural Archive, Special Collections Division, Tulane University Libraries.

The original Phillis Wheatley Elementary School, named for the famous 18th-century poet, was built in 1954 as a segregated school for Black children at 2300 Dumaine Street in Tremé. Designed by Tulane architect Charles Colbert, it was an iconic example of modern architecture in New Orleans and one of about 30 public schools built in the 1950s. The cantilevered structure was held up by large concrete supports, which were inspired by flood-conscious regional designs and provided extra play space below the school.

The school operated for about 50 years and, thanks to its design, did not flood during Hurricane Katrina in 2005. It remained closed after the storm, however, and was demolished by the city in June 2011 despite pushback from community members, preservationists, and entities such as the New Orleans Historic District Landmarks Commission. A new school building was rebuilt on the same site and now operates under the same name.

12. “Touro Row”

Wood engraving by John William Orr in 1885. (THNOC, Gift of Boyd Cruise and Harold Schilke, 1959.157.5)

The Touro buildings, often called “Touro Row” and named after investor Judah Touro, were built between 1852 and 1856 and occupied one common façade on the 700 block of Canal Street between Bourbon and Royal Streets. Its most distinguishing feature was a continuous, 360-foot double gallery of lacy cast iron on the second floor, which wrapped around both corners of the building.

The four stories of Touro Row were home to stores selling dry goods, carpets, jewelry, and drugs, as well as musical instrument shops like Grunewald’s and Werlein’s. Most of the structure was destroyed in 1892, in one of the worst downtown fires since the colonial era. Three units near the corner of Royal and Canal street are still standing today, but the rest of the block has been replaced by newer structures, and the iron gallery is gone. Read more about the Touro buildings from Richard Campanella’s article for the PRC.

13. Second Masonic Temple

Image taken circa 1925. (Charles L. Franck Studio Collection at THNOC, 1979.325.375)

Famed New Orleans architect James Freret’s appreciation of Gothic architecture showed in his design of the Second Masonic Temple, a building that dominated the corner of St. Charles Avenue and Perdido Street but stood only briefly, from 1892 to 1922. Freret’s fantastical creation sported a corner turret with conical roof, pinnacle dormers, numerous Gothic windows, and an octagonal spire. Aside from the Grand Templar Hall, the building held libraries, meeting spaces for Mason chapters, offices for rent, and at one point, a Cadillac dealership on the ground floor.

The structure was plagued with problems from the roof to the foundation, however, and the constant need for repairs drove the Freemasons to tear down their iconic structure in the 1920s and erect a more modern mixed-use skyscraper. Next time you walk down St. Charles Avenue and pass Lüke restaurant, look up at the sky and think about what that block would be like if the Gothic monument were still around. Richard Campanella provides a detailed history of the Masonic Temple in an article for the PRC.

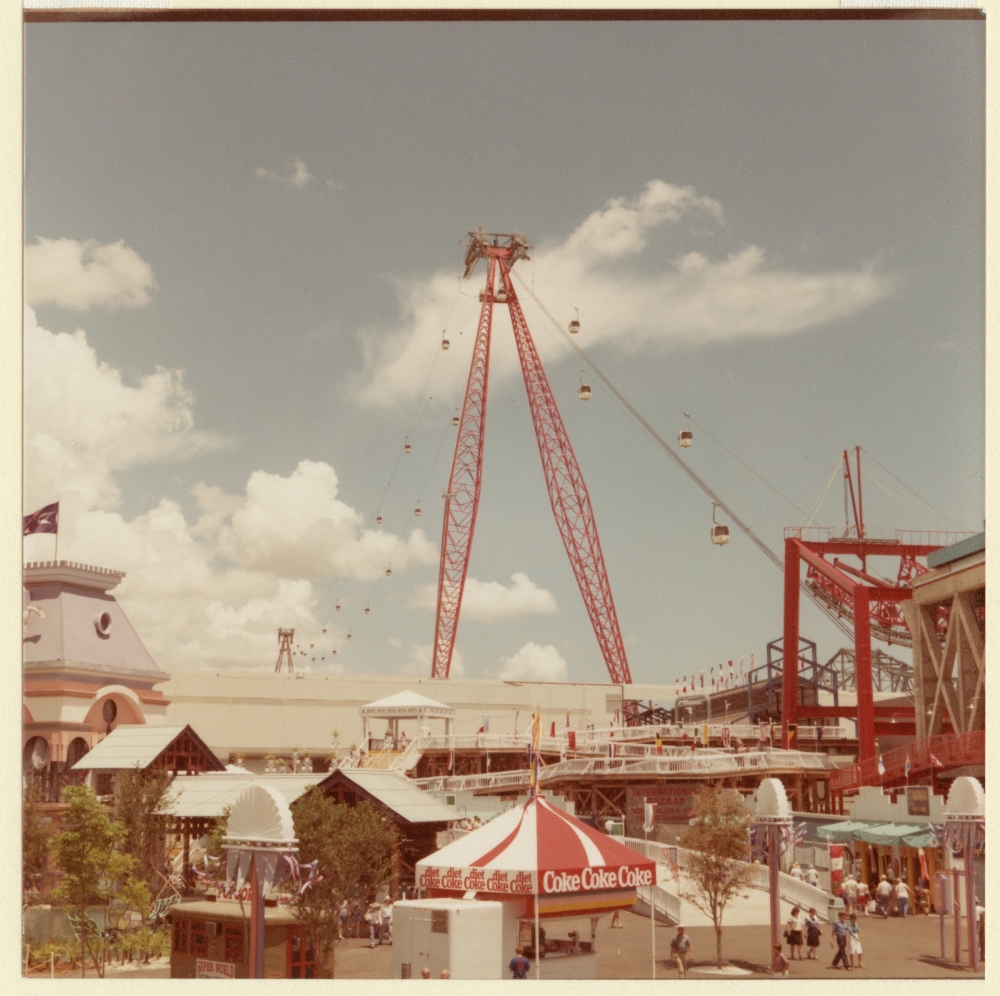

14. M.A.R.T. Gondolas

Image taken in 1984 by N. Thomas Cirar. (THNOC, 1985.33.23)

Two 360-foot steel towers used to stand on opposite sides of the Mississippi River, one planted near Blaine Kern’s Mardi Gras World in Algiers and the other next to the present-day Morial Convention Center. A steel cable connected the towers, carrying small pods called gondolas that ferried people to and from the 1984 Louisiana World Exposition. Soaring over the waterway, passengers of the Mississippi Aerial River Transport (MART) system could reach the other side of the river in under five minutes.

The MART’s designers, Kern and architect August Perez III, hoped that the cable cars would become a permanent transit option for commuters from the West Bank, but the ’84 Expo was a financial failure, and ridership never provided enough funds to make the system viable. The MART outlived the fair by only a few months. The steel towers, however, remained part of the city skyline until 1994, when the US Coast Guard ordered their removal. If you’re feeling nostalgic, you can visit the one gondola that’s grounded in front of Nesbit’s Poeyfarre Street Market in the Warehouse District.

15. The Moresque Building

Image taken in 1892 by James P. Craig. (THNOC, 1970.29.38)

Imagine lying in the grass of Lafayette Square listening to a band perform at Wednesdays at the Square with this exotic structure gracing the skyline. During the last quarter of the 19th century, the Moresque building filled the block bordering the block framed by St. Charles Avenue, Poydras, and Camp Streets. William A. Freret designed the building with his cousin James, and construction began in 1859 but was not completed until after the Civil War.

Called Moresque because of its Moorish design flourishes, the building’s façade was constructed of cast iron with an elaborate pattern of arches. The building was destroyed in a spectacular fire in 1897 that melted its iron frame. A Beaux Arts–style bank—now the Whitney Hotel—was eventually built on the corner of Poydras and Camp, and the Poydras Center office building takes up most of the rest of the block. Mike Smith described the rise and fall of the supposedly fireproof Moresque building for nola.com.

16. Jewish Orphans’ Home

Image taken in 1953. (Charles L. Franck Studio Collection at THNOC, 1979.325.361)

Architect Thomas Sully designed the Jewish Orphans’ Home that stood at St. Charles and Peters (later Jefferson) Avenues from 1887 to 1964. Built for the Association for the Relief of Jewish Widows and Orphans, the structure replaced a smaller facility on Jackson Avenue at Chippewa Street. When the orphanage closed in September 1946, about three dozen remaining children were placed in foster care or transferred to a Jewish orphanage out of state.

In 1948, the Jewish Community Center, formerly the Young Men’s and Young Women’s Hebrew Association, purchased the old asylum and the entire block it occupied; the group used the building until 1964, when it was razed to make way for the current Jewish Community Center.

About The Historic New Orleans Collection

Founded in 1966, The Historic New Orleans Collection is a museum, research center, and publisher dedicated to the stewardship of the history and culture of New Orleans and the Gulf South. Follow THNOC on Facebook or Instagram.