Editor's note: This story is excerpted from the new book Economy Hall: The Hidden History of a Free Black Brotherhood by Fatima Shaik. Learn more about the book, or order your copy, here.

"When you made Economy Hall, you was tops. It was just like you was playing at that big place . . . Carnegie Hall."

—Musician George “Pops” Foster, interviewed by historian William Russell, 1958

Untold thousands have gathered under the Economy Hall tent at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival to hear traditional local music, but how many have known the history behind the name?

Economy Hall was the English translation for the meeting place of la Société d’Economie, a mutual aid association founded by successful free people of color in 1836. By the 1890s, as racial oppression intensified, the Economie evolved from an elite to an inclusive society, and along the way nurtured a new, radical music called jazz.

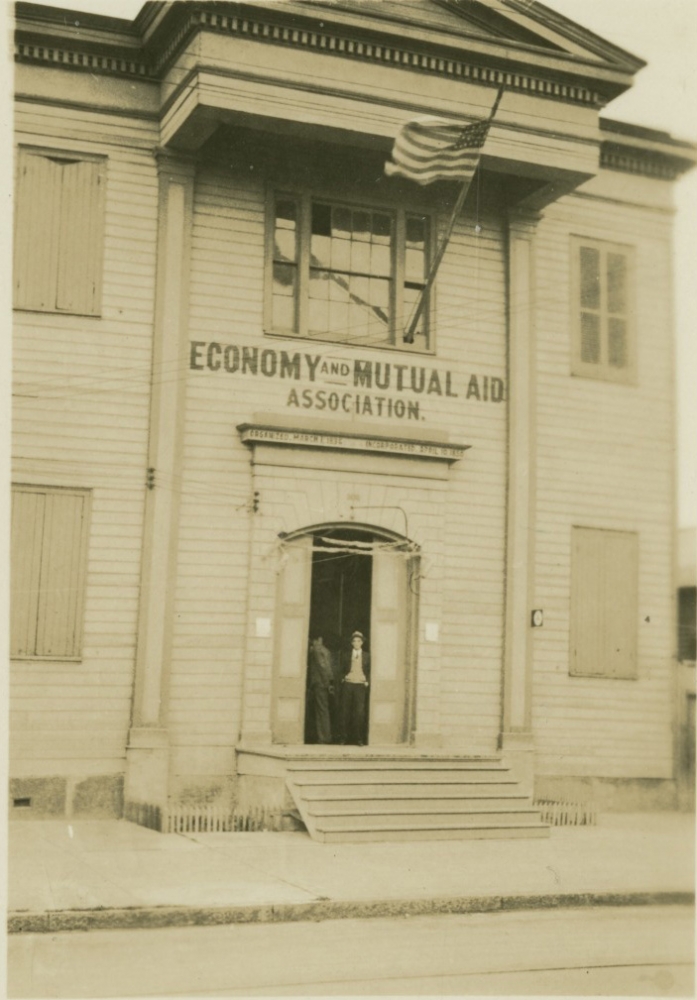

Economy Hall was the English translation for the meeting place of la Société d’Economie, a mutual aid association founded by successful free people of color in 1836. By the 1890s, as racial oppression intensified, the Economie evolved from an elite to an inclusive society, and along the way nurtured a new, radical music called jazz.

The music took hold in the society’s celebrations, convocations, and public balls. The Economie also rented their hall (inset) to other groups for parties, recitals, and performances. They celebrated defiantly, in spite of their segregated circumstances.

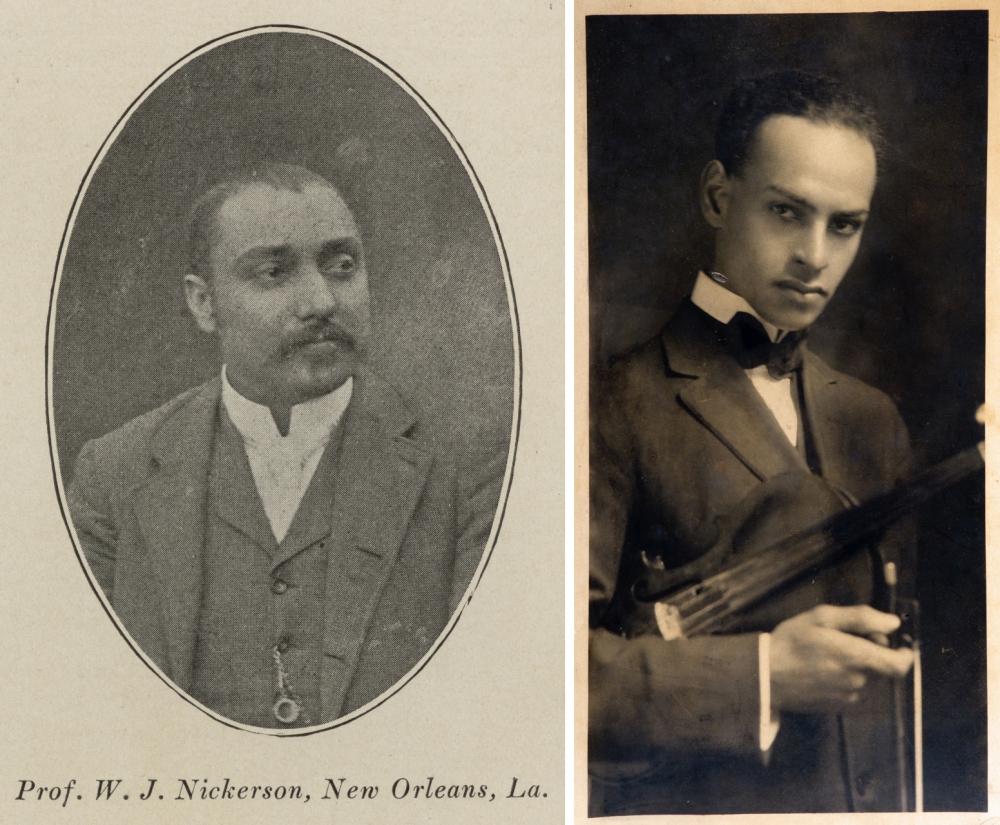

Members and entertainers mingled and were often related. The Eagle Brass Band had been the house band of the society’s functions since 1880. In addition, Economie member William J. Nickerson taught any number of musicians, including some of the earliest brass band players, to read compositions and score them. Myrtil Piron, the society president at the end of the nineteenth century, was from a family of musicians, and his nephew Armand became an orchestra leader whose song “I Wish I Could Shimmy Like My Sister Kate” took off across the nation.

Early musicians involved at the Economie included William J. Nickerson (left), who educated brass band musicians, and Armand Piron (right), who wrote the hit song “I Wish I Could Shimmy Like My Sister Kate.” (THNOC, 2017.0362; THNOC, partial gift of Priscilla and John Lawrence and Burt L. Barbre, 2009.0228)

Early musicians involved at the Economie included William J. Nickerson (left), who educated brass band musicians, and Armand Piron (right), who wrote the hit song “I Wish I Could Shimmy Like My Sister Kate.” (THNOC, 2017.0362; THNOC, partial gift of Priscilla and John Lawrence and Burt L. Barbre, 2009.0228)

As the doors closed on education and financial opportunities for the descendants of the former free people of color, many people of the new generation turned to careers as musicians. The first volunteer for the test case of the 1890 Separate Car Act by the Comité des Citoyens, Daniel Desdunes, was a member of the Creole Onward Brass Band. In 1891 the musician Charles Dupart lived at the same corner of Great Men and History Streets (present-day Dauphine and Kerlerec), where his ancestor of the same name had held the first Economie meeting.

Posters for balls in 1909 and 1910 name the Peerless and Imperial Orchestras, which included trombone player and Economiste (the term for a member of the Economie) George Filhe and drummer John Vigne, occasionally known as Jean. He was the brother of Economiste Léon Vignes. At least one hundred musicians mention Economy Hall in oral histories recorded as late as the 1970s and held in the Hogan Jazz Archive of Tulane University.

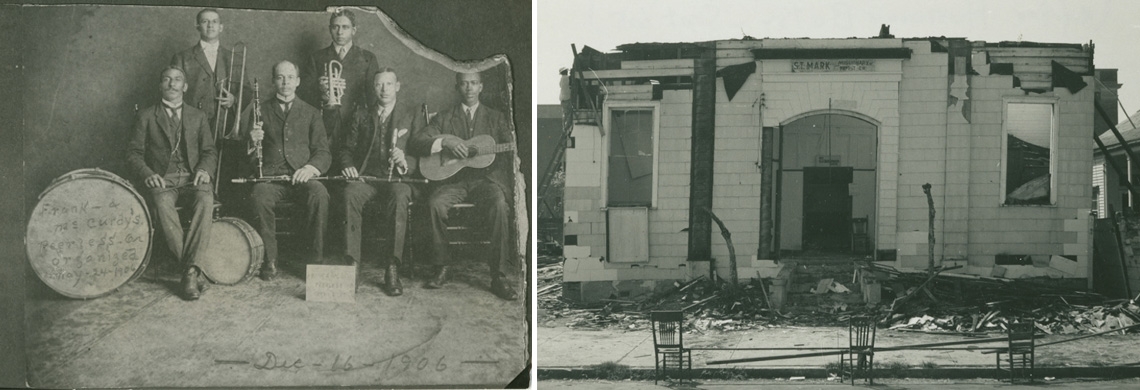

The Peerless and Imperial Orchestras played at 1909 and 1910 balls at Economy Hall. Peerless is pictured here with trombone player and Economiste George Filhe and drummer John Vigne. (THNOC, William Russell Jazz Collection, 92-48-L.331.2269)

The Peerless and Imperial Orchestras played at 1909 and 1910 balls at Economy Hall. Peerless is pictured here with trombone player and Economiste George Filhe and drummer John Vigne. (THNOC, William Russell Jazz Collection, 92-48-L.331.2269)

In 1958 bassist George “Pops” Foster told jazz historian William Russell, “Economy Hall was high class.” Foster was born in 1892 and played in New Orleans for many years. He described the sophistication of the early audiences, saying, “Whatever dance the people dance, you had to have the music to play that dance. . . . You got to play them waltzes. . . . You better play the waltz in the right tempo.” Otherwise, the dancers would notice the error and chide the band.

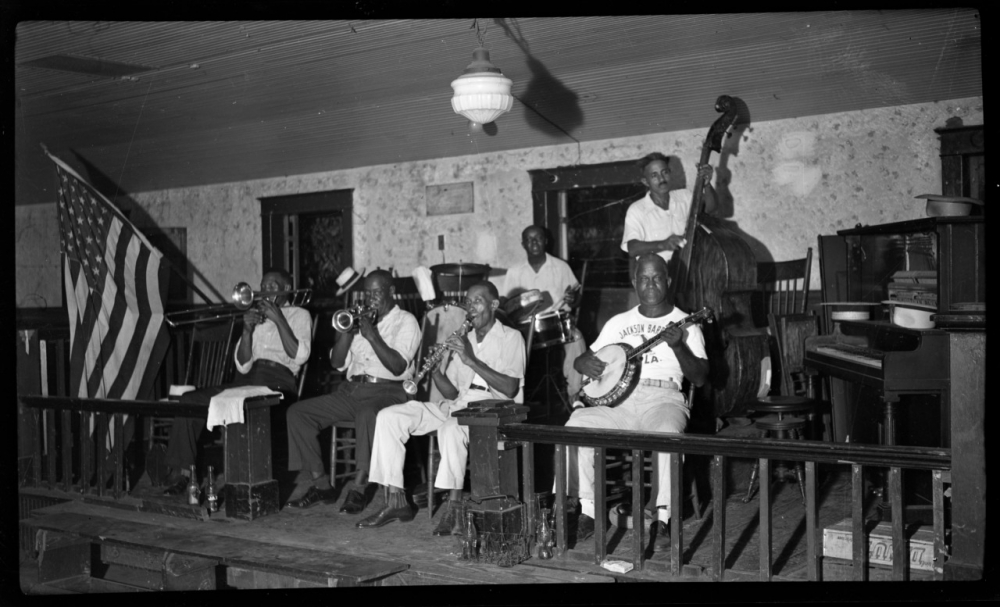

Clarinetist George Lewis—perhaps a descendant of Alcide Lewis, an Economiste who had volunteered for the Union Native Guards in the Civil War—recalled that at the Economie’s hall, the jazz bands played a special song when the club’s members made a regal entrance for their anniversary celebration, marching in two columns. The song was “The Gettysburg March,” though the historians who quote Lewis did not name the reason the band played this particular march, other than tradition.

George Lewis (seated, playing clarinet) is shown performing with a band at the San Jacinto, another important club hall in the city. Lewis recalled that the Economie’s members formally processed into their annual anniversary celebration. (THNOC, William Russell Jazz Collection, 92-48-L.331.307)

George Lewis (seated, playing clarinet) is shown performing with a band at the San Jacinto, another important club hall in the city. Lewis recalled that the Economie’s members formally processed into their annual anniversary celebration. (THNOC, William Russell Jazz Collection, 92-48-L.331.307)

The dance bands in Economy Hall infused marches and popular compositions with the syncopation of ragtime, the bent tones and vibrato of blues, and the enthusiasm of spirituals, as European musical traditions gave way to the vernacular of African descendants. These bands played the songs “ragged,” as if the musicians were happy drunks marching the street. The horns could also wail as if crying in a funeral procession. Sometimes, at the chorus, the performers hit the downbeat straight, as if they were stepping like soldiers. Other times they made the rhythm swing, reminiscent of beautiful young women waltzing across the Economie’s smooth wooden floor.

Early in his musical career, Louis Armstrong played in Economy Hall shortly before he was hired to play on an excursion riverboat on the Mississippi. People heard the music of New Orleans as it traveled upriver, not only with Armstrong but with so many others, to Memphis, St. Louis, and Chicago. It spread to New York and Los Angeles. The music was written about in books and picked up as a style, and it named the next decade—the Jazz Age.

Louis Armstrong (center) is shown with Joe “King” Oliver’s band in 1923 (Oliver pictured to Armstrong’s left). In 1918 and 1919, after Armstrong filled in for Oliver at gigs in Economy Hall and elsewhere, he was hired to perform on steamboat excursions on the Mississippi River.. (THNOC, William Russell Jazz Collection, 92-48-L.318)

Louis Armstrong (center) is shown with Joe “King” Oliver’s band in 1923 (Oliver pictured to Armstrong’s left). In 1918 and 1919, after Armstrong filled in for Oliver at gigs in Economy Hall and elsewhere, he was hired to perform on steamboat excursions on the Mississippi River.. (THNOC, William Russell Jazz Collection, 92-48-L.318)

Few people knew that jazz music had incubated in one of the most important venues for equality in the South, the Economie’s hall. They only recognized the democracy of jazz music, a style in which each performer played a different line in conversation with the others. It was as if each instrument told its own story, a personal story, and its individuality made the music better.

The audience heard the rough and spontaneous harmony without understanding that the songs came from the history of slavery and the struggle for suffrage, the irrationality of race prejudice, and the violence of its application. In jazz, someone was always pacing a little off beat or dancing around a note or sliding deliberately in and out of a musical line. Listeners didn’t know the path—because sometimes a new route had to be found individually in music and in life. In jazz, musicianship was just part of the sound.

A player with formal compositional training didn’t necessarily have an advantage over another who had strong improvisational leanings. It seemed that anyone could play jazz, everyone said. The music required training the ear to listen, the hands to avoid the easy, familiar notes. The heart of a jazz musician had to be open to the feelings of others. People sometimes wondered how this music came into being. They knew only that the sound was always alive.

The Economie had been defunct for decades by the time Hurricane Betsy destroyed the building in September 1965. The ruins are shown here in October of that year. (THNOC, William Russell Jazz Collection, 92-48-L.331.1268)

The Economie had been defunct for decades by the time Hurricane Betsy destroyed the building in September 1965. The ruins are shown here in October of that year. (THNOC, William Russell Jazz Collection, 92-48-L.331.1268)

In 1972 saxophonist Harold Dejan sat down for an interview with Roger Mitchell, a treasurer during the 1930s for the San Jacinto, another club that owned a dance hall. By the time they recorded their memories, the Economie had been defunct for decades, and the hall had been demolished seven years earlier.

The men did not remember anything specific about the organization that had owned Economy Hall, describing it only as “some benevolent to-do.” But they extolled the parties. Mitchell said, “I’m telling you, them was some wonderful days.”