Today, the term “filibuster” refers to the obstruction of legislative process through long speeches and other delay tactics. For most of the 19th century, however, filibusters were men who engaged in unsanctioned warfare in foreign countries—and a number of their campaigns were planned and set sail from New Orleans.

The word derives from the Dutch vrijbuiter, or freebooter. In the 1840s and ’50s, private armies of American filibusters frequently ventured to Latin America in pursuit of wealth, adventure, and fame. They often aligned their projects with political objectives, such as annexation of new territories and the expansion of slavery. The national press mythologized them, stirring up immense popular support, even though their expeditions might be at odds with federal authority. Presidents Zachary Taylor and Millard Fillmore, for instance, worried that filibuster expeditions undermined diplomatic objectives and the legitimacy of the American state. At the same time, filibusters were often the tip of the spear of American foreign policy.

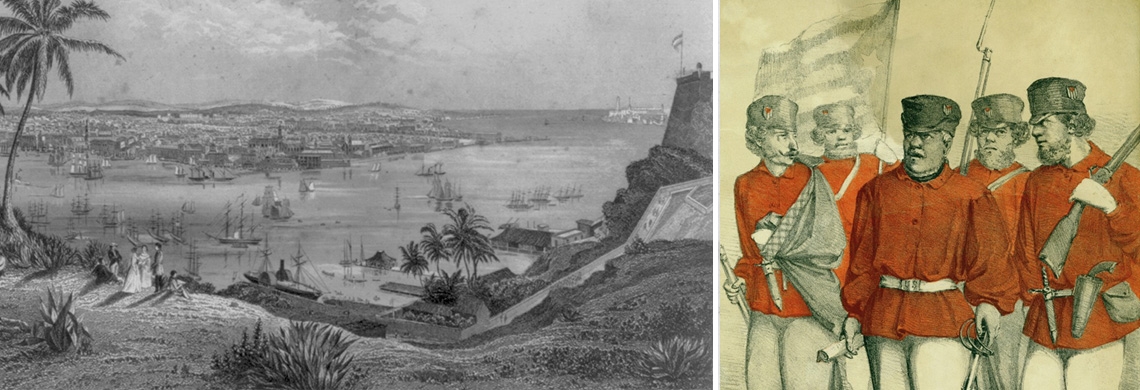

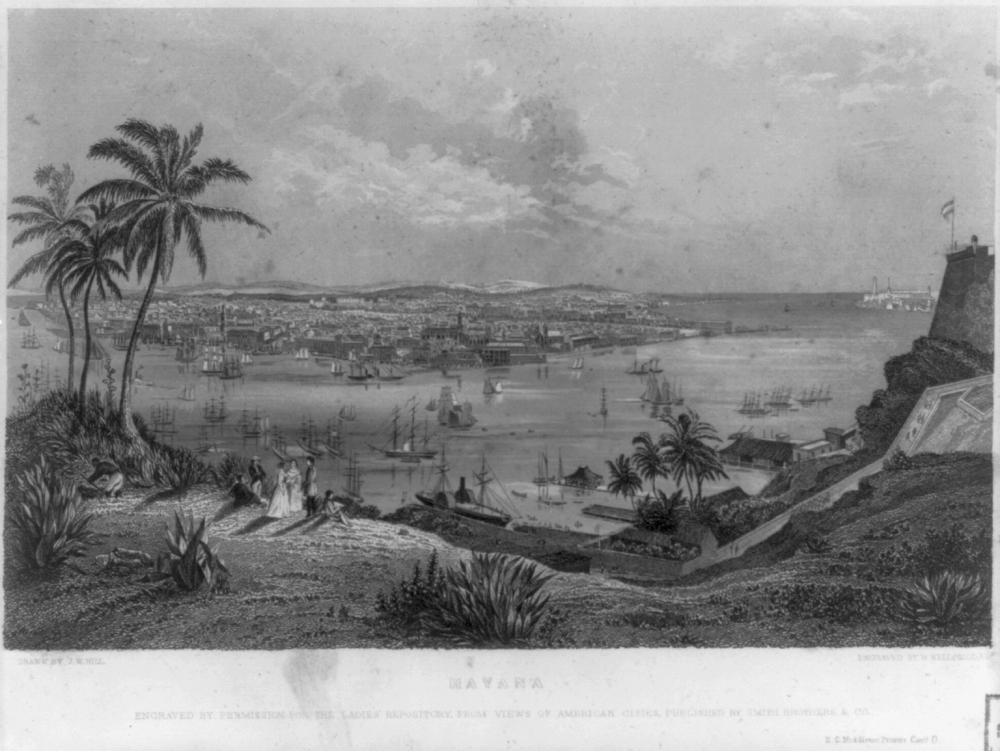

An 1850s watercolor by Marie Adrien Persac shows New Orleans around the time that Narciso López, a former general in the Spanish army, led expeditions to Cuba. (THNOC, acquisition made possible by the Clarisse Claiborne Grima Fund, 1988.9)

“Manifest destiny” is usually associated with the settlement of the American West. This popular doctrine of the 19th century, which held that the United States was uniquely positioned by Providence and civilizational superiority to expand its borders, was hemispheric in scope. Promoters of American expansion especially looked to Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean, where turbulent political conditions seemed favorable to foreign interventions.

New Orleans was a frequent staging ground for filibusters, in part because it hosted a sizable community of exiles from Latin America, including the former Spanish army general Narciso López.

López came from a wealthy family in Caracas, Venezuela. During the Venezuelan War of Independence, he fought for the Spanish Empire against the forces of Simón Bolívar. Following the defeat of Spain in 1823, López withdrew with the Spanish army to Cuba. He later saw combat in Spain, before returning to Cuba to assume a high-ranking military post—a post he would later lose following a change in leadership in 1843.

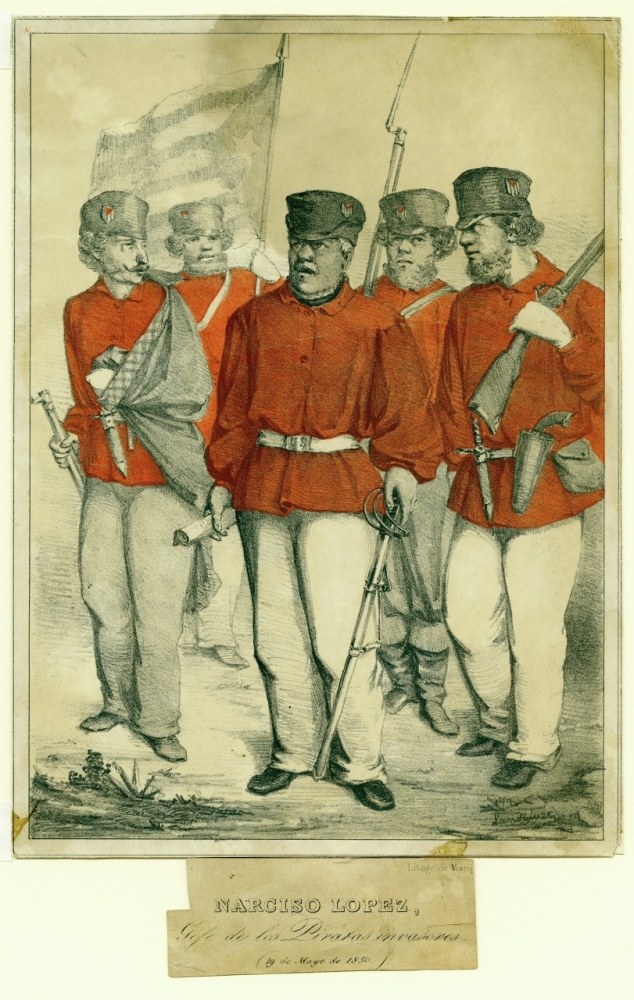

An 1850 lithograph depicts Narciso López’s expedition to Cuba to seize the island from Spain. The man in the rear is holding the modern-day Cuban flag, which López designed. (THNOC, 1978.123 a,b)

Over the next few years, López’s allegiances shifted. An anti-Spanish faction was on the rise in Cuba. Sugar planters and other members of the Cuban business establishment believed that the institution of slavery in Cuba was threatened by a weakening Spanish Empire. A group of these men formulated a plan to overthrow the Spanish government, followed by annexation of Cuba to the United States. López joined their conspiracy as military leader of the coup. The plot, however, was betrayed to the government, and in 1848 López fled Cuba to the United States, while a Spanish colonial court sentenced him to death in absentia.

From the US, López organized four military expeditions to Cuba. First, he sought financial backing in New York from Cuban exiles and American businessmen such as steamship magnates and sugar traders. His activities were championed in the press by advocates of American expansion, including the newspaper editor John O’Sullivan, who coined the term “manifest destiny.”

The first two expeditions were halted by federal intervention. With his Cuban backers losing faith, López relocated his headquarters to New Orleans, where he hoped to entice the Southern establishment to his cause. Planters and other members of the elite had interest in Cuba’s becoming a slave state, in order to tip the balance of political power in favor of the South.

López raised $50,000 in bonds and recruited 500 soldiers. In May of 1850, the company embarked for Cuba. They captured the coastal city of Cárdenas, less than a hundred miles east of Havana, hoisting the expeditionary banner sewn in New Orleans that symbolized American statehood for Cuba. In 1902 this banner was adopted as the national flag, and it remains the flag of Cuba to the present day.

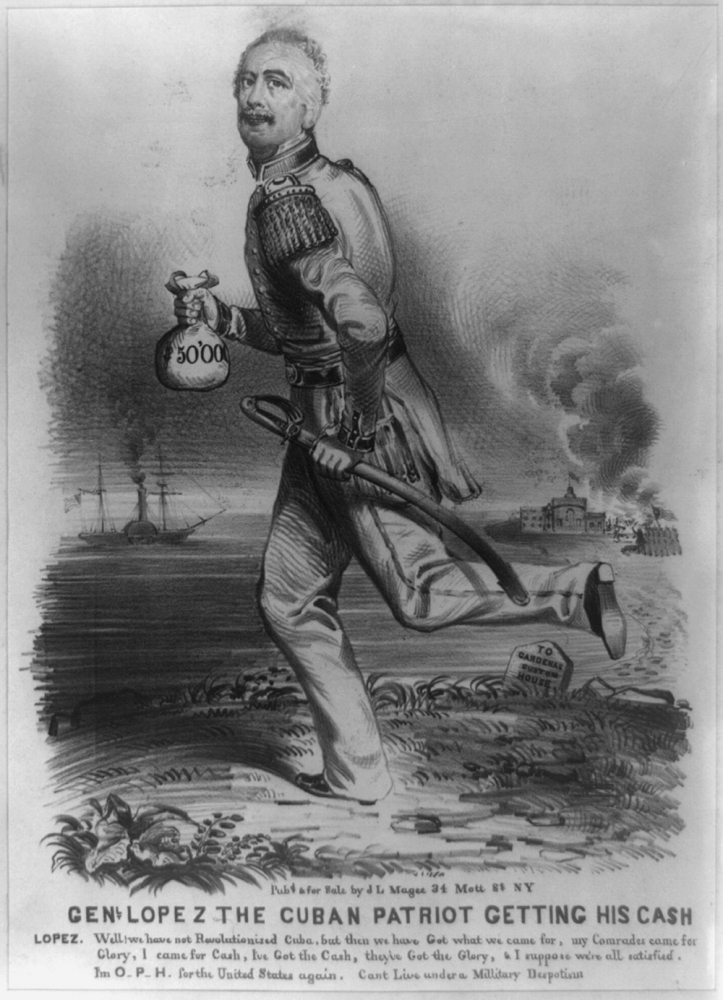

A satirical print made after López’s 1850 expedition depicts him making off with a bag of money stolen from the customhouse in Cárdenas, Cuba. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

A satirical print made after López’s 1850 expedition depicts him making off with a bag of money stolen from the customhouse in Cárdenas, Cuba. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

The Spanish army eventually overpowered the rebels at Cárdenas. Upon returning to American soil, López was arrested for violating the Neutrality Act of 1794, though the prosecution would soon be abandoned. Undeterred, he launched another Cuban expedition in August 1851. After making landfall near the town of Matanzas, López led about 280 soldiers inland, while about 120 men remained at the ships under the command of former US Army officer William Crittenden.

Spanish forces swiftly crushed both regiments. The local Cuban support Lopez had counted on failed to materialize. López, Crittenden, and 50 Americans were executed in Havana. News of their deaths set off riots in New Orleans. Mobs stormed the offices of the Spanish-language newspaper and attacked the Spanish consulate and other Spanish-owned property.

An 1850s print shows the port of Havana, Cuba. Narciso López, William Crittenden, and 50 Americans were executed after a failed attempt to overthrow Spanish authorities. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Despite its failure, the López expedition inspired later, even more ambitious filibusters in Latin America. The most sensational expedition of the era was perhaps the invasion of Nicaragua by American lawyer and journalist William Walker. After a years-long campaign, Walker managed to install himself briefly as president of Nicaragua, before his defeat in 1857 by a coalition of Central American forces assisted by the US Navy.

A version of this story appeared in the Historically Speaking column of the New Orleans Advocate.