In September 1812, French consul Louis Tousard penned a letter from New Orleans that described a devastating storm in alarming detail: “during the night a hurricane more horrible than any event, that even the oldest among us could remember, destroyed all the construction in the harbor; knocked down buildings; and took roofs from nearly all the houses in the city.”

A circa 1821 print depicts New Orleans’s Faubourg St. Marie, now known as the Central Business District. At the time of the 1812 hurricane, the city was a diverse mix of French- and English-speaking people of different races. (THNOC, the L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1937.2.3)

The letter, found in the holdings of The Historic New Orleans Collection, corroborates the research of University of South Carolina geographer and climatologist Cary Mock, who meticulously studied the track and intensity of the storm known as the Great Hurricane of August 1812. Katrina may be the hurricane that many New Orleanians consider the most devastating, but the one Tousard chronicles seems to rival it in magnitude. Could this 200-year-old storm have been even worse?

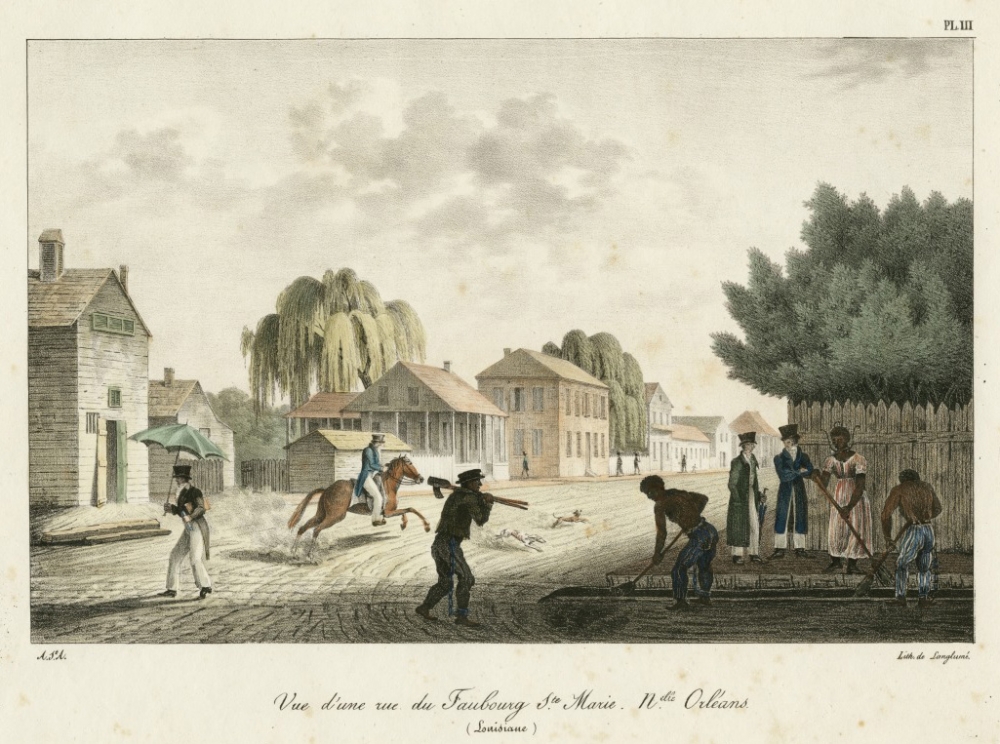

An 1816 map, made four years after the hurricane, shows the city of New Orleans. A blue line indicates the extent of flooding that took place after an 1816 levee breach upriver. In his letter, Tousard noted that the waters of the river and lake converged. (THNOC, the L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1945.3)

The storm occurred during a busy period for the residents of the newly minted state of Louisiana. Earlier in the year, a number of earthquakes along the New Madrid Fault Line caused levee breaches along the Mississippi, which required repairs. That summer, in three separate instances, enslaved people in the region rebelled against their condition, causing much concern among the local elite. Moreover, with the advent of the War of 1812 that June, British ships began to menace the Louisiana coastline.

Until recently, historians knew that a major storm had occurred that summer, but they knew nothing of its intensity nor the path that it took. Perhaps the hurricane’s power, the devastation it caused, and the lives it took were overshadowed by the focus on the war with the British that threatened to seriously disrupt lives and livelihoods.

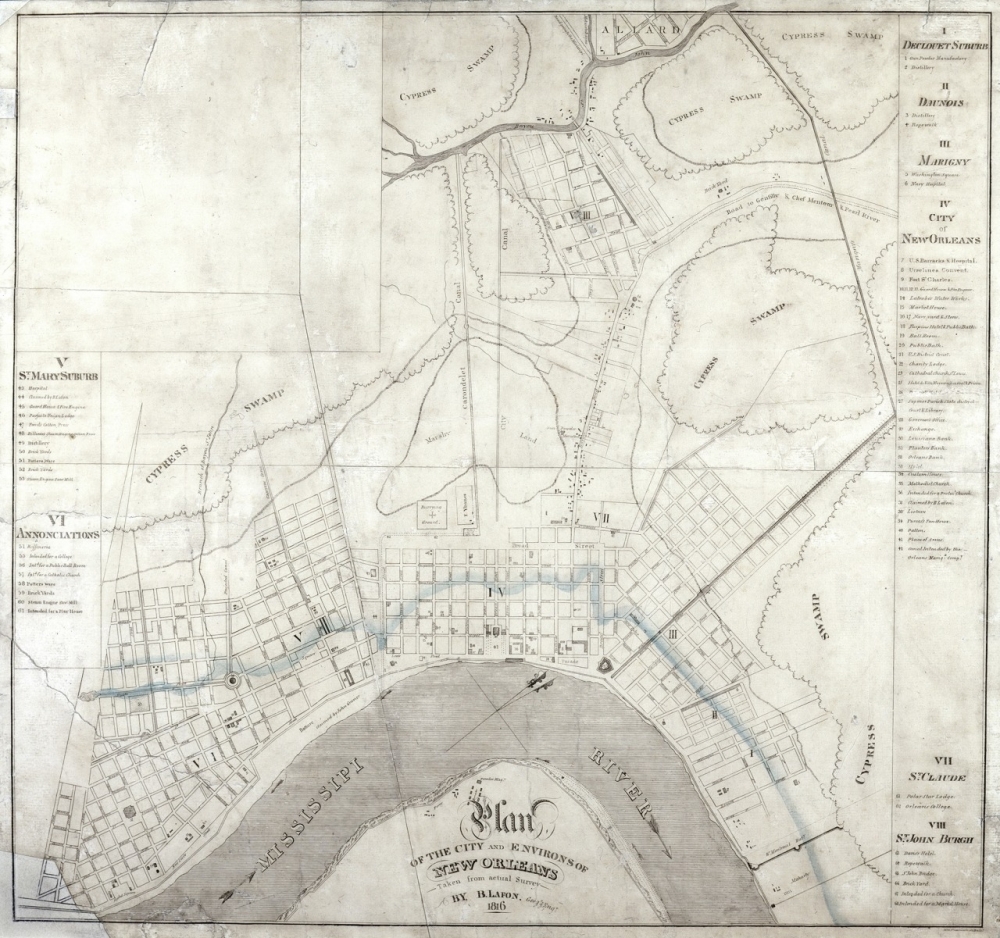

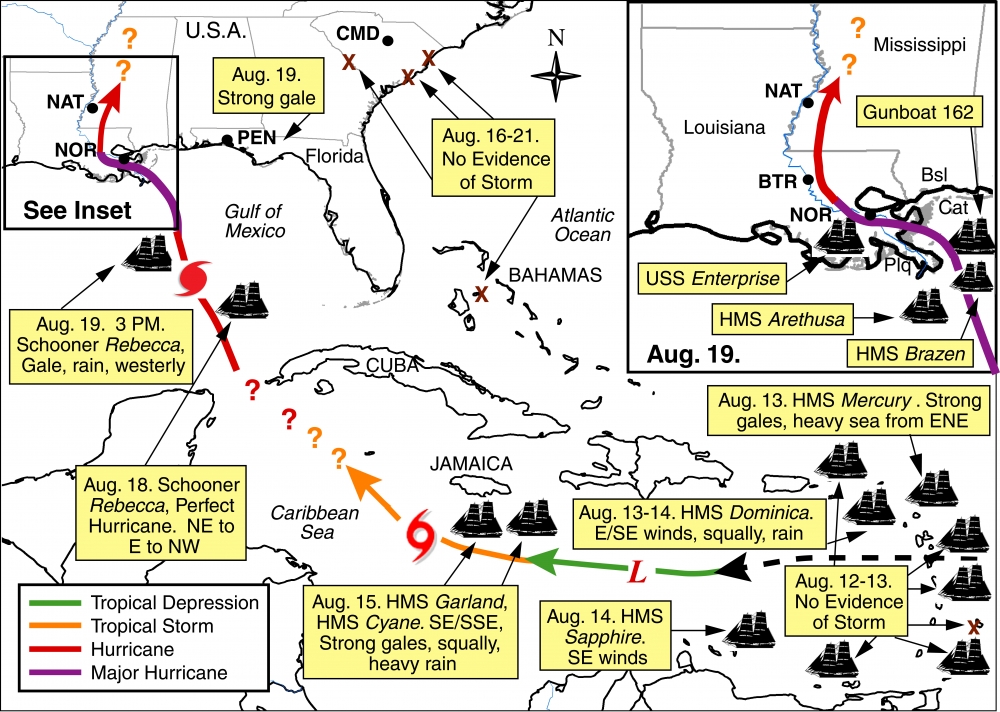

Because of the war, an unusually large number of ships plied the Gulf of Mexico and the nearby Caribbean. Many recorded hourly data regarding barometric pressure, wind strength, and wind direction that afforded Mock and his fellow researchers an extraordinary amount of information, which they used to recreate the storm’s course as well as to estimate its power. As part of a bigger National Science Foundation–funded project to research all tropical cyclones back to the late 1700s, they drew data and historical context from numerous newspapers, diaries, ship logbooks, and ship accident reports from the New Orleans Notarial Archives.

This 1813 image of a Corsair shipped named Alligator, shows the type of warship that would have been collecting data during the storm. Because of the War of 1812, an unusually large number of ships sailed in the area, giving modern-day researchers critical data to reconstruct the storm. (THNOC, The L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1939.7)

Fortuitously for Mock’s later research, the USS Enterprise, blockaded at New Orleans, provided particularly detailed wind observations in the city. Mock states in his 2010 article for the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society that “A change in winds to the southwest round local midnight suggests that the storm center passed to the west of New Orleans.”

Alas, that westerly track proved to be catastrophic.

A map from the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society shows the track of the storm, according to Cary Mock and other climatologists who studied data on the August 1812 hurricane. (via Mock, C.J., M. Chenoweth, I. Altamirano , M.D. Rodgers, and R. García-Herrera. “The Great New Orleans Hurricane of 1812.” Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 91: 1653–1663.)

Tousard provides an ominous description: “near the river’s banks the water of Lake Pontchartrain competed with those of the Mississippi to cover residences in over 10 feet, destroying men, homes, and animals.”

In 2010, Mock assessed the hurricane to be “at least a Category 3.”Today, with the addition of further data and the inclusion of Tousard’s account—which describes a clear overflowing of Lake Pontchartrain, foreshadowing Katrina’s flooding—he now believes it was likely a Category 4. Further, he contends that the 1812 hurricane, though probably smaller than Katrina in size, had a stronger wind field, strong enough to create a 10-foot storm surge, thus producing harsher conditions than more recent hurricanes such as Betsy and Katrina.

A street sign is submerged under floodwaters from Hurricane Betsy in 1965. Climatologist Cary Mock contends that the flooding of the August 1812 hurricane may have been worse than either Hurricanes Betsy or Katrina. (THNOC, 1974.25.11.75)

Characterizing the 1812 hurricane as “the worst-case scenario,” Mock’s analysis reminds us that we are vulnerable; he believes that it will eventually happen again.

His warning mirrors the dire final message in Tousard’s 200-year-old letter: “And, do note, that without a word of exaggeration, I add that had this scourge endured just two hours longer, I assure you there would remain not a soul to tell the tale.”