My family is from the Seventh and Sixth Wards, so I shared the best of two worlds. For a short period, I went to school at William O. Rogers before my family bought a house in New Orleans East. I always desired to come back to the neighborhood because that’s where all my friends were at. I came back so much, I slept over with my friends’ houses to keep me from riding the bus late at night. On the weekend, we liked to follow the bands around the neighborhood that came out for parades. I was a sideliner, and thought, “I'd like to do that one day.”

I got a break to participate in a second line parade from Mr. Wardell Lewis, who is the founder of a club uptown called Nkrumah Better Boys. It’s usually a friend who is going to pull you into a club. Recruit you. “Man, I like the way y’all look!”

“Yeah? Well, come down to the meeting one Sunday evening.”

You feel them out: Are the people in the club friendly? Are they stuck up? When you find people who are down to earth, you’ll feel home. I wanted to find out the ins and outer workings of a club, and Mr. Wardell taught me that. Once you get started with the music, the beat takes over you. You be so thrilled.

The Better Boys wanted to recruit small kids to catch some of this culture, too. I said, “You know what? I got my baby boy I want to put in the club.” I brought my wife Sue’s son, Askia, into it. He was three years old dressed up like one of us. He was a smash hit because he always had rhythm—all eyes on him; they done forgot about us.

When we paraded uptown, I got the little slack from different ones from my old neighborhood: “Oh, you don’t wanna be downtown; you wanna be uptown!” After five years, I talked to Sue and said, “You know what? I like our club uptown, but I kind of like it down here because this is where I'm from.” We started the Ole & Nu Style Fellas in April of 1997 with family and friends. Our first theme was “Getting Over the Hump” to celebrate getting the club off the ground. The camel was our symbol, and we wore brown and beige. All this time, the club has stayed in our family. We tried to do a lady thing, but it didn’t work out well, so we broke it down to just keeping the men, the children, and my wife. Sue is the only lady, matter of fact!

I met Sue at Charity Hospital, where I worked at for 18 years, and she worked for 33. She was living in the Lafitte Project taking care of her mom, Ms. Emelda Franks, and I moved in with them. The bricks were nice, but they were deteriorating—the plumbing and wiring needed to be upgraded. Sometimes we’d be in the dark. The electrical box next door got tampered with so now the whole building is out. We eventually bought our own little house, renovated it, and we live right here in the Sixth Ward around the corner from where the Ole & Nu Style Fellas come out.

Pork Chop Man

Throughout my life, I’ve had side jobs to make money for my family. In the late 1980s, my dad got me into being what you call a valet for Mardi Gras clubs like Bacchus, Endymion, Proteus, and Hermes. I assist the guys who ride on the floats, helping them into their costumes. I wear a black and white bow tie, white shirt, white jacket, black pants, black shoes—clean cut. They do all the basic stuff, and I’m going to help put on their cufflinks and other details. When I’m finished, I give the guy a mirror and say, “Look at yourself. You look very handsome tonight, you’re gonna kill ‘em dead!” They walk away and I call out, “Hold on, sir! Excuse me.” I straighten them out one more time. They’ll say, “I got you when I get back,” meaning they got my tip. Make pretty good money, too. Some guys will stick their wallet in my pocket and be like, “Take care of that till I come back.” They don’t want to get very drunk and lose it. Over the years, I worked my way from a regular valet man to being in the big room with the dukes, the kings, and all those people. Yeah, I dressed royalty.

In the early 1990s, after I got off work from Charity, I worked maintenance in condominiums in the Quarters. In 1993, I saw a guy on the street with a big box of incense. He was upset and wanted to throw them away. I said, “Man, don’t do that! I’ll give you a couple of dollars for them.” He gave me a box of incense with all kinds of flavors. I went home and told Sue, “Look what I got!”

She said, “What you gonna do with all that?

I said, “No, I got a brainstorm.” I took ten at a time, wrapped them up in aluminum foil, and set up a little stand by Joe’s Cozy Corner in Tremé.

After I sold all the incense, Kermit Ruffins, Charlie Brown from the Treme Sidewalk Steppers, and I had another brainstorm. I took the money I made off the incense, went to Winn Dixie, bought a red and black grill, bag of charcoal, fluid, a couple packs of smoked sausage, pork chops, some chicken, barbecue sauce, and four packs of bread. I brought it back to Joe’s, and all them big timers and high rollers would come by: “Wait, who’s selling that? You got that, D? That’s you?”

I said, “Yeah, what you want?”

Now, at every second line, I started to set up with my grill on the back of the truck. I had to get a bigger one because the business became so popular. The menu was hot dogs, hamburgers, turkey, chicken, smoked sausage, and pork chops. There was an ice chest full of water, cold drinks, juices, and a few beers. I had beer for me because I’m a beer man.

It went wild so I ran with that for a long time. The scene could get hectic. People got their hands up, money out, asking you to give them something, and you can’t go fast enough. I got to the point where I said, “I have to prep this ahead of time.” Sue and I learned to broil our chicken and smoked sausage at home because when you try to do it on the spot, you get overwhelmed by all the people. We can’t do that with the porkchops because that’s something you got to put directly on the grill. I had a pork chop made from Aucoin Hart Jewelers that I used to wear, and after that, my customers called me Pork Chop Man.

I was running around the city to the different stops on a second line with a grill on top of my truck. Inevitably, I had to interact with the police. They are directing traffic, and many times they can either let me go or stop me. An officer might say, “Where you going, man?”

“I am trying to get around that corner.” He’d say, “Come on.”

“I got something for you here,” and give him some grilled chicken. After a while, I got to know them.

There are only four or five stops on the parade, and many of them are barrooms. I parked on the corner down from the bar because the owners of the bar are paying taxes for the liquor license and have the overhead of running the bar. As a vendor, you aren’t doing that. There never was beef with me because I always gave respect. I believe in that: You give it, you get it. When I came by Joe’s Cozy Corner, Papa Joe already had a spot taped off for me because I hung out in his barroom. Showing love, as we call it.

Joe's Cozy Corner

My dad, Emile Peterson, grew up on North Rocheblave in the Seventh Ward. That’s where he came from—my grandmother’s house is there and everything. Some of our family is from Franklin, Louisiana, and we just found out recently we are part Choctaw Indian. Growing up, my grandmother spoke a little bit of Creole, but I didn’t understand it. When my dad was younger, he used to work for a fruit vendor in the French Market, and then moved on to construction. They call him Big Pants Pete because of the way he used to always be pulling up his pants. When I came by to see him on a Saturday, he asked me, “What we gonna do this evening?”

“Whatever you want to do, Dad.”

“We’ll go by Joe’s Cozy Corner, go by Candlelight, and the Vieux Carre on Basin Street.” We’d saddle up and make his little bar stops, which is what it’s all about in this neighborhood. You go bar hopping, one to the other: patronizing, spending a few dollars, walking down the street to the next one. When you see somebody you know, they’re gonna treat you: “Give Mr. Pete one.” My dad and Mr. Joe used to sit back, laughing and talking about the good old days when they worked in the construction field together. The Jolly Bunch parade was the club Mr. Joe and them had going on. My dad was with the Jolly Bunch one year, but he said he couldn’t do the whole walking thing, so he started riding in the car, looking good, and waving at people.

Joe’s Cozy Corner was Papa Joe’s pride and joy. On my way to work on Saturday mornings, I used to be the first person to pass by and shoot the breeze with him. He’d say, “D, go back behind the bar and get you one.” I liked cans of Budweiser and he always had bottle beer. Before I know it, I’d done drunk one sitting there talking with him while he’s stacking the boxes.

“I’m getting ready for these guys coming through here.”

“I hear you, Papa, I’m going to drink one more and get out of here.”

“Aw, man, get you another you ain’t got nowhere to be that fast.”

“Oh, Mr. Joe, I ain’t gonna be worth nothing when I get over to the Quarters messing with you!”

“You gonna be all right. You gonna make your money, but enjoy yourself, Darryl.”

After second line parades, I paid my crew off and said, “Look, we ‘re gonna go out and eat at Ruth Chris Steak House, and when we leave there, we gonna have drinks by Joe’s and catch Kermit before calling it an evening.”

Every Sunday night, people from all over the city came to Papa Joe’s to listen to Kermit Ruffins play. Sunday night was the night that you dress up, look good, and come out to have a few drinks. If you were already in there, and left, you couldn’t get back in because it was just full of people. Some kind of way, Papa Joe’s son, Lil Joe, found a seat for Sue at the bar. Sometimes it wound up being to the wee hours of the morning when we got home. I worked all day on this truck, I done drink them beers, laughed and joked and danced at the bar, and hated to see Monday coming. Why couldn’t I go to work for ten instead of seven? But it was a blast.

One night I said jokingly, “Hey, Kermit! Man, let me sing a little something.”

He said, “Ladies and gentlemen, we have a new starting out act tonight: Darryl ‘Pork Chop Man’ is in the house. He’s gonna come up here in a few minutes and give us a song.” I got speechless, and everybody looked at me, like, “Go ahead on!” The trombone player, Corey Henry, said, “C’mon, you got it, Pork Chop!” I sung an old Louis Armstrong song, “What a Wonderful World.”

I got everybody’s attention in this little place, and when I couldn’t remember the lyrics, Kermit filled in with the trumpet. That was a beautiful night there. Yes indeed, that little spot used to roll. For years, our parade disbanded at the bar because when the parade is over with, we still like to party more to talk about the good day we had—laugh and hug and enjoy each other. Say, “We did it again!”

In 2005, Mr. Joe shot Richard Gullette when he was selling beer outside his bar after Anthony “Tuba Fats” Lacen’s jazz funeral. Afterwards, Papa ended getting sick and was up there on the tenth floor of Charity Hospital. I worked for the state as a maintenance man, so I went up there and saw him lying there, not looking so good. I said, “Mr. Joe, just tell me something I like to know, Papa, why you did that?”

“Darryl, all my boys who come over to shoot the breeze with were out there, so I feel wrong for what I did, but when I went to confront the guy and we got into it, he hit me so hard it felt like a mule kicked me.” He said it was a moment of madness.

I said, “Wow, but didn’t you think, Mr. Joe, what would happen?”

He said, “Darryl, I knew I shouldn’t have, but I guess at that time, I just got caught up.”

I was there that evening. Sue and I still lived in the project because our house was being renovated. I came home and told her what happened. Our neighbor, who I greeted every morning and evening, came back crying. She said, “Joe just shot my daddy.” It was a real loss for everyone.

Reciprocity

Everybody’s got this special place they come out of when you have your second line parade. Most of the time, we start and break up at Ms. Jackie and George’s, a barroom on North Claiborne and Dumaine. That Sunday, you will feel like a superstar.

Our oldest son, Tyrone “Trouble” Miller, who is the president today, is a schoolteacher. He is also the designer and clothes man for our club. I don’t know how he can sit there and cut things out with the little blade he uses with the little measurements, but he can make anything.

One year we did the golf theme. We all wore knickerbocker shorts, little shirts that you wear with gloves, two tone shoes, the big apple hat, and clubs. When we kicked off by Seal’s Class Act, we called it “putting off” with the green turf, and had golf carts in our parade. Another year, we had boom boxes, televisions, and tape recorders. I did the fan thing uptown for years, so I like to have the umbrellas with Ole & Nu Style.

Everybody participates in making the decorations. The whole weekend leading up to that Sunday we have a little factory going on. We all do our part with the ripping and running. I’ve got to make sure the banners are done right, I got the rope people, I got the streamers. If we are decorating the barroom with balloons, I make sure the balloons are out at the right time.

You’re hyped but you don’t want to be sick, so you try to rest your nerves. I order a truck and a trailer to bring all the decorations because we change during the parade. We start with a nice casual outfit, and then we go to Seal’s and put on our Sunday best. Everybody wants to be there to see what we’re going to wear. It’s a lot of us trying to get everything together, and it can get tense.

Ms. Seal is a big friend of mine—we met when I was with the Better Boys, and we became like brother and sister. For years, she was an honorary member, helping to do functions with the club and riding in the car in the parade. You know how in school you’ll be waving your hand in class to get called on? When we started the Old & Nu Style Fellas, Seal was like that, “I wanna be the queen!” Her husband, Mr. Charles, is laid back and quiet. He always has her back and rode with her.

One winter, when I pulled out of the driveway of the Lafitte on my way to work at Charity, I kept seeing kids standing at the bus stop without coats. It bothered me so much one time, I took off my hoodie and gave it to a little boy. Afterwards, I told Sue, “We’ve got to do something for these children standing out there in the cold. We should do a coat drive.” Seal helped us sponsor the coat drive, and we’ve helped her each year with her Easter Sunday parade for the children. When my dad passed, she came to me and said, “I know your head is heavy and heart is full right now, but, Darryl, you know I got you, little brother, just let me know.” At Seal’s bar before the epidemic came up, on Sunday nights when Lisa Rae or any kind of live entertainment was there, it was packed. People would ask at the second line, “You going by Seal’s? Hold me a seat!”

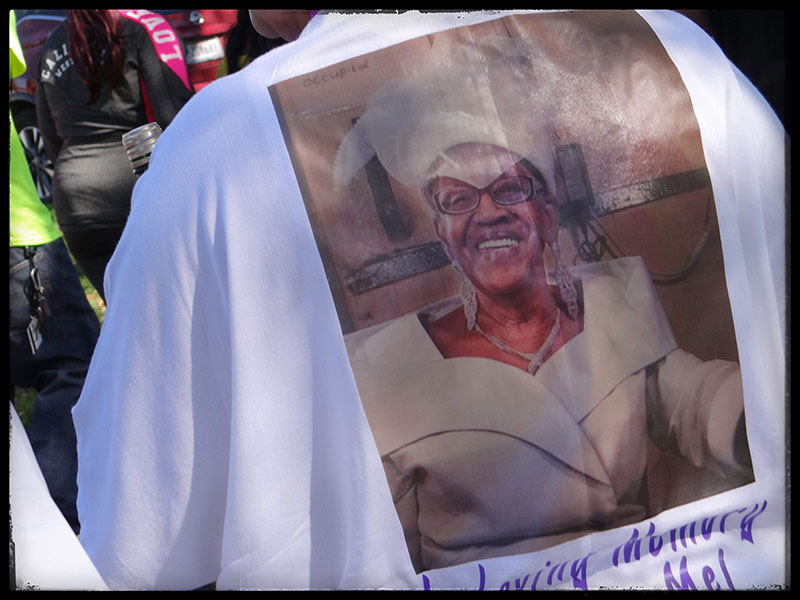

In the past, the king and the queen rode on a nice old school car, a convertible Mustang, or the horse and buggy. We wanted to keep it traditional so when my dad or my mother-in-law were in the parade, they rode in the horse and buggy from Mr. Charbonnet. Ms. Emelda Franks was the mother in the club.

One year, a good friend of ours who worked at the hospital was ready to be queen another year, but our king didn’t work out. Sue was panicking about it, and I said, “Don’t worry about it. I’ll be king, and we can lay it to rest.” I'm laying bed one night and came up with my theme: the white alligator. Mr. Wardell from the Better Boys designed my costume for me.

I rented two floats out of Kenner from a guy I used to work for in the Quarter—one for the queen and her court, and one for myself. I made a big round, blue and gold crown. On the float, two tall guys attached it to 20-foot poles with hooks, which they could hold up to clear the electrical wires running across the street. We thought we were prepared, but we didn’t do all our homework. A policeman came to me and said, “You know, this float is not going to clear every obstacle in this area.” I was good down Broad Street, but coming down Dumaine from my house, I couldn't make it. The police escorted my float down round Rampart to Canal, and over to Broad where I got back into the parade. It was so exciting because, to be honest, the only other social and pleasure club I ever knew that went down Canal was Zulu.

The policeman said, “I bet you didn’t think you would be coming out of world-famous Canal Street today, huh?”

I said, “I had no clue, whatsoever, officer!”

Another policeman told me, “It’s the last time cause we’re gonna make an ordinance. We’re not gonna have this problem no more.”