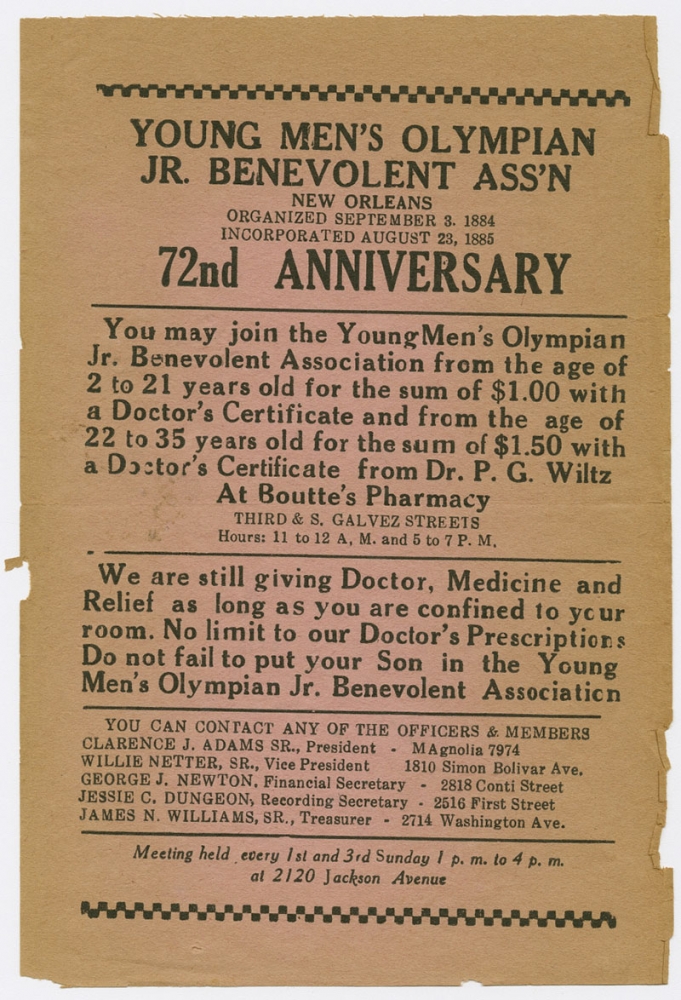

The Young Men Olympia Jr. are the second oldest benevolent society in the country. The only benevolent society that’s older than we are is the Firemen’s Benevolent Association. Our organization was started in about 1882 by African Americans who were very influential in the community—doctors, musicians, lawyers. They decided to come together to help the community because, at that time, African Americans were not afforded the opportunity to have health insurance and death policies. They came together to take care of the sick, get medications, and assist people with funerals. It became so popular that they decided to make it an organization and incorporated in 1884—that’s the anniversary date we celebrate.

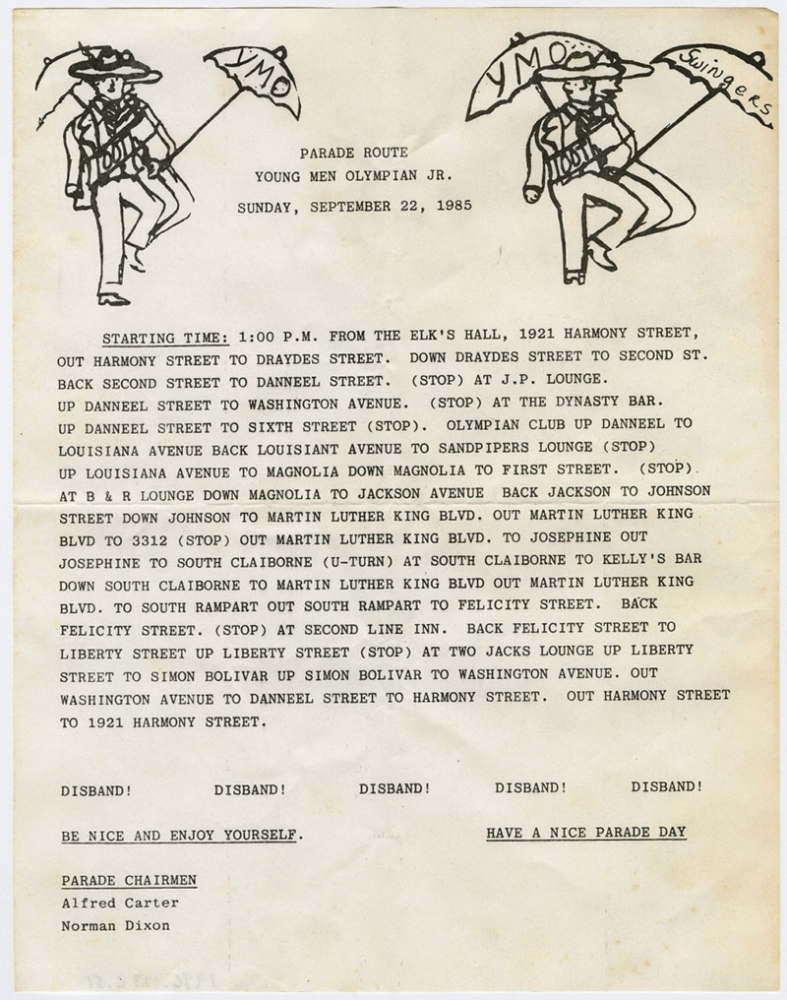

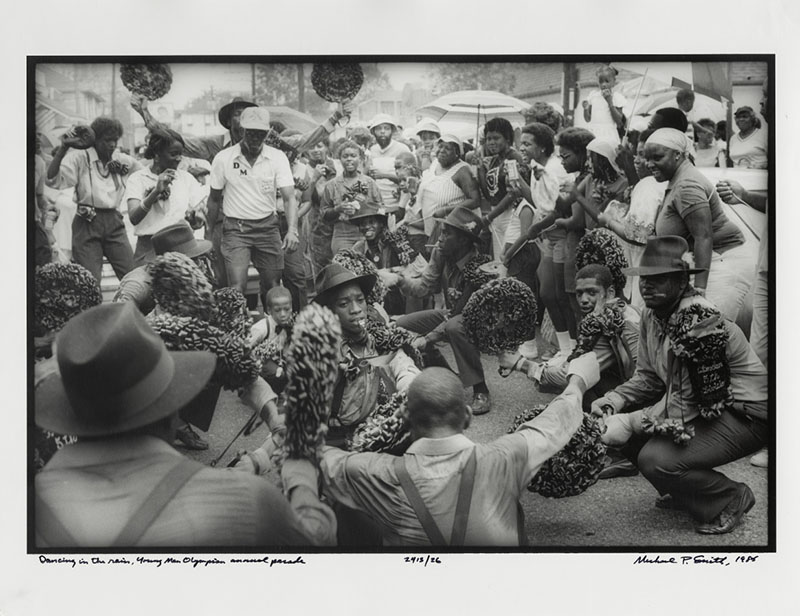

The original members met uptown on Jackson and First Street, and we’ve stayed uptown ever since. We have members from all over, including, after Katrina, several members in Texas. A lot of people call us a social and pleasure club but from our organization’s records, it was at least six years after our founding that we had a second line. The parade came out of the musicians who were in the organization. As they passed on and went to glory, other musicians formed a procession and marched them down to the cemetery. Sometimes people’s families have a resting place for them to go, but we also have two tombs in Lafayette No. 2 for any member who wants to go in there. It was one of the first nice, municipal cemeteries that African Americans were allowed to be buried in, so we jumped on it because it’s in the heart of our community. There are a couple of rules. Only members are allowed to go in the tombs, and there are no names allowed. It reads: “Young Men Olympics.” No individuals are named. Our reasoning is that everybody has the same value. Each time someone dies, it is equally the same loss to this organization.

As time went on, other members, who weren’t musicians, began to want a jazz funeral as well. The organization passed it where every member that died would have a procession with a band. Years went past, and nobody died so they didn’t have a reason to have a parade. Some of the members came together and brought it in front of the board that the organization should have an annual parade to celebrate anniversaries. Ten years later after the organization was formed, our annual parade began.

When I was younger, my dad and the older members would act like had you done hit them in the head with a hammer when the organization was called a “social and pleasure club.” But now I feel where they are coming from, because we do so much more than parade. Since I joined the organization in 1974, we have helped a lot of people who’ve been sick. We’ve buried a lot of people. Going through this pandemic, we’ve seen members come together and support each other even though we’re not allowed to parade. We had five members that were really sick in the ICU, and a couple of them were predicted to die, but God showed them grace. We were able to come together and be there for their families while they were in comas, locked in ICU. It made me really realize why I was able to go to college, get two degrees, come back, and still want to be a part of this.

Legacies

My dad, Norman Dixon Sr.’s involvement in parades began with his younger brother, Henrich. My dad was the second youngest of 16 brothers and sisters, and Henrich was the baby. Somehow Henrich became a member of the Jolly Bunch, and my dad used to follow him. I don’t know how Henrich got to that club downtown because he was an Uptown guy who went to Booker T. Washington Senior High. Later, he spent 15 years in jail for a crime he didn’t commit. After he was released, he graduated from SUNO as one of the state’s first African American social workers.

My dad went to Booker T. as well. He held three state scoring records in basketball. He had a 60-point night, a 55, and then another 60. When we were little boys, he brought my brother and me to the YMCA on Lee Circle to see his name in the records they had displayed. At the play-off game to go to the state championship, Booker T. played against Cohen where Alfred “Mr. Bucket” Carter and Mr. Steve Solomon were on the team. Mr. Bucket and them won the game. My dad found out about the Young Men Olympics through his friendships with them.

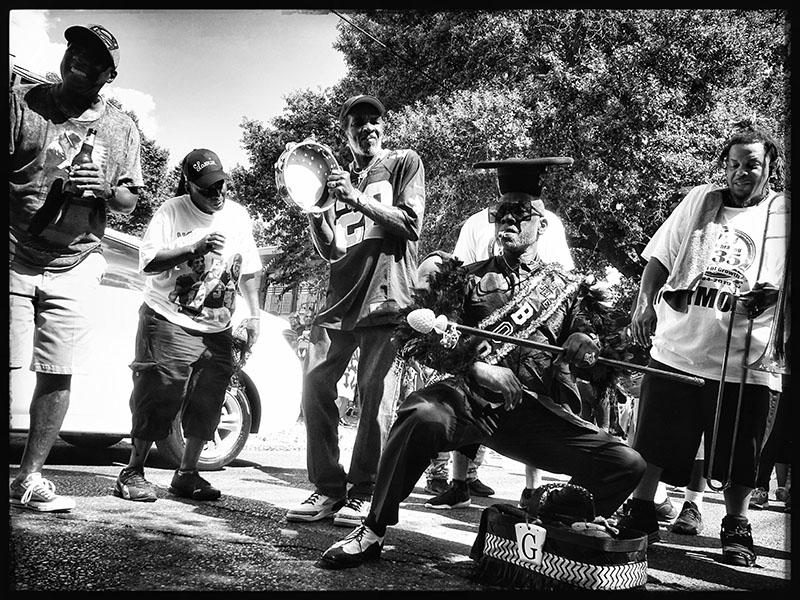

Mr. Bucket joined the organization when he was five years old, and he never missed a year. He came in with Mr. Steve and Mr. Johnny Sanders. It would be so hilarious to hear them talk about who was in first. Bucket used to tell everybody he was the longest member here, and then Mr. Johnny would walk up and say, “I remember when you joined. I was sitting on the first row.” At that time, you couldn’t join until you were five. Mr. Johnny’s birthday was in October, and Mr. Bucket’s was in November. But it didn’t stop there because Mr. Steve was born two months ahead of both of them. All of them were still here in their 80s. They died within two years of each other.

When my dad found out about the organization, he said he was drawn to this brotherhood. He joined when he was about 18. And I can tell you this, every male that’s in my family since has had an opportunity to at least get in it and test it out.

I was born Uptown. When I was four, we moved across the river to lower Algiers. There were three families that lived in the Cutoff: The Greens, the Rosses, and the Bens. It was like one big family. During Mardi Gras, the Krewe of NOMTOC (New Orleans Most Talked of Club) has their own parade. It’s like a reunion for the Westbank. You’ll see African Americans with barbecue pits sitting from one end of the route to the other. They get there early, and they stay there late. The parade’s over, they still there.

Throughout my childhood, we were on this side of the river more than we were on the Westbank. For over 40 years, my mom worked at K&B with Mr. Bucket making ice cream. She had to taste it all day at work, so she got tired of it, but she knew we all liked it, so she brought us gallons. I went to day care uptown, and when I got out, I would go in the Magnolia Projects by my cousins. All my daddy’s brothers and sisters stayed between the Melpomene and the Calliope. My grandmother stayed downtown on Elysian Fields, and we lived by her house. My best friend played sports at Hunter’s Field. At that time, I didn’t know where I was, but I knew I was somewhere I enjoyed.

My daddy brought me in the Young Men Olympics when I was seven years old. I’m 54 now. Do the math—47 years. Note: He just had a birthday so wanted to add the extra year—but he was 53 the day of the first round of the interview. You stop counting at a point. There are five of us who came in that year who are still in here. When I first started parading, I never knew that we had different divisions. My daddy put me in my group and said, “You better not move.” He was up with the older guys, and we had a young division that was for 19 and below. The teenagers like Joseph Spots were the leaders. Older guys like Uncle Ghost would leave their division and come check on us, too.

We often get that question, “Why you go back and second line, man? You should have passed that. You should have outgrown that.” For me, it’s the brotherhood that I get from the organization. I tell them a second line is not important to me. I enjoy it—don’t get it wrong—but what I want to keep is the fellowship that I have in this organization.

When I came in, we had four doctors in the club, and you had to get a physical done for free to become a member. When someone died, they would go to Gertrude Geddes Funeral Home. It was a perfect fit because the owner was a member of our organization. We had our meetings upstairs. I remember as a little boy coming down the stairs of the Elk’s Hall, and there would be three limos waiting that they donated to us. They still give us those limos every time we parade.

I graduated from high school in 1986. My senior year, I got a full scholarship to Brigham Young in Provo, Utah to play football. My daddy told me I couldn’t parade. I cried, but he told me I had to get my mind right because I was going to be the first one in the family to go away. I didn’t like it at all, but it worked out for the best. When I was playing college football, I was asked in interviews, “Why would an African American from the South come to Utah to be around the Mormons?” I said, “I came here to get an education. I came from parents, and an organization, that prepared me to survive and still be here.” I have a bachelor’s degree in social work and a master’s in management. Right now, I am in the seminary. I’m excited about that.

My father and these men right here wouldn’t call it social work, but they did so much benevolence for each other. I done seen where my dad jumped up because a member needed something. I saw what happened when my uncle Henrich was killed in the Fischer Project. He was there for work, helping a family, and they decided to rob him and kill him. Thirty men who didn’t know him showed up for my dad. From them, I learned the importance of being there.

Building Infrastructure to Support Parades

My father was chairman of the board of the Young Men Olympics for 25 years. Outside of the organization, one of his most important relationships was with Quint Davis, the co-founder of the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival. We had a picture that we got from Quint. It’s him in a parade Uptown when he’s about 11 years old, and he’s the only white person through the whole crowd. He loved the parades. My dad met Quint at one, and they talked about bringing second lines to the Jazz Fest. He told me a story that meant so much to him, and he always talked about it. Quint invited him to his house, and he said, “Oh, man, I was preparing to go to this millionaire’s house. I get in there and he don’t have a lick of furniture. We sit on the floor, we talk, drink a couple beers—for hours. And we’ve been friends ever since.”

Their friendship combined Quint’s dream of getting funding to help the organizations and my dad’s passion for being able to keep the culture going and share it around the world. I’ve traveled the world with my father, brothers, and other club members. I’ve been to Spain, England, France, and Australia. Quint was a speaker at my dad’s funeral, and afterwards they came up with the Norman Dixon Sr. Foundation, which helps fund the parading permits to make sure the organizations can be on the street.

In the city, there has always been infrastructure in place to support organizations who care about the music and provide places to meet. In the early 1900s, many of the early jazz bands held dances in buildings that were owned by the Masons and Eastern Stars. My dad brought me into the Masons, and half of our members are in the Masonic order. A lot of the operations are really close to the Young Men Olympics. We have the same kind of bylaws, and both are about brotherhood, being a part of the cycles of life: people being sick and dying, people being born, and celebrations. Sometimes I get confused of where I am but it’s so close.

In the late 80s, somebody went in Gertrude Geddes and killed the owner while we were upstairs in a meeting. We didn’t know what was going on. We suspect they were trying to rob us for our membership dues. The funeral home didn’t want us to stop having our meetings there, but we told them, “No, we don’t want this to ever happen again. Something aimed for us. We don’t want y’all to get caught up in it.”

We began meeting at different bars, and afterwards the members would just hang out. To the older members, the fellowship was more important than where they were meeting. But in the early 2000s, we told my dad, Mr. Bucket, and all those older guys, “Well, we want a building.” It wasn’t important to them, but it was important to us, so they allowed us to do it. Within a couple of years, we bought this place in 2004. As far as I know we’re the only organization that has our own building. It’s always good to have a home. When you have your own you can do what you want. We meet here, we have repasses here, we start and end our parades here.

Our grand marshal for the whole parade is Jerome “DJ Jubilee” Temple. He fits like a glove with the organization. He’s in it for what it does to help the community, and we love the commitment he has for the community. He helps so many kids through NORD’s program at Shakespeare Park, it’s ridiculous. He’s also in the Masons with me. We done had grand marshals that like to dance the whole parade and the whole parade be all out of order. DJ Jubilee is not interested in the dancing part. I guess he’s in the spotlight enough. He walks up and down the parade all four hours: “You need to walk up. You need to move. Y’all need to stop! Slow down! Speed up!”

The Body & Its Divisions

Two weeks before our big parade, we have a mini parade on our real anniversary to celebrate our organization’s existence. At that time, we go to a church of one of our members and remember the dead and celebrate the living, who are represented by the new officers who are sworn in by the minister.

For our big parade, we have six divisions and six bands. The Body is the root that can never go away. The organization pays for its band. Now, if you want to make it uniform, sometimes we’ll get together and suggest we all wear something, and that’ll look nice. But you don’t have to do that. As a member of this organization, you can just get up there with the band and enjoy yourself as long as you have black and white. Anyway you hook it up—all white, black and white, all black—that represents the organization.

If the other divisions disappear, the Body will always be there. For the last five years of my dad’s life, he wore the same black pants, white shirt with black lines in it, and his hat. He used the same fan. He’s like, “Man, I ain’t spending no more money on this.”

Charlie Brown paraded with the Young Men for years in the Body. He was a really nice guy, around my dad’s age. He was kind of a loner, but everyone knew him. He started carrying our banner, and because he knew how it’s supposed to be done— when to stop, the distance between the group and yourself—he began carrying the banners for every organization uptown and downtown. Our banner has two sides—the blue side and the black side.

The blue side shows that nobody has died between one second line year and the next. The black is if somebody has died from September to the end of August. Some organizations don’t have black, they just have dark sides and light sides, and others don’t have different sides. In parades, we always put our banner up front because that’s the first thing you want people to see—the banner with your name to know who’s coming. The only time we put our banner behind us is during a funeral. We put it behind the casket coming out of the church to the hearse.

A lot of groups have grown out of our organization. The Original Four used to be our fourth division. The Perfect Gentlemen was also from the Young Men Olympics. The Uptown Swingers was the division I was a part of before I went to college, but they broke away as well. Waldorf “Gip” Gipson wanted to stay so he changed the name to the Furious Five. When I came back from college in 1991, I told my dad, “I want to parade with the Furious Five.” He was like, “Oh, they parade with the Prince of Wales, so you know that ain’t happening.”

My daddy didn’t asked me, he just told me, straight up, “You ain’t going parade with the Furious Five no more. Them days over. You gonna get in one of these groups.” He put me in Devastation. The only guy I knew in that division was Charles “Papi” Harris, who was the president. He came in the same year as me, so I said, “Okay, I’ll go with him.” I had to hurry up and get all my stuff together in time for the parade. After two years, the Furious Five came back in 1993.

This is my first year with the First Division. We don’t have another name beyond that. When I had the Untouchables, and we wore expensive outfits. I was like, “You know man, I’m getting tired of this.” My body’s starting to hurt, and I keep myself in shape. My hands were cramped, my shoulder was like I had just been playing football. Seriously, four hours is hard. They beat you up, so I joined the First Division and 14 of the Untouchables came with me.

I put in two years in with Devastation, and then they left to parade under the Perfect Gentlemen’s banner, so there was a gap in our parade. I thought, “I can start my own group,” which is the Untouchables. While it’s good to have pride in your creativity, I told members at a meeting, “We talk divisions too much. We’re the Young Men Olympics, and that’s a wrap. I don’t want to hear about the Five doing this, the Untouchables, the Big Steppers. When you up in here, from now on, I wanna hear ‘Young Men Olympics’ and that’s it.”

We just had a little band called Sons of Jazz. Tuba Fats’ grandson, Michael, is over that band with guys who graduated from St. Augustine, and they play some good music. They can play “Lil Liza Jane” like it is 1970 and come back and hit a Maze song that they changed over to a second line song. It was the first time in 10 years that I didn’t get tired. Last year, I felt so free.

Interview conducted by Rachel Breunlin and Bruce "Sunpie" Barnes of the Neighborhood Story Project.