Michael “T. Mayheart” Dardar Sr. grew up part of the Houma tribal community in Venice, where a sign at the road’s end marks the “Southernmost Point in Eastern Louisiana.” Beyond it lie several miles of marshland and then, the open Gulf of Mexico. Dardar, a marine diesel mechanic, historian, and writer, is a member of the United Houma Nation and served on the tribal council for 16 years, many of them as vice-principal chief. His father worked on the water, living the seasonal life of fishing and shrimping that is traditional to the Houma and Louisiana’s other indigenous coastal communities. He was living in twin city Boothville in 2005 when Hurricane Katrina struck, destroying his home. The displacement sent him further inland in Plaquemines Parish, and he has since landed in Raceland, in Lafourche Parish.

A 1974 image shows a net rack at a fishing camp in Fala, Louisiana. Fala was the site of an important Native American settlement, but by the end of the 1980s it had been completely overtaken by Gulf waters. (THNOC, © Douglas Baz and Charles H. Traub, 2019.0362.13)

Dardar’s house fared “better than others” in Hurricane Ida, which hit the southeastern coast of Louisiana as a Category 4 hurricane on August 29—one of the most powerful storms ever to impact the United States. He’s got roofers lined up to repair his house, but the damage to his Houma community at large is still extensive and far-reaching in its implications. “Right now, a large portion of the communities, especially lower-bayou [coastal] communities, they’re still in shock,” he said. “Aid hasn’t really gotten to them. So many people still are looking for a place to stay. Just day-to-day existence is occupying them now. It’s rough.” Dardar checked in recently with a tribal elder down the bayou who said approximately one in five people he’d talked to can’t see coming back to rebuild.

The full extent of Ida’s impact on coastal demographics remains to be seen, but for Louisiana’s indigenous people, it’s another wave in a long saga of forced migration and environmental adaptation going back hundreds of years. Pushed ever closer to the Gulf in waves spurred by European colonialism, US expansion, and the associated manipulation of the region by a progression of various industries—logging, furs, and oil and natural gas—Louisiana’s Native Americans now face a dire dilemma, as the long-forecast effects of climate change and coastal erosion overtake the land they love.

“We are the forgotten people,” said Theresa Dardar of the Terrebonne Parish–based Pointe-au-Chien Indian Tribe, speaking to Julie Dermansky for the website DeSmog. “My poor people. They have nothing left. They’re salvaging a few things.

“We’ve all been warned that indigenous people are going to get hit worse with climate [change], and this is what happens.”

*

By the time René-Robert Cavalier, sieur de La Salle made France’s first exploration of the Lower Mississippi River valley in 1682, the Houma nation had established itself in a fertile area of rich floodplain and steep hills north of modern-day Baton Rouge. Tribal bands traveled among seasonal villages and enjoyed the strategic and agricultural advantages of their lands. “We had principal villages, hunting villages, we had fishing villages,” T. Mayheart Dardar said. “Our experience with the land was much broader than it’s usually depicted.”

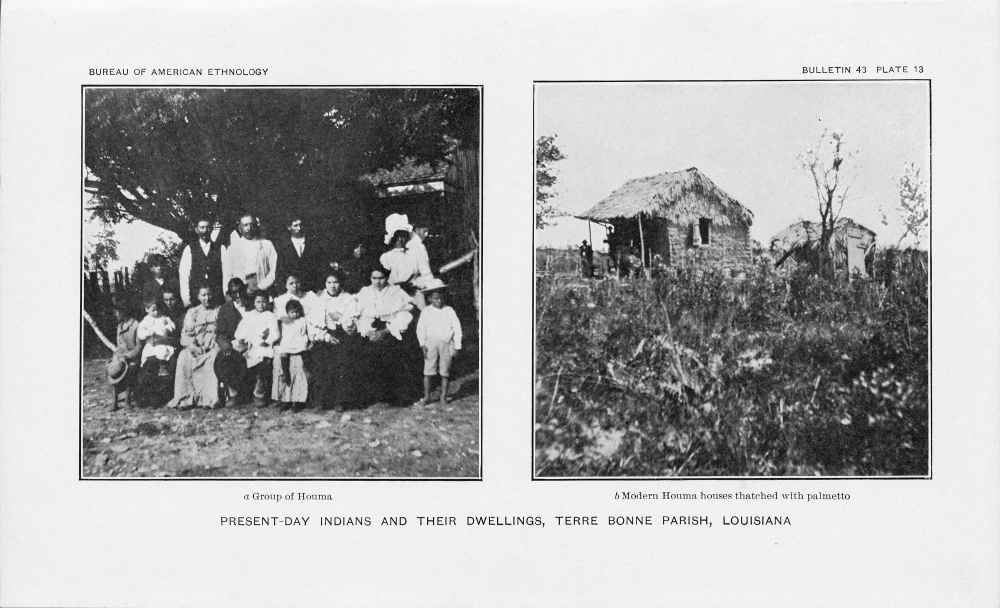

Published by the Smithsonian Institution in 1911, John R. Swanton’s Indian Tribes of the Lower Mississippi Valley and Adjacent Coast of the Gulf of Mexico was the first comprehensive ethnological study of indigenous peoples of the Gulf South region. This spread from the book shows Houma people in Louisiana’s Terrebonne Parish in the early 1900s. (THNOC, 89-181-RL)

That homeland changed over the first half of the 18th century, as the Houma and other Native American tribes across southeastern North America were drawn into France and England’s fight for dominance of the region. The Houma had established a strong alliance with the French in 1699, with the arrival of Pierre Le Moyne, sieur d’Iberville, which made them targets of attacks by the English-allied Chickasaw. The decades of roiling conflict between the colonial powers and their Native proxies, culminating in the French and Indian War (1754–1763), eventually pushed the Houma southward, toward the modern-day parishes of Terrebonne, Lafourche, and St. James.

After Louisiana became a US territory in 1803, the Houma sought recognition from the federal government for 8,000 acres of traditional tribal land, but that request was denied.

“The Houma survived by grouping their land under the individual land titles of their leaders and rebuilding their settlements in the inaccessible swamplands south of the town of Houma, Louisiana,” Dardar writes in his 2014 history Istrouma: A Houma Manifesto / manifeste Houma. There, they hoped, they’d be left alone to continue as a nation, living off the land using their traditional skills of fishing, trapping, planting, weaving, and more. It’s no coincidence that the town of Houma was founded by white settlers—and named after the tribe—only after the Houma people began to migrate south. “From the 1830s till the dawn of the 20th century, the Houma prospered as subsistence farmers, hunters, and trappers in the wilderness regions of Bayou Lafourche and Bayou Terrebonne,” Dardar writes.

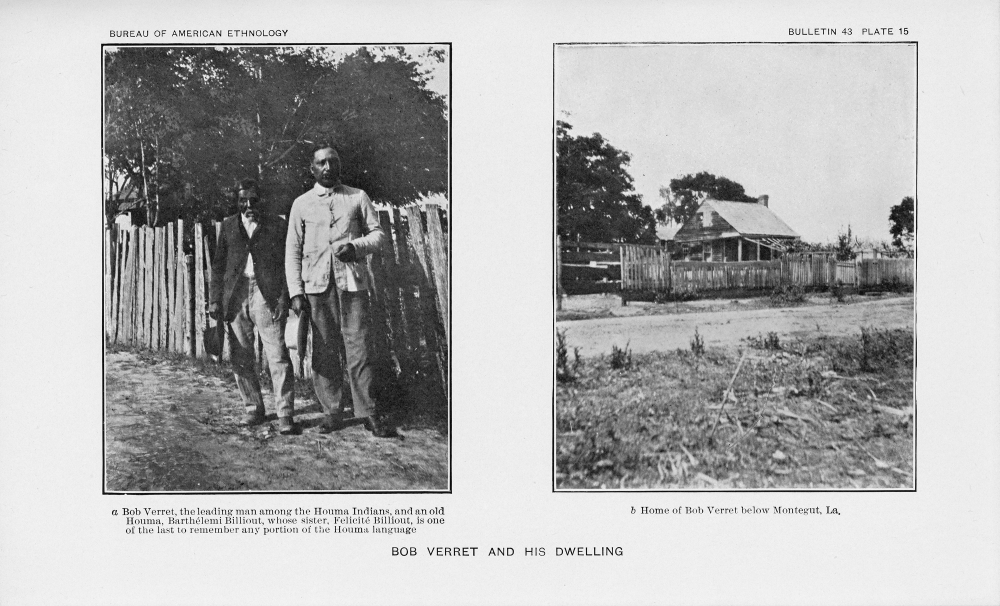

The left image in this spread from John R. Swanton’s Indian Tribes of the Lower Mississippi Valley shows a Houma elder, Barthélemi Billiout, and Bob Verret, a tribal leader, during the first decade of the 20th century. Swanton’s caption says that Billiout’s sister was reportedly the last Houma to remember the tribe’s mother tongue. During the second half of the 18th century, Houma began adopting French as their primary language, and the process was complete by the end of the 19th century, though portions of the original language remain known today. (THNOC, 89-181-RL)

That period of stability changed with the rise of the fur industry at the turn of the 20th century, followed closely by that of the oil and gas industry.

“Politically connected businessmen were buying up Louisiana swampland for a per-acre price better than the Louisiana Purchase a century before,” Dardar writes. Many of the indigenous people who lived there held legitimate titles to discrete parcels, and collectively the tribe shared the expanses of marshland that had previously been ignored by the rest of the world, but that distinction mattered little to the ruling class. Through the political, policing, and business arms of white supremacy, many Houma families were stripped of their property and rights. “With the local politicians and law enforcement in their pocket, the landowners were soon able to force the Houma to pay for trapping leases on lands that rightfully belonged to the tribe,” Dardar writes. Often, indigenous families were invited to sign documents purportedly for a lease agreement, only to be told later they had signed away their land entirely.

As energy infrastructure developed over the 20th century, damming, dredging, and diversion triggered the acceleration of coastal erosion. Saltwater from the Gulf entered fresh and brackish waters, gradually killing off trees and wildlife that had once been plentiful around the coastal indigenous communities.

The energy infrastructure of the 20th century accelerated coastal erosion in southeast Louisana. This image from the 1970s shows an oil rig in Terrebonne Parish. (THNOC, © Douglas Baz and Charles H. Traub, 2019.0362.93)

In her 2019 book with the Neighborhood Story Project, Return to Yakni Chitto: Houma Migrations, the artist Monique Verdin reflects on the environmental degradation of the Louisiana coast and its effects on her Houma family down the bayou. (Verdin is also a community advisor to the board of The Historic New Orleans Collection.)

“In South Louisiana, we live on a power point of our planet. A place where water comes to be purified. A place where 1,000-year-old cypress trees once grew. . . . A place close to the Gulf of Mexico, but where, as the old people used to say, ‘sweet water’ could still be found that was fresh and good to drink. There is no sweet water down the bayou in Terrebonne Parish anymore.”

For many indigenous residents of southeastern Louisiana, Hurricane Katrina, in 2005, was an early sign that the delicate balance of environmental adaptation begun centuries ago was on the verge of collapse. Because of the massive loss of wetlands over the second half of the 20th century, the storm devastated coastal communities in a way that has had lasting effects.

“My family survived [Hurricane] Betsy [in 1965], but the community rebuilt itself,” Dardar said. “The community was vibrant. Coastal erosion wasn’t really there yet. But it was a completely different experience after Katrina. We’re one of the families that didn’t go back.”

A further blow to the region came in 2010 with the British Petroleum Deepwater Horizon oil spill, which sent an estimated 206 million gallons of crude into the Gulf—approximately half of which remains there today, according to a recent congressional report. Marine populations plummeted, hampering the livelihoods of thousands of coastal workers for years. In 2010 alone, the spill cost the seafood industry close to $1 billion, the Times-Picayune reported.

*

Today, the indigenous presence in southeastern Louisiana comprises one large and several smaller tribal entities: the United Houma Nation (population ~19,000), the Pointe-au-Chien Indian Tribe (~800), and three groups—based in Isle de Jean Charles, Dulac/Grand Caillou, and lower Lafourche—known as the Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Confederation of Muskogees (~1,000). The tribes were all part of the United Houma Nation until the mid-1990s, when Pointe-au-Chien and the confederation split off, largely in response to the Houma’s unsuccessful effort to receive federal recognition.

A teacher and a group of students sit for a photograph at a school for indigenous children in 1930s Houma. The Houma people’s fight for equal access to education consumed the first half of the 20th century in the political life of the tribe. (Courtesy of the State Library of Louisiana)

That process has its roots in that moment after the Louisiana Purchase when the US denied the tribe collective rights to their 8,000 acres. The recent effort began in the late 1970s with the formation of the United Houma Nation, which filed its petition for reocognition to the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) in 1985. What was supposed to be a one- to two-year process dragged on until 1994, when the BIA rejected the Houma’s petition, citing a lack of “direct bloodlines to indigenous heritage,” Verdin writes.

Creolization, or the coexistence and intermingling of many ethnic groups with sets of shared or overlapping cultural traits, was a driving force in Louisiana’s colonial and postcolonial history, and Native Americans were part of it. “The ethnic identities of the Houma are complicated,” Verdin continues. “Some lines of our family genealogy can be traced back to France. In other colonial documents, our relatives have been listed as ‘griffe.’ During the Spanish era, this designation was for mixed people of African and Indian ancestry.”

Not only did the failure of the federal recognition process and the ensuing tribal schism leave “a scar in families that many are still healing from,” as Verdin puts it, but it also has left the tribes without federal protections and resources that could assist them as they face the increasing threats to their survival. “We’d have access to HUD programs and [BIA] Indian programs,” Dardar said. “That lack of federal recognition, it severely limits our options.”

Even the most high-profile effort by federal and state bodies to assist indigenous communities has had a bumpy journey. In 2016 the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) awarded Louisiana $48 million to relocate residents of Isle de Jean Charles, an indigenous community along the coast of Terrebonne Parish. Ninety percent of the area’s terra firma has been lost to coastal erosion since the 1950s, leaving just a narrow strip of land flanked by houses that cannot withstand the kind of powerful storms that are becoming more than a once-in-a-century event.

Dubbed the “first American climate refugees” by the New York Times, the Isle de Jean Charles residents looked forward to collaborating as a tribe with state officials on the relocation project, but that hope soured. In 2019 Albert Naquin, chief of the Isle de Jean Charles tribe, formally withdrew his support for the project, accusing state officials of shutting tribal leaders out of the project’s planning and administration.

Still, the resettlement effort is underway: state contractors broke ground over the summer on what’s being called New Isle, located on 515 acres north of Houma. Almost 90 percent of the island’s 42 households plan to relocate, according to the Houma Courier’s Kezia Setyawan. However, the long road to completion has left some island residents without housing post-Ida, lamented Chief Naquin in an interview with THNOC. “It’s been five and a half years!” he said. “A developer can build a subdivision in one, two years. We’ve got people in tents, where they could have already been rehoused.”

A blanket of oyster shells bridges the water from land in this 1920s image of the house of an indigenous family down Bayou Grand Caillou. (Courtesy of the State Library of Louisiana)

Isle de Jean Charles is just one small village. What is to come for other communities at the bottom of “the boot”? Another migration may be taking place. For those who stay, Dardar believes they’ll find their community fabric weaker with every storm.

“It’s going to continue to happen,” he said of the cycle of destruction, displacement, and the struggle to rebuild. “I saw it in my experience in Katrina. And it’s not just the indigenous communities, it’s all these poor coastal communities: as more of these storms come in, you lose businesses, you lose schools, you lose resources.

“These excessive storms become community killers. Those that are able to get out get out. Some of them move up the bayou and some of them move to a completely different area. There’s nothing anymore to reverse that tendency.”

Relief efforts are ongoing and still urgent in these communities. Many people are still without housing or substantial aid for relocating or rebuilding. Donations to the tribes mentioned in this piece can be made at their websites:

Grand Caillou / Dulac Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Confederation of Muskogees

Isle de Jean Charles Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Confederation of Muskogees

Dry Cypress

by T. Mayheart Dardar

reprinted with the author’s permission

I close my eyes and look behind

And see the days gone past

Seagulls sing, the nets are full

How I wish those times had lasted

There was always freedom on the water

A chance to live my grandfather’s life

To carry on the Houma traditions

To be untangled from modern strife

But now when I open my eyes

Dry cypress is all I see

Reminders of a homeland washing away

Reminders of a world that used to be

Children of the bayous we are

Generations uncounted amid their glory

Like brothers bound by blood

The land and the people share the same story

The land and the water were eternal

They both protect and provide

Like a loving parent they were there

And in their bosom we abide

But now when I open my eyes

Dry cypress is all I see

Reminders of a homeland washing away

Reminders of a world that used to be

In the days of our fathers there was balance

Fresh and salt, land and water

But Atayk-nahollo came with no respect

He came from greed and slaughter

If I stood today at my childhood home

More than my feet would be wet

How much more will disappear beneath the tide

Today before the sun will set