John Ed Bradley grew up in Opelousas, Louisiana. The only images on the walls of the small bedroom he shared with two younger brothers were posters of football players. “That was my first art collection,” he said.

At Louisiana State University, where he was starting center on the football team, an art history class changed his life. “I was trying to boost my GPA,” he said. “Somebody told me that art appreciation was an easy A. This would have been 1976 or ’77. I was the rare student who really appreciated the art. I loved the art. I started going to these student shows in the student union at LSU. Whenever a new show would go up, I would go and have a look. I just got the bug. I loved it.”

His profession was to be writing, as uncharacteristic as art appreciation for an offensive lineman. Bradley’s career took him to the staff of the Washington Post and for several years amid the many art museums in Washington, DC. He later wrote for Sports Illustrated, Esquire, and other outlets that paid him to travel to other places with great art to enjoy. And, eventually, possess.

“I started buying art,” said Bradley, now an established author whose career bibliography includes celebrated novels and the sublime memoir of his life at and after LSU, It Never Rains in Tiger Stadium: Football and the Game of Life. “I determined at some point that I was going to be a collector.”

An early interest in the art of the Works Progress Administration era (“I used to see it on campus at LSU”) evolved into a specific appreciation for New Orleans and Louisiana artists. In addition to acquiring the art, Bradley also set about acquiring the artists’ biographies, bits of reporting he stored in Manila folders. “I was this weird collector,” he said. “It wasn’t enough to have just the art. I wanted to have the stories.

“And I started to interview people. Everywhere I went, people talked about John Clemmer.”

Fridays with John

Bradley was familiar with Clemmer’s work but not yet an investor in his art. “I wasn’t collecting abstraction,” Bradley said. “It wasn’t until I met him and got to hang out with him that I fell in love with modernism and fell in love with his work.”

As recounted in an essay in the catalog that accompanies the THNOC exhibition John Clemmer: A Legacy in Art, Bradley first sought out Clemmer in 2002 to help him fill his Manila folders with stories about Paul Ninas, Weeks Hall, Alberta Kinsey, and other artists with works on view in the “Clemmer’s Circle: His Teachers, Students, and Colleagues” portion of the show.

Clemmer (left) and Bradley are pictured at the artist's home in Sheboygan, Wisconsin in this 2003 photograph.

The essay begins: “In the beginning, we met on Fridays for lunch. It was always shrimp po-boys and Barq’s root beer from Barcia’s Grocery, served in the large, light-filled room where he painted.”

Clemmer was uniquely positioned as a source for satisfying Bradley’s curiosity. A student, teacher, and director of the influential Arts and Crafts Club of New Orleans, Clemmer later taught at Tulane University’s School of Architecture and chaired the Newcomb College Art Department. To Bradley, it seemed he knew, or knew things about, everybody.

To prepare to meet Clemmer, Bradley had methodically educated himself about the artist, who at mid-century had been a titan of New Orleans modernism. “I spent time in the Williams Research Center reading the files,” Bradley said. “I remember reading that John had been this huge star as a young guy. He was a big deal, a prize winner.

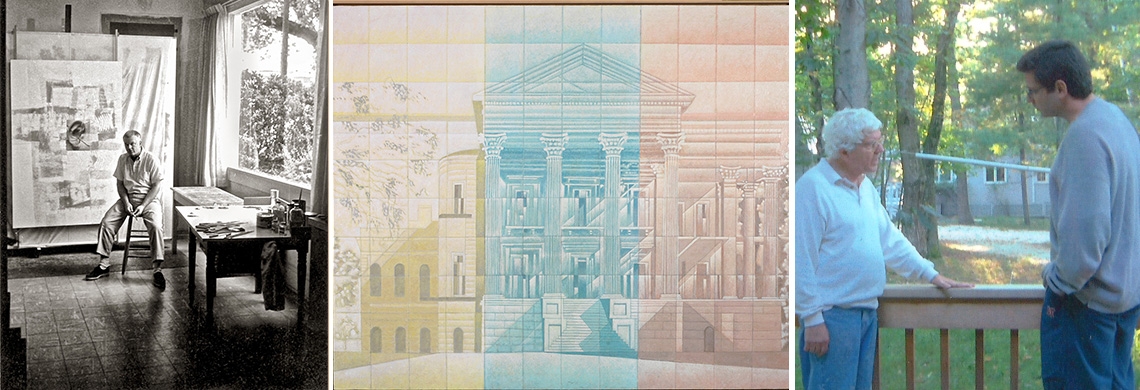

John Clemmer is pictured in his Foucher Street studio in New Orleans, around 1965. (Photo by Milton Scheuermann Jr., courtesy of the John Clemmer archive)

“He was kind of a force.”

And, at the time of their first meeting, John Clemmer was 80 years old (almost twice Bradley’s age) and “somewhat obscure at that point,” Bradley said. “He had kind of fallen off the radar. He’d just had a show at NOMA,” a major retrospective at the New Orleans Museum of Art, in 1999. “After that, things weren’t really happening.”

Always an adventure

"There was something about him that was very familiar to me,” Bradley said. “I realized we had similar backgrounds. He had a father from the Midwest who'd married a Louisiana girl. My grandfather was a guy from the Midwest who'd married a Louisiana girl. So we came from the same places and the same kind of people. We just understood each other, and we spoke the same language.”

Both collected—or in Clemmer's case, accumulated—art by Louisiana artists.

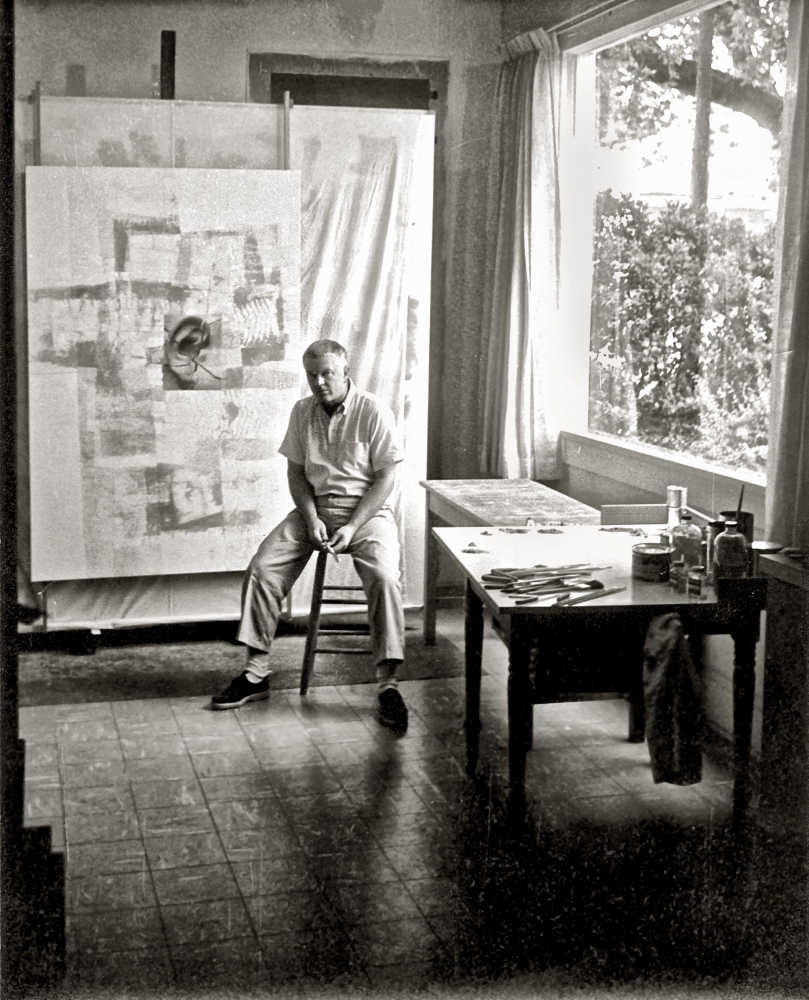

Clemmer's career as an artist spanned more than 70 years, and his works featured influences from varying styles, including regionalism, cubism, and geometric abstratction. (left: Belle Grove II; THNOC, gift of Susan Brill and Michael S. Hirshfield, 2016.0400.1; right: Topographia VIII–Azteca; courtesy of 3618 Studio LLC, New Orleans, LA)

“I was always digging” on visits to Clemmer’s studio, Bradley said. “He had these flat files, all these drawings. He had racks filled with canvases. He had old paintings on canvas rolled up and stored up high. You’d have to get on a ladder to dig around in there. I’d find things by his friends. Robert Helmer, Shearly Grode, other artists who had given him things. It was always an adventure.”

As was the conversation, which ranged from artists they knew—personally in Clemmer’s case, mostly through paintings in Bradley’s—to paint, solvents, canvas, and sometimes more personal matters.

“We talked about all of these artists,” Bradley said. “We talked about all these people. He knew a lot of their secrets.

“He trusted me, and he was somewhat confessional with me, which I really appreciated. There was no question he wouldn’t answer. He never said, ‘Turn off the recorder’ or ‘This is off the record.’ If he said it, I could take it to the bank.

“He was a gentleman. He was easy to talk to. He always sort of looked grumpy in pictures, but he was the sweetest guy.”

Reflections

After a recent visit to the exhibition, Bradley reflected on some of what he’d seen and the artists he’d researched.

Portrait of Alberta Kinsey by James Lamantia

Portrait of Alberta Kinsey; 1942 or 1943; oil on paper; by James Lamantia (1923–2011), painter; THNOC, 1993.108.7

Bradley estimates he once owned more than 30 works by Kinsey (1875–1952). In his essay for A Legacy in Art, he recalls visiting her grave in Ohio and meeting her cousin, Jack Kinsey, who had several of her paintings. “I made an offer for everything, just threw out a sum,” Bradley said. “He looked at me like I was nuts. His wife’s name was Frankie. We were in the basement. He looked over toward the stairs and said, ‘Frankie, go get some cardboard boxes!’”

Dauphine Street by Charles Henry Reinike

Dauphine Street; 1943; watercolor on paper; by Charles Henry Reinike (1906–1983), painter; THNOC, gift of Mrs. P. Roussell Norman, 1980.47.13

“Reinike is primarily remembered today as a watercolorist,” Bradley said. “He also worked in oils. He painted the local scene. He probably could be described as a regionalist, and his region was Louisiana. This is one of his best watercolors that I have seen. He often painted the Louisiana landscape and included in those scenes little shacks, little country shacks with a Black figure on the porch or out in the yard. He painted a lot of those. I think those helped pay the bills.

“He poured himself into this piece. It appeals to me. It has a definite narrative. These guys just had a beer on Bourbon and heard about this spot and they’re a little timid. Those old cypress shutters are closed. Inside, candles are burning, maybe a little incense.

“John [Clemmer] thought highly of Reinike.”

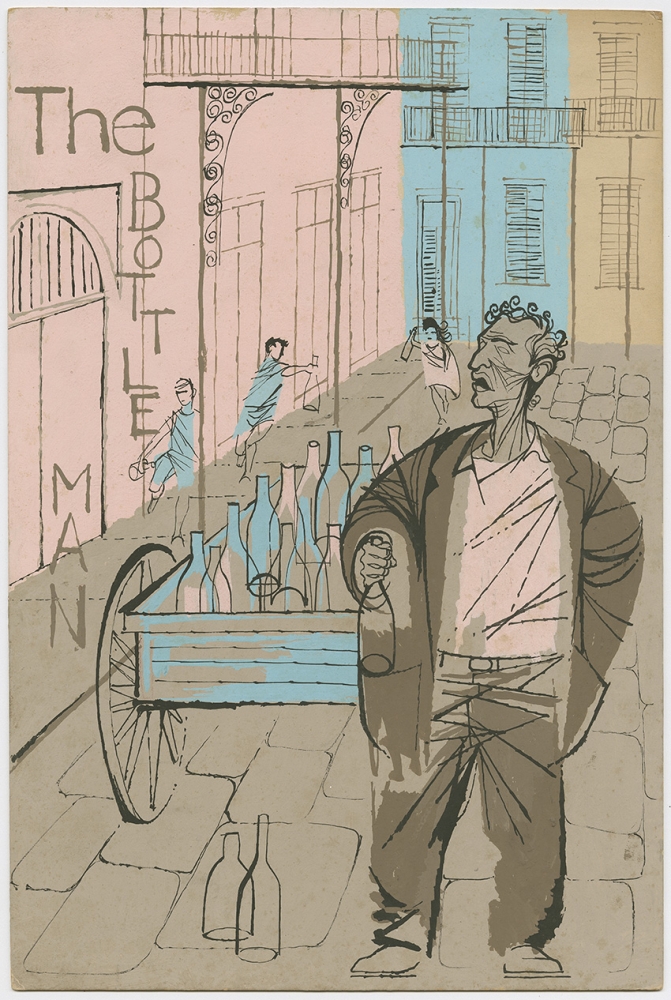

The Bottle Man by Robert Helmer

The Bottle Man; between 1954 and 1964; gouache on illustration board; by Robert Helmer (1922–1990), painter; THNOC, gift of John F. Clemmer, 1991.116.19

“The Bottle Man was one of those iconic French Quarter figures,” Bradley said. “When I look at the early 20th century art of the French Quarter, different characters appear again and again, by different artists. A lot of times you see an antiques peddler, a guy with a little cart with pots and pans or a lamp, things he picked up off the street. The guy who sells fruit, the taffy guy . . .

“All those different people, you see them again and again. They were colorful characters. I guess a lot of the artists came from elsewhere, came from the Midwest, and it must’ve been very exotic for them in New Orleans, in this old district, and see these people. It strikes me that they sell for thousands of dollars and that the person in the picture might’ve had five cents in his pocket.

“When I first saw one of these, it was John’s. Helmer was a modernist like John. It took some courage to be a modernist. People had not seen that kind of art before. People did not appreciate it.

“Most artists would write the title on the bottom. He wrote the doggone ‘Bottle Man’ right across the image.”

Conglomerate #2 by Shearly Grode

Conglomerate #2; 1978; mixed media with gold leaf and silver leaf; by Shearly Grode (1925–2003), painter; THNOC, gift of John Clemmer, 2009.0171

“That painting was displayed in John’s living room,” Bradley said. “He really admired her work. It’s probably not for everyone. I’ve seen her work at auction and it doesn’t bring big money. He responded to it. He thought it was unique, important. He had a lot of art and much of it was squirreled away in his studio. For him to display this in his home tells you something.”

Emma by Colette Pope Heldner

Emma; 1924; plaster with paint, by Colette Pope Heldner (1902–1990), sculptor; courtesy of Don Fuson

“Who do you think she was?” said Bradley, who once owned the sculpture. “This would’ve been 1923 or ’24, so Colette would’ve been 22 years old . . . and would’ve been new to the city.

“We do see portraits of Black people from that period. It might’ve been because they were inexpensive sitters or maybe they . . . would’ve appealed to collectors.

“Who do you think that young woman is? Do you think she was a friend? Did she work as a laborer for the Heldners? Did she work in the neighborhood? Did Colette like the look of her face? I wonder, who was this girl? Who was Emma?”

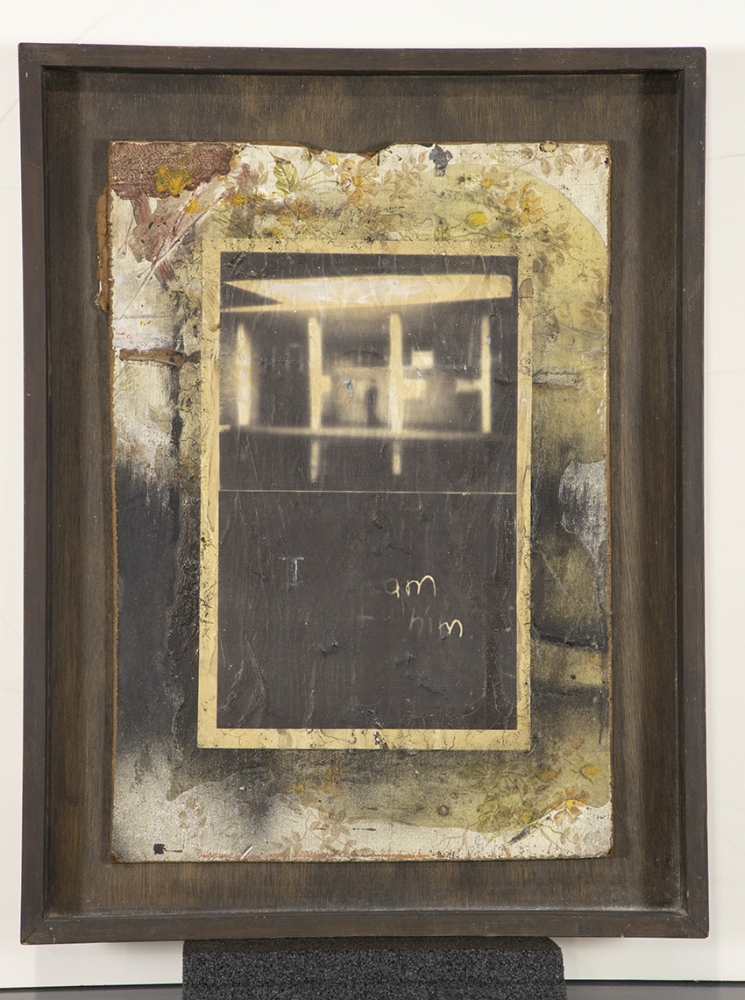

Goodbye Dad by Jan Gilbert

Goodbye Dad; 1989; mixed media with photographic print; by Jan Gilbert (b. 1953), artist; THNOC, acquisition made possible by an anonymous donor, 2019.0447.1

Jan Gilbert’s Goodbye Dad is the last piece in the “Clemmer’s Circle” gallery. It’s one of a series of related works in tribute to her father, once a major league baseball player.

“John talked about her,” Bradley said. “When I saw that piece, it just struck me. It’s deep. It’s very powerful. I was blown away, but first I had goosebumps.

“I responded to it because it’s about her dad, who had been an athlete. I just thought it was beautiful and haunting. It hung around and hung around. It stayed with me.

“I think, too, when I looked at her series, I thought of my father. It made me think about my dad and who he was to me and what I might’ve been to him.

“I love where it was positioned in the show. You see all this work, then there it is. It’s speaking to you from the wall as you’re trying to walk past.”

Editor's note: The companion catalog for the exhibition John Clemmer: A Legacy in Art, which features an essay by John Ed Bradley, is available for purchase from The Shop at The Collection. Click here to buy your copy.