Editor’s note: For Oscar Dunn’s full story, purchase a copy of Monumental: Oscar Dunn and His Radical Fight in Reconstruction Louisiana by Brian K. Mitchell, Barrington S. Edwards, and Nick Weldon.

Congo Square had never seen an evening quite like this one. “Hissing winds . . . blew fitfully from the north, northeast, and northwest, laden with the icy breath from Siberian snows,” reported one New Orleans paper. Mourners, bound up in coats and scarves, packed into three stands surrounding the square, “which was brilliantly illuminated by a thousand lamps that threw a ghostly glare over the squads of moving spectators.” Lt. Gov. Oscar James Dunn had been dead almost two weeks and, despite the cold December weather in 1871, a fire still burned in the hearts of his friends and supporters who had gathered at this commemoration ceremony.

One person in particular arrived with a white-hot zeal to reveal shocking details about his friend’s final days.

Canal Street is shown here in 1871 or ’72, right around the time of Oscar Dunn’s death. Dunn’s residence was not far from this location. (THNOC, The L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1965.90.268.5)

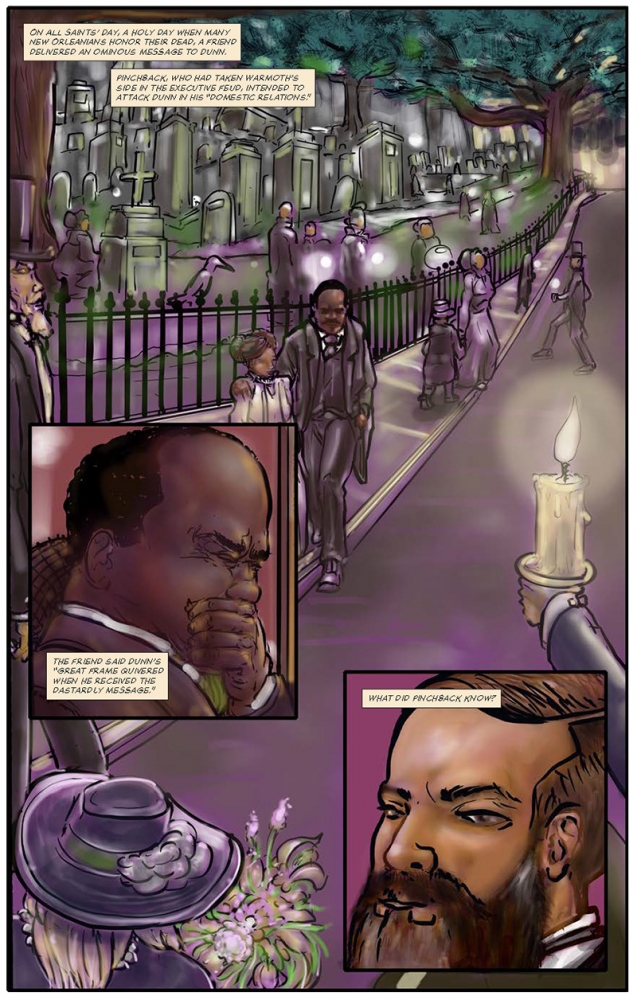

More than a month earlier, on All Saints’ Day, Oscar Dunn still walked among the living, was still the first Black lieutenant governor in America, was still mired in an intractable power struggle with Louisiana’s young, white governor, Henry Clay Warmoth. Recently, another rising Black political figure had inserted himself into the feud by forming an alliance with Warmoth: P. B. S. Pinchback.

On All Saints’ Day, with tensions boiling over, Dunn ran into one of the few men he could trust, at the corner of Canal and St. Charles. The friend, Thomas Morris Chester, had disturbing news.

Pinchback, Chester told Dunn, planned to allege corruption against the famously upstanding lieutenant governor and had already attempted to tarnish his name during a meeting with none other than the president of the United States, Ulysses S. Grant. Worse, another friend told Dunn that Pinchback “intended to attack him in his domestic relations.”

Though the specifics of the threat are unknown, it’s possible Pinchback had discovered a detail about Dunn that could have been perceived as scandalous: that Dunn had boarded at the home of his wife, Ellen, and her first husband, years before they married. In the wrong hands, that information could be used to suggest impropriety on their part prior to her first husband’s death—or even call into question the legitimacy of Ellen’s children, whom Dunn adopted as his own when they married.

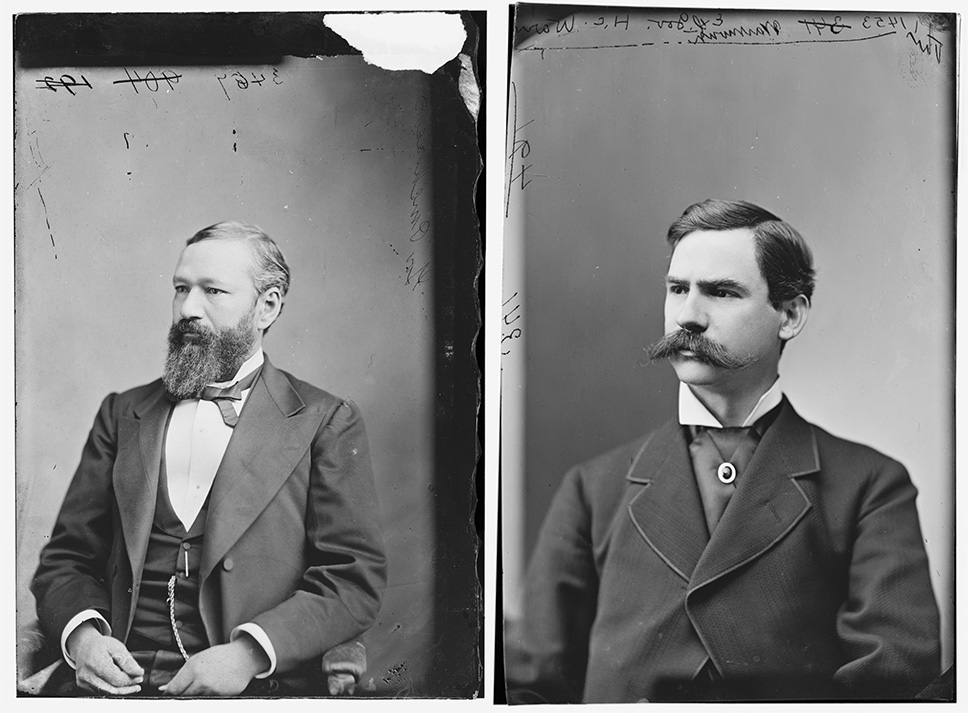

Once allied with Dunn under the Radical Republican banner, Gov. Henry Clay Warmoth (right) and P. B. S. Pinchback (left) had become rivals of Dunn’s by the time of his death. (Images courtesy of the Brady-Handy photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-cwpbh-03725 and LC-DIG-cwpbh-03857)

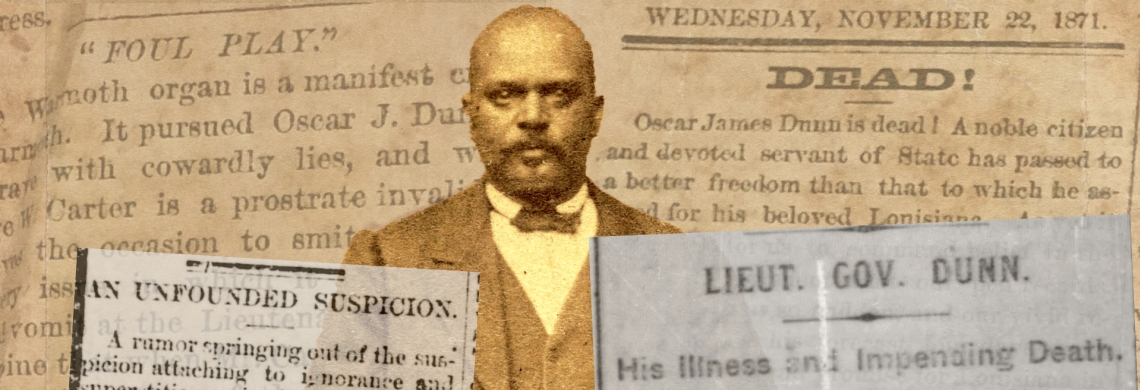

The hostility ended abruptly, however, on November 22, 1871, when Dunn died at age 49 following a brief and violent illness. From the crowds that soon gathered outside his New Orleans home, the rumor that he had been poisoned spread quickly. A family spokesperson declined an autopsy. Newspapers tried to quell the uproar by publishing a statement signed by four doctors who attended to him, stating, officially, that he had died of “congestion of the brain and lungs.”

Conspicuously absent were the signatures of three other doctors who visited Dunn, including the prominent Afro-Creole physician and publisher Dr. Louis-Charles Roudanez. This combined with the suddenness of Dunn’s illness and the degree of political rancor in the city allowed the poisoning rumor to persist. Soon, with some wrangling by Warmoth, the legislature would install Pinchback in Dunn’s place as lieutenant governor.

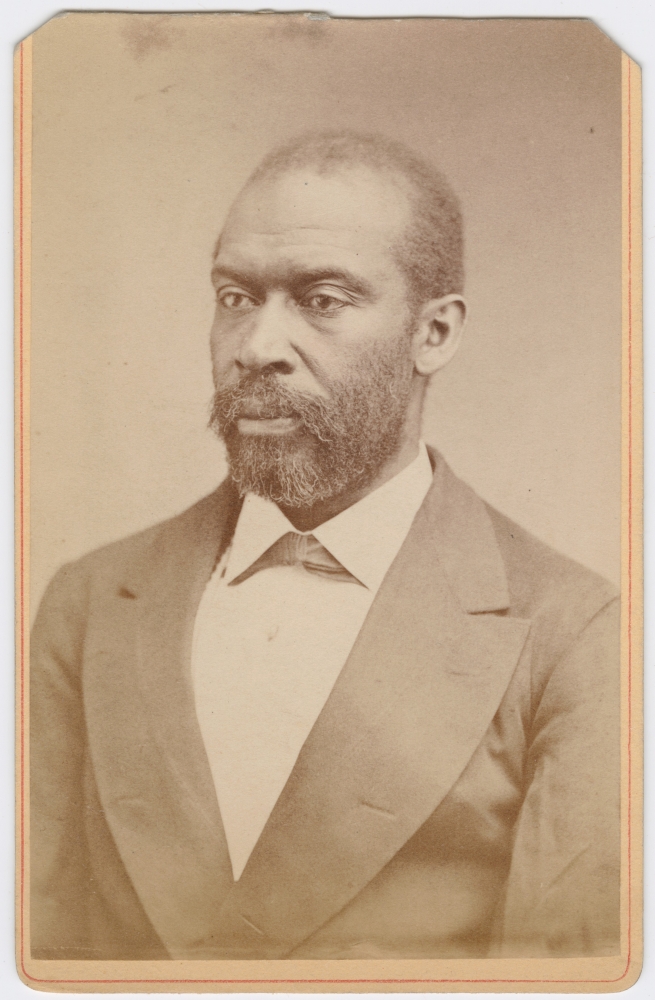

That wintry night in Congo Square, Chester, an esteemed Black lawyer and former Civil War correspondent, made public the details of his All Saints’ Day conversation with Dunn. Instead of offering somber reminiscences, Chester used his time on the grandstand, under the glow of the spectral lamps, to convey how Dunn reacted to the threats, incorporating inflammatory language that would do little to allay fears that he had been assassinated:

His great frame quivered when he received the dastardly message, and though he hurled back a defiance, it was easy to be perceived that the envenomed arrow had reached his heart, where its poison was doing the deadly work. Though infidelity of friends, partisan treason, personal rancor, official indignities and incorporate insults had made him groan in the spirit . . . when he meditated over the impending blow that was to include his estimable and accomplished consort, and the orphaned children to whom he had been a father, his great heart burst with grief: and when disease came, his mind, which had been too heavily charged with solicitude for those who were nearest and dearest to him, immediately dissolved itself into chaos, or passed to unknown realms, whither his soul soon after took its flight.

On November 1, 1871—All Saints’ Day—Oscar Dunn learned that P. B. S. Pinchback intended to allege corruption against him and “attack him in his domestic relations.” The news of Pinchback’s betrayal stunned the lieutenant governor. (Image from Monumental; illustration by Barrington S. Edwards)

Dunn’s conflict with Warmoth began not long after they were elected together in 1868, starting with the governor’s veto of a civil rights bill, which many Black leaders and constituents felt was a betrayal of campaign promises. Dunn, meanwhile, had built a reputation for being an honest, fair leader, even as corruption scandals enmeshed Warmoth and the state legislature. Dunn had also established a formidable base of supporters among Louisiana’s freedmen, who made up the great bulk of the Republican Party’s electorate.

With Warmoth’s popularity plummeting and Dunn forming key alliances with powerful federal officials stationed at the US Customhouse in New Orleans, the party finally split in the summer of 1871 and held two rival conventions. Warmoth and Pinchback held a “bolter” convention in protest of Dunn’s gathering, which had the backing of President Grant and the federal government. Afterward, Warmoth sent Pinchback and nineteen other men to Grant’s summer home in Long Branch, New Jersey, to try and win him over and air their grievances about Dunn and his allies in New Orleans.

They received a cold reception. Dunn then wrote a widely publicized letter that castigated Warmoth for abandoning his constituents and labeled him “the first Ku-Klux governor of the party he has disgraced.”

Pinchback had once been the very man who recommended that Dunn join Warmoth’s ticket, but a career of pragmatic political calculations set the stage for his turn against his fellow Black leader. The son of a white planter and a formerly enslaved woman, Pinchback spent his formative years in Ohio, before coming to New Orleans just before war broke out. He quickly landed in trouble, stabbing another free Black man in the street and being described by a court as “intemperate.” For unknown reasons, he served only a month in jail and ended up joining the Union army, where he rose through the ranks before resigning in protest of racist regulations.

He transitioned to politics, where he proved to be a talented operative inclined to giving impassioned speeches. Once, during a particularly bad stretch of violence against Black citizens, he said the following on the floor of the state senate: “The next outrage . . . will be the signal for the dawn of retribution. . . . For patience will then have ceased to be a virtue, and this city will be reduced to ashes.”

Dunn (center) made history when he was elected the first Black lieutenant governor in US history in 1868. He also briefly served as the first Black acting governor in 1871. P. B. S. Pinchback (bottom center) turned against Dunn late in his term, and succeeded him as lieutenant governor after his death. (THNOC, 1979.183)

Pinchback’s history of violent language—and actual violence—surely made many of his peers wary of crossing him. To the Congo Square crowd, Chester called out the “wandering Machiavellians who recently pilgrimaged to Long Branch,” and noted that “to my certain knowledge there was one colored man who undertook this infamous work” of slandering Dunn to the president.

Later in the speech, Chester’s indignation turned to an article critiquing Dunn published just four days after his death in Pinchback’s own newspaper, the Louisianian. Again, Chester avoided naming Pinchback, but did not hide his outrage:

Hardly had the tomb been closed over his mortal remains . . . [did] the Louisianian, under the immediate and responsible control of a well-known colored man . . . attempt to rob him of the esteem which was so universally accorded while living, and to blur his memory. Such manifestations, over the body of a worthy and lamented citizen, indicates a malignancy of heart which would not scruple at any means, if the courage were present, and interest required it, to compass death.

Dunn first fell violently ill the evening of November 19, 1871. His condition rapidly deteriorated over the next two days, as friends and political leaders anxiously filtered in and out of his home. He was declared dead early on November 22, officially of “congestion of the brain and lungs.” (Illustration by Barrington S. Edwards)

In other parts of his speech, Chester widened the net of blame, his accusations echoing across chilly Congo Square: “Ye who pursued him with such unrelenting fury, go to yonder city of the dead and look upon your ghastly work. . . . I arraign you, one and all, to answer before the bar of public opinion for the moral murder of Oscar James Dunn.”

Less than a month later, Chester (right) was walking home from a New Year’s Day party at a friend’s house. Night had fallen, and he didn’t see the drunken men in the bushes who sprang out and then dragged him onto the front lawn of a woman’s house. According to the Weekly National Republican of New Orleans, a shout from the men rang out: “Pinchback, Pinchback, Governor Pinchback, ho!” Pinchback stepped forward, and one of the men asked him, “What shall we do with him?”

Pinchback offered protection to Chester, who spat back that he would rather die than owe any protection to a man like him. The men immediately began beating Chester with sticks and knives. At some point, Chester made a run for the front porch of the woman, Emma Stackhouse. Before he reached safety, a gunshot rang out, and a bullet struck Chester just above the left eye. Everything went black.

Chester survived the attack and later wrote about it in a letter to his mother. Witnesses relayed details to the press and police, and the Weekly National Republican went so far as to report that Pinchback “slapped [Stackhouse] violently on the face and pushed her down on the gallery steps.”

Pinchback issued a statement in the Louisianian denying that he attacked Chester or Stackhouse, though he admitted being at the scene and walking away after Chester rejected his support. A warrant was issued for Pinchback’s arrest, but in his new position as lieutenant governor, he was also president of the police board. Pinchback was never taken into custody, and another man took the rap for shooting Chester. He only served two days in jail.

It’s unknown whether the attack on Chester was retaliation for his Congo Square speech. The embers of doubt he lit regarding Dunn’s demise, however, couldn’t be so easily stamped out.

Historians A. E. Perkins and Marcus B. Christian revived the inquiry in papers published in the 1930s and ’40s. Christian’s “The Theory of the Poisoning of Oscar J. Dunn,” published in Phylon in 1945, concluded that “even though each clue must be examined with a great degree of caution, a careful weighing of evidence does not negate the Dunn poisoning theory.” Perkins interviewed a number of Dunn’s contemporaries. “The conspirators were known,” said one, a man named Edmund Burke, “but nobody dared speak out. It would have been unsafe.”

Perkins even sat down with Warmoth himself, not long before his death in 1931, and asked him directly about the rumors. “Yes,” Warmoth told him, “such a rumor was current, but the physicians attending him pronounced his death as due to natural causes.” Warmoth, Perkins wrote, “did not seem disposed to continue the conversation.”

The speech by Thomas Morris Chester and the Weekly National Republican articles detailing the attack on Chester are just a few of the newly uncovered sources revealed in THNOC’s graphic history, Monumental: Oscar Dunn and His Radical Fight in Reconstruction Louisiana, by Brian K. Mitchell, Barrington S. Edwards, and Nick Weldon.

Inset image: Thomas Morris Chester in 1870. (Image courtesy of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, the New York Public Library)