Danny Barker is remembered primarily as a banjo/guitar player and elder stateman of jazz, but he was also a committed writer and prolific storyteller. Barker began writing in the 1930s, during his years as a big band musician in New York City, and he continued for the rest of his life. By the time he died, in 1994, he’d published two books, contributed to other published works, sat for several oral histories, given countless interviews and storytelling appearances, and amassed a large collection of unpublished works that currently sits in the Danny and Blue Lu Barker Archive at Tulane University’s Hogan Archive of New Orleans Music and New Orleans Jazz.

In 1948 Blue Lu and Danny Barker relocated briefly to Los Angeles to pursue an opportunity with Capitol Records, resulting in this publicity photograph. With Blue Lu as his muse and vocalist, Barker channeled sex, violence, and humor, wrapped in the seductive pacakge of a blues mama. (Courtesy of Alyn Shipton)

Barker wrote about New Orleans, the music business, New York, racism and Jim Crow segregation, and the pleasures of dancing, drinking, and having a good time. Like his near-contemporary Zora Neale Hurston, Barker often approached his subjects through the framework of African American folklore, recasting events and people from his own life as folk archetypes. Tricksters, badmen, blues mamas, white devils, and everyday people living what he called the “raw life” all populated his oeuvre. Folklore, Hurston wrote, “shows the adaptability of the black man,” allowing each African American writer or storyteller to draw from a vast cultural well across time, place, and social status. Barker drew from that well time and again, blending history with autobiography and a dash of mythology and creating indelible characters in the process. Here’s a look at five of his biggest standouts.

1. The Badman: Joe Baggers, from A Life in Jazz

Joe Baggers was well known, and familiar with everybody in the seventh, eighth and ninth wards. When some upstart boy or girl entered the Animule Hall and Joe Baggers felt they were too young, he kicked them in the behind and chased or dragged them to the street, yelling, “Get out of here. You’re still pissing in your drawers.” That was very embarrassing, because everyone stopped dancing and laughed at you, even your relatives. But if Joe Baggers thought you were ready and able to protect yourself and let you stay in the hall, somebody was sure to challenge you before the hall closed that night, by stepping on your foot, by elbowing or by pushing your hat off (the men never removed their hats). . . . While the battle was in progress Joe Baggers always rushed to the center of the fracas and saw to it that the contestants fought man to man, or woman to woman. He kept the wild crowd a safe distance with his menacing iron pipe and he would yell to the frantic crowd, “Stand back! Let ’em fight! Don’t crowd ’em! Give ’em air! Give ’em a fair chance! Don’t nobody get in this humbug!” He would allow the fight to continue until one fell, badly beaten or exhausted. Then he decided who was the winner, and he would grab the loser and plant his long-pointed-toed shoe on the loser’s rear end. That was the process of departure.

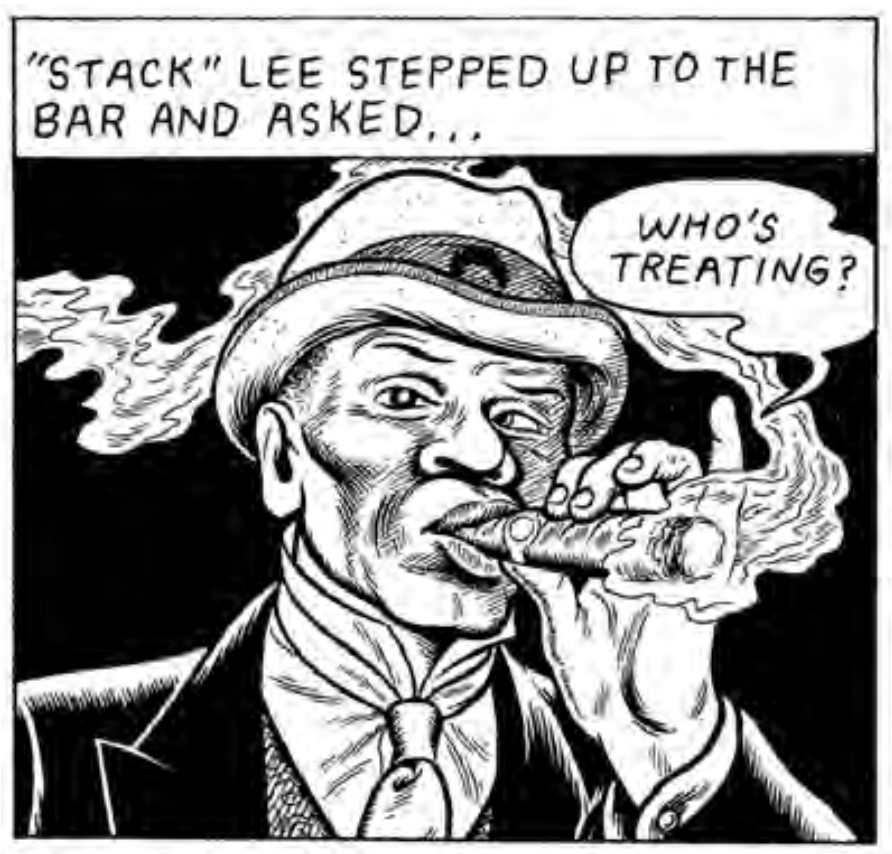

“Stag” Lee Shelton, better known as Stagger Lee or Stagolee or Stack Lee, as shown above, quickly became a folk antihero after murdering a man who allegedly grabbed his hat on Christmas Day 1895. The allure of the volatile badman has prompted dozens of artists to sing about Stagger Lee, and it can also be seen in Barker’s depiction of Joe Baggers, proprietor of the Animule Hall. (Illustration by Timothy Lane, from “The Story of Stagger Lee,” courtesy of Riverfront Times)

One of the central set pieces of Barker’s 1986 autobiography, A Life in Jazz, is the chapter titled “Animule Hall,” and Joe Baggers is its main character. At the hall, Baggers presides over a weekly cycle of drinking, “belly-rubbing,” dancing, and fighting, all interwoven with the blues music of Long Head Bob’s Orchestra. With his pointy-toed boots, iron pipe, and brutal ways of keeping the rowdy crowd in line, Baggers is a classic badman—one who transgresses “normative heroic action,” yet functions as a hero because of his ability to transcend the limitations of his station, according to John Willie Roberts in his book From Trickster to Badman: The Black Folk Hero in Slavery and Freedom. Like Stagger Lee or Railroad Bill, who became folk legends through their violent deeds, Joe Baggers is not to be trifled with. He is, in short, “a very rough man,” yet he is a stabilizing force when the hall’s blend of booze, blues, and brawling spins out of control.

2. The Trickster: Meatball Charlie, from “Mr. Meatball Charlie of New Orleans”

My Uncle Willie, who is two years older than I, says to me, “Danny, I’ve got a job for you if you want it. It’s depping [assisting] on Mr. Meatball Charlie’s peddling truck! . . . He is easy to work for but he never stops talking and bragging.” . . . He was never without his brown derby, which he wore cocked to the side of his head, and the suspenders, which held up his low-waisted pants. He kept his round head shaved, and a short, strong Italian cigar in the corner of his mouth. He rarely ever lit the cigar. I think he kept it in his mouth to give him an air of authority, because once he became absorbed in one of his many tales he would take it from his mouth, put it back as part of his routine of gesturing, as he described situations with his arms and hands. He could enjoy a laugh until tears came to his eyes and in a split second could become dead serious and hold a dead pan expression for minutes, until he’d have to laugh at himself. He had a great variety of voices that he used amusingly to heckle and annoy people.

In “Mr. Meatball Charlie of New Orleans,” Barker portrays himself as a boy working as a vegetable peddler’s assistant, traversing different areas of the city on a cart similar to the one seen here. (THNOC, 1976.176.4)

In the unpublished “Mr. Meatball Charlie of New Orleans,” Barker composes a vivid picture of 1920s New Orleans while using the title character as a framing device for several outlandish folk tales, such as “Jazzabelle and King Pharaoh in the Desert” and “Li’l David and His Fifteen Virgin Sisters.” Barker writes Meatball Charlie as a trickster, a fountain of tales, boasts, observations, and wordplay. Always greeted “like a big celebrity or gloom chaser,” Meatball Charlie is the life of the party, and his defining trait is his “diarrhea of the mouth.” Barker portrays him as a master of signifying—the African American art of performative double-play, which can take the form of braggadocio, insults, jokes, tall tales, or even fashion.

In one memorable sequence, Meatball Charlie takes young Barker to the funeral of a respected Confederate general as part of his sideline racket, stealing flower arrangements from fresh gravesites. When a white funeralgoer asks why they’re there, Meatball Charlie puts on his trickster guise and successfully evades suspicion by launching into a story about how his grandparents were enslaved on the general’s plantation and that he was the kindest, most generous master there could ever be: “That is why me and little Dan are here today with heavy hearts, paying our respects to a great man who’s surely going to Heaven.” Young Barker asks Meatball Charlie why he deferred to the man so easily. Meatball Charlie responds, “What I said, is not what I meant. . . . When you know you cannot win, be like a lamb. Remember that, my boy, and you will live to see another day.”

Though Barker asserted in 1974 that Meatball Charlie was a real person, his daughter, Sylvia Barker, shared a different take in her play adaptation of “Meatball Charlie,” calling him a “fictional character taken from the mind of Mr. Danny Barker.”

3. The Elder-Raconteur: Dude Bottley, from Buddy Bolden and the Last Days of Storyville

I said, “I would like to know what kind of a person Buddy Bolden was. What happened in Lincoln Park? . . . Why did Bolden lose his mind? What was the atmosphere of Lincoln Park? What kind of music did Bolden play? . . . Mr. Dude said, “That’s just as easy as eating pie. My bones are old, but my mind is young and I can picture everything I saw just like if it happened yesterday.” . . . Mr. Dude talked on and on. When he paused I would prompt him, and he’d continue talking. His niece, so full of New Orleans hospitality, demanded that we stop the recording and have supper. After the feast was over, she said, “I told you Uncle was a talking machine!”

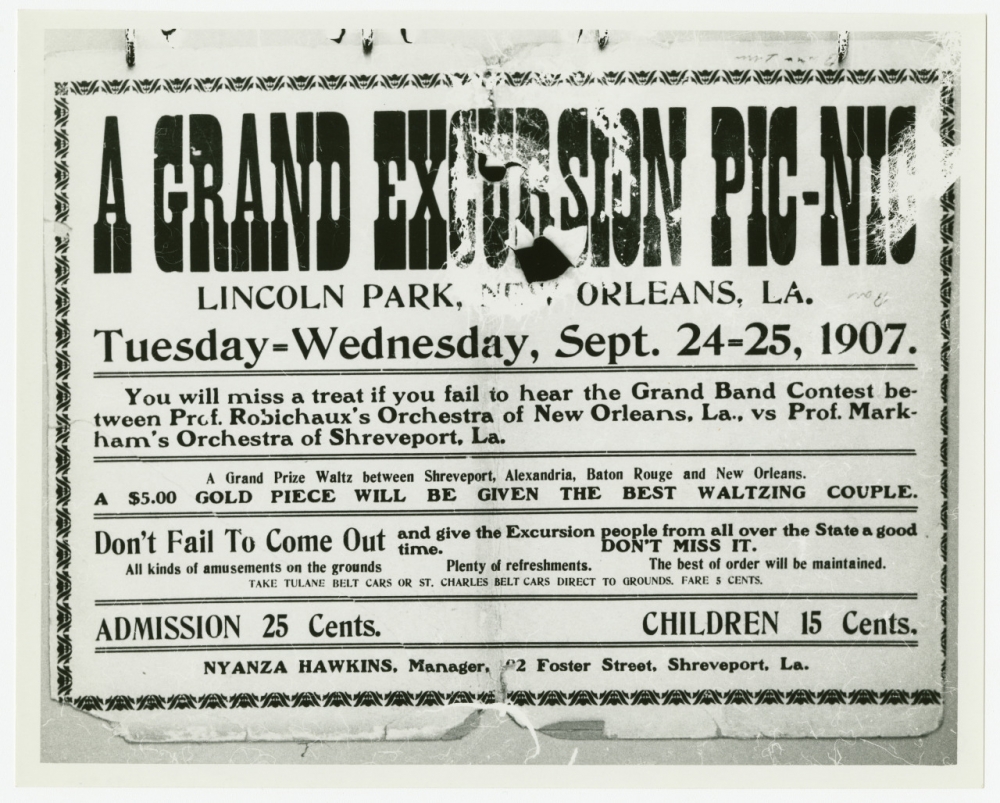

Lincoln Park, formerly located near Carrollton Avenue and Earhart Boulevard, has become enshrined in jazz history and lore for its association with the legendary cornetist Buddy Bolden. Bolden’s band would perform there for regular concerts and picnics, such as the one advertised in this handbill from 1907. Barker re-created the lively scene of these picnics in his book Buddy Bolden and the Last Days of Storyville. (THNOC, William Russell Jazz Collection, MSS 520.3406)

Barker grew up around first-generation jazz musicians such as his grandfather, Isidore Barbarin, who played mellophone in the Onward Brass Band. Always observant, Barker soaked up their stories and memories, and later on he conducted his own research, interviewing jazz elders through mailed questionnaires. It’s likely that these sources formed the basis of Dude Bottley, one of the central figures of Barker’s second book, Buddy Bolden and the Last Days of Storyville, published posthumously in 2001. Presented as the brother of Bolden’s bandmate Buddy Bottley, Dude Bottley is a portal to the past, telling of Jelly Roll Morton, greased-pig chases, and comically dangerous hot air balloon rides.

Bottley was a fictional device—“definitely Barker’s invention,” said Alyn Shipton, who worked with Barker to edit the volume. “Buddy Bottley was a real person, and Dude was a way to ground all of Danny’s material about jazz history in a single story.” David Chandler, who interviewed Barker for New Orleans magazine in 1974, compared Buddy Bolden to Mark Twain’s Life on the Mississippi, precisely because the two books employ fantastical stories and capital-C characters to make “geographical concepts (Storyville and the Mississippi) part of America’s folklore.”

4. The Badwoman: Barker’s blues songs for Blue Lu

If you don’t like my peaches

Don’t you shake my tree.

I got ways like the devil,

Born in the lion’s den.

And my chief occupation

Is taking other women’s men.

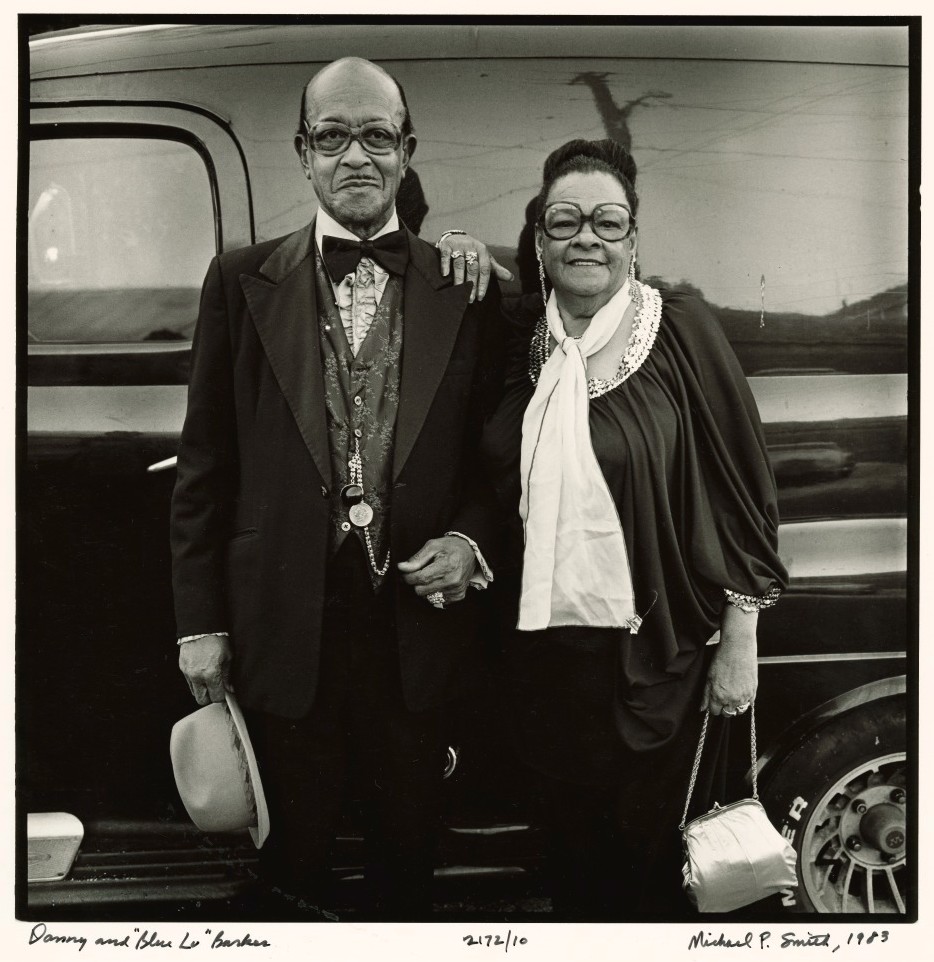

Danny and Blue Lu Barker, seen here in 1983, married in 1930, shortly before Danny left for New York to pursue a full-time career in music. “We set sail on the great ship jazz on the sea of matrimony,” he writes in A Life in Jazz. They remained married until his death, in 1994. (Photograph by Michael P. Smith © THNOC, 2007.0103.2.346)

As a songwriter, Barker had a muse in his wife, the singer Blue Lu Barker, who delivered these lines in the song “Ways Like the Devil.” He wrote a number of blues songs for her, scoring a minor hit with “Don’t You Feel My Leg,” first recorded in 1938 as “Don’t You Make Me High.” Through Barker’s blues songs for Blue Lu, he played with themes of sex, violence, and humor by wrapping them in the package of a transgressive badwoman. Like her brother the badman, the badwoman “flouts the norms of society . . . to gain the upper hand,” writes musicologist Ayana Smith. “The tradition embodies a narrative method of dealing psychologically with power struggles and lack of self-determination.” At a time when the popular imagination regarded Black women through the stereotypes of the subservient “mammy” or the oversexed, doomed “tragic mulatto,” blueswomen’s independence, irreverence, and authority imbued them with powerfully modern charisma.

Blue Lu said she knew even as a child that the blueswoman’s badness was a put-on—a form of signifying—and she maintained that opinion for the rest of her life. “Onstage, I say all these things,” she said in an undated radio interview. “I shake, I dance, I just have a good time. It would give you the impression that I’m a bad or fast person. But if you know me, you find out that I ain’t none of those things . . . not a real ratty person. I’m fun.”

5. The Unified Theory: Day People and Night People

New York clubs were the haunt of the crafty night people. They used to put on the act: set a trap to catch the day nine to five people. . . . It was a night when the place was empty. Everybody sat around like half asleep. At the door upstairs there was Ross the slick doorman. When he rang three loud rings on the upstairs door buzzer (it rang loud), it meant some live prosperous-looking people, a party, were coming in. Like jacks out of a box the band struck up “Lady Be Good.” Everybody went into action; the band swinging, waiters beating on trays, everybody smiling and moving, giving the impression the joint was jumping. (Fats Waller wrote a song, “The Joint is Jumping.”) The unsuspecting party entered amid finger-popping and smiling staff. (“Make believe we’re happy.”) This was kept up until the party was seated and greeted and their orders taken. Then on came the singers, smiling and moving; then another singer, a dancer. Then it was off to the races—action—“Let’s get this money.”

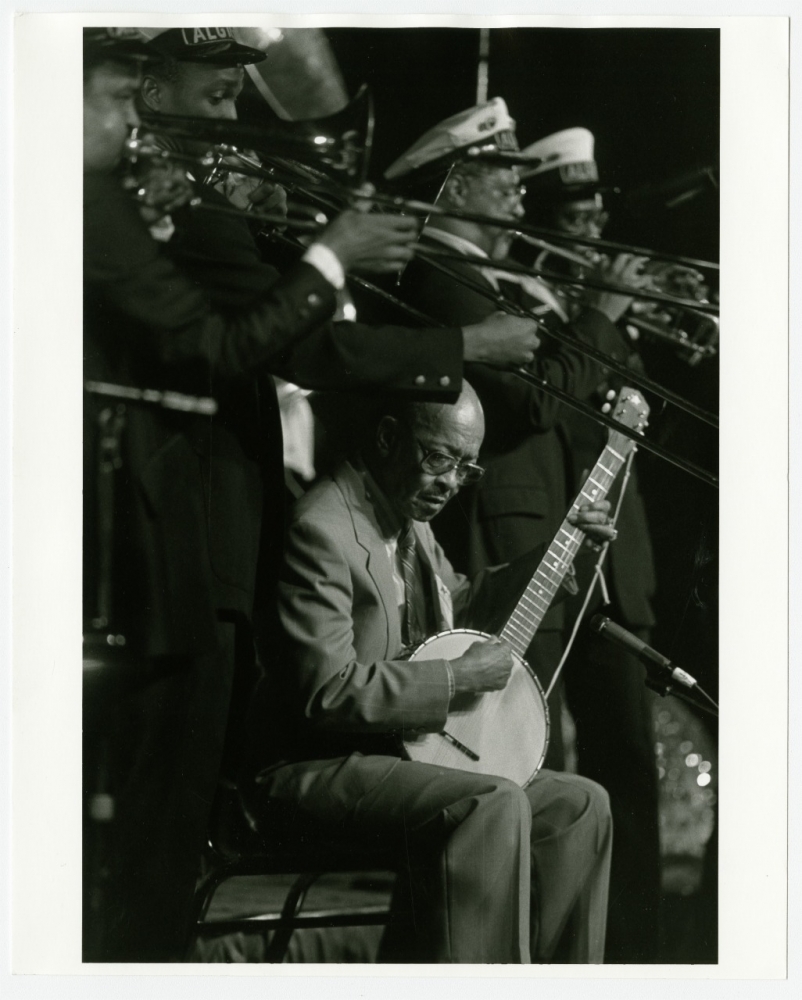

By the time he performed at the International Association of Jazz Educators in 1990, four years before his death, Barker had become something of a folk hero himself, known throughout New Orleans the jazz world as a raconteur, historian, and living link to jazz’s origins. (THNOC, gift of Tad Hershorn, 1998.84.8)

One of Barker’s most popular storytelling refrains, exemplified in the above passage from A Life in Jazz, was his theory of the two types of people in the world, “day people” and “night people.” On the surface, they were a shorthand for the vast difference in life experience between people with stable, conventional livings and the characters and workers of the underworld—bankers, housekeepers, and mechanics versus pimps, gamblers, and the jazz musicians who entertain them all night. Barker positioned himself as an ambassador to both worlds, and while he valued the upright respectability of day people, he championed night people as essentially more worldly: “Day people know very little about what happens with the night people,” he said in a magazine interview. “Night people have to know the day people because they live off them. Day people don’t really know them.”

This sense of unknowability resonated with Barker, who spent the first half of his music career as a sideman—one of 10 to 20 faces on a bandstand behind the main attraction, the bandleader. “A musician has much time to observe,” he said in a 1974 interview. “You watch the people who come in. What they do. Night after night. Seven days a week. . . . You see everything, because a musician is invisible.” By aligning himself with the rarely seen, unknowable night people, he transformed the grind of the musician’s life into a mystique. Through that mystique, along with his stories, music, historical work, and deadpan sense of humor, Barker became something of a folk character himself. His death on March 13, 1994, occasioned one of the biggest jazz funerals the city has ever seen, and musicians, fans, and scholars continue to celebrate his life and legacy through the annual Danny Barker Banjo and Guitar Festival.