The Decorative Arts of the Gulf South (DAGS) archive is a material culture initiative at The Historic New Orleans Collection concerned with digitizing, preserving, and disseminating research about decorative arts objects made or used in the Gulf South region before 1865. This summer, we worked as DAGS graduate fellows to catalog objects in the towns of Franklin, Jeanerette, Patoutville, and New Iberia along the Bayou Teche in south-central Louisiana.

Grace Ford-Dicks (left) and Fran Mahon, courtesy of Grace Ford-Dicks.

We are both students of material culture, a field of study that investigates the cultural, political, and economic meanings and associations found within objects. Studying material culture means learning from the everyday things humans make, use, and encounter. As the historian Tiya Miles asserts, “material objects operate as connectors between acted and felt aspects of existence” and between “two domains of lived experience” in the past and present. Objects physically connect us to the lives and experiences of past people and can be powerful sources of information that challenge and broaden our understanding of history as derived from the written archive. As Christine DeLucia explains, objects can be “vital sources of insight about topics that remain partial, elusive, or missing in written documentary records.”

As DAGS fellows, we documented objects in the field, referencing archival records and owners’ memories via interviews in order to produce short catalog reports on each object’s history. One component of this report is known as a provenance. Provenance, in its most basic form, tells us about an object’s life, beginning with an original owner or maker, to its present place today. A traditional object provenance offers information about the object’s name, material, date, place of origin (if known), maker (if known), and present owner. However, this brief report can leave out a lot of information about the object’s total history and risks framing the past solely through a lens of exclusive object ownership. Here, we seek to mitigate the effects of owner-centric histories by focusing on issues of labor and materiality, and expand object provenances to include histories long marginalized by the traditional archival record.

Memory and hauntings

“Memory” is a term used throughout the fields of decorative arts and material culture studies. Scholars define it much the same way as the general public: memories are the things we remember from the past—the stories, people, places, and things that we use to build histories about ourselves, communities, and nations. There are numerous ways we can engage with memory, from reading journal entries, to learning traditional and ancestral dances, to singing old songs. Memory is all around us.

Relying upon written memory (newspaper articles, journals, letters, etc.) to build an object provenance, however, often leaves out the voices of oppressed or marginalized people who are underrepresented in the paper record. When researching the Gulf South, this refers most often to both free and enslaved people of Native American and African descent.

These archival absences and historical erasures, what we refer to as “hauntings,” position luxury decorative arts objects, such as armoires, as solely inhabiting an elite, white, patriarchal world, imprisoning them within a history of plantation violence. Relying solely upon written records therefore reinforces white supremacist understandings of a haunted past that is seemingly devoid of Black and Indigenous life, culture, and memory.

To combat these blank records within written memory, we explored almost 50 years’ worth of established material culture scholarship, poetry, and art to understand how we might use artifacts to remember a past beyond the written word; beyond the planter’s pen. Inspired by our studies, we made materials and makers, not just owners, the center of our fieldwork approach.

An armoire’s story

Armoire; ca. 1850; mahogany, softwood, poplar, brass; provenance: Felicite Fortier (St. Mary Parish, LA); Peter W. Patout Collection; DAGS-2022-0001.

An armoire we cataloged during our fellowship offers a good case study for how we can reconsider traditional ideas of ownership. We first drafted a provenance in the traditional manner, focusing on ownership. It reads:

The armoire may have been purchased by Valcour Aimé on behalf of his daughter Felicité and her new husband Septime Fortier around 1850 for their plantation, Felicity. The object passed through the family and ultimately ended up with its present owner, a Fortier descendant.

This lineage presents an ostensibly straightforward story, but from one dominant perspective. Looking at provenance exclusively through the lens of white ownership limits our total understanding of the object’s material life and perpetuates longstanding historical inequalities.

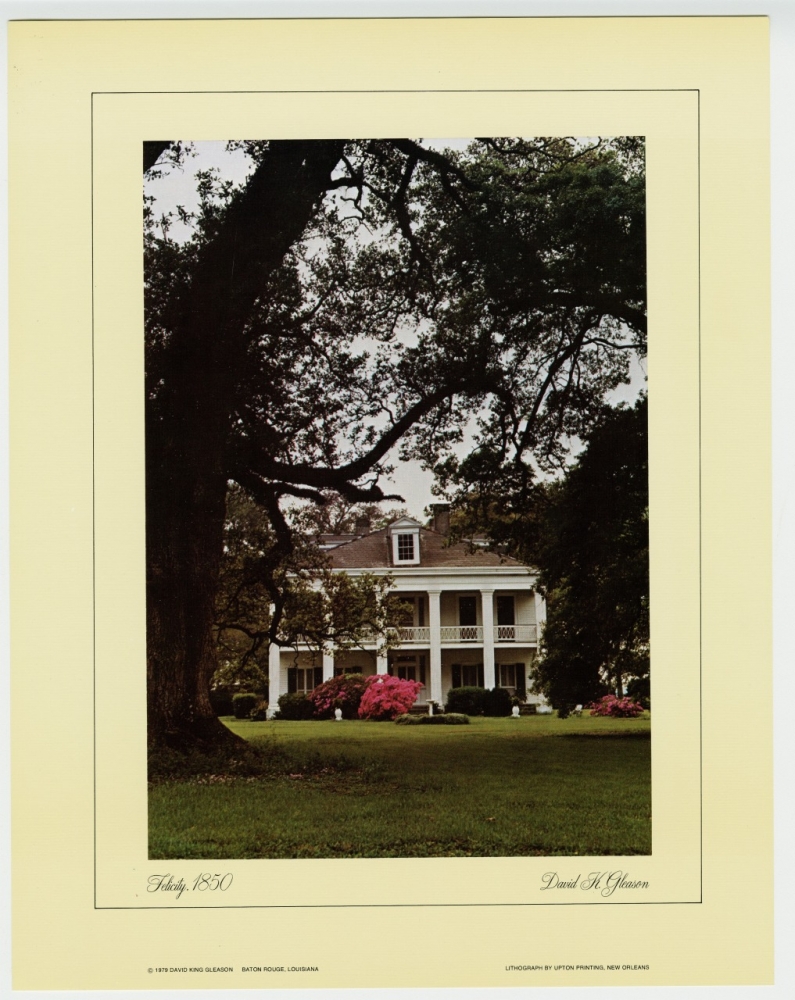

Felicity Plantation, home of the family that first owned the armoire. (THNOC, 2011.0304.1)

Focusing on materials pushed us to think differently about items like the armoire. It is made of mahogany, a luxury wood commonly used in 19th-century Gulf South furniture. Mahogany is indigenous to the Caribbean and Central America and was integral to pre-Columbian Native American landscapes and ecologies, colonial artisan workshops and warehouses, and post-colonial museums and mansions. The wood in Gulf South armoires was most likely a part of Indigenous American ecological landscapes and cultures, logged and cut by enslaved people of African descent, and joined by Eastern European immigrants in the mid-Atlantic. Focusing on materials therefore produces a much more nuanced, entangled, and multicultural history of the armoire.

We incorporate all of these groups in our provenance for the armoire by including Native American, African, and European words for mahogany and poplar.

Materials:

Caoba, M’Oganwo, mogano, mahogani, mahoń, swietenia mahogani, swietenia macropylla, mahogany

T’oo, amochool/hee/miinsh, topola, pappel, populus balsamifera, poplar

In addition to materials, we focused on labor. Enslaved people likely had as much access to and even more contact with the armoire than the white planters who owned it. Enslaved people’s hands cleaned, polished, moved, and opened and closed the armoire regularly.

The 1850 Slave Schedules, an additional census in which enslaved people were listed separately, records that Septime Fortier owned 54 people in St. James Parish, where Felicity Plantation was located. Though the record only states the age and gender of each individual, we can still learn a great deal. For example, the 28-year-old man listed within the Fortier household may have acted as a valet or butler, taking clothes out of the armoire as he performed Fortier’s morning dress routine. Five women between the ages of 14 and 32 listed within the household may have acted as maids or housekeepers, retrieving clothing or linens stored in the armoire.

Their labor and engagement left behind marks on the object’s history, memory, and material. It is these marks that we highlight in our new provenance for the armoire. It reads:

The armoire was produced around 1850 from woods primarily grown and cared for by the Taino, Carib, and Arawak peoples of the Caribbean Basin, alongside the numerous Haudenosaunee and Algonquian-speaking people of northeastern Turtle Island (North America). It was most likely cut and logged by enslaved individuals of African and Indigenous descent in the Caribbean Basin on mahogany plantations. After being cut the wood may have been finished and joined by enslaved or free Black craftsmen in the mid-Atlantic, or Eastern European immigrants in New England or the mid-Atlantic. It was cared for by enslaved individuals on the Felicity plantation from its time of purchase (c.1850) into the American Civil War. Although the armoire was purchased and owned by the Fortier family during the Antebellum era, formerly enslaved individuals may have continued to care for and engage with it into the twentieth century.

Continuing the work

Our provenance is an example of how the DAGS program can adopt a more complex approach to recording provenance that embraces the “ownership umbrella” of access, contact, and labor. This kind of approach builds on decades of critical archival scholarship and work done by museums around the country.

We thus build on the work of these historians, critical archival theorists, activist curators, and so many other voices when offering our framework for how the DAGS catalog can work to mitigate the erasure of traditional historical processes. Our work can serve as a productive tool for encouraging wide-ranging engagement with the Gulf South’s collective past. We offer this revised methodology as a first step toward redefining how the DAGS catalog and others like it interact with the past and future, with memory and hauntings.

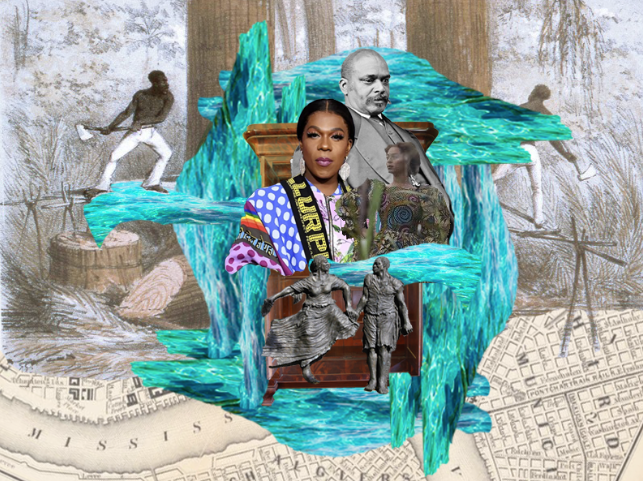

"Mahogany Symphonies 2," by Fran Mahon, courtesy of Fran Mahon.

This digital collage includes images of artists Big Freedia and Beyoncé as well as historic figures like Oscar Dunn, all of whom are connected to the history and culture of the region. Like Mahon and Ford-Dicks's new provenance, it entails a more multivocal past than a traditional provenance.

Some further reading

Anderson, Jennifer L. Mahogany: The Costs of Luxury in Early America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015.

Caswell, Michelle. Urgent Archives: Enacting Liberatory Memory Work. New York: Routledge, 2021.

Césaire, Aimé. Discourse on Colonialism. Translated by Joan Pinkham. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1972.

Delucia, Christine. "Recovering Material Archives in the Native Northeast: Converging Approaches to Traces, Indigeneity, and Settler Colonialism." Early American Literature 55, no. 2 (2000): 355-94.

Duff, Wendy M., and Verne Harris. "Stories and Names: Archival Description as Narrating Records and Constructing Meanings." Archival Science 2 (2002): 263-85.

Engle, Margarita. Hurricane Dancers: The First Caribbean Pirate Shipwreck. New York: Henry Holt, 2011.

Glissant, Édouard. Poetics of Relation. Translated by Betsy Wing. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2010.

Hartman, Saidiya. Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Hartman, Saidiya. "Venus in Two Acts." Small Axe 12, no. 2 (2008): 1-14.

Kincaid, Jamaica. A Small Place. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1988.

Miles, Tiya. "Packed Stacks and Pieced Quilts: Sampling Slavery's Vast Materials." Winterthur Portfolio 54, no. 4 (2020): 205-22.

Our Native Daughters [Rhiannon Giddens, Amythyst Kiah, Layla McCalla, and Allison Russell]. Songs of Our Native Daughters. Smithsonian Folkways Recordings, 2019.

Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. Boston: Beacon Press, 1995.

Turner, Hannah. Cataloguing Culture: Legacies of Colonialism in Museum Documentation. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2020.