1. Everything but Scarlet from Jim Flora’s New Orleans portfolio

(THNOC, 1970.18.16)

In Everything but Scarlet, James “Jim” Flora (1914–1998) presents a Southern plantation scene, with a large plantation house tucked into a lush landscape of trees. In the background, a man and woman in the dress of members of the planter class stand hand-in-hand, while two boys play in the grass. In the foreground, a barefoot Black man sings and plays the banjo. The title seems to be a reference to Gone with the Wind’s Scarlett O’Hara.

Flora included Everything in a collection of New Orleans–themed engravings commissioned by Union Central Life Insurance Company of Cincinnati. Flora had never been to the city when he created them, but the woodcuts resonated with a large audience. The engravings were so popular with readers that UCL released them as a limited-edition folio in 1942.

Banjos appear in two of the woodcuts from the New Orleans portfolio: Everything and the cover image. Other woodcuts from the set depict a stylized Jackson Square, a Black woman carrying flowers in a basket on her head, and a swamp scene whose title, The Eden of Louisiana, is probably a reference to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s Evangeline: A Story of Acadie.

From left: cover; “Flower Girl, N.O.”; “Jackson Square, N.O.”; “The Eden of Louisiana” (THNOC, 1970.18.1-11)

The New Orleans portfolio was one of Flora’s earlier commercial projects. Over his six-decade-long career, he created hundreds of works of commercial and fine art and wrote and illustrated 17 books for children. He is best known for the jazz and classical album covers he illustrated for Columbia Records and RCA Victor (now RCA Records) in the 1940s and ’50s. His graphically bold, iconic work helped to define the visual style of the 1950s and ’60s.

Examples of Flora’s cover art, clockwise from top left: Sidney Bechet, A Jazz Masterwork (Columbia, 1948); Kid Ory and His Creole Jazz Band, New Orleans Jazz (Columbia, 1947); Gene Krupa, Gene Krupa and His Orchestra (Columbia, 1947); Benny Goodman and His Orchestra, This is Benny Goodman and His Orchestra (RCA Victor, 1956); Louis Armstrong and His Hot Five, Louis Armstrong’s Hot 5 (Columbia, 1947); various artists, Mambo for Cats (RCA Victor, 1955)

A mix of cubism and modernism, Flora’s distinctive style is like Henri Matisse’s cut paper collages, but on acid. Flora’s vibrant contrasting colors are absent from the New Orleans portfolio, but aspects of his style are visible in the banjo woodcuts—the exaggeratedly stylized faces of the musicians recall his depiction of Louis Armstrong on a later album cover; the plants in the background of the engravings anticipate the swirling graphic shapes he later used to embody the energy of jazz.

2. The Boswell Sisters at the Orpheum Theater

(THNOC, gift of the Boswell Museum of Music, 2011.0315.94)

Though the banjo is typically associated with male musicians—Johnny St. Cyr, Danny Barker, Walter Wilcox—the Boswell Sisters broke the mold. Vet, Connie, and Martha Boswell were uptown New Orleans girls raised in a musical household and trained from a young age in the classical tradition. Brother Clydie played violin in a vaudeville orchestra and became well-versed in the emerging “hot jazz” style, passing on those rhythms and harmonic innovations to his sisters, who incorporated them into their singing. The Boswell Sisters’ close-harmony style made them stars of the early days of radio.

Before reaching national fame, they became local favorites, as seen in this photograph of the Boswells at the Orpheum Theater in 1925. Vet sits with her banjo, Connie at the piano, and Martha with saxophone. They were still in school at the time. Through such seated stagings in publicity images, Connie concealed her inability to walk, owing to a childhood case of polio.

In 2014 THNOC celebrated the Boswells with the exhibition Shout, Sister, Shout! The Boswell Sisters of New Orleans, and it remains on view online as a virtual exhibition.

3. Lobby card for It Happened in New Orleans

(THNOC, 2014.0102.61)

Originally released in 1936 as Rainbow on the River, this Kurt Neumann–directed film was rereleased under the title It Happened in New Orleans in 1945. Set in the decade after the end of the Civil War, the film tells the story of a young white orphan in New Orleans named Philip, played by famed “boy soprano” Bobby Breen. Philip is taken in and raised by Toinette (Louise Beavers), a formerly enslaved woman who is also a gifted singer and banjo player. A kindhearted priest tracks down Philip’s paternal grandmother, a wealthy widow who lives in New York and detests Southerners. Philip’s charm and cheeriness—and his skill playing that quintessentially Southern instrument, the banjo—eventually win over his Yankee grandmother, and she accepts him as a member of the family.

The film employs common racial—and racist—language and tropes of the era. It is Black characters, not white ones, who represent the backwards Old South. They speak in exaggerated dialect and are depicted as simpletons. Abraham Lincoln Stonewall Jackson George Washington Lilybell Jones (Stymie Beard), a self-described “pickaninny” who is friends with Philip, is so ignorant that he hates Yankees even though he is named after Union heroes. Rainbow on the River was released two years after Imitation of Life, which also starred Beavers as the complicated, well-rounded character of Delilah—arguably the first time a major Hollywood motion picture centered a story on a Black woman without reducing her to a one-dimensional caricature. In Rainbow, though, Toinette embodies the trope of the “Magical Negro” or mammy.

4. Banjo Clock

(THNOC, bequest of Boyd Cruise and Harold Schilke, 1989.79.1)

The body of this clock, which is on display in the Williams Research Center, is made of American mahogany. Its eglomise panels, made by back painting and gilding glass to give it a mirror finish, show a country mill and landscape.

(THNOC)

The banjo clock, so named because it’s shaped like the instrument, was patented in 1802 by famed Massachusetts clockmaker Simon Willard (1753–1848). Light and compact, Willard’s timepiece was dependable and affordable. An eight-day clock, it needed to be wound only once a week. Willard’s shop produced thousands of the clocks. He also shared his innovative design with other clockmakers, and the popular timepiece spread from New England across the nation.

“Banjo” doesn’t appear in Willard’s original ads, and he probably wasn’t thinking about banjos specifically when he designed the timepieces. The term caught on around the turn of the 20th century, in connection with the Colonial Revival. That movement helped establish a national consciousness in the US, connecting the country’s disparate cultural regions through shared architecture, design, and decorative arts. That the name “banjo clock” stuck not only in the South but also in New England and the Midwest is evidence of the cultural impact of banjos across the nation.

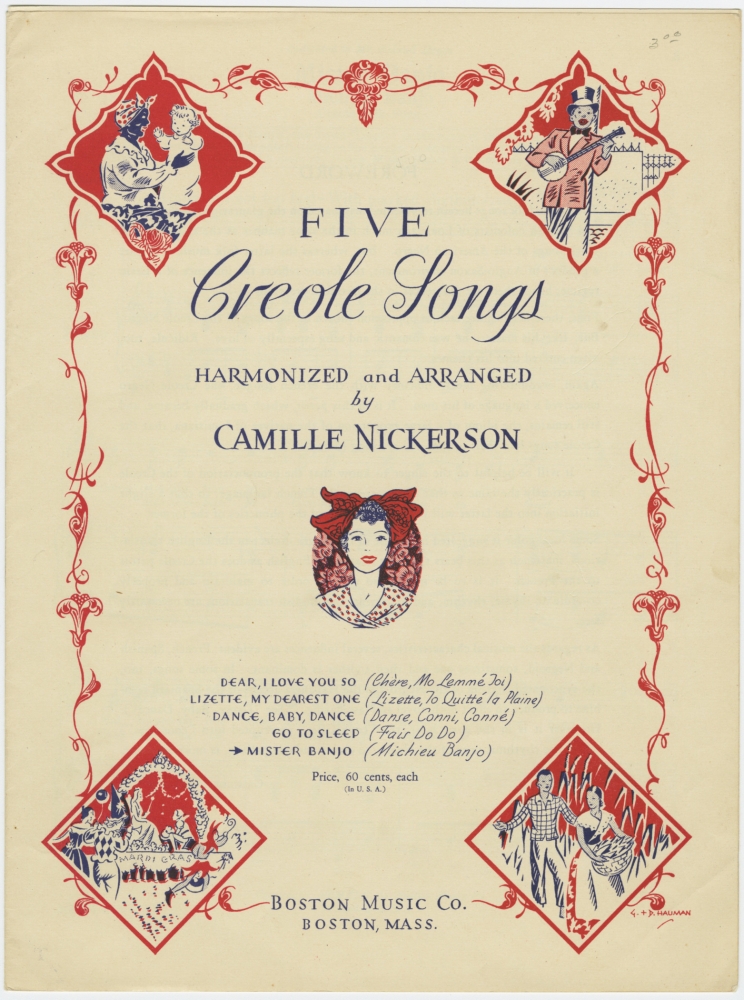

5. “Michieu Banjo,” from Camille Nickerson’s Five Creole Songs

(THNOC, 90-258-RL)

Also known as “Monsieur Banjo,” this is one of the Creole folk songs collected and arranged by New Orleans–raised folklorist and educator Camille Nickerson. The jaunty tune imitates the plucking rhythms of the title instrument, and the lyrics depict a dapper, cocksure man who dresses to the nines and struts down the street. This 1942 sheet music gives both the original French lyrics and English translation:

See that Mulatto over there, Mister Banjo, coming down the line

Hat turned on one side, Mister Banjo, walkin’ cane in hand

Smokin’ a big cigar, Mister Banjo, struttin’ to beat the band.

As Nickerson explains in a note accompanying the song, “Mister Banjo, the town dandy, is the envy of those who have neither his fine clothes nor his talent for entertaining on the banjo; moreover the envious pang is certainly not softened by the fact that he is a mulatto. Hence, Mister Banjo is the envy of much ridicule.” Indeed, at the end of the song, the narrator, having described every bit of Mister Banjo’s flair, describes him “ugly as homemade sin.”

In 2018, THNOC’s concert series with the Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra, Musical Louisiana: America’s Cultural Heritage, focused on music of New Orleans, with “Michieu Banjo” and another Nickerson arrangement performed by soprano Dara Rahming. Hear it below:

“Michieu Banjo” at “Music of the City” in 2018

Arranged by Camille Nickerson; orchestrated by Hale Smith; and performed by Dara Rahming with members of the Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra at St. Louis Cathedral

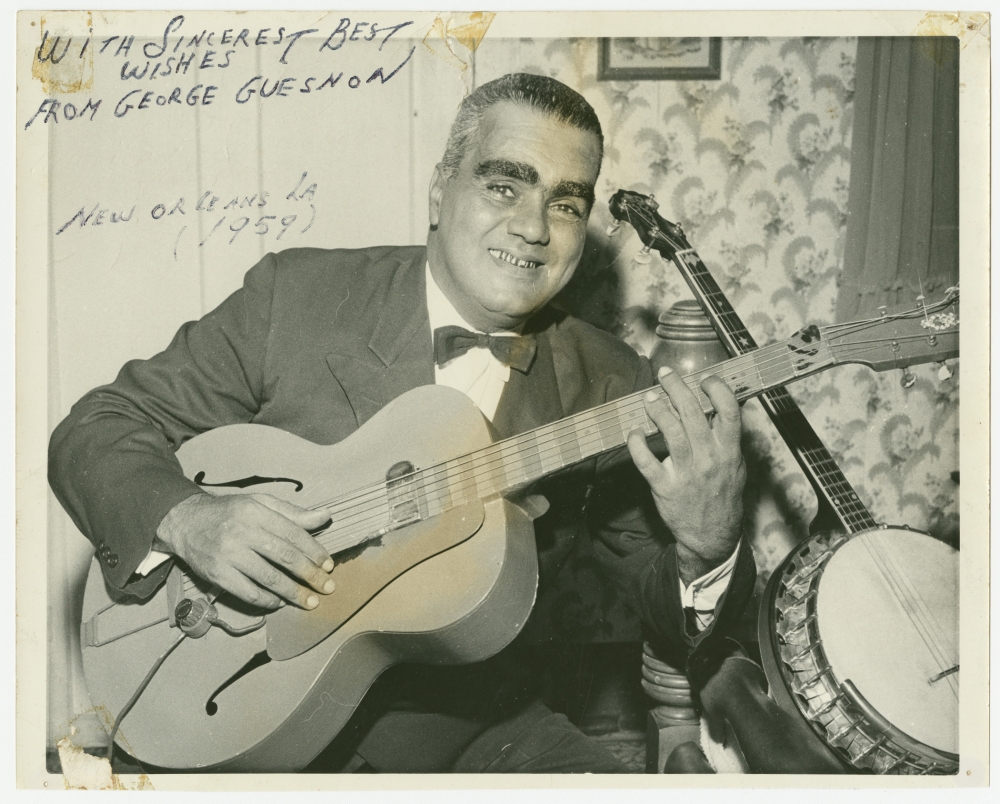

6. Interview and banjo lesson with George Guesnon

Banjo and guitar player George Guesnon in 1959 (The William Russell Jazz Collection at THNOC, acquisition made possible by the Clarisse Claiborne Grima Fund, 92-48-L.331.2853)

Trigger warning for anyone who grew up taking music lessons with less-than-prodigious aptitude: this recording of jazz banjoist George Guesnon giving a lesson to beginner Dick Talbert might make you want to hide in a dark closet. The recording was made by prolific jazz collector and researcher Bill Russell, who was friends with Talbert, a photographer for the Associated Press, in the 1950s. Russell helped arrange lessons for Talbert with legacy musicians, some with Guesnon and others with Manuel Manetta, a multi-instrumentalist who played violin, piano, trumpet, and saxophone in addition to banjo and guitar.

Born in 1907, Guesnon played banjo in the bands of Oscar “Papa” Celestin, Willie Pajaud, and Sam Morgan. In the 1930s, when many jazz bands switched from banjo to guitar, Guesnon kept on the five-string, touring with the long-running vaudeville troupe the Rabbit Foot Minstrels. In the 1940s he recorded with Jelly Roll Morton, and he found work with George Lewis and others during the traditional-jazz revival.

In his lesson with Talbert, Guesnon explains that playing banjo is about more than just strumming and counting. “It’s not what you play, it’s how you play it,” he says. “You can see a man, plays banjo 50 years, knows the chords, but he still can’t sit in with a band because what he plays is mechanical—it has no feel. You see, you got to have the beat.”

His pep talk dispensed, Guesnon tells Talbert to play “Basin Street Blues.” Poor Talbert isn’t two full bars in when Guesnon stops him: “No, no, no, no—you hear what you’re doing?” Guesnon cautions against “jumping” to chords—being choppy with the changes rather than smooth and sure-handed. Talbert makes another wobbly attempt, and Geusnon stops him again: “You got no beat.” Ouch. “You got all the chords in here,” he tells Talbert, after rattling off and playing every chord in the song in quick succession. “But it’s up to you to put 'em where they belong.”

Banner image: The Banjo sheet music cover, by Louis Moreau Gottschalk (THNOC, gift of Timothy Trapolin, 2000-92-RL.2)

About The Historic New Orleans Collection

Founded in 1966, The Historic New Orleans Collection is a museum, research center, and publisher dedicated to the stewardship of the history and culture of New Orleans and the Gulf South. Follow THNOC on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter.