“Coming to New Orleans” is a new series, presented in conjunction with American Democracy: A Great Leap of Faith, that tells stories of New Orleans immigration history through different items in our holdings. Read the first part of the series, a timeline that looks at New Orleans immigration in the context of immigration to the US, here.

Over the course of the first half of the 19th century New Orleans went from a small, largely ignored French colonial outpost to one of the largest and most profitable cities in the United States thanks to the growth of the cotton and sugar export industries. The population grew from less than ten thousand in 1800 to over 150,000 in 1860. In the 1840s, New Orleans was second only to New York City in the number of immigrants residing in the city, and by 1850 more than 50 percent of New Orleans’s population was foreign-born. Immigrants from Europe and the Caribbean contributed to this massive population growth as well as cultural, political, architectural, and commercial development.

Haitian immigrants

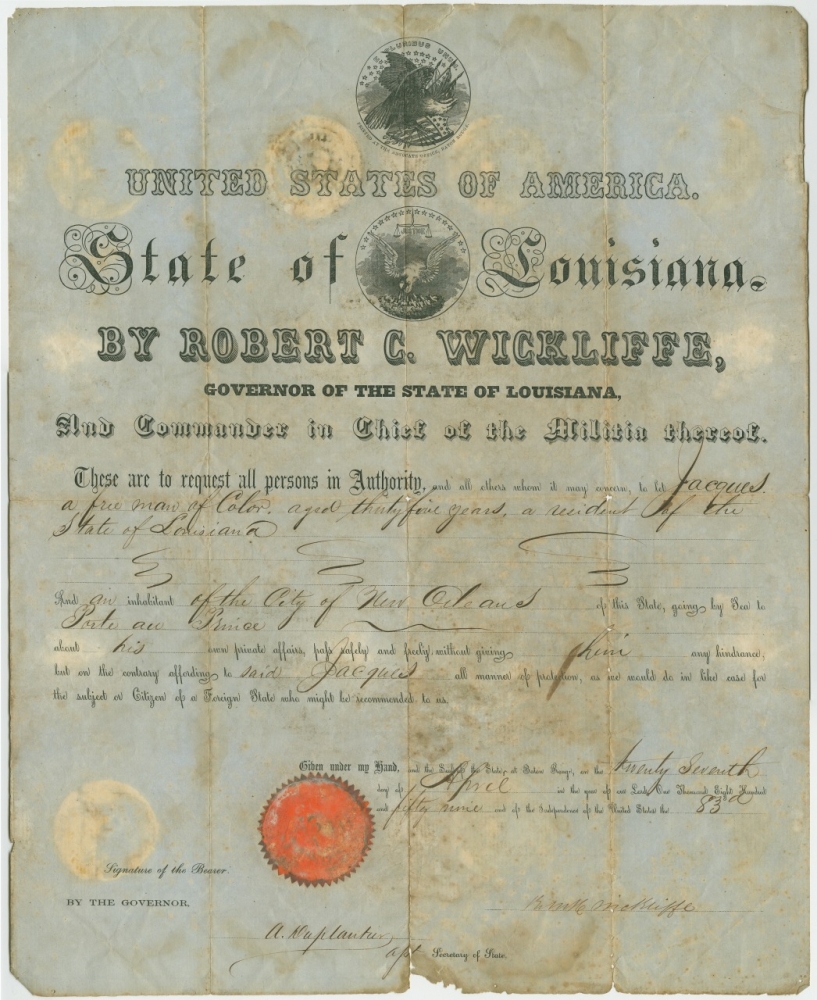

The passport of Jacques, a free man of color (THNOC, 95-28-L)

Thousands of immigrants from the French colony of Saint Domingue made their way to New Orleans during and after the Haitian Revolution at the turn of the 19th century. In 1809 and 1810, ten thousand of these refugees came to New Orleans, doubling the city’s total population and nearly tripling the population of free people of color. This growth also raised the profile and social power of the gens de couleur libre, who accounted for 25 percent of the city’s population by 1830.

This passport, signed by Gov. Robert C. Wickliffe and Assistant Secretary of State A. Duplantier, was printed in Baton Rouge and issued to Jacques, a 35-year-old free man of color residing in New Orleans, for travel to Port-au-Prince, Haiti, in April 1859. Though little is known about Jacques, this passport reflects the close connections between free people of color in New Orleans and Haiti. Jacques might have been a native of Haiti who was among the refugees of the Haitian Revolution, or he might have been a native of Louisiana with connections or interests in the island nation. It is also plausible that Jacques might have been one of the wealthy free people of color who left Louisiana for France and Haiti in the late 1850s as the gens de couleur libre community saw their rights being stripped away in Louisiana. By 1860, free people of color dropped to just 6.3 percent of the city’s total population. What is clear is that Jacques resided in New Orleans in 1859 and had reason to travel to Haiti. The United States did not formally recognize Haiti as a legitimate country until 1862. This passport’s usage of Haiti and not Saint Domingue is evidence that Louisiana had a closer relationship with the former colony than the rest of the United States.

Cuban immigrants

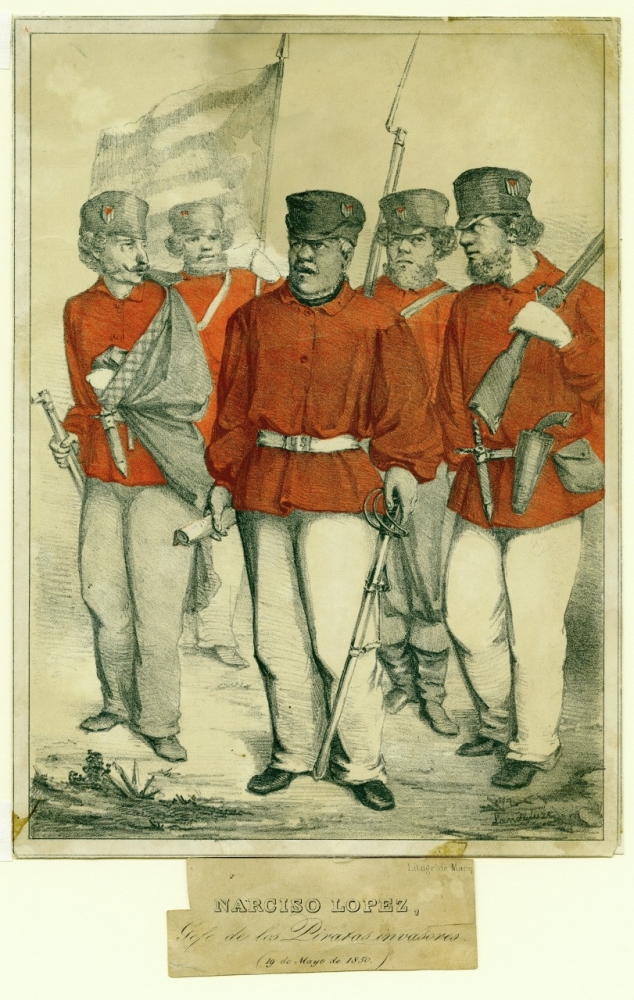

Narciso López and his piratas invasores (invading pirates). The lithograph originally appeared in a newspaper. It was later separated, partially colored, and sold in a Royal Street antique store before its acquisition by THNOC. (THNOC, 1978.123 a,b)

In 1849, Narciso López, a native of Venezuela and a former Spanish officer, initiated a campaign to overthrow Spanish rule in Cuba, largely in the name of strengthening the institution of slavery. Lopéz, along with Cuban sugar planters and businessmen, believed that slavery in Cuba was threatened by a weakening Spanish Empire, and only independence could ensure the institution’s survival. After his first attempt failed, López relocated to New Orleans, home to a growing population of Cuban immigrants, many of whom were sympathetic to his cause. After the Haitian revolution, Cuba and Louisiana emerged as major sugar exporters, and Louisiana adopted many Cuban sugar technologies such as ox-driven sugar mills. During the 1850s, the US government also had interest in annexing Cuba as a slave state, under the doctrine of Manifest Destiny. Many Americans who supported slavery, including a large number of Louisianians who owned sugar plantations in Cuba, had a vested interest in Cuba’s liberation from Spain.

López is depicted in this lithograph, originally published in a Spanish-language newspaper, with four of his supporters and the revolutionary flag. López launched two Cuban expeditions from New Orleans. He was captured and executed by the Spanish in Havana during the second expedition, in 1851. In New Orleans, López had enjoyed popular support among Anti-Spanish Cuban immigrants, pro-slavery Americans, and recently arrived immigrants who had fought in Europe’s 1848 revolutions. When news of his execution reached the city, his supporters violently attacked the Spanish consulate on Bourbon Street and pro-Spanish cigar shops. The flag that López designed became Cuba’s official flag when the country finally attained independence in 1902. The Daily Delta newspaper in New Orleans flew it outside of their offices in 1850, 52 years before Cuba became an independent republic.

Irish immigrants

Transverse section of St. Patrick’s Church (THNOC, 2008.0087.86)

St. Patrick’s Church, constructed in 1840, is the seat of the second-oldest Catholic parish in New Orleans. This architectural drawing of the transverse section of the church’s interior was drawn in 1837 by James Gallier, an Irish immigrant, with Dakin and Dakin architects. The drawing was intricately hand colored with watercolor to reveal stunning architectural details of the apse of the church. However, this apse design was never constructed. Charles Dakin died in 1838, and James Dakin was subsequently removed from the project, though he went on to build many Louisiana landmarks, including the Old State Capitol in Baton Rouge. Gallier took over the church project, and St. Patrick’s as it currently stands includes an apse of his design.

The arrival of the Irish from the 1830s to 1850s brought many new Catholics to the city. In most American cities, the arrival of Irish Catholic immigrants in the mid-19th century transformed the Catholic church, particularly in places like Boston and New York. In New Orleans, the church was controlled by ethnic French, whose brand of Catholicism was more lax than the Irish style. Unwilling to worship like the French, the Irish built their new church in Faubourg St. Mary. At the time, it was the city’s second district and had its own council and municipal services. The newly arrived Catholics selected a location on Camp Street almost the same distance from Canal Street as the St. Louis Cathedral on the downtown side of the thoroughfare. This signified the stark cultural divide between the English-speaking newcomers and old Creoles.

By the 1850s, as many as three new Catholic churches had been built, catering exclusively to English-speaking Irish Catholics. Yellow fever was particularly rough on newly arrived Irish immigrants, who were as much as 20 times more likely to die from the disease as Creoles. It is estimated that between six and ten thousand Irish workers died of yellow fever while digging the New Basin Canal in the 1830s, and in the deadly summer of 1853 one in five Irish immigrants died, so these new churches were likely the site of many burials and services for the dead.

German Immigrants

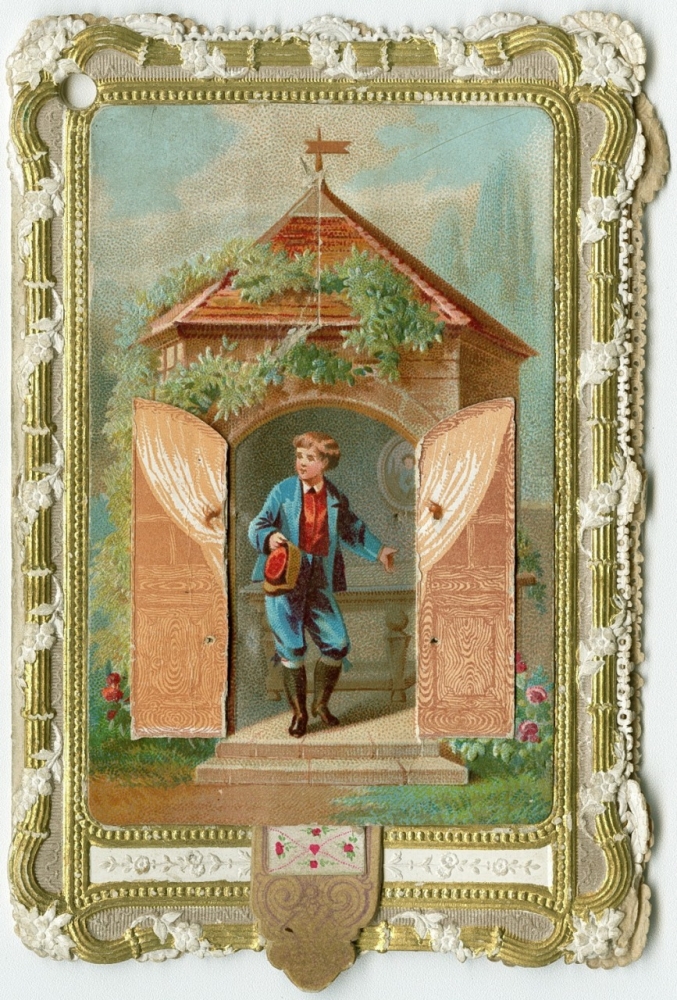

(THNOC, 2011.0303.2)

This 3-D pop-up card served as an invitation to an 1884 ball for members of the German Society of New Orleans, which was founded in 1847 to aid newly arriving German immigrants with work, shelter, childcare, and medical assistance. Germans had been coming to Louisiana since the 1720s, settling in an area that came to be known as the German Coast. Immigration from Germany greatly increased after 1840, with many settling in New Orleans thanks to the assistance of the German Society, or Die Deutsche Gesellschaft, which later merged with other German organizations to become the Duetsches Haus in 1928.

(THNOC, 2011.0303.2)

The ornate, multi-page invitation features a pull tab on the front that opens the doors of a cottage to reveal a young boy welcoming you inside. It was made using chromolithographic printing techniques and doily paper. The printer of the invitation is unknown. Lithographic printing firms first started opening in the city in the 1830s, and color lithography caught on in the 1850s. It is possible that this invitation was made in New Orleans, but its complexity and artistry indicate that it may have been made by a more well-established chromolithographer in New York or Paris. Well-funded carnival krewes, like the Mystick Krewe of Comus and Rex, often had their invitations printed by chromolithographers in Paris because of the perceived higher quality and status of having connections to Parisian printing firms.

Either way, the German Society’s access to these techniques reveals the wealth they had acquired by 1884. By then, German immigration had begun to slow down, and new arrivals required less direct monetary assistance. This excess in funds is reflected in the card, which was sent to all dues-paying members inviting them to attend a sumptuous ball at Grunewald Hall and Music Store, signifying their arrival in upper-class New Orleans society.

Jewish Central European immigrants

A Mardi Gras motif featuring cast iron and the store’s front façade decorate this mid-20th century paper bag produced for Godchaux’s Department Store (THNOC, 1999.50.51)

Among those fleeing the political violence of the revolutions that swept through Central Europe in 1848 were a large number of Jewish émigrés. Louisiana had been home to a population of Sephardic, Alsatian, and Bavarian Jews from Western and Central Europe since the French colonial period, making it a natural destination for some of these refugees. Blending in was of paramount importance to this group, who had faced religious persecution in Europe, and many of them quickly found a place in New Orleans society. In New Orleans, Jewish immigrants engaged in mercantile, shipping, retail, and wholesale occupations, with a Jewish business district emerging on Chartres Street by the early 19th century. With the arrival of Orthodox Jews from Eastern Europe in the 1870s, another Jewish business district emerged on Dryades Street in Central City, along with several Jewish schools and kosher establishments.

Leon Godchaux was a Jewish street vendor who arrived from Alsace in 1837 at the age of 13. He began selling goods from a wagon at rural Louisiana plantations before moving to New Orleans, where he opened a small dry goods store on Decatur Street. In the 1840s, he opened his now famous department store on Canal Street. Godchaux’s sold clothing and other goods and was managed and operated by family members for 150 years. Its façade, depicted on this circa 1940 shopping bag design made by commercial advertising artist Marjorie Clark, anchored the downtown shopping district at a time when Canal Street functioned as “the mall.” The company filed for bankruptcy in 1986, in part due to competition with other Canal Street department stores like D. H. Holmes and Maison Blanche. With the wealth he accumulated from his retail businesses, Godchaux purchased land and ran 12 sugar plantations in and around Reserve, Louisiana, earning the moniker “Sugar King of the South.”