Decorative Arts of the Gulf South (DAGS) is a cataloging and research project led by The Historic New Orleans Collection focused on decorative art objects made or used in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama before 1865. This summer, I interned with DAGS as part of my coursework in the museum studies program at Southern University at New Orleans, cataloging decorative and material culture artifacts in the heart of Acadiana.

Shadows-on-the-Teche, 2023 (courtesy of Lauren Goforth)

The project’s main focus this year was Shadows-on-the-Teche, a historic house on the grounds of a former sugar cane plantation in New Iberia. The house, built in 1834, has been open to the public as a plantation house museum since 1958. On our first day at the site, we encountered a massive armoire, crafted between 1830 and 1860 and original to the home. It is wonderfully Acadian and charming in its simplicity, with a beveled cornice, subtly curved skirt, and plain base. It is unusual in its number of recessed door panels, 16 total, of graduated size. This paneling recalls Renaissance cabinet forms, imparting a classical, architectural feel.

The paneling structure in this Acadian armoire shows Renaissance influence. It was originally painted with iron oxide gros rouge paint. (DAGS 2023-0002)

The armoire is constructed entirely of native cypress and, rather than varnished, painted with a brownish-red iron oxide paint known as gros rouge, traditional in Acadian furnishings. The ornamentation is minimal, except for the obvious—hand-painted Renaissance Revival columns, urns, and arabesques covering the doors. The interior is painted with flowers and vines. This decoration was added circa 1930 by William Weeks Hall, commonly known as Weeks Hall, the Shadows’s last private owner and great-grandson of its original owner.

Weeks Hall added this hand-painted decoration to the armoire around 1930. (DAGS-2023-0002)

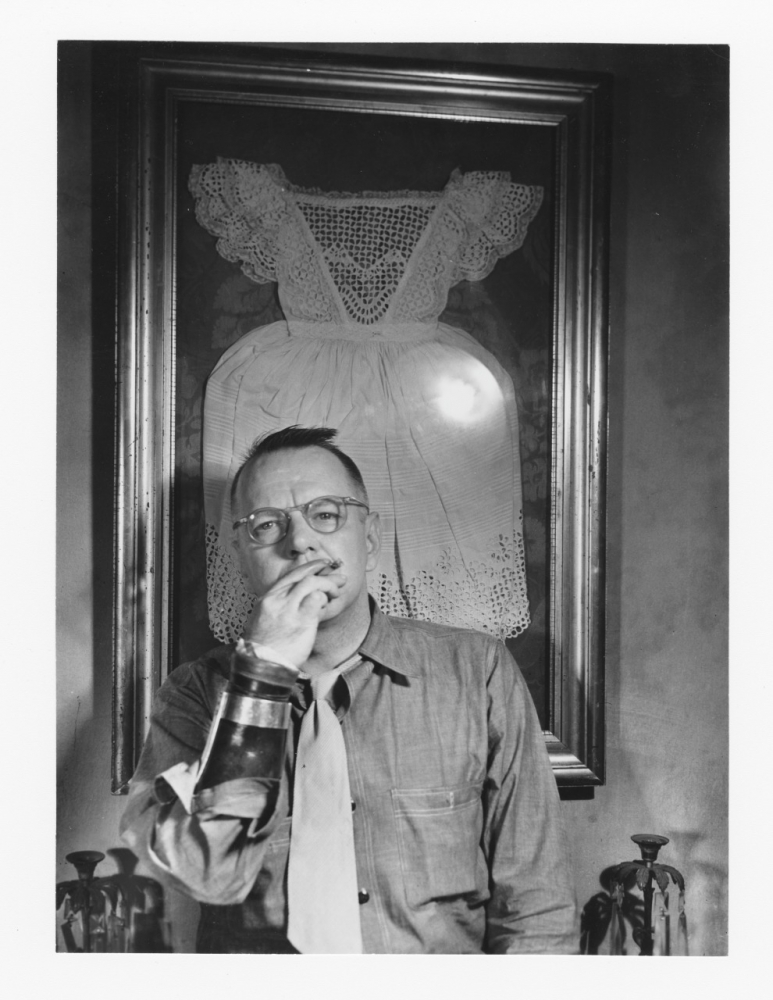

Hall was a painter, photographer, and well-known eccentric. He spent part of his childhood at the Shadows and part in New Orleans before studying art in Pennsylvania and Paris. He returned to the deteriorating Shadows for good in 1922, making it his mission to restore the family home.

Hall was, by all accounts, obsessed with the past—his own and the house’s—but his obsession came with contradictions. His ultimate goal was to entrust the property to a preservationist institution upon his death, so it could be open to the public. However, he closed it off to the outside world, planting a thick border of bamboo to shield the house from Main Street. His decades-long renovation project was careful to make only necessary, practical changes to the main house. Yet he demolished the original structures where enslaved people were housed, as well as the carriage house and stables, using their bricks as pavers in his new garden plan. Hall’s renovation preserved the main house but removed evidence of the enslaved people whose value and labor made the house’s existence possible. As the Shadows-on-the-Teche website puts it, Hall had transformed “a once functional, historic landscape into an ornamental one.” Weeks Hall died in 1958. He learned on his deathbed that the National Trust for Historic Preservation would take over the property, making the Shadows the first National Trust Historic Site in the Gulf South.

Weeks Hall, photographed at Shadows-on-the-Teche by Clarence John Laughlin (THNOC, 1983.47.4.568)

In many ways, the armoire mirrors the history of the site itself and reflects the different people who have called it home. The cypress wood it is constructed from has long been utilized by the Chitimacha and Attakapas tribes native to the region to build dugout canoes—essential for traveling the bayou that runs just behind the Shadows. While the armoire was owned by a wealthy white planter’s family, it was enslaved Black people who would have interacted with the piece most, opening and closing it to place freshly laundered linens within. Finally, it shows the hand of Weeks Hall, as does the entire site.

Shadows-on-the-Teche, circa 1900 (Courtesy of LSU Libraries Special Collections, Louisiana Digital Library, 1254_C-281)

About The Historic New Orleans Collection

Founded in 1966, The Historic New Orleans Collection is a museum, research center, and publisher dedicated to the stewardship of the history and culture of New Orleans and the Gulf South. Follow THNOC on Facebook or Instagram.