Prudence and decorum define the office of the presidency. But try telling that to George Washington.

The father of our country, coated head to toe in sugar, once climbed onto a table during revels at the St. Charles Hotel. Thomas Jefferson, not to be outdone, went skydiving over Lake Pontchartrain. And Ulysses S. Grant swigged from a jumbo bottle of beer while weaving his way down Canal Street.

Impeachable behavior? Scandalous hijinks? Hardly. Simply business as usual in New Orleans.

The Historic New Orleans Collection houses numerous political artifacts—broadsides, bills, editorials, proclamations—of serious import. Less weighty, but equally illuminating, are the menus, postcards, badges, and other ephemera that illustrate the lighter side of politics. Among the liveliest are those documenting presidential visits to New Orleans.

President William McKinley saluting passing boats in a river parade. (THNOC, 1989.9i,ii)

Consider the stash from William McKinley’s May 1901 swing through Louisiana—photographs, banquet programs, souvenir ribbons, and mouthwatering descriptions of 11-course feasts. The first president to visit New Orleans during his term in office, McKinley spent three days being fed and feted. The president ventured some formal remarks on trade (and the benefits, for the port of New Orleans, of an “open door policy” with China), but festivity was the real business of the day. One man on the street, quoted in the States, summed up the situation: “E is de g-g-g-r-r-r-eat President of those Etats Unis what come to Noo Orleans for eat those fine crayfeesh bisque, yes!”

McKinley and his entourage toured the Cabildo, met with a “colored” delegation from Southern University, and paraded through the flag-draped streets of the city. “As far as the eye could see,” observed the Times-Democrat, “New Orleans was a shimmering, fluttering, floating bouquet of beauty . . . by the side of which the glories of Mardi Gras paled into insignificance.” Only one minor mishap—a mix-up over harbor jurisdiction—marred the visit, forcing a brief delay in the “River Parade” and exposing Mrs. McKinley to the midday heat. Nautical misadventures notwithstanding, the president told the press, “My visit has been delightful,” and vowed to return soon. Four months later, he was dead, the victim of an assassin’s bullet in Buffalo.

Nearly every president since McKinley has fit a New Orleans junket into his schedule. Teddy Roosevelt came for a banquet—and returned for a bear hunt. Dwight Eisenhower came for the sesquicentennial of the Louisiana Purchase. John F. Kennedy came for the dedication of the Nashville Avenue Wharf. Jimmy Carter came for the Sugar Bowl.

New Orleans welcomes President-elect Taft. (THNOC, 1977.10)

Despite the conveniences of modern air travel—JFK winged in and out of town in under three hours—early travelers enjoyed certain advantages. Perhaps because they worked harder to get here, most stayed on longer, and played harder, on arrival. William Howard Taft, who wended his way to New Orleans by train, cruiser, and carriage, enjoyed a three-day blowout in February 1909. The president-elect headed up a gala parade; joined the Elves of Oberon at their Carnival ball; greeted 3,000 Black schoolchildren at Pelican Park; enjoyed a golf outing with leading citizen Philip Werlein (whom he edged out by one stroke on the front nine, three strokes on the back); and attended a grand banquet at the Hotel Grunewald. A menu card from the banquet is awash in high spirits—Amontillado to complement the Crabes Pontchartrain and Gombo Nouvelle Orleans; Liebfraumilch to accompany the Casburgot Chambord, Pommes de terre Brabançonne, and Poulet Créole; and Chateau Lafitte and Louis Roederer Brut to go with the Ananas au Marasquin, Sarcelle Farcie aux Noix, and Champignons Frais. After dessert (Pralines de Coco, Petits-fours, Biscuit Glacé, and Gateau au Gingembre) came cognac, cigarettes, and cigars. “Perhaps some of the survivors this morning may wake up with headache, but it is earnestly hoped there will be no heartaches,” quipped the Daily Picayune. On Taft’s departure, well-wishers showered his railroad car with bouquets, bonbons, and live possums. “Not only have I had the time of my life,” the president-elect told reporters, “but, to use a colloquial expression, it has been a red-hot time.”

President Taft plaing golf with Philip Werlein (THNOC, 1974.25.27.422)

Taft’s predecessor in (and later rival for) the presidency, Teddy Roosevelt, visited Louisiana in 1905, 1907, and 1911. Locals arranged the obligatory banquets—at the St. Charles in 1905 and the Grunewald in 1911—but also staged activities in keeping with the president’s preference for a “strenuous life.” Throughout the late summer and early autumn of 1907, southern sportsmen jostled for the privilege of accompanying Roosevelt on a bear-hunting expedition. Rumors flew as first one site, then another, was floated as a preferred destination. Attorney Lemuel P. Conner proposed a site in Concordia Parish, near Bayou Cocodrie. Roosevelt eventually pitched camp further north, along the Tensas River, spent two weeks in the woods, and—with the help of a renowned Black hunter named Holt Collier—found his bruin, but famously spared its life (giving birth to the Teddy Bear phenomenon).

Nearly a century later, Louisiana remains a sportsman’s paradise and—as former Vice President Cheney and Justice Scalia can attest—a mecca for high-ranking hunters. But in the end it’s the food, not the sport, that keeps visitors coming back. Every self-respecting restaurant, in and out of the Quarter, can trot out a story about the time the president came calling. Perhaps the most famous such anecdote features Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who in 1937 dined at Antoine’s with a party of local dignitaries. As Roosevelt supped on oysters Rockefeller, Mayor Robert Maestri leaned over and asked, “How ya like dem ersters?” Ronald Reagan was so enamored of Brennan’s bananas Foster that he requisitioned 11,000 servings for his 1984 inaugural celebration. George H. W. Bush popped into Arnaud’s during the 1988 convention, for a quiet dinner en famille. Bill Clinton feasted on crawfish gazpacho and catfish pecan meunière, courtesy of the Palace Café, in 1996. When Barack Obama visited the city in 2009 and 2015, he made time for culinary side quests: Leah Chase’s gumbo at Dooky Chase’s; red beans and fried chicken at Willie Mae’s; a shrimp po’boy, dressed, at Parkway Bakery.

New Orleans, beloved of tourists, freely dispenses love in return. For inaugurating the tradition of presidential visits, William McKinley will always hold a special spot in the city’s heart. But two other, earlier presidents—with Louisiana ties can also claim pride of place.

(THNOC, 1982.11)

Andrew Jackson, “Defender of New Orleans,” returned to the city in 1840, the 25th anniversary of his great military triumph. The 72-year-old stepped off a steamboat and continued, by carriage, to the Place d’Armes, where he was saluted by both veterans and civilians. Too frail to visit the battlefield at Chalmette, Jackson spent most of his five-day stay resting in a hotel suite at the St. Louis Exchange. He ventured out to lay the cornerstone on his equestrian statue; and he sat, in his chambers, for portraitist Jacques Guillaume Lucien Amans.

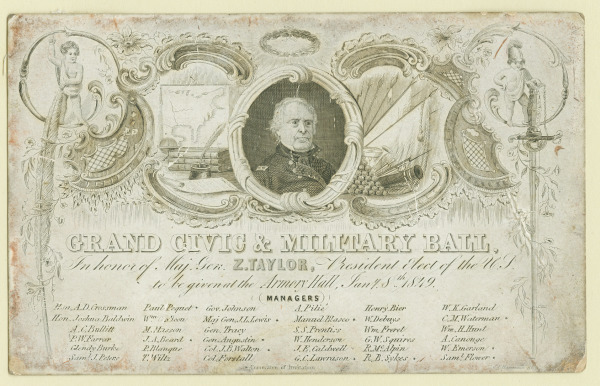

Virginia-born military hero Zachary Taylor adopted Louisiana as his home. In December 1847, fresh off his triumphs in the Mexican-American war, Taylor was toasted at a “corporation dinner” at the St. Charles Hotel. A year later, Taylor was tabbed as president—and New Orleans bustled to arrange a fitting send-off. To the dismay of all, a cholera epidemic forced the event’s postponement to January 25. By then, Taylor was already en route to Washington for his inaugural.

An invitation to a Grand Civic and Military Ball honoring Taylor (THNOC, 1956.29)

And what of Washington, Jefferson, and Grant? Truth be told, their visits owe more to artifice than actuality.

On December 14, 1799, Washington passed away at his Mount Vernon estate. On December 26, 1855, the Keystone Association of New Orleans held a banquet at the St. Charles Hotel. A menu card identifies Washington—or a sugary facsimile thereof—as one of the “ornamental pieces of confectionary” decorating the dinner tables. Though dead, and granulated, Washington still had style; a reporter for the Daily Picayune enthused over the “exquisite” execution of the centerpieces.

If Washington was miniaturized for his visit to New Orleans, Jefferson was blown up—literally. A fireworks display during the sesquicentennial celebrations of 1953 featured “fiery portraits” of Louisiana Purchase deal-brokers Jefferson and Napoleon. (Dwight Eisenhower, who spoke at the Cabildo but skipped town before nightfall, made an unlikely third in the pyrotechnic trio.)

And Grant? He really did visit New Orleans during his presidential term—in the guise of a bug. The Mistick Krewe of Comus scored a Mardi Gras triumph in 1873 with a torchlit procession titled “The Missing Links of Darwin’s Origin of Species.” For the occasion, Grant’s visage was grafted onto the body of a tobacco grub. As if that weren’t indignity enough, Rex resuscitated the design in 1997, installing Grant-the-grub on a float and plopping a big bottle of beer in his paws. And there, on his float, we will leave him, bringing up the tail end of our parade of presidents.

(THNOC, 1997.39.12)

About The Historic New Orleans Collection

Founded in 1966, The Historic New Orleans Collection is a museum, research center, and publisher dedicated to the stewardship of the history and culture of New Orleans and the Gulf South. Follow THNOC on Facebook or Instagram.