Freemasonry refers broadly to a network of fraternal organizations devoted to self-improvement and mutual aid. Related groups, such as the Odd Fellows, Elks, Knights of Columbus, and many others, serve a similar purpose of bringing together men (and sometimes women) to better themselves and their communities. Masonic groups are organized by lodges—the word refers to both the chapter itself and the physical space for the chapter. Members progress through a series of degrees and optional side orders, both replete with named roles and insignia.

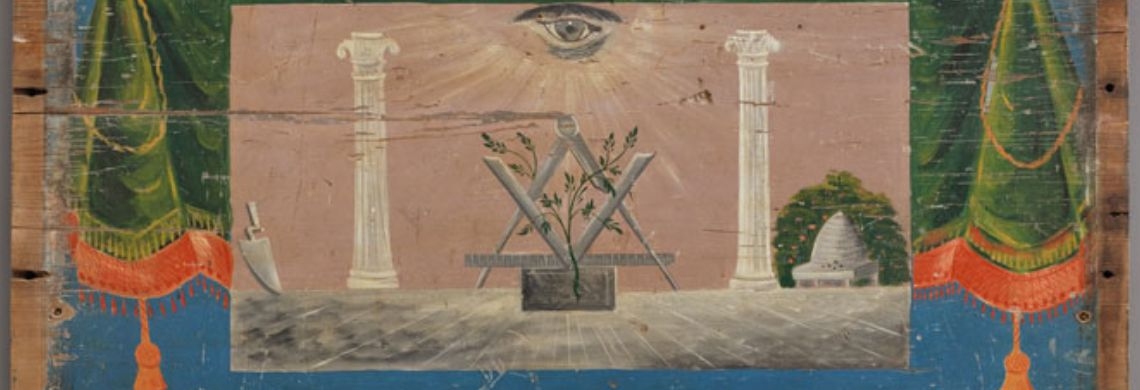

A Masonic sign made in 1871 (courtesy of the American Folk Art Museum, New York, gift of Kendra and Allan Daniel)

“Fraternal comes from the Latin word for brotherhood, and that’s what they’re about,” says Family Historian Jari C. Honora, who co-curated THNOC’s exhibition A Mystic Brotherhood: Fraternal Orders of New Orleans exhibition with Chief Curator Jason Wiese. “The Freemasons, as they say, ‘make good men better,’ by offering a series of progressive degrees that each come with some sort of moral lesson. By engaging with the degree work, it inculcates a stronger sense of brotherhood—not only among the members, but also with their families and communities.”

Freemasonry stretches back to the 16th-century British Isles, when skilled craftsmen like stonemasons formed working guilds and built lodges to offer shelter and fellowship to members traveling from job to job. “That’s why, to this day, Freemasons and other fraternal orders have this idea of being ‘at work,’” Honora says. “That’s why a lot of the regalia involves an apron, as well as the square and compass. All of those are working tools of a stonemason.”

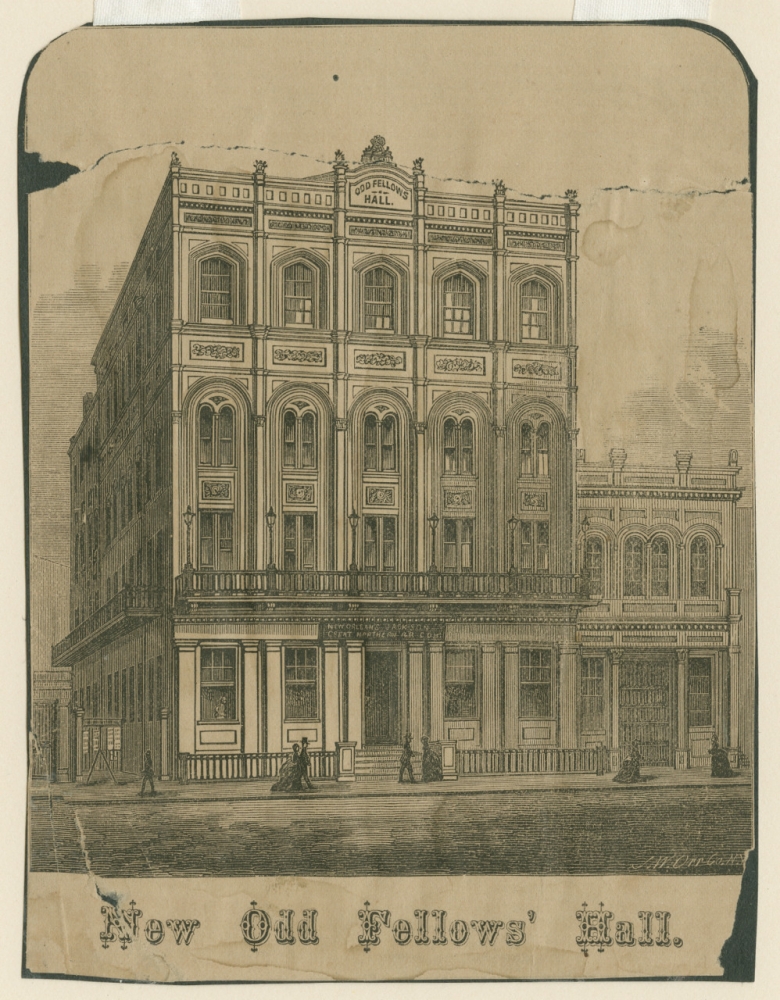

Constructed in the 500 block of Camp Street between 1867–1868, the New Odd Fellows’ Hall replaced the previous Odd Fellows’ Hall, which burned down in 1866 (THNOC, 1974.25.3.274)

Freemasonry reached New Orleans in the early 18th century, with the formation of the Loge Parfaite Harmonie (Perfect Harmony Lodge) in 1752. A Mystic Brotherhood features a proposal, dated 1756, for another Masonic outfit, the Loge d’Elus Parfaits (Lodge of the Perfectly Elect), which offered continuing work beyond the three degrees (tiers) of typical Masonry. The Odd Fellows—so named because they comprised workers of “odd” jobs that didn’t already have a guild—arrived in New Orleans in 1831.

Regalia and symbology run deep in the world of Freemasonry and Odd Fellowship. “These objects may seem mystifying to the uninitiated—but that is often the intent,” reads a text panel introducing visitors to Mystery and Benevolence: Masonic and Odd Fellows Folk Art, a show on loan to THNOC from the American Folk Museum. “Designed to instill a sense of wonder, the works on display embody a deep faith in fellowship, as well as in the potential for mystery and ritual to create lasting bonds.”

Masons’ use of iconography has its roots in European medieval artwork and 16th-century bestiaries and emblem books. These were popular illustrated books that matched pictures to certain tropes, values, or lessons. Many of the symbols found in emblem books—scythes, skulls, beehives, hourglasses—appear in Masonic and Odd Fellows art. The prototypical design of Masonic halls is based on principles of sacred geometry, and Masonic rituals involve the precise arrangement of symbolic items. These rituals typically happen in the hall’s sanctum, which bears a black-and-white checkerboard floor, symbolizing good and evil.

Assorted regalia (courtesy of the American Folk Art Museum, New York, gift of Kendra and Allan Daniel, photo be José Andrés Ramírez)

Regalia on display in A Mystic Brotherhood includes an Odd Fellows medallion from 1890, a Masonic apron presented to an initiate of Louisiana Lodge No. 102 in 1924, and a member’s signet ring from the mid-20th century. In Mystery and Benevolence, visitors can see a painting hidden on the underside of a chest lid that depicts the Masonic square and compass, symbolizing reason and faith, flanked by two pillars and, above, the all-seeing eye of judgement, or Eye of Providence.

Stacked with history, symbology, and a dash of mystery, fraternal organizations became a primary social outlet for men through the mid-20th century. By 1900, approximately 30 percent of all men in the United States belonged to at least one group. “Unfortunately, even though they espouse brotherhood, most of the groups in this country were segregated by race,” Honora says, explaining how parallel groups emerged along the racial divide. The first Black Masonic group in the Deep South, Richmond Lodge No. 1, was organized in New Orleans by free men of color in 1849. The Independent Order of Odd Fellows was predominately white, so Black men formed a separate group, the Grand United order of Odd Fellows, in 1843. The Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks were white, so men of color came up with the Improved Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks of the World.

Members of the Improved Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks of the World in 1949 (THNOC, The William Russel Jazz Collection, acquisition made possible by the Clarisse Claiborne Grima Fund, 92-48-L.331.1898)

As the popularity of fraternal orders grew, so too did the number of orders and side orders (branches with their own degrees and regalia—the Shriners, a Masonic side order, are a well-known example). “Once you get into the 19th century, all the way up through the first decade of the 20th century, you have a proliferation of fraternal organizations,” Honara says. “You have the Elks. You have the Moose. You have the Knights of Pythias. You have the Knights of Columbus, which is for Catholic men. You have the Knights of Peter Claver, which is for Black Catholic men.”

After the end of World War II, participation in fraternal organizations began to drop off, as increased American wealth gave rise to leisure activities, offering more opportunities for entertainment and edification. Though their numbers have decreased, the groups persist, both in New Orleans and beyond. According to Honora, the Elks have approximately 45,000 members nationwide, and the Knights of Peter Claver have about 16,000. “The good thing is, their purpose has remained unchanged,” he says. “It’s still to make their members better men—and women, because some of them are coed. It’s to do good in the community and support their members. Some of them provided burial benefits—cemeteries for members and designated plots.”

Honora likens fraternal organizations to social science’s concept of “third spaces”—places that are neither work nor home where people can gather, in person, for fellowship. In an increasingly online world, those kinds of gathering spaces are becoming rare. “Our moms, dads, grandparents, they had a lot of third spaces—church, gardening clubs, bowling clubs, civic associations,” Honora says. “Now, the number-one space is the coffee shops. But how many people do you see striking up conversations in the coffee shop? Not many.”

The Knights Templar on parade on Canal Street in 1922 (THNOC, gift of Mrs. Thomas Lennox, 1986.194.23)

To learn more about Freemasons and Odd Fellows, visit A Mystic Brotherhood: Fraternal Orders of New Orleans (on display from December 8, 2023 to May 10, 2024) and Mystery and Benevolence: Masonic and Odd Fellows Folk Art (on display from February 16, 2024 to May 10, 2024).

Header image: A chest lid with Masonic painting (Courtesy of the American Folk Art Museum, New York, gift of Kendra and Allan Daniel)

About The Historic New Orleans Collection

Founded in 1966, The Historic New Orleans Collection is a museum, research center, and publisher dedicated to the stewardship of the history and culture of New Orleans and the Gulf South. Follow THNOC on Facebook and Instagram.