It’s not unusual for the Tennessee Williams Annual Review (TWAR) to introduce never-before-published works from the celebrated playwright’s archives, but the poem that appears in the 2024 edition, due out March 22, presents a particularly intimate portrait. “The Final Day of Your Life,” now in print for the first time, is a moving poem about the death of Williams’s life companion of 15 years, Frank Merlo. Copyright restrictions prevent us from reproducing the poem here on First Draft, but copies of the journal are available for purchase online or in person at The Shop at The Collection.

Thomas Keith, who has edited Williams’s work for New Directions Publishing for over 20 years, brought the poem to TWAR and contributed an introduction setting the poem in the context of Williams’s life and work and of mid-20th-century US views on homosexuality. Below, Keith answers some questions about the poem, about Merlo, and about the crucial, once-invisible relationship with the playwright now getting its due.

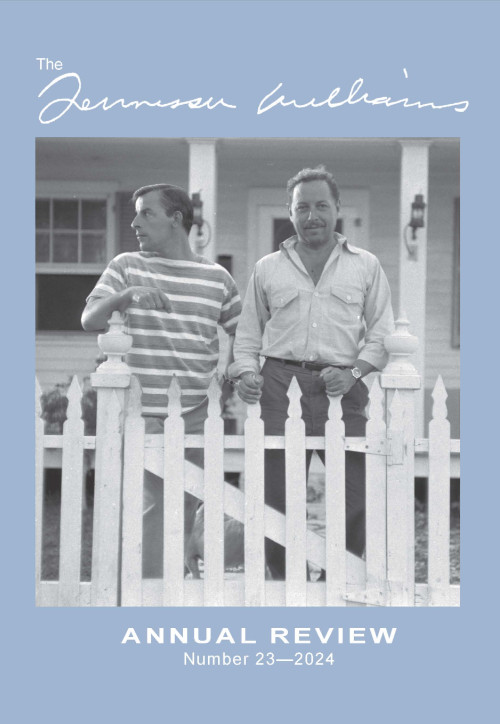

The cover of TWAR 2024 features a photograph of Frank Merlo and Tennessee Williams taken in 1958 when they were living together in Key West, Florida. (Photo by John Vachon for Look magazine; courtesy Library of Congress, LC-L9-58-7797-E, no. 12)

Who was Frank Merlo, and how long was his relationship with Tennessee Williams? How many people knew that he and the famous playwright were a couple?

Frank Merlo was a Sicilian American from New Jersey who became the life partner of Tennessee Williams in 1948 and remained so pretty much until Merlo’s death—the longest relationship for either of the men. They were still very close when Merlo died of lung cancer, in late 1963. During their life together, Merlo was rarely if ever in the spotlight, even though his partner was such a famous person. Homosexuality was not publicly acceptable at that time, and gay and lesbian couples were not openly acknowledged in the press. Merlo was most often referred to as Williams’s secretary, though occasionally as his friend.

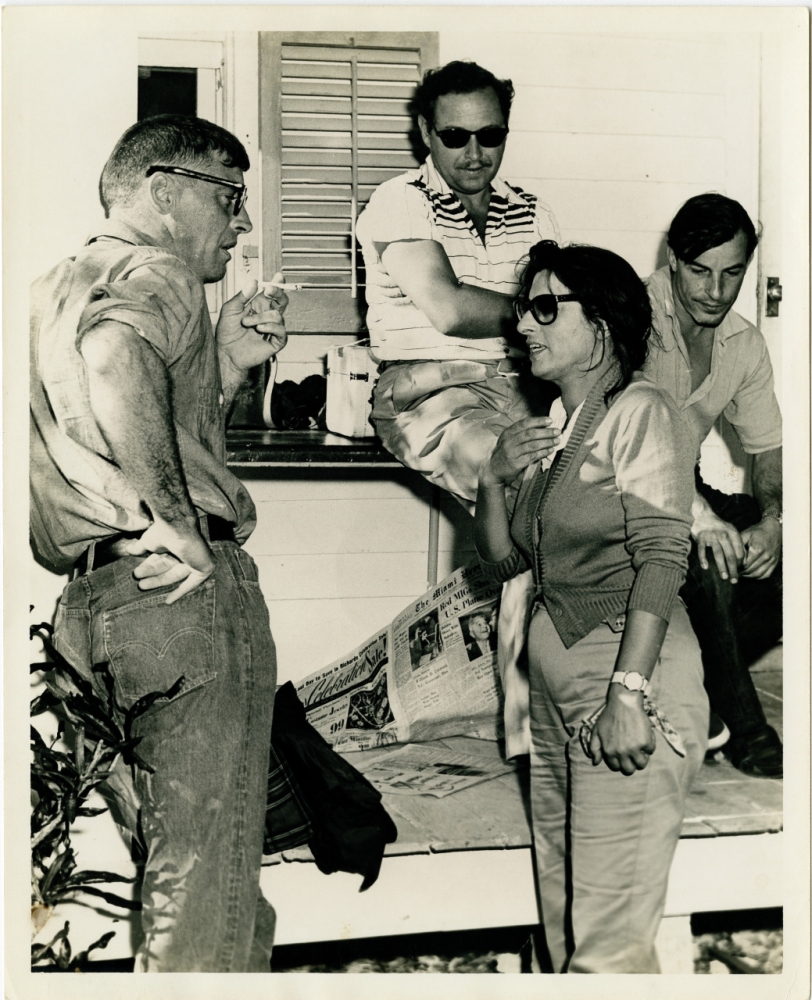

Tennessee Williams (top) and Frank Merlo (far right) with actors Burt Lancaster and Anna Magnani, on location during the filming of The Rose Tattoo in 1955. (THNOC, Fred W. Todd Tennessee Williams Collection, 2004.0277.2.)

Williams is famous for writing plays, such as A Streetcar Named Desire and Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. Is Merlo in any of his plays?

A figure called “a memory of Frank Merlo” appears briefly in the 1981 play Something Cloudy, Something Clear, but a more interesting representation of Merlo is the character of Alvaro, a Sicilian truck driver, in the romantic tragicomedy The Rose Tattoo, written by Williams in the years just after their relationship began. Like all of Williams’s characters inspired by people in his life, Alvaro is not intended to be an exact replica of Merlo on stage: rather, the playwright drew Alvaro with Frank’s playfulness, sense of humor, deep feelings, and athletic physique.

Did Williams write a lot of poetry? Is it any good? Are the poems similar to the plays?

Yes. Yes. Yes and no. Williams decided he was a poet at a young age and felt that way all his life. Shortly before his death he wrote, “I know that it is the poetry that distinguishes [my] writing when it is distinguished, that of the plays and of the stories.” Williams felt that poetry was intrinsic to all his writing, and he was right. The director Elia Kazan, for example, said of Williams’s experimental 1953 play Camino Real, “I’m not sure [it] is as much a play as a poem.” The poems are by nature quite different from the plays in being a distillation and evocation of feelings and ideas, or the expansion of a passing moment into words, rather than a narrative story. They are often more overtly personal and reveal details of his life and thought process.

You have been editing Williams’s writing for New Directions for more than two decades—you know a lot about his life and his work. Did this poem surprise you in any way? What did you find most interesting about it?

This poem did surprise me: Williams puts himself in a real-life scenario—next to the bed where Merlo lies attached to an oxygen tank—and he directly acknowledges Merlo’s death. It was unusual for Williams to be that straightforward about their relationship, particularly in his poetry, until much later. In my introduction, I compare “The Final Day of Your Life” with other, more characteristic poems Williams wrote, which use metaphors and symbolic landscapes to reflect on his relationship with Merlo. Williams is remembered now as having been candid about his personal feelings, someone whose life was mostly an open book, but during his lifetime, that candor—both in his writing and in media interviews—turned out to be trailblazing: it paved the way for the social acceptance yet to come, but at the time it entailed risks and consequences. This poem is a reminder of the pain he felt at the loss of his companion and at his inability to reveal or fully describe the extent of that loss in public.

Tennessee Williams at his typewriter circa 1955, with Frank Merlo seated in the background. (Photograph by Don Pinder; THNOC, Fred W. Todd Tennessee Williams Collection, 2004.0277.2)

Did Merlo have a big effect on Williams’s life? How much does Merlo’s family know about his relationship with Williams? Did they know much at the time?

Merlo had an enormous impact on him that perhaps didn’t become fully evident to Williams until after Merlo died. They were estranged on and off during the time that Merlo was sick with cancer, and after he died, Williams was devastated by the loss and went into a depression and self-destructive spiral that lasted seven years. Merlo was the rock Williams depended upon. “He taught me life,” Williams said in an interview in 1973.

Both of their families knew about their relationship, but, as was common, it was not acknowledged by their families the way it would be today. There was tremendous pressure on same-sex couples back then to remain discreet. Not being acknowledged as a couple, and the logistical and emotional effort involved in outright hiding their attachment, as they often did, took its toll on their relationship.

As it happens, a cousin of Merlo’s, a playwright named Joey Merlo, who lives in New York, has recently done much of the research that has led to a better understanding of Merlo’s background and life. The family is quite proud of them both.

How has Williams’s sexuality shaped scholarship around his work? As more info about his sexuality has come to light, and as homosexuality has become less taboo, have scholars started looking at his work differently?

Well, like so many writers who happen to be gay, Williams considered himself a playwright, not a gay playwright. That said, however, his deeply empathetic perceptions into human nature helped him write characters who exhibit a wide range of human sexuality, much of it outside of gender and societal norms. In fact, Williams broke new ground in the depiction of sexuality on stage and in the movies, particularly when it came to female desire and eroticism, the sexual objectification of men, and all manner of transgressive or taboo sexuality. Same-sex desire in plays such as A Streetcar Named Desire and Cat on a Hot Tin Roof is no longer censored, though it was removed from the original Hollywood film versions. What percentage of the general public knows that the famous 1950s Hollywood film adaptations left out the gay content is hard to say—those films were and remain popular with many people who don’t know there’s anything missing.

At the time that his plays and films first appeared, Williams was often reviewed and marketed as a scandalous or steamy writer, when in fact his characters are much more subtle and understandably human than the advertising implied. Sensational marketing of films has not changed all that much, but the public understanding and acceptance of human sexuality has expanded dramatically in the last seventy years, perhaps in some part due to the impact of Williams’s iconic characters on popular culture.

The 1955 poster for Cat on A Hot Tin Roof (THNOC, Fred W. Todd Tennessee Williams Collection, 2003.0147.4)

Is there anything else readers should know about Williams, Merlo, or this poem?

I continue to be surprised and impressed by Williams’s seemingly limitless imagination and also by his endurance. He wasn’t merely disciplined—as a creative person, he was driven. Critics who desperately wanted him to write plays like A Streetcar Named Desire and The Glass Menagerie again were angry and disappointed with the experimentalism of his later plays. He was frustrated by the criticism, yet he persisted in writing only the kind of work that compelled him.

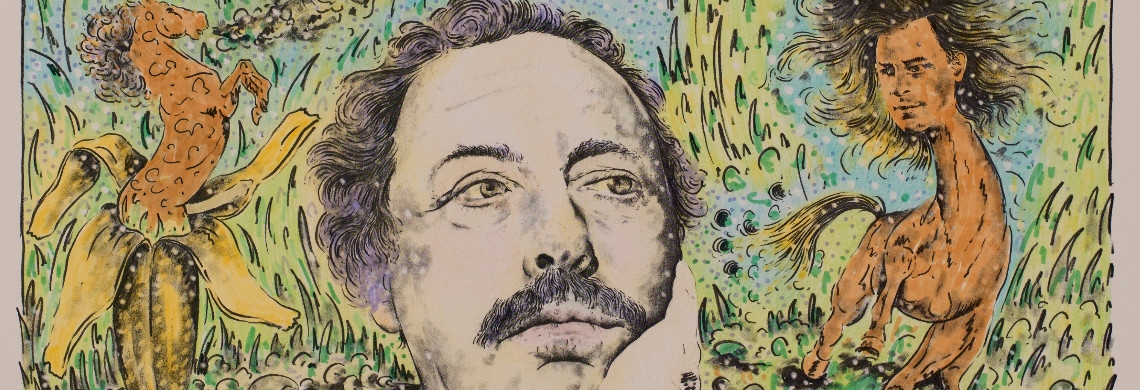

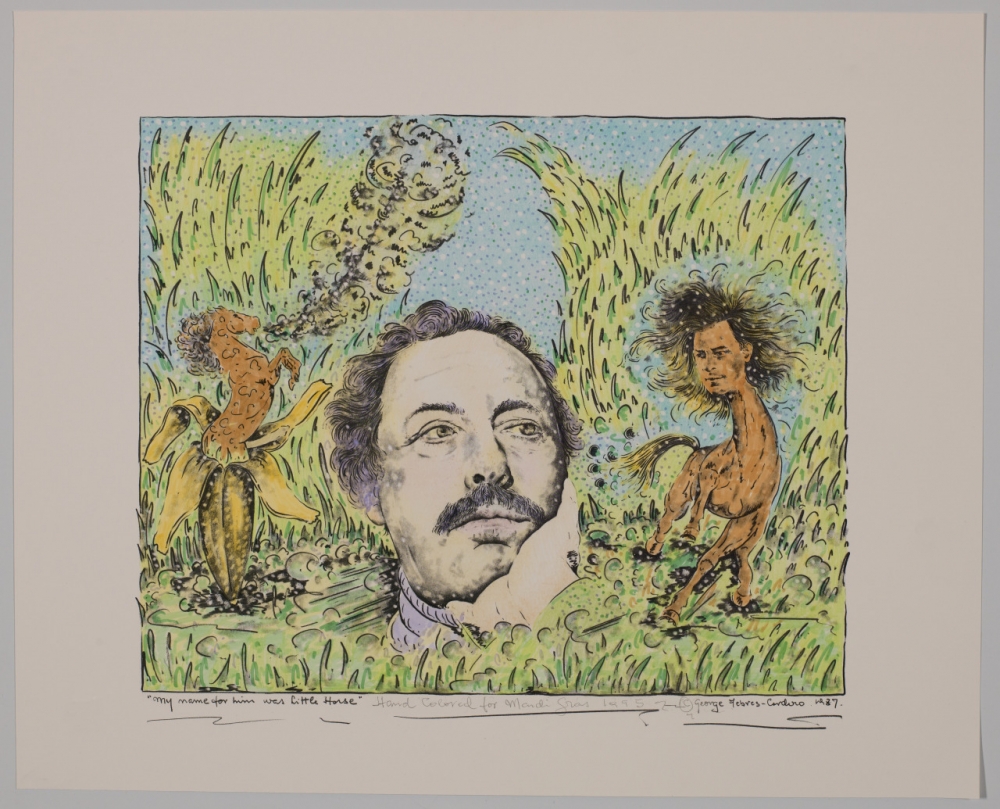

Williams’s personal collection included a drawing by an artist in his circle, George Febres, who gifted the playwright this 1987 portrait of Williams and Merlo, created using photographs of the two men. Febres’s title, “My Name for Him Was Little Horse,” is a line from Williams’s poem “Little Horse,” dedicated to Merlo. (THNOC, 1996.78.1.50.)