As New Orleans reels under the global outbreak of the new coronavirus, lessons from a 100-year-old pandemic have come back with a new urgency.

People around the city and the world are looking back on the fast-evolving terror of the 1918–19 Spanish influenza and the steps that were, or weren’t, taken to stop it. In New Orleans, the disease killed more people than had died in all but the worst yellow fever epidemics.

Why was the outbreak so devastating? Health officials initially downplayed the threat of the virus. People did not heed warnings to avoid mass gatherings and chose to attend parades and rallies for WWI relief. Victims died quickly, sometimes within hours of contracting the disease.

Between September 8, 1918, and March 15, 1919, there were 3,362 influenza-related deaths in New Orleans—nearly one percent of the city's population and about twice the national rate.

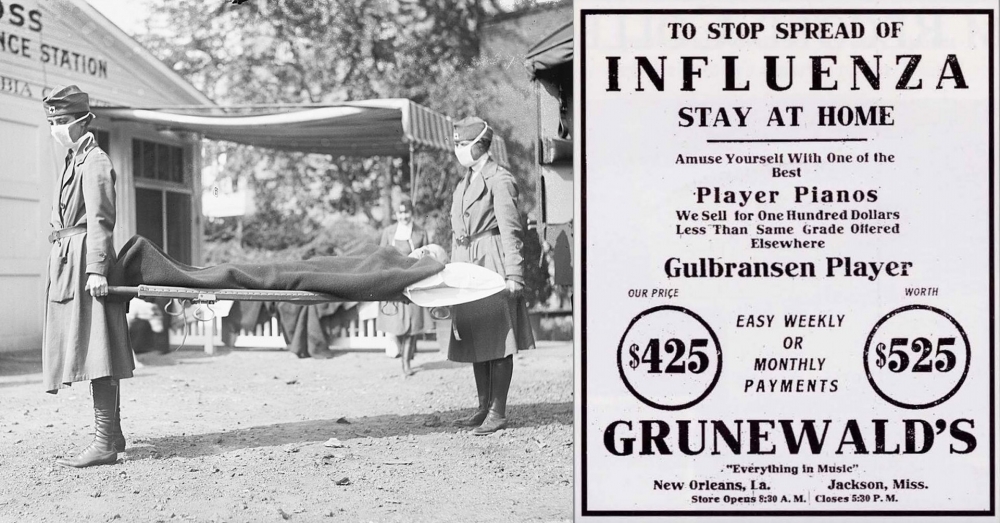

Nurses in Washington, DC, demonstrate how to carry an influenza patient on a stretcher. When the disease struck New Orleans, it killed more people than all but the worst yellow fever outbreaks. (Library of Congress)

"Spanish" is a misnomer: There’s insufficient evidence of a defined origin, but the first identified cases in the US appeared at Fort Funston, Kansas, in the spring of 1918. (According to a recent deep dive by USA Today, Spain stood alone in reacting quickly to the outbreak, which unduly linked the country with the virus in the public imagination.) The initial outbreak was mild, but by summer the influenza was raging in Europe and returned to the United States with a vengeance in late August.

The latter visitation attacked military bases and northeastern cities before spreading westward across the United States like a wave. At first the Spanish flu seemed a long way from New Orleans. The Daily States referred to it as the "sneeze malady" or the "sneeze plague."

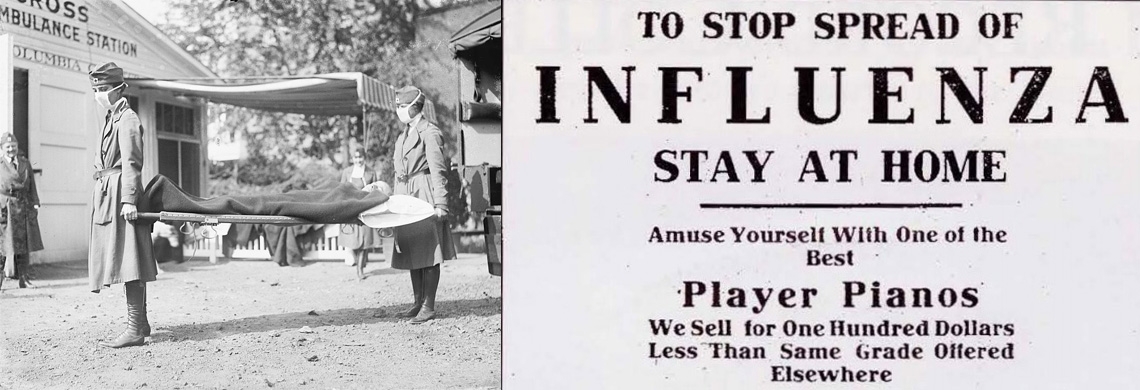

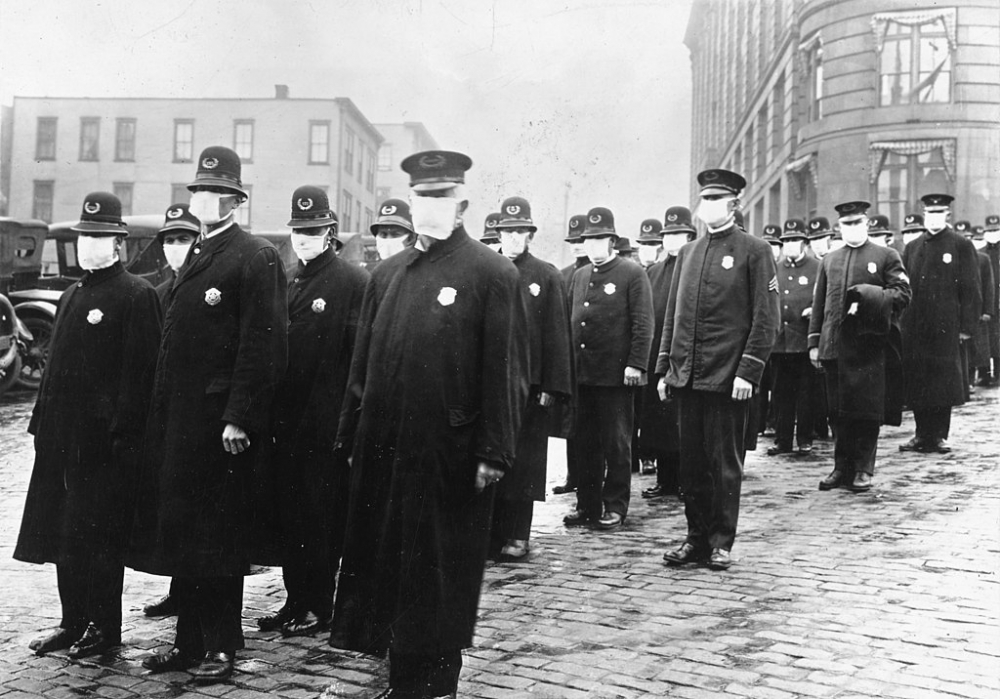

Soldiers in New York are shown wearing masks to slow the spread of the pandemic. The first known cases of the Spanish flu to occur in the US appeared at a Kansas military base in spring 1918, and disease took a heavy toll on soldiers toward the end of WWI. (National Archives)

On October 1, the Times-Picayune carried a statement from Dr. William H. Robin, president of the New Orleans Board of Health: "Influenza does not spread, or become severe in warm, sunny weather, such as prevails during the greater part of the year in New Orleans." Nonetheless, the newspaper warned that the disease could leave a "trail of death."

Virtually nothing was known about the viruses that cause influenza, although Spanish flu was recognized as more virulent than the common grippe—and it was often trailed by secondary pneumonia. Pneumonia was the most common killer in the United States before the use of antibiotics, which were about a decade away from being invented.

With Spanish flu, the onset was rapid, and death could come within hours: Luis A. Caro, Colombian consul general in New Orleans, left his office on a Friday and was found dead in his rooms at the Lafayette Hotel the following Monday.

Seattle police officers don masks to fight the spread of the virus. The New Orleans Board of Health suggested that the city’s warm climate would be inhospitable for the virus, but the disease gripped the city beginning in September 1918. (Wikimedia Commons)

The flu was spreading around Boston's Commonwealth Pier when the oil tanker Harold Walker set sail for New Orleans on September 5. On board were 15 sick crew members, three of whom would die. One of the dead, who was from New Orleans, was reported by the Times-Picayune to be the first New Orleanian to die of the new influenza.

It’s possible that the Harold Walker brought the Spanish flu to the city. Sometime between September 21 and 28 the "sneeze malady" silently began its onslaught. Louisiana's military bases, crowded with World War I troops, fell victim first. On September 28 Camp Beauregard near Alexandria was under rigid quarantine, with quarantine restrictions to follow at Camp Martin on the Tulane University campus—where one of the first outbreaks in New Orleans occurred—and at the Algiers Naval Station.

Soldiers crammed into barracks, like this one at Camp Martin in New Orleans, were prone to catch the disease. (THNOC, 1987.62.27)

By October 5 the epidemic was spreading rapidly throughout the South, and by mid-October the illness raged in New Orleans.

Because overcrowding was deemed the major cause of contagion, health officials proposed every manner of keeping people separated. Doctors and media warned people to stay home from the planned parade on Canal Street for the Fourth Liberty Loan on September 28—an attempt at what we would call social distancing—even though Americans were generally encouraged to attend such war-relief efforts. People did not heed these warnings and crowded Canal Street and the parade route. On October 5, a war rally in Lafayette Square attracted 50,000 people, and a few days later thousands packed the Orpheum-St Charles Theater to buy Liberty bonds.

Within days the city was awash in influenza cases.

Nurses march in the Fourth Liberty Loan parade on September 28, 1918. The parade drew huge crowds on Canal Street, even though health officials had urged people not to congregate. (THNOC, 1993.51.27)

By the second week of October, most war rallies were canceled throughout New Orleans, as the city and state boards of health began to impose stringent safeguards against crowding. Schools, movie houses, theaters, dance halls, and churches were closed, while public meetings, concerts, sports events, street gatherings, public weddings, and public funerals were prohibited. Influenza victims had to be buried quickly without church services (and in the presence of a health official), rigid anti-expectoration laws were enforced, and stores agreed to stop advertising special sales.

Saloons, pool halls, ice cream parlors, and restaurants were allowed to remain open but faced closure if they became overcrowded or neglected to follow strict sanitary regulations. Streetcar crowding was an ongoing issue. Union regulations prohibited drivers from operating extra trips, but the issue was moot as 175 drivers were out sick. Most families had at least one sick member. Several temporary influenza hospitals opened to look after the seriously ill.

The epidemic took an economic toll as well. Merchants reported decreased sales, businesses operated with reduced staffs, and restaurants served fewer customers—similar to but less severe than the disruptions we’re experiencing as part of the current crisis. Tulane University called off all classes; Newcomb College was closed. The new Cumberland Telephone Company was unable to open its lines on schedule because so many operators were out sick.

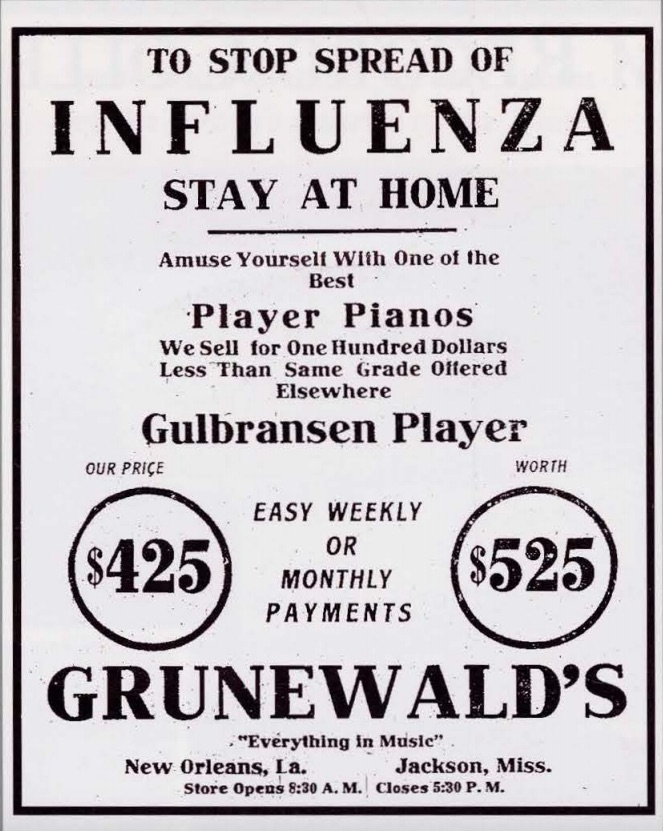

An advertisement in the October 17 Times-Picayune admonishes readers to stay home. (THNOC, 82-099-L)

As with much of the coronavirus coverage today, newspapers and officials aimed to strike a balance between addressing public concern and discouraging panic. Newspaper advertisements told readers how to avoid the flu and its complications but added, "Don't Get Scared," and "Don't Be Alarmed—Be Careful!" Dr. Oscar Dowling, head of the state board of health, however, feared that New Orleanians were still congregating too much. If crowding did not cease, Dr. Dowling warned, "there is the greatest sort of danger that we will find ourselves in a most appalling situation."

With so little knowledge of the flu virus, doctors could only offer advice, such as to eat foods containing milk—which caused a milk shortage. Nurses were essential, but their services were stretched to the limit.

By October 9, only 24 of the city's 646 doctors had made reports to the board of health. At this time, according to one estimate, there were 58,000 cases, although only 8,000 had been reported. The numbers began climbing soon, however, as doctors learned they could be prosecuted if cases went unreported. By October 16, the number of reported cases rose to more than 4,000 for that one day—and new cases per day exceeded 2,000 through October 24. Not until October 29 did the daily influenza count fall below 1,000.

As the new cases subsided, pneumonia deaths related to influenza increased dramatically. On one day alone 147 people died, and in a two-week period, there were 1,306 deaths reported.

After a surge of deaths, the epidemic started to subside in November 1918. Activities like All Saints Day were allowed to take place, and people—including the men and women shown here—flowed into the streets to celebrate the signing of the Armistice to end fighting in WWI. (THNOC, 1974.25.21.25)

Following its own course, the epidemic began subsiding rapidly in November. Activities on All Saints Day were allowed to take place, and church services resumed on November 3. Schools and other businesses opened soon afterward. Even with huge crowds pouring into the streets on November 11 for Armistice Day, celebrating the end of World War I, there was no immediate recurrence of the epidemic.

In January, the Spanish flu returned to take 763 more lives. But with the arrival of spring, the misnamed flu was gone, and New Orleanians could look forward to happier—and healthier—times.

The Historic New Orleans Collection is documenting the public response to the COVID-19 pandemic in New Orleans. Learn how you can contribute to the historical record in our latest First Draft story.