Editor’s note: This story is adapted from Enrique Alférez: Sculptor, by Katie Bowler Young, now available from The Historic New Orleans Collection. Learn more about the book, and purchase a copy, here.

Enrique Alférez’s lasting imprint is seen throughout New Orleans, among figurative sculptures, monuments, fountains, and architectural details in prominent locations from the Central Business District to the shore of Lake Pontchartrain and beyond. From 1929 until his death in 1999, Alférez frequently had a home in the city, where a majority of his artwork is on public view.

Born in Zacatecas, Mexico, Alférez first came to the United States as a youth and spent much of his life here. He trained at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and spent time in El Paso, New York City, and in cities throughout Mexico, including Morelia, over the course of three decades. But in New Orleans, Alférez left his largest body of work, helping shape the essence of one of the most interesting cities in the United States.

Below are 11 locations in New Orleans where Alférez’s work is on display—and the fascinating, and sometimes controversial, stories behind some of his most iconic works.

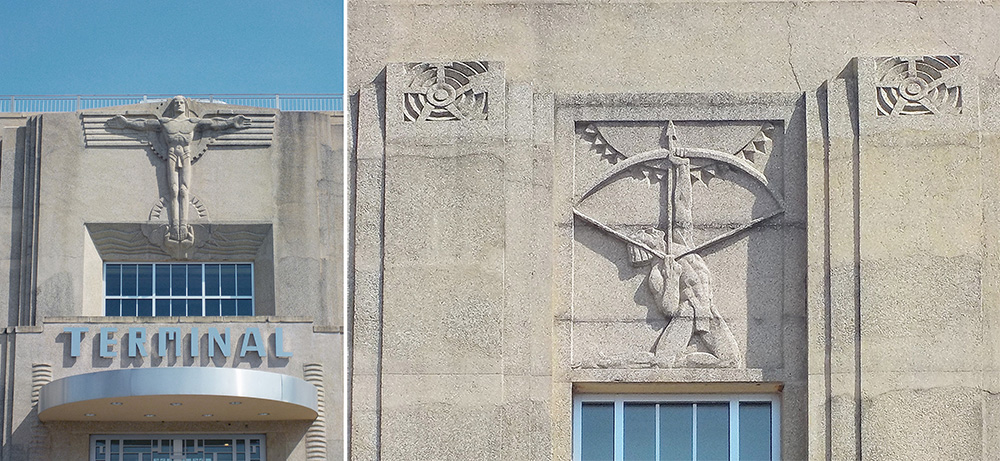

1. New Orleans Lakefront Airport facade

Photographs by Alison Cody.

Alférez began working at Shushan Airport (now known as the New Orleans Lakefront Airport) in late 1932 or early 1933. In an interview conducted in 1975, Alférez said he created one of the three panels on the front facade of the building—the Indian shooting an arrow into the sun—and the large central figure above the portico. The other two panels were completed by William Proctor and John Lachin. Alférez worked on the plaster reliefs at his studio on Saint Ann Street. In the first panel, Alférez’s mythological figure aims his arrow toward the sun, symbolic of the dream to penetrate the skies.

At the center of the panels, high above the entrance and second-floor windows, is the most dramatic piece Alférez made for the exterior, a cast-stone sculpture with mythological influence: Man as a Flying Machine. It dominates the top of the building, and the figure seems to be soaring, his feet resting in a set of hands that are nestled in clouds.

2. Fountain of the Four Winds, New Orleans Lakefront Airport

Photograph by Donn Young.

One of Alférez’s defining works, the Fountain of the Four Winds, was installed about a hundred yards from the entrance to the Lakefront Airport in 1938. The main element of the fountain, four kneeling figures facing outward, is centered in an elliptical basin. The allegorical nude figures, three female and one male, represent the four mythological winds, each placed at its appropriate compass point. The fountain has been restored on multiple occasions, including by Alférez himself, but needs further restoration today.

At the time it was built, the Four Winds stoked controversy. “The [project] seemed to be going well until some puritanical SOB insisted that I was contaminating the morals of our WPA men because one of the figures was a nude male,” Alférez told art critic and dealer Luba Glade. According to Alférez, the offended WPA official threatened to destroy the fountain with a sledgehammer.

Alférez reached out to Lyle Saxon, a respected New Orleans journalist and editor of the WPA’s New Orleans City Guide, hoping he would intervene. Saxon appealed to a higher authority: he wrote two letters, one to First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who was in California at the time, and the other to President Franklin D. Roosevelt in Washington, DC, and included photos of the North Wind. Mrs. Roosevelt, an ardent supporter of the arts, recommended that the fountain should be kept as it was. Alférez took the letters to WPA administrators and to other leaders, and with the evidence of support, the controversy was settled. The fountain is often considered Alférez’s finest public work.

3. Louisiana at Work and Play, Charity Hospital

Photograph by Donn Young.

From 1936 to 1938, Alférez created a number of works for the new Charity Hospital, including an approximately 17-by-17-foot aluminum grille called Louisiana at Work and Play above the main entrance of the 20-story hospital. When it was installed in November 1938, art critic W. M. Darling—struck by the grille’s size relative to the massive building—described it as “a work in tiny detail.”

The sculpture was designed to reflect Louisiana culture as well as the people whom the hospital served. It includes a large nude figure at the center. One element, a flying duck, got Alférez in trouble because of its symbolic connection to Louisiana politics. The feature was a reference to deductions, or “deducts,” police and state employees were required to pay to Governor Huey Long’s campaign fund, in which they “donated” a portion of their income on payday. Richard W. Leche, who became governor in 1936, continued taking the payments, which had become known colloquially as “de ducks.” “De ducks are flying” was frequently said when the funds were collected. When the hospital opened in 1939, it was mired in irregularities that had begun during construction.

Alférez couldn’t resist referencing Long and Leche’s unethical “deducts” practice with his inclusion of the duck in the grille design. When the finished aluminum grille was delivered, someone noticed Alférez’s barely hidden message, and word began to spread. Alférez was told to remove the duck, a nearly impossible task at that point. Years later, Alférez would recall that a man was sent to the hospital with a hacksaw to remove the duck from the grille, but a Times-Picayune journalist intervened by telling the man that it would be a federal crime to damage the piece since the hospital had been built with federal funds. The duck remains on the facade of Charity Hospital today.

4. City Park bridges

Photograph by Alison Cody.

By early 1936, Alférez had begun working on bridges for City Park under the auspices of the Works Progress Administration’s revamp of the park. The detail on the bridges was considered “unusual and striking” at the time. Alférez’s work on the lagoon bridges appears in three areas: on the facades, most easily viewed from a boat; on the wing walls; and on the entry points to bridges.

On one bridge in the northern part of the park, Alférez included a series of male figures as tributes to the labor and expertise of those who worked on the park’s development. Each figure uses a tool—shovel, wheelbarrow, or surveying equipment, to name a few—and Alférez included African American figures. At the time, white society banned African Americans from the park, a restriction that remained in effect until 1958. Alférez said that he “got in trouble” for including the figures and that he received letters from irate residents who thought that African Americans should not be portrayed.

But Alférez observed that there were African Americans working at the park and said they were talented craftsmen. “They had pride in the work,” said Alférez. “I know because I was with them.” With these words, he wasn’t just referring to his work alongside African Americans; he was also commenting on how he was subject to similar social penalties. In projects like this, with the access that his expertise as a sculptor gave him, he rebelled against racist social constructs and created artwork that reflected the public more broadly. Alférez’s making monuments to the people who built City Park was a radical act at the time.

5. New Orleans Botanical Garden, City Park

Photograph by Ashley Merlin.

The densest representation of Alférez’s work is in City Park’s New Orleans Botanical Garden, known as the Rose Garden when he first began his work at the park in the 1930s. There, he created fountains and figures as well as details that set the tone for the garden: cast-stone benches that feature frogs, crickets, foxes, and other creatures; cubist-influenced drinking fountains; art deco light standards; and poles embellished with figures of a satyr and a nymph.

In the 1980s Alférez returned to the garden to refurbish some of his older works that had fallen into disrepair, ahead of the 1984 Louisiana World Exposition, and created important work for the garden in the following years. The last major sculpture that Alférez created for the Botanical Garden is also among his distinctive works. The Flute Player was commissioned in 1994 and went on view in 1996. The larger-than-life figure stands in a small fountain pond beside a live oak, her dark body occasionally turning green at the calves from a slight spray of water.

In 2015 the Botanical Garden opened the 8,000-square-foot Helis Foundation Enrique Alférez Sculpture Garden to celebrate Alférez’s influence in the park. Figures continue to arrive as New Orleans residents become inspired to share pieces that had once been in their homes or gardens.

6. Molly Marine, Elk Place

Photograph by Ashley Merlin.

Molly Marine, the first monument to women in the military in the United States, was dedicated on the US Marine Corps birthday—November 10—in 1943, following the 1942 establishment of the Marine Corps Women’s Reserve.

Charles Gresham, a technical sergeant and recruiter for the Marines in New Orleans, was interested in having a monument made to recognize women in service. He encouraged Alférez to make the figure. Alférez created the 12 1/2-foot Molly by working with five models, including his neighbor Judy Musgrove, and four female Marines. Molly was cast with donated marble chips and granite blended into concrete, eliminating the need for wartime-restricted metals.

By the early 1960s, the statue was in need of cleaning and repair. In 1966, the monument received a new marble pedestal and a bronze wash over the cast cement; by 1988, the bronze wash had begun to chip, so the statue was sandblasted, cleaned, and given a new spray coating of bronze. In 1999, plans were made to reproduce and restore Molly again. Alférez made a mold of the statue on-site at Elk Place so that copies could be cast in bronze. Two replicas were installed at the Marine Corps Recruit Depot at Parris Island, South Carolina, in 1999; and at the Marine Corps Base at Quantico, Virginia, in 2000.

7. David, 909 Poydras Street

Left: Benito Juárez; Photograph by Donn Young. Right: David; Photograph by Eli A. Haddow

Left: Benito Juárez; Photograph by Donn Young. Right: David; Photograph by Eli A. Haddow

Alférez rarely created works that celebrated machismo or military prowess. In the 1980s, however, he created two strikingly similar tributes to masculine strength, both in cast bronze. Benito Juárez, a portrait of the president of Mexico between 1861 and 1872, was unveiled in Morelia, Mexico, in 1984, and David, a portrait of the young biblical shepherd, was unveiled in New Orleans in 1988. It still stands, opposite his sculpture Lute Player (inset), at 909 Poydras Street.

Alférez rarely created works that celebrated machismo or military prowess. In the 1980s, however, he created two strikingly similar tributes to masculine strength, both in cast bronze. Benito Juárez, a portrait of the president of Mexico between 1861 and 1872, was unveiled in Morelia, Mexico, in 1984, and David, a portrait of the young biblical shepherd, was unveiled in New Orleans in 1988. It still stands, opposite his sculpture Lute Player (inset), at 909 Poydras Street.

Alférez saw a connection between the biblical David and Juárez that he began drawing at least as early as 1980, seeing Juárez—who had shepherded as a youth—as a shepherd of his country as well. Alférez gave nuanced attention to the planes, styles of their clothing, and physical gestures.

Both figures stand firmly, with their legs slightly apart, although there is a subtle difference in their torsos and shoulders. The plane of David’s shoulders is at a more accentuated angle, invoking a sense of defiance and courage, with the figure’s chin thrust upward to see his giant foe; the statue of Juárez is more squared off to face a peer at eye level. There are differences in their attire as well, designed to match their time and place, with Benito Juárez in a serape and David in a cloak, or cape.

8. The Family, New Orleans Botanical Garden (originally 501 North Rampart Street)

Photograph by Keely Merritt.

Architectural firm Curtis and Davis hired Alférez to produce a sculpture that was installed in 1951 on an otherwise empty white marble exterior wall of a municipal court and jail at 501 North Rampart Street, between Toulouse and St. Louis Streets, on the edge of the French Quarter.

The firm requested a work that focused on the family, and Alférez chose as his subject a mother and father with an infant between them. The Family was cast in concrete and finished in zinc and lead. Alférez told New Orleans States-Item journalist Lanny Thomas that he thought the piece was “symbolic of family unity and strength.” It was suspended about a foot from the marble wall by iron rods that allowed the piece to cast shadows on the large and windowless white facade as sunlight changed throughout the day.

The Family was unveiled in a modest dedication ceremony with Mayor deLesseps Story “Chep” Morrison in attendance. Within hours, Father Joseph P. Laux from the nearby Our Lady of Guadalupe Catholic Church and International Shrine of Saint Jude contacted Morrison’s office to object to the nudity of the figures. New Orleans residents began sending letters to the editor, offering their perspective in the court of public opinion. Only about 10 percent of these letters objected to the sculpture. Nonetheless, controversy grew, and publicity of the incident extended around the country and beyond, appearing in newspapers as far away as Canada.

After only three days on display, the sculpture was covered with burlap, moved to a city warehouse, then auctioned off in Lafayette Square. It is now on view in the New Orleans Botanical Garden.

9. Symbols of Communication, New Orleans Museum of Art (originally displayed in the Times-Picayune building)

Photographs by Kyle Encar Photography; courtesy of the New Orleans Museum of Art

Alférez’s Symbols of Communication, a series of bas-relief panels he executed for the Times-Picayune building in late 1967 through early 1968, features a blending of cultures, through the representation of languages. Riding up or down the building’s escalators, a traveler was just a few feet from the walls with Alférez’s panels.

Alférez created patterns on 14 massive plaster panels, some 37 by 8 feet and others 22 by 6 feet. The installation includes letters from Roman and Greek alphabets as well as hieroglyphics from ancient Egypt; Chinese, Japanese, and Arabic characters; and the dots and dashes of Morse code and Braille, to name just a few. The letters and characters are nested together aesthetically, not to create a decipherable message, but to bring languages and cultures together. It’s also possible to find at least one embedded message, a signature reminding the viewer who created the panels. Heading from the first floor by escalator, a viewer could see the name “Enrique” when approaching the second floor.

In 2018, Symbols of Communication was disassembled and placed in storage in advance of the demolition of the building, which occurred in 2019. Since then, the panels were acquired by the New Orleans Museum of Art, where a selection of the panels is now on view.

10. Sophie B. Wright, Sophie B. Wright Place

Photograph by Ashley Merlin.

A monument to Sophie Bell Wright, seen in the eponymous park at the intersection of Magazine and Saint Andrew Streets, is among Alférez’s few statues of public figures. Wright’s (1866–1912) influence as an educator, philanthropist, community advocate, and prison reformer had far-reaching and long-lasting effects. Wright’s work in education particularly resonated with Alférez, who thought education was “the most important human activity”—and the monument carried great meaning for him. Wright was also a member of the Daughters of the Confederacy, a group that furthered the “Lost Cause” narrative that Southern states fought for a just and honorable cause, rather than the preservation of slavery, in the Civil War.

The work was commissioned by the Sophie Wright Monument Committee, which formed in 1986 and raised private donations to fund the project. Alférez modeled the seven-foot statue in plaster in late 1986 to early 1987, and it was cast in bronze. The figure holds a book, symbolizing Wright’s career as an educator, and she is shown in a seated position, a subtle illustration of a disability caused by a childhood accident. The monument was dedicated in 1988. Because of Wright’s ties to the Daughters of the Confederacy, the statue and adjacent street are part of a citywide conversation over whether to remove and rename places named after figures with ties to white supremacist groups.

11. Popp Fountain, City Park

Photographs by Eli A. Haddow.

In 1937 Alférez finished Popp Fountain, one of City Park’s major landmarks, with a pool 60 feet in diameter, surrounded by 26 Corinthian columns, a terrace, and a trellis that, in its earliest days, was covered in wisteria. In 1928, the park received donations totaling $40,000 from Rebecca Grant Popp and her sister Isabel Grant. The fountain took more time to complete than anticipated: it wasn’t finished until 1937.

Alférez designed the central cast-concrete feature of the fountain: dolphins riding waves that rose from a low pedestal. He designed the water to spray 30 feet into the air, in proportion with the pool’s 60-foot diameter, and used the motion of light and water to create visual effects.

In Popp Fountain’s earliest years, lights were submerged beneath the water, but they were eventually replaced with overhead lights. The fountain continued to deteriorate over the following decades, with damage caused by hurricanes and vandalism. A 1947 hurricane damaged 24 of the 26 columns at the fountain. By 1975, the cast-concrete dolphins had been smashed down to the reinforcement rods, and sections of the balustrade had been stolen. The grounds became overgrown and untended. A major restoration effort began in 1993, resulting in the dolphins being recast in bronze, based most likely on Alférez’s memory of the originals. Today, the fountain is among the most beloved sites in the park, a frequent venue for weddings and celebrations.