On Monday, November 14, 1960, four six-year-old girls in New Orleans, accompanied by her mother and two US Marshals each, became pioneers in the national civil rights movement.

Ruby Bridges, Gail Etiénne, Tessie Prevost, and Leona Tate—collectively known as “the New Orleans Four”—were the first Black elementary students to attend previously all-white public schools in the Deep South. Bridges integrated the William Frantz School in her neighborhood of the Upper 9th Ward, while Etiénne, Prevost, and Tate integrated their neighborhood school, McDonogh 19, in the Lower 9th Ward.

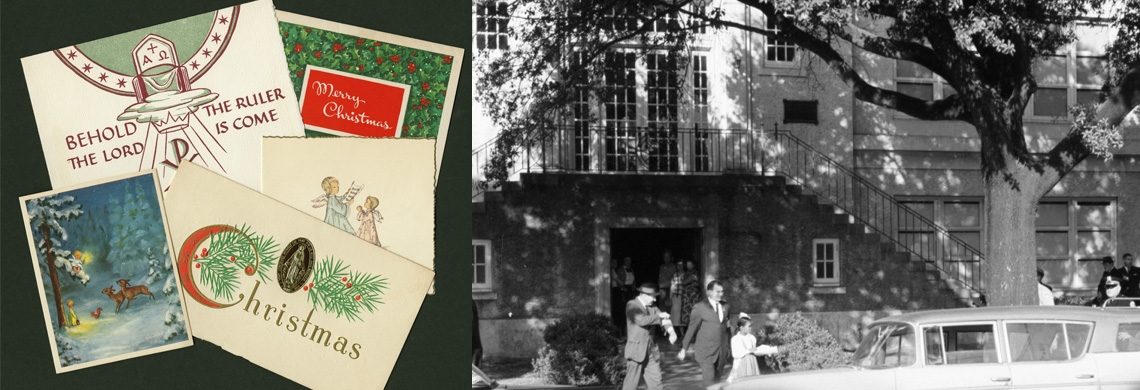

Tessie Prevost is escorted by US Marshals outside of McDonogh 19 Elementary School in November 1960. (The Jules Cahn Collection at THNOC, 1996.123.1.107)

“I don’t really think our families knew that it was going to go nationwide,” said Leona Tate in a recent virtual field trip hosted by The Historic New Orleans Collection’s education department. “I think they just thought it was a local thing. I knew I was going to a new school, a different school, but I really didn’t understand why...it was years down the line before I had really realized what I had done.”

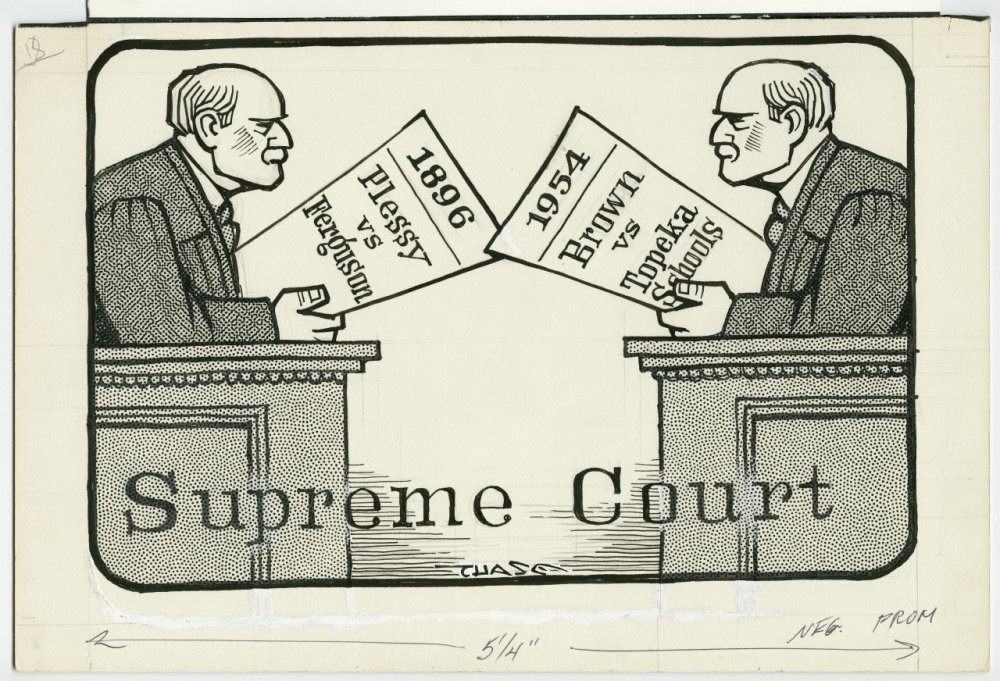

This 1977 political cartoon by John Churchill Chase recalls the 1896 case Plessy v. Ferguson (163 U.S. 537), which allowed states to segregate by race, and the 1954 case Brown v. Board of Education (347 U.S. 483), which reversed the Plessy v. Ferguson ruling. (THNOC, Gift of Mr. John Churchill Chase and Mr. John W. Wilds, 1979.167.18)

This 1977 political cartoon by John Churchill Chase recalls the 1896 case Plessy v. Ferguson (163 U.S. 537), which allowed states to segregate by race, and the 1954 case Brown v. Board of Education (347 U.S. 483), which reversed the Plessy v. Ferguson ruling. (THNOC, Gift of Mr. John Churchill Chase and Mr. John W. Wilds, 1979.167.18)

The long road to desegregation

Six years before the New Orleans Four entered their respective schools, the US Supreme Court issued a monumental, and unanimous, ruling that changed education across the country. The 1954 case of Brown v. the Board of Education of Topeka determined that segregating students by race was a violation of the 14th Amendment, which afforded equal civil and legal rights to all citizens.

The 14th Amendment passed in 1868, shortly after the Civil War, and was intended, in part, to ensure liberties to formerly enslaved laborers. But those rights were not made available to all citizens equally, and people of color frequently faced obstacles voting, owning property, securing legal representation, and accessing education.

The Supreme Court ruling of Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896 presented another setback in the quest for racial equality.

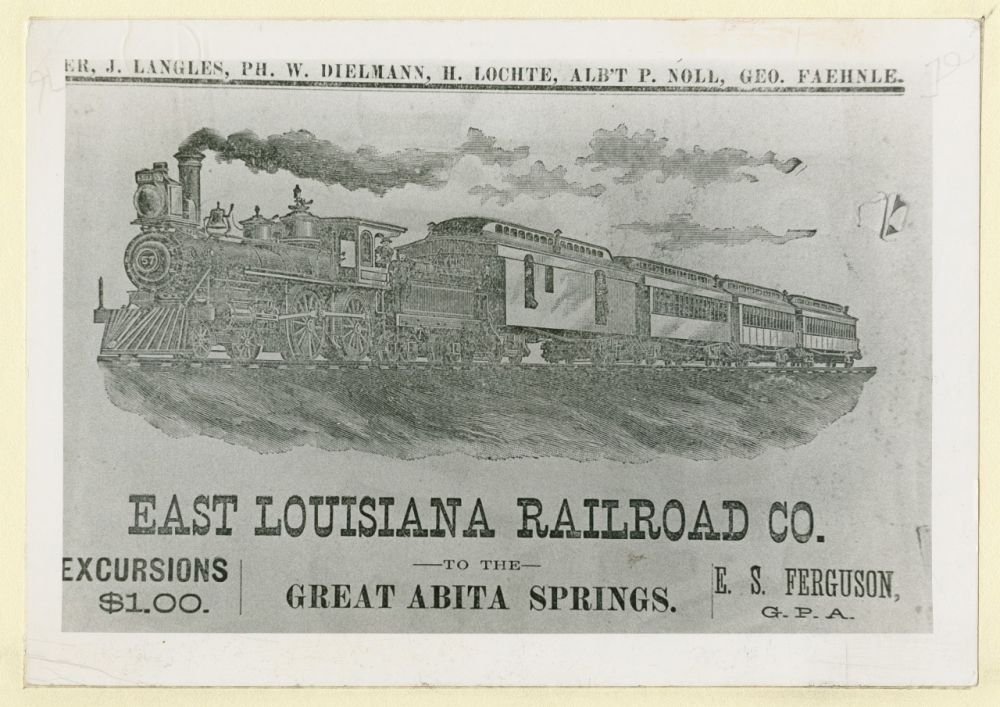

In June 1892, Homer Plessy, a mixed-race New Orleans man, purchased a ticket on the East Louisiana Railroad and sat in a whites-only car. He was ejected from the train and arrested for violating the state’s segregation orders. Plessy’s case reached the Supreme Court in 1896 and legalized the “separate but equal” doctrine. (THNOC, 1974.25.37.57)

In June 1892, Homer Plessy, a mixed-race New Orleans man, purchased a ticket on the East Louisiana Railroad and sat in a whites-only car. He was ejected from the train and arrested for violating the state’s segregation orders. Plessy’s case reached the Supreme Court in 1896 and legalized the “separate but equal” doctrine. (THNOC, 1974.25.37.57)

The case, which originated in New Orleans, challenged the decision to separate Black and white people on public transportation, specifically a rail car. But in his majority ruling, Justice Henry B. Brown concluded the decision to separate “the two races” should be left to the states, and segregation did not “necessarily imply the inferiority of either race to the other.” Justice Brown went on to add, “The most common instance of this is connected with the establishment of separate schools for white and colored children, which has been held to be a valid exercise of the legislative power even by courts of States where the political rights of the colored race have been longest and most earnestly enforced.”

The standard for accommodations that resulted from the Plessy v. Ferguson ruling would commonly be referred to as “separate but equal,” and for nearly 60 years schools, hospitals, businesses, public transportation, and more could legally choose to segregate, provided a “comparable” facility for people of color was available. While local governments enforced the separation of the races, they did not enforce equality among the separate resources.

By the 1950s the disparity in schools for Black children compared to those for white children was plainly apparent. And, with the Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in Brown v. the Board of Education of Topeka, “separate but equal” accommodations became illegal. The federal court declared segregation unconstitutional and, in a decision the following year, ordered states to integrate their public schools “with all deliberate speed.” Yet the court’s ruling did not provide a specific timeline or a clear path to school integration.

These women can be seen protesting the desegregation of the William Franz School in the Upper 9th Ward of New Orleans. (THNOC, 1974.25.25.113)

These women can be seen protesting the desegregation of the William Franz School in the Upper 9th Ward of New Orleans. (THNOC, 1974.25.25.113)

Many white parents in Louisiana vehemently protested the idea, and school boards and politicians sought to block desegregation in the state. Frustrated by the stalemate, Federal Judge J. Skelly Wright presented a plan for integration to the Orleans Parish School Board.

Schools also had a choice. They could opt to close if they refused to integrate.

With the political debate raging, all paths toward integration were blocked. So, in May 1960, Justice Wright ordered OPSB to integrate its schools by the start of the 1960–61 school year.

“While schools, parents, and politicians argued about how to proceed—whether to integrate schools or close them—the OPSB received approval to delay the first day of public school integration to November 14, 1960,” said Eric Seiferth, THNOC historian and curator.

“By three o’clock we were the only students”

In a recent virtual field trip with THNOC, Leona Tate reflected on that day:

“When I woke up that morning my house was filled with family and friends there to support my mother. I thought it was like a holiday … everybody seemed to be in a happy mood, but all of a sudden a black car pulled up in front my door. And the US Marshals had arrived to bring us to the school. I can remember my household getting real quiet. I can remember that silence. So, I knew something was about to happen then.

Gail Etiénne is pictured in the back of a US Marshal's vehicle as she is tramsported to the McDonogh 19 School on November 14, 1960. (Image courtesy of the Leona Tate Foundation for Change)

Gail Etiénne is pictured in the back of a US Marshal's vehicle as she is tramsported to the McDonogh 19 School on November 14, 1960. (Image courtesy of the Leona Tate Foundation for Change)

“My mother and I went to the door, and she told me, ‘When you get in the car, you sit to the back of the seat and do not put your face to the window.’ And I tell all children today that obedience played a big, big part of what we had to do. We had to, we had to listen, and I did. And we left with the marshals.”

Tate continued her reflection, commenting on the excitement of being driven to a school that was in her neighborhood, and explaining the confusion she felt upon seeing the large crowds of people outside McDonogh 19 on St. Claude Avenue:

“When my car … turned that corner, all I could see was mobs of people and police on horseback. So being six years old from New Orleans … the only thing we could relate it to was that a parade was coming. And I kinda remember asking my mama why I had to go to school and everyone else got to watch the parade, and she said, ‘No, that’s not the case.’”

A group of white onlookers gathers outside of William Frantz Elementary School, where Ruby Bridges was the first Black student. (THNOC, 1974.25.25.164)

The angry crowds outside yelled insults and spat on the young girls, their mothers, and the supporters who came to champion them. Once inside the school, the parents headed to the school office, and the girls waited in the hallway.

“We were asked to take a seat on a bench outside of the office, and we must’ve sat on the bench half that day waiting to be placed in a classroom. … Tessie, Gail, and I played hopscotch on the tiles on the floor because we had been out there for a long time, but that’s mainly how the morning was. And then once we got placed in a classroom it was white flight. Parents pulled their students out. By three o’clock we were the only three students in the entire building for a year and a half.”

“Now you got to remember we went there in November … and school was in session. Each classroom had the full capacity of students, and the whole school was filled with students. … I remember going into the classroom … and I remember trying to speak to a little white girl, and it was like I was invisible. She didn’t even respond. But then their parents just started coming and just started pulling them out of the classroom. It was like, like a whirlwind. … They weren’t going to the office and checking them out, they were just coming to get their children. And, that’s how it was. By the end of the day, they were all gone. We couldn’t understand that, but it happened.”

McDonogh 19 school is shown here in the 1930s. (THNOC, 1979.325.1866)

Tate described a first-grade environment vastly different than most and explained how the consequences of attending McDonogh 19 lasted far beyond that first day:

“Once we got home we were so confined. … Everywhere we went we were either chaperoned by a police car that was watching our household or the marshals. The marshals would bring us to school and bring us home, but the New Orleans Police Department guarded our houses. ... If anybody was to come [to the house], if I had a friend or a cousin or somebody to come play, we had to know that they were already coming, and it would be inside—it would never be outside.

“School was the same way. We never played outside; we had to bring our food and beverages. We couldn’t look out of the windows. The windows were papered up. Our play area was under a stairwell inside the school building. We had a very good first grade teacher that was more motherly than anything so she was right there with us. But as far as our childhood life, it was quite different after that. It was quite different.”

Hope for the Holidays

After weeks of turmoil, change, and isolation, the New Orleans Four received unexpected messages of encouragement and hope as the holidays approached. Strangers from across the country—including school children and even former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt—sent the girls hundreds of Christmas cards. In 1990 Tate entrusted her collection of cards to THNOC.

In 1990, Tate entrusted her collection of cards to THNOC, a selection from which is shown here.

“This collection includes cards from California, Colorado, Massachusetts, New York, and more,” said Seiferth. “It’s truly inspiring and heartwarming to see this compassion from so many people around the country.”

Many of the cards were sent to the local offices of the NAACP and the Southern Conference Educational Fund, two organizations that worked with the Bridges, Etiénne, Prevost, and Tate families in advance of desegregation and prepared them for the realities they would face. Upon receiving the letters, the organizations delivered them to each of the girls’ families.

“For me to get as many cards as I got was exciting,” said Tate in a recent interview with WGNO. “It was a while before I was able to read them and really understand what I was reading, but my aunt saved them for me, and I had a chance to go through them.”

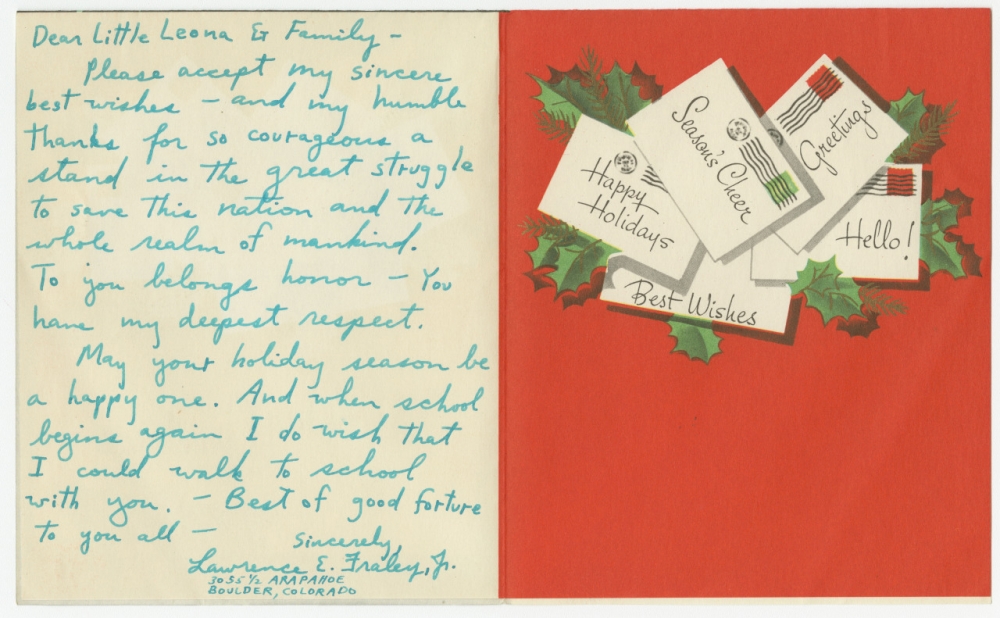

In one holiday greeting to Tate, Delores Black of mother of two sons, then ages 11 and 13, praised Leona for the stand she and her peers and their families were taking and reminded the girls of the significance of the moment. “Your courageous actions will also be the deciding point as to whether my boys will continue to go to integrated schools or not. I feel sure that if the State of Louisiana were to win and have segregated schools, then in a few more years Colorado would decide to do the same thing. So you see what is happening in your State this year will affect … all of us in the United States.”

“You and your parents should be very proud for few so young have a chance to do so very much for so many,” wrote Larry, Cher, and Diane of Minneapolis.

This letter addressed to "Little Leona & Family" came from Lawrence E. Fraley, Jr. of Boulder, Colorado. (THNOC, 90-76-L)

Some messages were for the students’ parents, such as William Henry Bracey’s card, which stated “You have taken a big step toward the betterment of your child’s education, and I feel safe in stating that, ‘From Louisiana came the greatest Negro the World has ever known.'”

And many were anonymous: “A very merry Christmas, Leona, from some people who are very proud of you. Americans everywhere owe you a great deal.”

The Future of the McDonogh 19 School

Today, as head of the Leona Tate Foundation for Change, Tate is focused on transforming a site known for hatred and pain into one heralded for community and inclusion.

Leona Tate is shown at the Lower Ninth Ward Living Museum in 2019. (Photograph by Keely Merritt, THNOC)

Leona Tate is shown at the Lower Ninth Ward Living Museum in 2019. (Photograph by Keely Merritt, THNOC)

“When the three of us went into that building [McDonogh 19], it stirred up a lot of racism and a lot of changes,” said Tate. “And I really want it to be a place to heal.”

The LTFC purchased the McDonogh 19 school building at 5909 St. Claude Avenue in January 2020 and began renovations the following month. It’s scheduled to reopen in spring 2021 as the Tate, Etiénne, Prevost (TEP) Center. The new facility will provide low-income housing to seniors age 55 and older, a “commun-iversity” operated by the People’s Institute for Survival and Beyond, an exhibition space, and much more.

“I always say the racism started there,” Tate concluded, “and this is where it should end.”

Editor’s note:

From November 2020 to November 2021, THNOC will collaborate with the Leona Tate Foundation for Change and the TEP Center on events, and THNOC members who join or renew at the $100 level and higher can choose to contribute $50 of their membership fees to the TEP Center. Learn more about this partnership, and how you can help both institutions, here.