Joseph Will (left) and Ashanty Felipe (Photograph by Sydney Wessinger for THNOC)

We are students pursuing bachelor’s degrees at Xavier University of New Orleans. During the fall semester of 2022, we interned at The Historic New Orleans Collection. Under the guidance of Sarah Duggan, the project manager of the Decorative Arts of the Gulf South research project, we contributed to the Black Craftspeople Digital Archive. Founded in 2019, the BCDA is a collaborative project that brings students, scholars, archivists, and the public together to research and highlight the history of an important but underexamined group: Black craftspeople in the United States.

Our search for information about Black craftspeople began with combing through a list of craftspeople, retailers, and apprentices in the appendix of Furnishing Louisiana: Creole and Acadian Furniture, 1735–1835. We also examined a variety of sources including newspaper archives, genealogical records, and court documents. Of the people who appeared in those documents, three caught our attention: Jean Rousseau, Henry Ware, and Peter Johnson.

Jean Rousseau

Jean Rousseau was a member of New Orleans’s unique Black Creole population. Rousseau worked in the French Quarter and is listed in contemporary documents as an ébéniste or menuisier—French for “cabinetmaker” and “carpenter,” respectively. Like many craftspeople of the 1800s, Jean Rousseau employed apprentices. Most apprentices were free people of color, but Rousseau attained the service of at least two enslaved men in his shop. Unlike the other apprentices, these two workers are not listed with their surnames. Instead, only their first names appear on surviving documents: Mars and Lolo. Jean Rousseau had at least 24 Black apprentices; most Black craftsmen had no more than a handful of apprentices. Rousseau’s large number of apprentices is likely a testament to his skill as a carpenter and a cabinetmaker.

Compared to many other Black craftspeople of the 19th century, Rousseau is relatively well documented. Still, in researching his life and work for the BCDA, we ran into difficulties. One was language. Even after the Louisiana Purchase, Louisiana maintained its French culture and language—including in public documents. Many of the sources related to Rousseau and his apprentices were written in French, which added the extra step of translation to the research. Spelling is another challenge. 19th century publishers and printers often shortened people’s first names, presumably to save space, and sometimes surnames were spelled differently in different documents. To do a complete search for Jean Rousseau, we also looked for “Jn. Rousseau” and the even shorter “J. Rousseau”; one apprentice, Severin Latapy, appears as “Mr. Severin Latapie” in a newspaper ad.

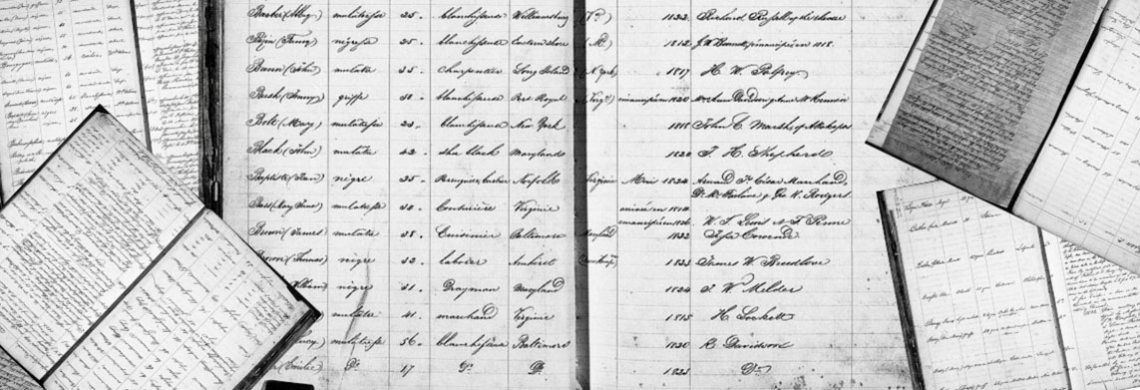

Between 1840 and 1856, all free people of color who were not born in New Orleans, or who were born enslaved in New Orleans and later emancipated, were required to register with the mayor’s office, as seen in this section from the “Register of Free Colored Persons Entitled to Remain in the State.” (Courtesy Louisiana Digital Library)

Our experience searching for information about Rousseau highlighted an important, if frustrating, truth about this type of historical investigation: sometimes, we cannot find the answers we seek. The 1823 newspaper ad that misspells apprentice Severin Latapy’s name states that Rousseau left his workshop in New Orleans for some time, putting Latapy in charge. Where did he go? Why did he choose Latapy to manage the workshop for him? What did Latapy and the other apprentices do after their training? We could not find out more about Rousseau's trip, or Latapy’s life or work. In fact, outside of public censuses published in newspapers and other indexes, additional records regarding Rousseau’s apprentices have not been found. Their stories may be lost to us.

Henry Ware

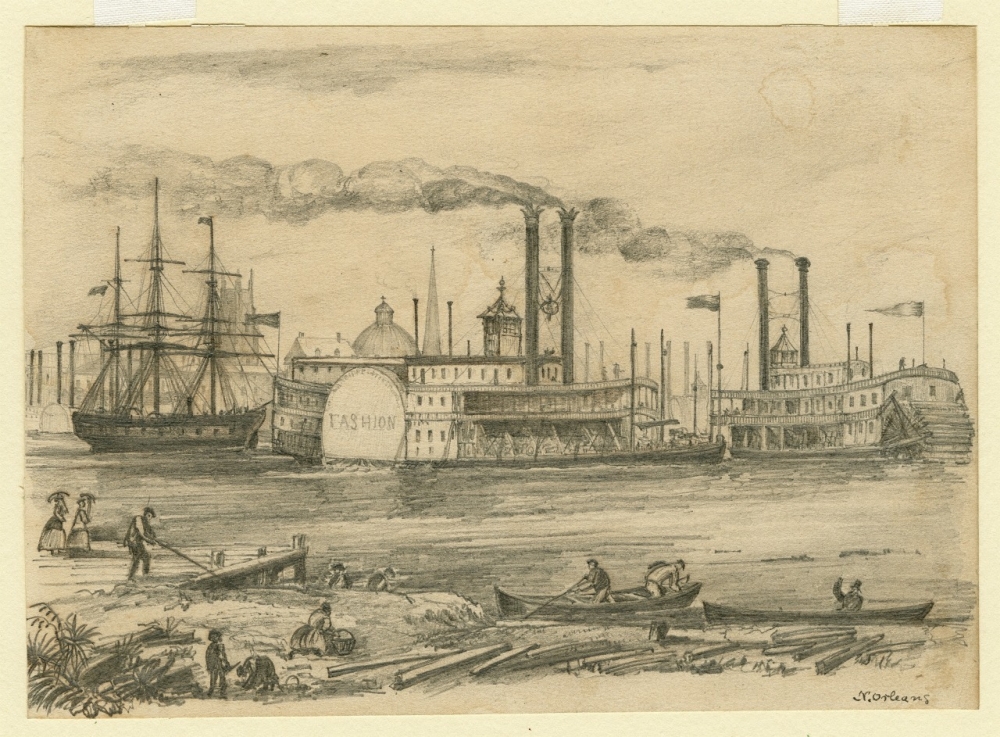

Henry Ware was born in Essex County, Virginia, in 1811, and moved to New Orleans in 1830 to work as a boatbuilder.

We did not find much information about Ware’s life before his move to New Orleans. In the BCDA database, we searched for the names that appeared near Ware’s in source documents, hoping to find a connection to other known Black craftspeople. In genealogical records, we searched for men born in Essex County and Virginia more widely. We searched records hoping to find out if Ware came to Louisiana alone, or with others. We were able to narrow our searches using what little info we did have on Ware and his community. Though many people migrated from Virginia’s Middle Peninsula, few moved from Essex County specifically. Though Ware’s name was quite common, his occupation was not; he was the only boatbuilder we came across in all our research. At every turn, we reached a dead end.

We were able to find slightly more information about Ware’s life after his move to New Orleans. An 1866 article in one newspaper reports the details of a court case that involved Ware. Ware successfully argued that Oscar H. Burbridge had illegally seized 550 bales and bags of cotton from him after a business dispute. Other articles mention the lengths Ware went through to find some form of justice.

What do not appear in newspaper records or other sources we found are answers to our questions about Ware as a person, or about the rest of his life. Did he ever go back to Virginia? Why did he leave in the first place? As with Rousseau and his apprentices, our research into Ware left us with more questions than answers.

Drawing of a New Orleans port scene, ca. 1866 (THNOC, 1947.23.9)

Peter Johnson

Peter Johnson was born into slavery in New Orleans. Peter’s owner, William Johnson, was a free man of color—and also his father. At age 13, Peter was emancipated. Eight years later, Peter registered as a cooper. He lived with his wife, Theresa, and their children, including a son named William.

Johnson appears in an 1852 newspaper article, where he is described as a having a large “hawk-like” nose and as speaking and singing loudly in both English and French.

Searching for information on Peter Johnson led us down another interesting path. We found a “Pedro Johnson” who lived with his family in the home of Cecilia Narcisse, a mixed-race Cuban woman. Like Peter Johnson, Pedro was a cooper and had a wife named Theresa and a son named William. Based on similarities between names, dates, and biographical information, we suspected that Pedro Johnson and Peter Johnson might be the same person. The inconsistencies in records might, we thought, be because of simple errors or miscommunications. The name difference might simply be a translation issue; Pedro is Spanish for Peter.

As it turned out, we did not find any information to definitely prove that Peter and Pedro Johnson were the same person. In the end, we concluded that Pedro and Peter Johnson’s similarities are coincidental; they were two different men.

Joseph and Ashanty at work (Photograph by Sydney Wessinger for THNOC)

Throughout our research, we ran into hurdles. So far, we have been unable to unearth enough information to paint full pictures of these Black craftspeople or their lives in New Orleans; we may never be able to. But that does not mean our endeavors were pointless, or even unsuccessful. Jean Rousseau, Severin Latapy, Henry Ware, and Peter—and Pedro—Johnson are only a few of the many Black craftsmen who lived and worked in 19th Century Louisiana. They deserve our respect, and recognition for how their work has contributed to the history and culture of the American South.

Header image: pages from the “Register of Free Colored Persons Entitled to Remain in the State” (Louisiana Digital Library)