In January 1955, a group of African American women gathered at 2100 Dryades Street to form the Metropolitan Women’s Voters League (MWVL). Their purpose, as stated in the Louisiana Weekly, was to register “every eligible woman who desires to become a voter.” The meeting took place at Katie’s School of Beauty Culture and Barbering, and the group appointed the owner, Katie E. Whickam, as chair. Under her leadership, the MWVL launched a voter registration drive, canvassing door to door and running voter education workshops. They were supported by the National Democratic Committee and hoped to register 100,000 Black voters in New Orleans and across the state. The Louisiana Weekly predicted “women of the community are going to participate like never before.”

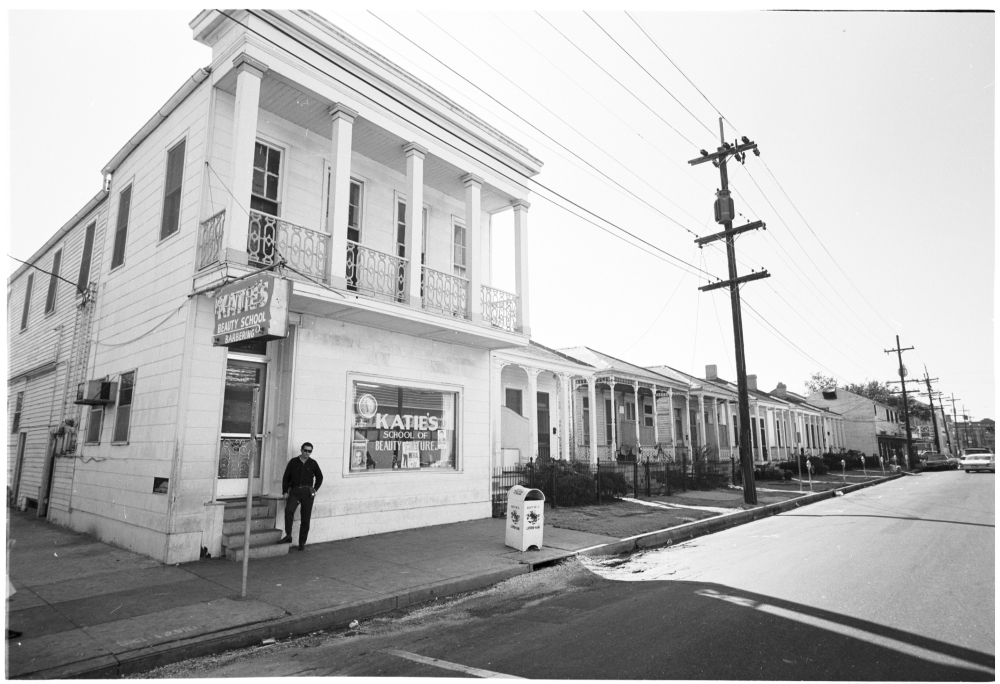

Katie’s School of Beauty and Culture at 2100 Dryades Street (THNOC, 1976.31.161 i,ii)

A beauty school might seem an unlikely place to launch a Black women’s voting league, but historian Tiffany Gill explains that African American beauticians were “key political mobilizers” in the modern Civil Rights Movement. Gill argues that as independent operators who relied solely on African American customers, Black beauty culturists (as beauticians were often called in the 20th century), beauty shop owners, and beauty school teachers and proprietors remained outside of the control of white employers. Their salons and schools, as segregated spaces, offered Black women a place to speak freely and organize safely. Katie’s School of Beauty Culture and Barbering provided exactly that kind of space for Whickam and the founding members of the Metropolitan Women’s Voters League.

The intersection of Whickam’s professional life and political activism extended beyond founding the MWVL. Two years later, she became president of the National Beauty Culturists’ League Inc. (NBCL), a professional organization for Black beauticians, based in Washington, DC. Whickam used this platform to encourage Black women in the industry to advocate for access to the ballot and for civil rights. As NBCL president, she built relationships with major leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and national Democratic Party politicians, including John F. Kennedy. Through her efforts in New Orleans and beyond, Whickam exemplifies the vital role beauticians played in the Black freedom movement.

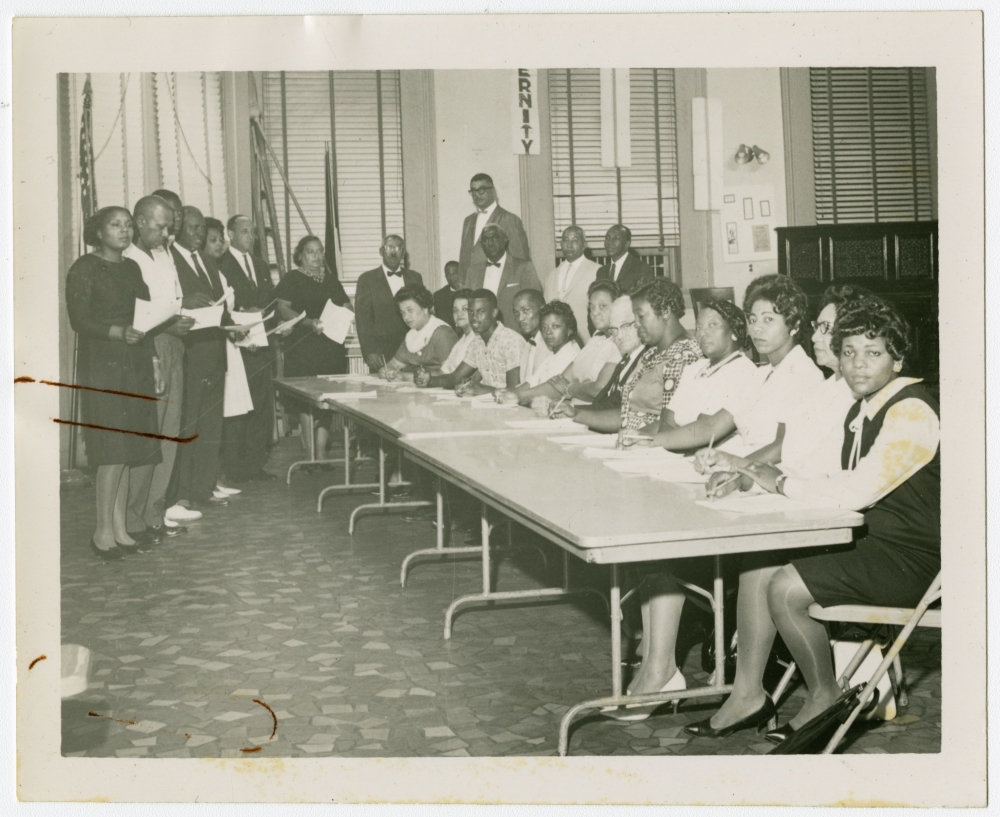

Officials of the Kennedy-Johnson Voters League in 1960 (from left: A. P. Tureaud, Rev. Avery Alexander, Ellis Hull, Katie E. Whickam, unidentified, and Jackson V. Acox) (courtesy of City Archives and Special Collections, New Orleans Public Library)

Born in Assumption Parish on March 12, 1903, Katie Ethel Whickam was the daughter of Minerva Pleasant Whickam and Rev. John C. Whickam. As a teenager, Whickam worked as a cook for a family in Assumption Parish. By 1930, she was married to her first husband and living in New Orleans. Over the next decade, Whickam’s marriage ended in divorce, and she left New Orleans to train as a cosmetology teacher at the Orchid School of Beauty Culture in New York City. She returned to New Orleans to teach beauty school. She also went to Gilbert Academy’s evening school, from which she graduated in 1942, and attended classes at a local HBCU, Xavier University. Three years later, she married Leonard Chapman. Whickam also studied abroad, graduating from the L’Oréal Beauty School in Paris in 1957 and obtaining further instruction in Rome. In 1959, she received an honorary doctorate degree from Leland College, after which time she was often referred to as Dr. Katie E. Whickam. During this time, Whickam adopted and raised three children.

When she founded the MWVL in 1955 Whickam had been an established beauty school proprietor for over a decade. Fifteen years earlier, in 1940, she was teaching at the Poro School of Beauty Culture. Within two years, Whickam had opened Katie’s School of Beauty Culture and Barbering. The school offered day and evening classes in a variety of skills, including hair styling, cutting, and coloring, as well as special workshops. The numerous graduates of Katie’s School of Beauty Culture and Barbering remained in contact through their own alumni association.

In addition to teaching and running a successful business, Whickam was actively involved in furthering the beautician profession for Black women. In 1947, she helped found the Louisiana State Beauticians’ Association (LSBA) and served as the organization’s first president. In addition to holding workshops and an annual convention, the LSBA also had a political purpose. In the 1930s, states began to regulate hair care businesses, requiring state licenses, certifications for beauticians, and regular approval from newly created boards of inspectors. Organizations like the LSBA worked to provide Black beauticians with a voice in government involvement in their industry and pushed for representation on state inspection boards. This was important because the beauty culture sector as a whole was segregated along racial lines, and Black beauticians outnumbered white beauticians in many states. Gill explains that organizations like the LSBA “saw the need for individual representation on state beauty boards as a way for them to begin to challenge discrimination in state and local governments more generally.”

Whickam speaking at the National Beauty Culturists’ League annual meeting in New Orleans (courtesy of Libby Neidenbach)

Whickam’s work with the LSBA served as an entrée into politics. In 1956, she became one of four Black Louisianians named as state inspectors. Yet, within six months, Gov. Earl Long cut the positions, citing a lack of funds. In 1959, Whickam joined 200 fellow LSBA members in picketing the state capitol. The beauticians complained that Governor Long had not fulfilled his campaign promise to appoint Black state inspectors. They also accused the Louisiana Board of Control of Cosmetic Therapy of failing to investigate unauthorized businesses, which was hurting licensed practitioners and shop owners. For Whickam, the solution to these issues lay with the ballot box. She told the crowd of protesters, “Just go home, and work on your registration at the polls. If [Long] runs again, we’ll fix him.”

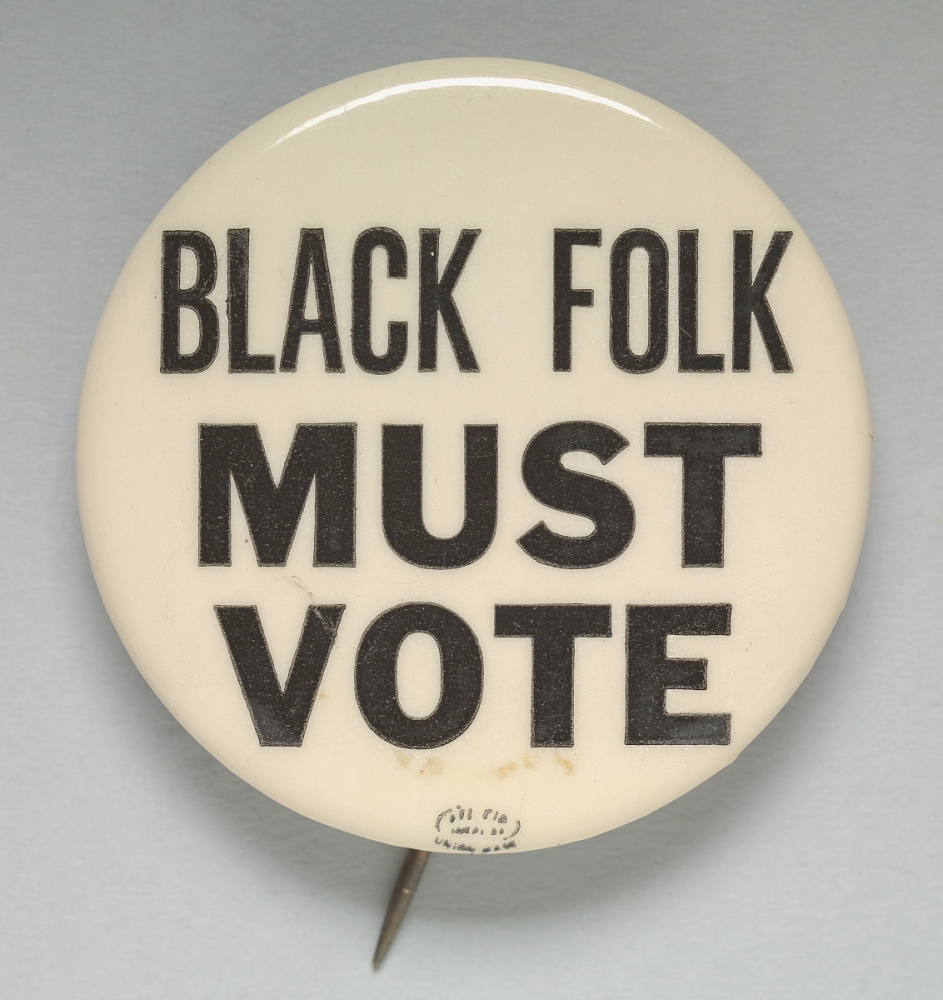

Pinback button, ca. 1965 (courtesy of the Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, gift of Kenneth A. Smaltz Jr.)

The importance of voting rights and participation at the polls was a message Whickam would relay time and again—locally, as president of the Metropolitan Women’s Voters League, and nationwide, as president of the National Beauty Culturists’ League (NBCL), a position she held for two-and-a-half decades. The role of the NBCL, she understood, went beyond supporting Black business professionals; it was about helping achieve first-class citizenship for all Black Americans.

The first NBCL annual convention over which Whickam presided took place in New Orleans in August 1957. The 11-day conference, held at Booker T. Washington High School, included training sessions with the National Institute of Cosmetology, business meetings, speakers and panels, competitions, parties, a church service, and a banquet. Over 500 beauticians from 39 states and the Bahamas attended the convention.

“Beauticians should register and vote and make an effort to have every customer a registered voter,” Whickam declared in 1957, as part of her opening remarks to the NBCL annual convention, held in New Orleans. Her directive set the stage for the convention’s civil rights program, entitled “The Role of Beauticians in the Contemporary Struggle for Freedom.” The program consisted of a slate of speakers, including Daniel Byrd of the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund; Rev. A. L. Davis, founder of the Orleans Parish Progressive Voters League; and Clarence Laws, NAACP field secretary. Laws spoke passionately about the right to vote as “a great fundamental right which must be defended to the fullest measure of our devotion.” He ended his speech with a call to action for the attendees to become involved in politics on local and national levels.

The highlight of the civil rights program, however, was an appearance by Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., who had successfully led the Montgomery bus boycott the previous year and had recently founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). King spoke about the hard work that integration would require. “I am not so optimistic as to believe that integration is ‘just around the corner,’” King said. “We have come a long, long way and we still have a long way to go, but we must keep moving in spite of delay tactics used by segregationists.” He argued for the necessity of legislation to end segregation and that it was essential that “all participate in the struggle for freedom and gain the use of the ballot.”

Dr. King understood the organizing potential of beauticians in the fight for civil rights, especially when it came to “get[ting] folk out to vote.” He connected Whickam to Ella Baker, the associate director of the SCLC, and in October 1958 Whickam was elected to the SCLC’s executive committee. The following year, she became the first woman to hold a staff officer position when she was elected assistant secretary. “This is in keeping with the expressed need to involve more women in the movement, and we believe that Mrs. Whickam will bring new strength to our efforts,” Baker wrote in announcing Whickam’s position. “The National Beauty Culturist’s League Inc., of which she is president, has strong local and state units throughout the South, and voter registration is a major emphasis to its program.”

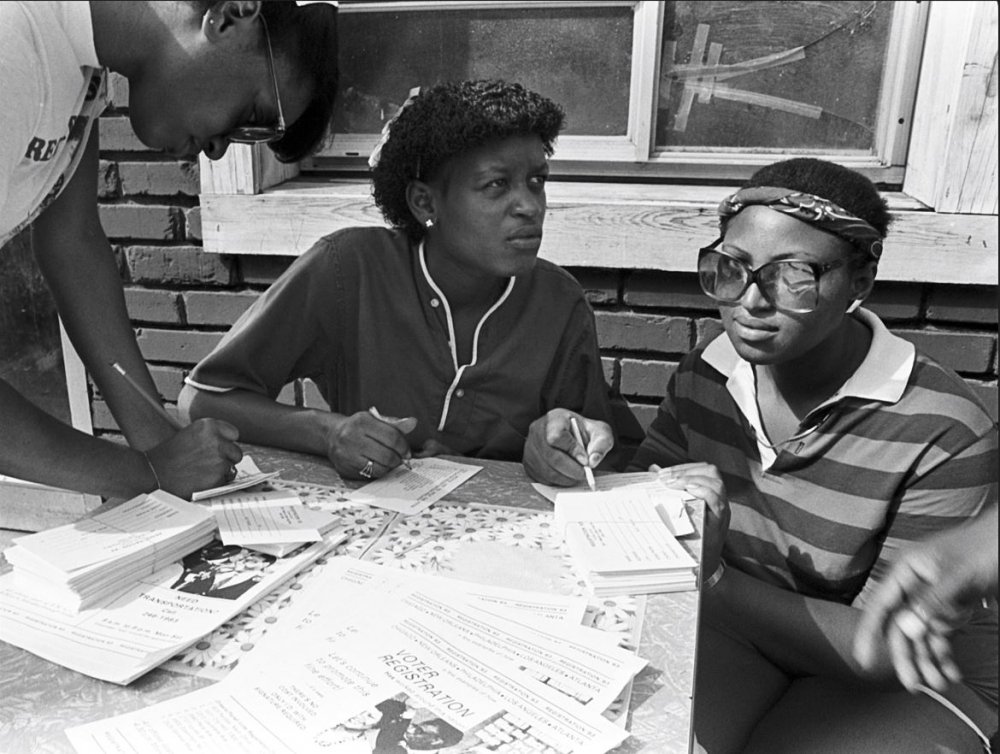

Whickam’s national leadership role did not detract from her continued activism on the local level. As president of the MWVL, she spoke at rallies, oversaw voter registration drives, and operated a voter registration school. Between 1960 and 1962, Louisiana legislators passed new laws that made registering to vote more difficult. Registrars used these new rules, like a multiple-choice “citizenship test,” to reject Black applicants. Voter registration schools prepared Black New Orleanians to navigate the difficult registration forms. In the early 1960s, the MWVL operated a voter registration school in Katie’s School of Beauty Culture and Barbering.

Voter registration school at the Scottish Rite Temple in 1964 (courtesy of the Amistad Research Center)

In addition to voter registration, Whickam and the MWVL were involved in electoral politics through the endorsement of candidates. In 1960 the MWVL joined with three other Black voter organizations in the city to create the Kennedy-Johnson Voters League, which campaigned for the Democratic presidential ticket in the city and across the state. Whickam served as secretary for the group—the only woman in a leadership position.

Whickam’s strong support for John F. Kennedy, whom she met when he was a senator in 1959, led to an appointment as a consultant to the Office of Civilian Defense and Mobilization in 1961. Two years later, she was one of several hundred women invited to the Kennedy White House to discuss civil rights issues. President Kennedy urged the women and their constituents to support his civil rights bill and to participate in interracial human relations groups in their local communities. Following Kennedy’s assassination, Whickam continued to support Lyndon B. Johnson. She was invited to the White House for a conference after Congress passed the 1964 Civil Rights Act and was called upon to encourage NBCL beauticians to campaign for Johnson later that year.

Throughout the 1960s, Whickam continued to lead the NBCL with a focus on civil rights. At the organization’s 1964 convention, Whickam again urged attendees to foster voter registration. “In this way,” she said, the NBCL “will directly touch and advise nearly two million Negro women in the nation.” In response to the numerous riots that erupted in urban centers throughout the summer of 1967, she said “proper use of the ballot,” not violence, was the solution.

Whickam served as NBCL president for 27 years. When she was reelected again in 1981, she told the Times-Picayune that the position was “a full-time, nerve-wracking job that has become a part of me. I love it.” During her tenure, Whickam grew the league’s membership from around 9,000 to over 40,000 beauty culturists. She oversaw the multimillion-dollar construction of a facility for the National Institute of Cosmetology and the NBCL headquarters, both in Washington, DC. Whickam became president emeritus in 1984. She died at age 87 on February 2, 1988.

Dr. Katie E. Whickam never wavered in her belief that “you can cure all evils with the almighty ballot.” As a beauty culture leader, Whickam left a legacy of activism and advocacy for full political participation by all American citizens.

Women registering to vote in 1983 (THNOC, gift of Harold F. Baquet and Cheron Brylski, 2016.0172.1.204.1)

About The Historic New Orleans Collection

Founded in 1966, The Historic New Orleans Collection is a museum, research center, and publisher dedicated to the stewardship of the history and culture of New Orleans and the Gulf South. Follow THNOC on Facebook or Instagram.