While the New Orleans riverfront boasts one of the largest New Year's Eve fireworks shows in the country, it was the rate of falling bullets that made headlines in the mid-1990s. That’s when the tradition of celebratory gunfire was rampant in the city, even making its way to The Historic New Orleans Collection.

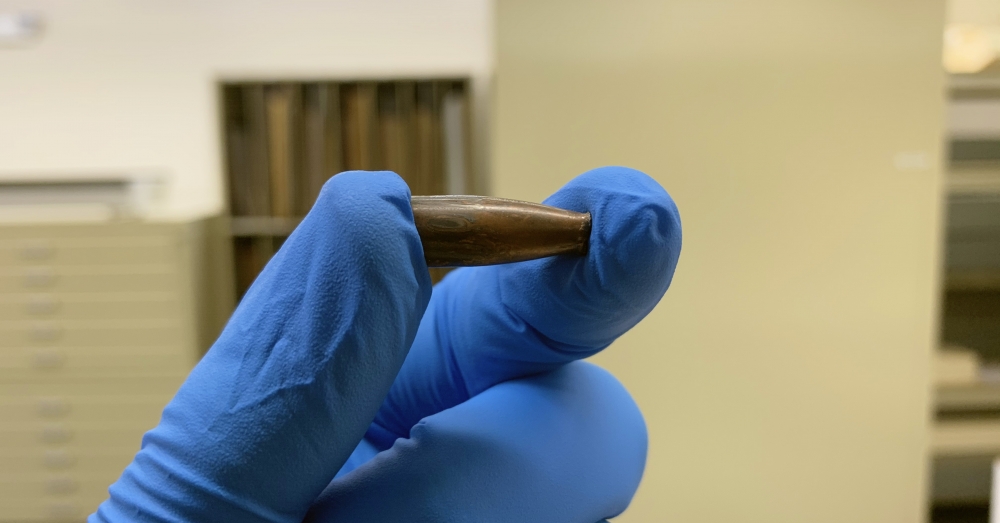

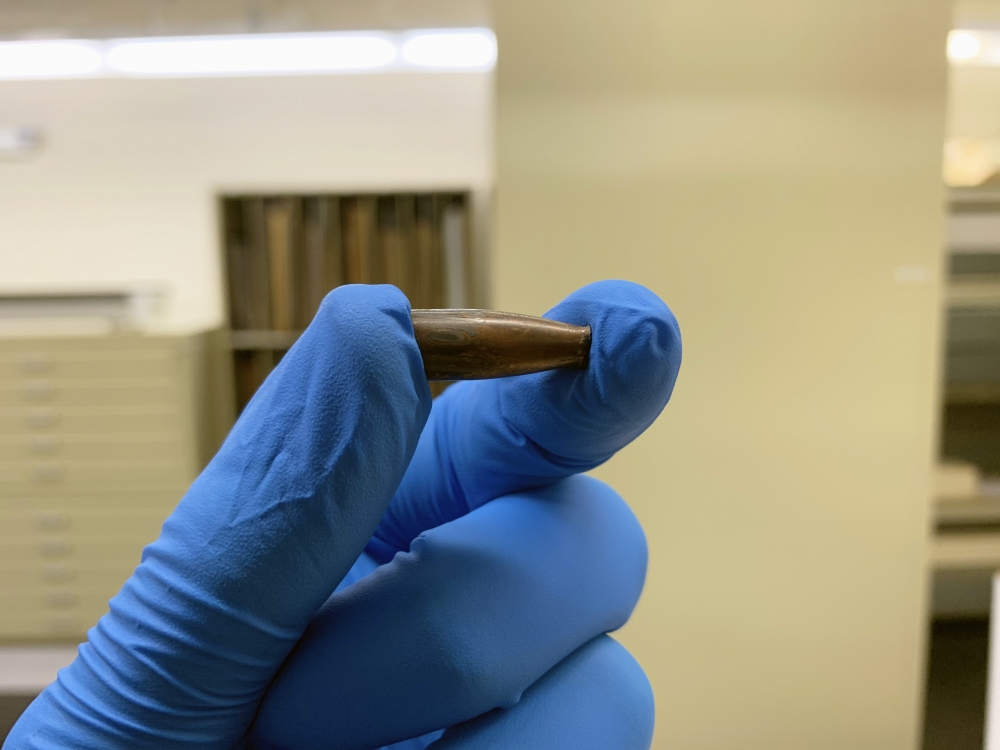

On January 2, 1997, a bullet was found in our courtyard at 533 Royal Street. Dusted with brick particles, it is now in the archive at the Williams Research Center, a reminder of a particularly fraught chapter in the history of New Year’s Eve celebrations in the city.

The bullet found in THNOC’s 533 Royal Street courtyard is now preserved at the Williams Research Center. (photograph by Eli A. Haddow; THNOC, 1997.11)

Americans have fired guns in the air to celebrate New Year's for over a century, and New Orleans is no exception. On New Year’s Eve in 1911, a young Louis Armstrong was arrested for firing his stepfather’s gun in the air.

But more recently, celebratory gunfire caused a public safety crisis. On New Year’s Eve 1994, while watching fireworks on the riverfront, a Boston tourist named Amy Silberman was killed by a falling bullet.

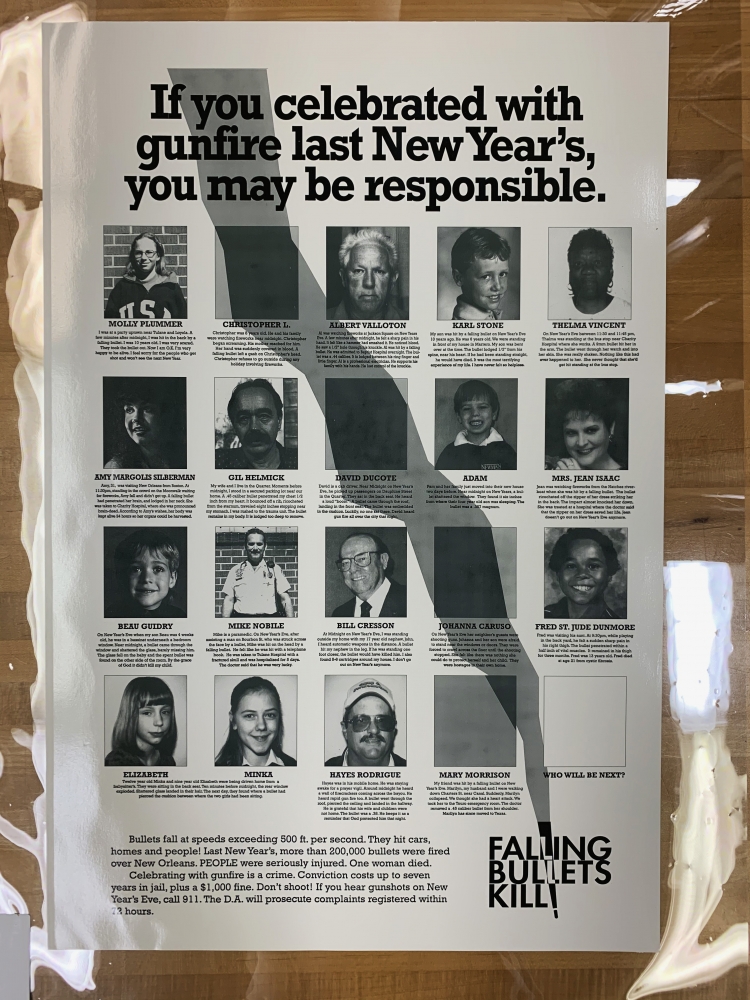

According to a 2007 article in the Times-Picayune, the New Orleans Police Department estimated that 200,000 rounds of ammunition were fired into the air on the night that Silberman was killed. In reaction, a public safety campaign in 1995 featured signs declaring that “Falling Bullets Kill.” Each sign featured portraits of 15 victims of gunfire with the inscription “WHO WILL BE NEXT?” A 1996 article in the New York Times reported similar public safety campaigns across the country that were attempting to stop a tradition that had persisted since the late 19th century.

A poster for a public safety campaign against celebratory gunfire shows portraits of 15 victims of all different ages, including Amy Silberman who was killed, with the inscription: Who Will Be Next? (THNOC, 1997.9)

“This was a period when firing guns on New Year’s got really out of hand,” said John H. Lawrence, THNOC’s director of museum programs, who worked here when the bullet was found. “I can remember going to a party on New Year’s Eve on Bayou St. John, and people were firing machine guns into the water.”

The bullet found in our courtyard is a reminder that this tradition did not immediately stop, despite the campaign. It was former THNOC employee Doug MacCash—now a writer for the New Orleans Advocate |The Times-Picayune—who found a bullet lying on the courtyard bricks in 1997. MacCash said that he doesn’t remember making this specific find but that it would not have been an isolated incident for him.

The courtyard at 533 Royal Street, where the bullet was found.

“Around that time, [finding a bullet] was like finding a four leaf clover,” said MacCash, in a recent phone call. “I was having roof work done at my house, and the roofer found a couple of bullets in the gutter, so I was definitely attuned to finding them in places. It was always a sort of grim moment when I found one, because imagine how many have to fall for you to find one, right?”

According to Nola.com, the rate of gunfire dwindled by the time Hurricane Katrina struck, but on New Year’s Eve 2005, reports peaked again. The next December, the city provided EMS units with combat helmets to be worn 15 minutes before and after midnight. That evening a bullet penetrated the back of an ambulance, injuring no one, but reminding the two paramedics aboard that they ought to take the threat seriously.

Since then, reports of gun shots on New Year’s Eve have fallen again, and though the problem is not unique to New Orleans, the last 30 years show how a dangerous 19th-century tradition has continued to affect the city in the modern day.