Ever since the first large-scale Mardi Gras parade rolled through the streets of New Orleans—the Mystick Krewe of Comus’s torch-lit tribute to Paradise Lost on February 24, 1857—Carnival has been canceled a total of 14 times, whether officially by the city or unofficially by the krewes themselves. The annual celebration has been suspended because of war, epidemics, mob violence, and labor disputes.

The front page of the Times-Picayune carried the news that krewe captains had canceled their parades in 1979, the last time parades were canceled.

On November 17, 2020, the City of New Orleans announced that, due to COVID-19, parades would not be allowed to roll in 2021. As New Orleans braces for this vastly downsized celebration, THNOC is looking back at each cancellation—the years the good times didn't roll—focusing on what the city was like at that time, the activities of the krewes during the downtime, and the celebrations that did take place despite the shutdown of big parades. After all, can you ever really cancel Mardi Gras?

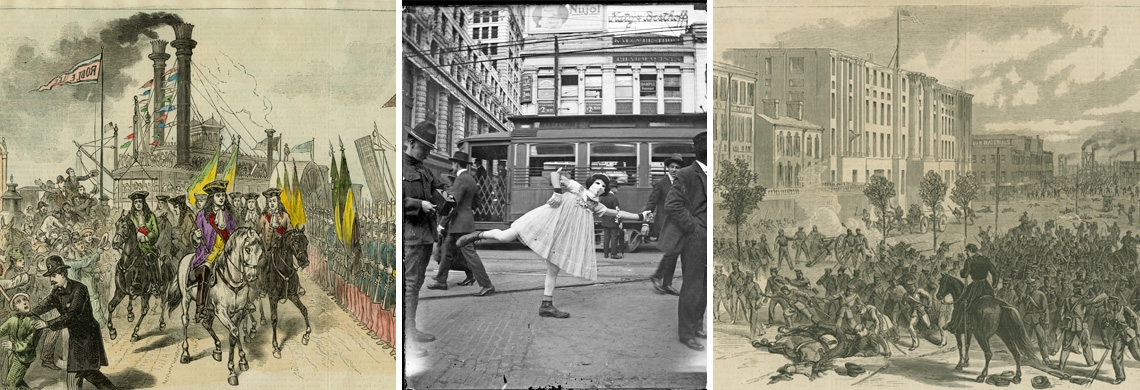

The American Civil War: 1862–65

Comus was the only official Mardi Gras krewe in existence at the start of the Civil War and wouldn’t hold another ball until 1866. This invitation was created for the 1862 ball, which was canceled. (THNOC, The L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1957.95)

In February 1862, staring down a military mobilization that would result in the occupation of New Orleans by May, Comus canceled its Mardi Gras Day ball with a proclamation citing the “general anxiety” of the time. An anti–Mardi Gras editorial, published February 19 in the Daily Picayune, spoke directly to the women of New Orleans, imploring them to remember the “noble sacrifices” of Confederate soldiers: “Dance not over these victims, but on the day which precedes the season of fasting and prayer, let no sounds of revelry be heard.” The krewe did not have another Carnival ball until 1866.

It is generally stated that Mardi Gras did not take place during the Civil War years, but that doesn’t mean there were no Carnival celebrations of any kind. It is true that the members of elite antebellum social clubs like the Boston and Pickwick Clubs refused to participate, as they were loyal to the Confederacy, but other social groups, including immigrants and those with Union sympathies, did take part in the celebrations.

In the final two years of the war, Mardi Gras was officially sanctioned by Union commanders, and the lavish bals masques that took place were managed by people and associations with ties to the Union army, including Masonic groups, fire companies, and General Banks’s wife herself. The Young Men’s Benevolent Association (not to be confused with the Young Men Olympians Junior Benevolent Association, the second oldest benevolent society in America), gained a reputation for throwing the best masquerade balls during the war, held at places like the French Opera House on Bourbon Street, the Masonic Grand Lodge at St. Charles and Perdido Streets, and the St. Charles Theater.

A newspaper illustration depicts a masquerade ball thrown by the wife of Union General Nathaniel Banks in celebration of Washington’s Birthday on February 24, 1864. (THNOC, gift of Harold Schilke and Boyd Cruise, 1953.75)

A newspaper illustration depicts a masquerade ball thrown by the wife of Union General Nathaniel Banks in celebration of Washington’s Birthday on February 24, 1864. (THNOC, gift of Harold Schilke and Boyd Cruise, 1953.75)

News reports from the period remark on the relative success of these celebrations, though it is certain that the press was being monitored by the Union commanders. Mardi Gras 1864 featured more celebrations than the city had seen since the occupation began, but in the days that followed, some claimed that the “fun was a farce,” and that the mood was melancholy.

Others said the “balls were merry, the bars were full,” and that Canal Street was packed to an “unwonted extent” with maskers. “Amid the whirl of gay dancers and voluptuous music the hours passed merrily away,” one Daily Picayune columnist wrote. However, such revelry was only permitted on Mardi Gras Day itself; according to several news reports, anyone caught “playing Mardi Gras out of season,” which could include masking or cross-dressing, could be thrown in jail.

On February 13, 1866, Comus returned to celebrate Mardi Gras with the theme “The Past, The Present, and the Future” and a ball at the Varieties Theater. As much as New Orleans society yearned for a return to normalcy after the war, Reconstruction would forever change the city. The next decade would bring escalations of racial and political tension, erupting in violent clashes between citizens, police, and militiamen, causing Mardi Gras to be canceled once again.

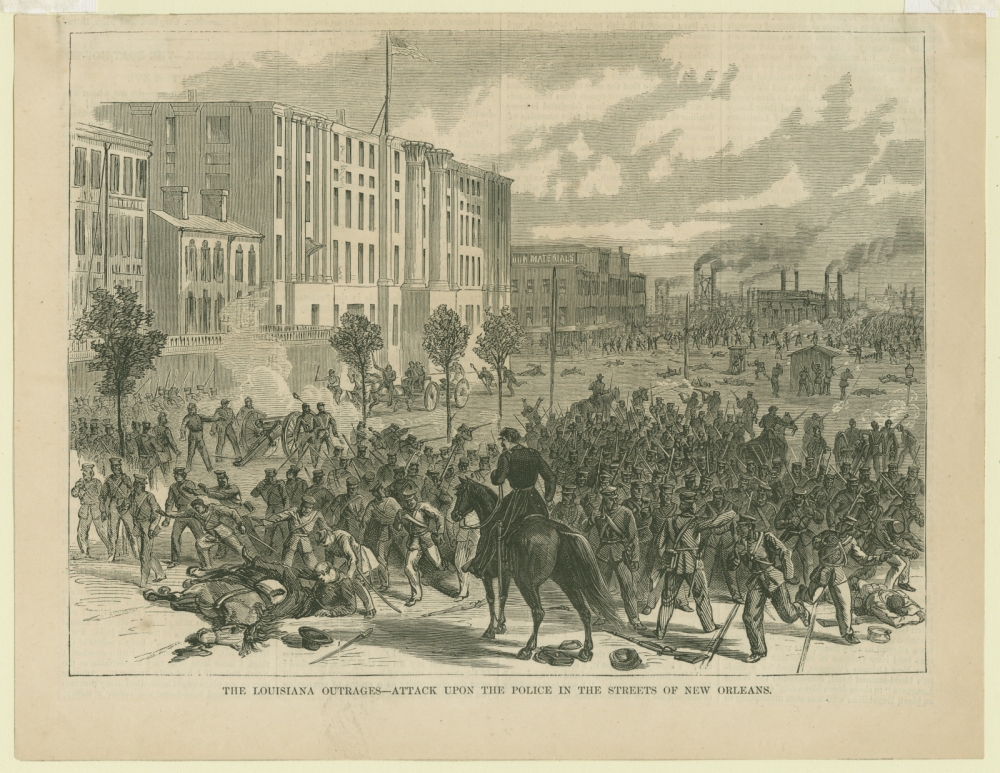

White-Supremacist Violence: 1875

This invitation to the Twelfth Night Revelers’ 1875 Mardi Gras ball was issued before the event was called off. The group made the decision to cancel their ball when additional federal troops arrived to impose order on the city after violence erupted in the streets in September 1874. (THNOC, the L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1960.14.88)

Reconstruction in New Orleans was marred by political factionalism, white-supremacist violence, and disputed elections, all stemming from emancipation and the increasing involvement of African Americans in politics, the economy, and society in general. Against this complicated landscape, several new krewes formed in the postwar period, including the Twelfth Night Revelers in 1871, as well as Rex and Momus in 1872.

The members of these new Carnival krewes were wealthy Anglo-American elites and Southern Democrats, and they used their 1873 parades and tableaus to ridicule and criticize the Republican government, taking aim at impeached Governor Henry Clay Warmoth and his ally, Metropolitan Police Superintendent Algernon Sidney Badger. Comus’s infamously racist parade that year was themed “The Missing Links to Darwin’s Origin of Species,” and it depicted Warmoth as a snake, Badger as a bloodhound, and African Americans as monkeys. The spectacle prompted the Metropolitan Police to refuse to clear pedestrian traffic along the route, forcing Comus to end its parade early.

The political satire of Comus’s parade was a departure from the neutrality of previous years and is credited with establishing the satirical Carnival tradition that continues to this day. During this time the members of the city’s elite krewes began to consolidate cultural and political power, with the primary aim of toppling the Republican-led government. That effort would succeed, but it would come with a terrible human cost.

An illustration from Harper’s Weekly depicts the Battle of Liberty Place in which white supremacist militants overthrew Louisiana's Republican government. (THNOC, gift of Harold Schilke and Boyd Cruise, 1959.159.21)

On September 14, 1874, thousands of white supremacists calling themselves the Crescent City White League—including members of Rex and Comus, Confederate veterans, and other Democratic political supporters—attacked representatives of the Republican government, which they saw as illegitimate and instigating a race war. Over the course of three days, members of the White League defeated the Metropolitan police forces and the state militia in what was later dubbed by the victors the Battle of Liberty Place. After four days, President Ulysses S. Grant sent in federal troops to reinstate Governor Kellogg and occupy the city for the second time since the Civil War.

Perhaps owing to the presence of federal troops, or because of the shattered relationship between local police and the krewes, Rex and Comus canceled their balls and parades for the coming season. The Twelfth Night Revelers sent out an invitation to a masked ball but canceled the event in January with a public statement in the Daily Picayune.

Yellow Fever Outbreak: 1879

Though other krewes canceled their parades because of the yellow fever outbreak in 1879, Rex carried on in spite of it. This illustration depicts the arrival of Rex at the foot of Canal Street on Lundi Gras, 1879. (THNOC, 1974.25.19.79)

Though other krewes canceled their parades because of the yellow fever outbreak in 1879, Rex carried on in spite of it. This illustration depicts the arrival of Rex at the foot of Canal Street on Lundi Gras, 1879. (THNOC, 1974.25.19.79)

In 1878, over 4,000 New Orleanians died of yellow fever while the city and state government failed to respond to the crisis. It was the era before widespread sanitation infrastructure, and the cause of the disease was still misunderstood. The Louisiana State Board of Health refused to declare it an epidemic, so instead private groups like the Howard Association and the Dietetic Association of the Pickwick Club (which formed Comus) worked to feed the hungry, heal the sick by providing private doctors and nurses, and stop the spread of the disease by contracting drainage infrastructure.

After this devastating year, Comus, the Twelfth Night Revelers, and Momus did not parade, but other groups, including Rex and the recently organized Phunny Phorty Phellows, decided to parade as usual in February 1879. Amid the human suffering and quarantine-induced economic woes, many were offended by Rex’s move, including former Republican Governor P.B.S. Pinchback, who blasted the krewe in his newspaper, the Weekly Louisianian:

“Our commerce may go to decay...thousands of our citizens may fall victims to a wasting pestilence from our poverty to keep gutters, streets, and lanes but when cruel destiny brings us the mighty Rex, our very rags, like Aladdin’s lamp bring forth gold and ribbons and music and all the like to do homage to our omnipotent sovereign! Great is Mardi-Gras, but wondrously wise is New Orleans that can in her professed poverty maintain such a mighty monarch!”

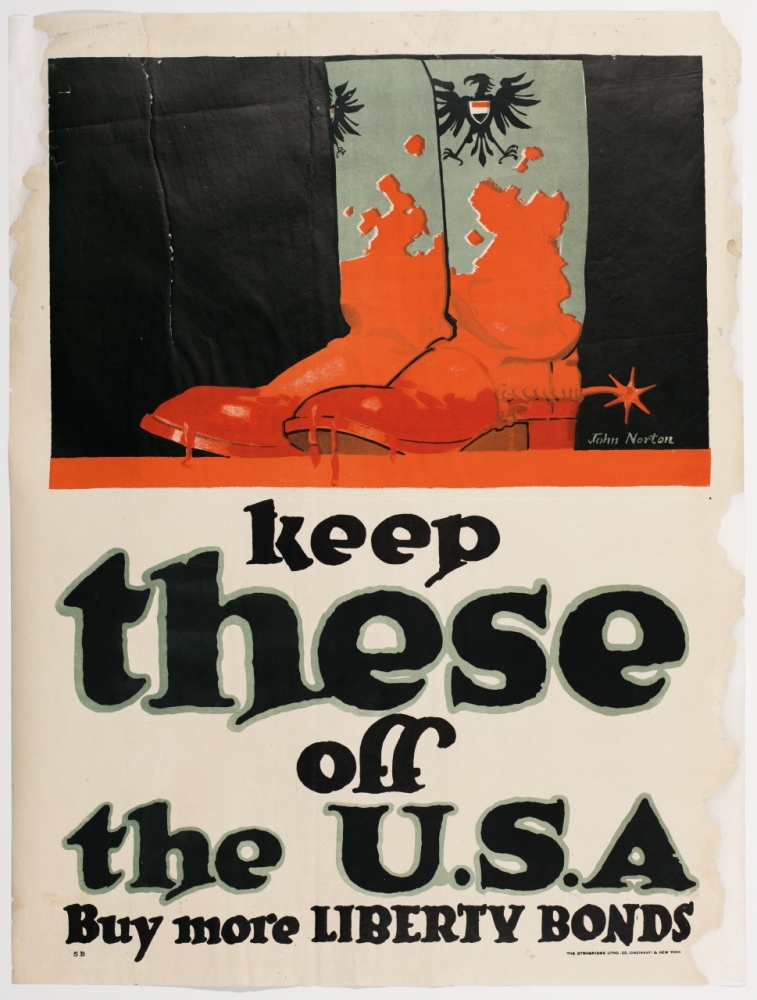

World War I: 1918

A poster advertising war bonds depicts bloodied German military boots. (THNOC, gift of Mrs. Francis Gary Moore, 1983.238.5)

The turn of the century saw the formation of many new Carnival organizations, including the Krewe of Proteus, the Atlanteans, and the Elves of Oberon. Traditionally excluded from membership in the old-line krewes, African Americans began forming their own Carnival organizations, such as the Original Illinois Club in 1895 and the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club in 1909. The first female club, Les Mysterieuses, was active only briefly, from 1896 to 1900, but paved way for the future of women’s Carnival organizations.

The US entered the First World War in April 1917, so it wasn’t until 1918, the final year of the war, that city officials announced the cancellation of Carnival. Knowing some people would still celebrate, Mayor Martin Behrman made a statement ahead of the festivities: “Now that the Mardi Gras season is approaching, I desire to repeat and to emphasize that masking of every kind and character will be strictly prohibited during that period in New Orleans. This regulation is deemed essential because of the war and the opportunity promiscuous and other masking would afford enemy aliens and other evil disposed persons to commit crime while thus disguised.”

Two days before Mardi Gras, the Times-Picayune reported that “no banners of purple, green, and gold are flying, it is true, but the Stars and Stripes have filled their place, and the flag of New Orleans has been raised.”

This image from November 11, 1918 shows the scene on Canal Street after the city recieved news of the Armistice that ended fighting in WWI. (THNOC, gift of Waldemar S. Nelson, 2003.0182.135)

Instead of Carnival parades, New Orleanians held Liberty Bond parades, which were quite successful, with the city exceeding its bond quota on every drive. And, of course, when the end of the war was announced November 11, 1918, the city quickly organized and carried out a large parade on Canal Street to celebrate.

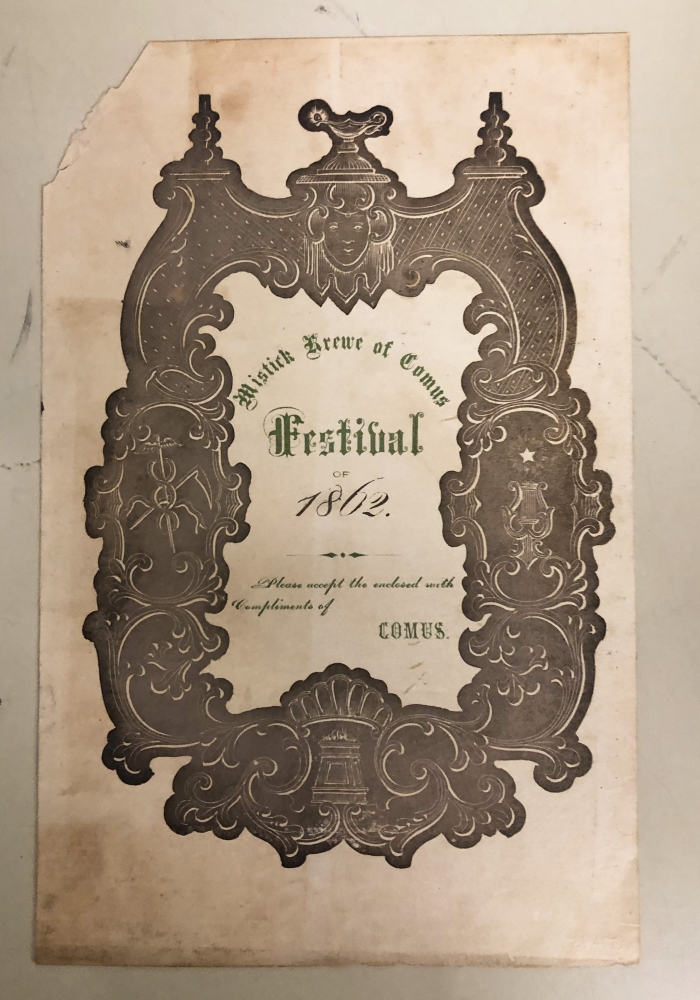

Spanish Flu: 1919

Although parades were called off due to the Spanish Flu epidemic, maskers still took to the streets to celebrate. (THNOC, gift of Waldemar Nelson, 2003.0182.159)

Though the end of the war brought about a joyous time, the winter of 1918 was marked by the spread of Spanish influenza. Much like today, newspapers reported daily case counts. From October 1918 to April 1919, New Orleans experienced over 54,000 cases of the Spanish flu, with nearly 3,500 deaths. The war may have ended, but New Orleans, along with the rest of the world, was still reeling from a deadly pandemic that would plague the city for two years. Although the Spanish flu wasn’t enough to cancel Mardi Gras on its own, it came at a time when the city was still recovering financially from the war.

So once again, parades and balls for the upcoming Carnival season were canceled. But this did not stop some New Orleanians from taking to the streets wearing masks and costumes on Mardi Gras Day. Although retail stores remained open for “business as usual,” Mayor Behrman announced that individuals could celebrate Mardi Gras if they pleased.

Smaller Carnival organizations, such as the Jefferson City Buzzards, the Easy Riders, the Magazine Market Swells, and the Mysterious Babies were among those that held impromptu street parades. The Loyal Order of Moose even held a masquerade ball Mardi Gras night. Photographer John Tibule Mendes documented the day in photographs, capturing costumed revelers on Canal Street as they commemorated the holiday amid a normal workday.

World War II: 1942–45

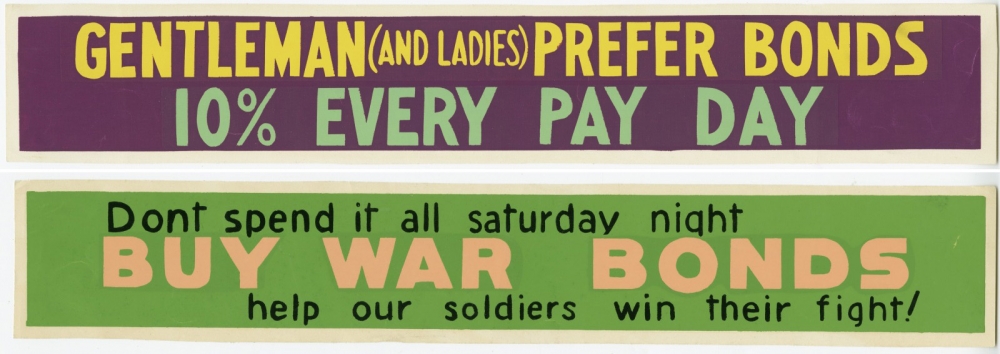

The top poster, a play on the title of the 1925 novel Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, is printed in Mardi Gras colors, possibly as an attempt to appeal to New Orleanians during the Carnival season. The bottom poster would have also been meaningful during Carnival, placing revelry and frivolous spending in opposition to the war effort. (THNOC, the Anna Wynne Watt and Michael D. Wynne Jr. Collection, 1981.203.4 and 1981.203.1)

The top poster, a play on the title of the 1925 novel Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, is printed in Mardi Gras colors, possibly as an attempt to appeal to New Orleanians during the Carnival season. The bottom poster would have also been meaningful during Carnival, placing revelry and frivolous spending in opposition to the war effort. (THNOC, the Anna Wynne Watt and Michael D. Wynne Jr. Collection, 1981.203.4 and 1981.203.1)

After 1919, Carnival krewes continued to roll until the United States entered the Second World War in 1941. For the next four years, there were no parades or balls while the city focused its energies toward the war effort.

Within a week of the country’s entrance into the war, city officials announced the cancellation of the 1942 Carnival festivities. “Floats, costumes and the gay ornamentations of next year’s celebration had been ordered,” the Times-Picayune reported. “But drapes were drawn over floats Friday, and soon the costumes will be shipped back to warehouses waiting a more happy, carefree day.”

The only formal Carnival ball held that season was an event to raise funds for relief work among families of enlisted men in the armed forces. Held Mardi Gras night (February 17, 1942) at the Municipal Auditorium and open to the white public, the ball was themed “The Americas” and was organized by the Army and Navy Club of New Orleans. Captains of various Carnival organizations collaborated to plan the tableau, which followed that of traditional Carnival balls.

In 1943 on Mardi Gras Day, March 9, the Million-Dollar War Bond Drive kicked off. Led by Leon Godchaux Jr., chairman of the Retailers for Victory committee, about 7,000 retail merchants in the city joined in the drive with the goal of selling one million dollars in war bonds and stamps. The effort was so successful that other cities around the country decided to hold similar drives on national holidays for the duration of the war.

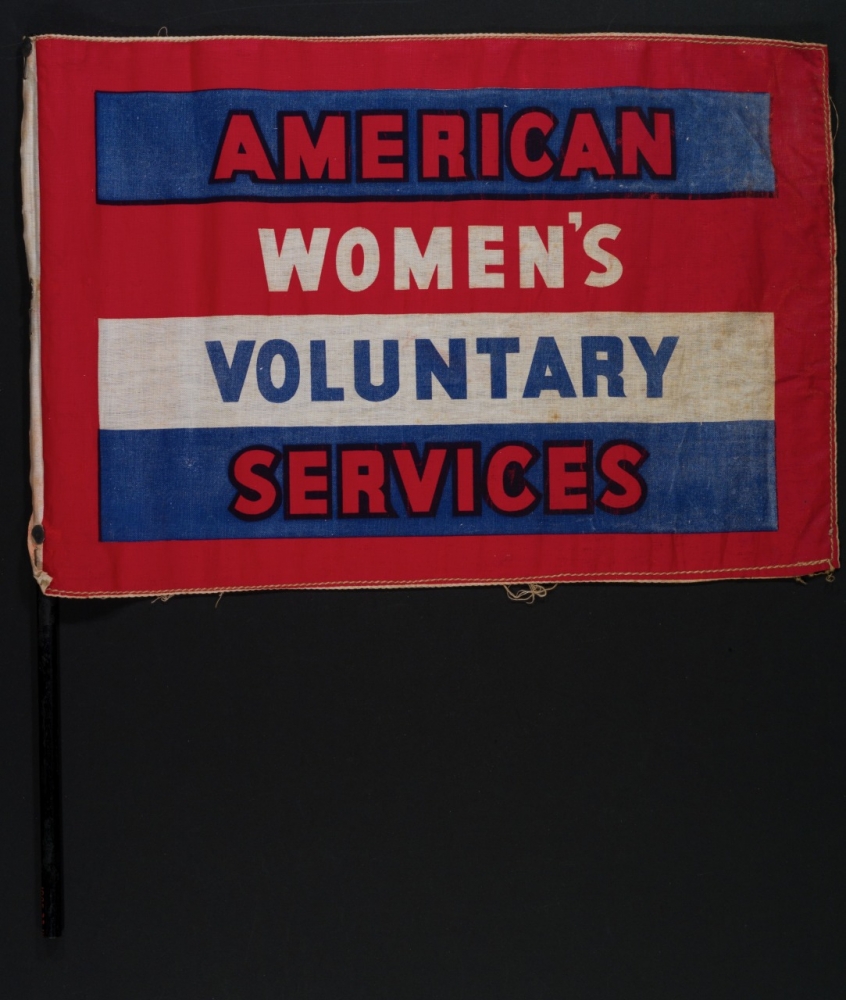

The city’s capacity for Carnival organizing helped the troops in other ways, too. Shortly after Mardi Gras 1943, Private Leroy Leatherman of Louisiana, based at an army camp in San Luis Obispo, California, wrote the American Women’s Voluntary Services (AWVS) with a request: the special service school—the entertainment branch of the military during WWII—had 26 men from Louisiana, he wrote, “and we would be especially pleased if we could outdo the Texas outfit in gathering things for the theatricals.” The AWVS gathered about 100 glittering satin and sequined costumes from previous Carnival dukes and maskers and sent them to the camp to be used in musical and variety shows for the men overseas.

This flag belonged to the American Women's Voluntary Services, which organized for Mardi Gras costumes to be sent to troops from Louisiana during the war. (THNOC, gift of Audrey M. Stier, 1995.33.4)

On February 22, 1944, the Mystick Krewe of Louisianians held its first ball in Washington, DC. The guests were expecting to attend a George Washington birthday party hosted by the Louisiana State Society, only to find themselves at a surprise Carnival ball. “Washington Mardi Gras,” as the annual ball has become known, continues to this day—although the 2021 event has already been canceled because of COVID-19.

But just as small informal Carnival celebrations took place in the previous war years, Mardi Gras wasn’t completely without recognition in 1945. The Mystic Krewe of Snafu, an organization composed of the Tulane University medical unit stationed in Florence, Italy, presented a Mardi Gras ball there on February 13, 1945. Entertainment for the ball consisted of skits with impersonations of Mussolini, Hitler, Hirohito, the Roosevelts, Chiang Kai-shek and his wife, Churchill, and Stalin. This was Snafu’s third year presenting a ball, after carrying out Carnival festivities at the unit’s previous posts in North Africa (1944) and Fort Benning, Georgia (1943).

After the war ended on September 2, 1945, celebrations abounded, but none were as festive as the Carnival celebration in 1946. Nearly every krewe returned, parading and masquerading in celebration of the war’s end and the return of Mardi Gras.

Korean War: 1951

This costume design was created for the Krewe of Okeanos, one of several Carnival organizations that paraded as usual in 1951, despite the war-related cancellations of the oldest krewes. (THNOC, gift of Elizabeth Y. Canik, 2017.0436.113)

Only five years had passed since the end of World War II when the US entered the Korean War. In 1951, many of the older krewes ended up canceling their presentations because of the national emergency, despite Mayor Chep Morrison assuring New Orleanians that there was no need to do so. In fact, Mayor Morrison wrote a letter to the captains of 12 krewes letting them know that the federal government did not anticipate any reduction in tourist travel. Nevertheless, Rex, Comus, Proteus, Momus, and others chose to not celebrate.

However, on Mardi Gras day, February 6, the headline on the front page of the New Orleans States read, “REVELERS TAKE OVER.” The Krewe of Hermes, the Krewe of Okeanos, and the Knights of Babylon were among those that paraded. And despite the cancellation by many of the older krewes, New Orleanians still thronged the streets. The Krewe of Patria held its first and only parade, a 20-float affair with the theme “The Freedoms.” The Krewe of Patria replaced the usual Mardi Gras Day Rex parade. Reigning as King Patria I was Lindsay A. Larson, a 25-year-old veteran of the Korean war. Captains, kings, and queens of 20 different krewes came together to form the Caputanians, which held a large ball on Lundi Gras at the Municipal Auditorium staged for white visitors and servicemen and -women.

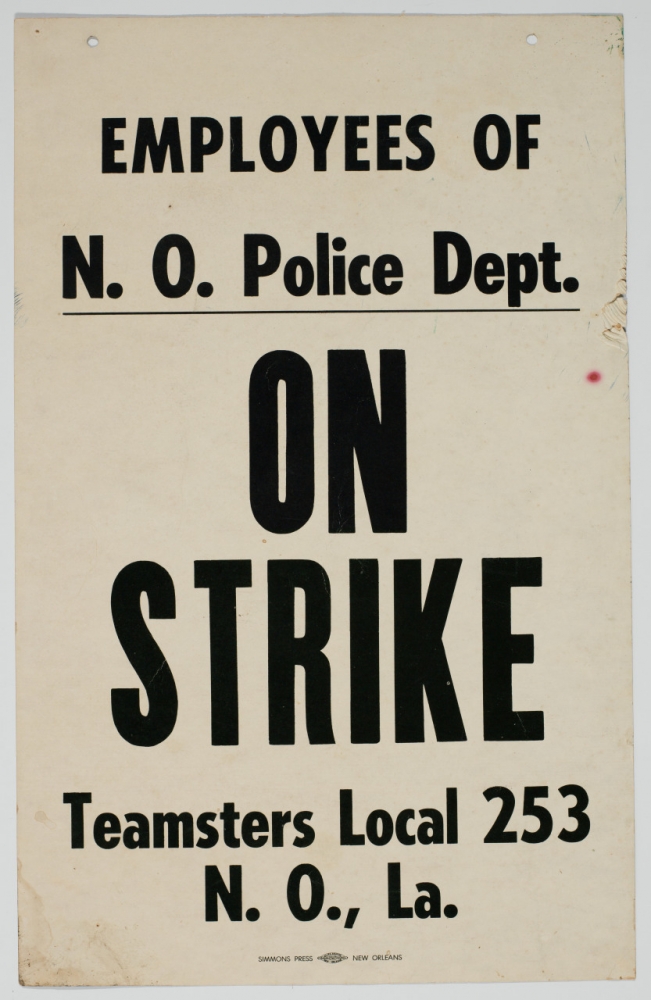

Police Union Strike: 1979

When police officers went on strike ahead of Mardi Gras 1979, some parades moved to outlying parishes, while others canceled completely. (THNOC, 2018.0522.37)

In late 1978 and early 1979, a disagreement between New Orleans Police Department (NOPD) and the city’s first Black mayor, Ernest “Dutch” Morial, resulted in a police strike during the 1979 Carnival season, which prompted the major krewes to cancel their parades or relocate to the suburbs.

The Police Association of New Orleans (PANO) was angered by the mayor’s decision to hire Birmingham police chief James C. Parsons as police superintendent, rather than promoting from within; another grievance was a pay raise that actually hurt the police more than it helped them, by taking their sick days away. PANO demanded a new salary increase, but when the mayor refused to give in, the NOPD went on strike right before Mardi Gras, bringing the parade season to a screeching halt in Orleans Parish.

In the postwar decades, Mardi Gras had begun to grow into the billion-dollar industry it remains today: “superkrewes” were introduced in the 1960s, and the city began pivoting its economy to tourism, with Mardi Gras a primary driver. As a result, the city began to rely more heavily on the NOPD to secure parade routes and manage crowds. With the NOPD on strike, several krewes canceled their parades outright, including Rex, Comus, and Zulu. Others, including Endymion, relocated to towns surrounding New Orleans—Kenner, Chalmette, Gretna, Mandeville, and Slidell.

As with years past, the shutdown of large-scale parades in Orleans Parish did not stop New Orleanians from celebrating on their own. The national guard was called in to patrol the French Quarter, but they did not attempt to disperse the crowds. People held impromptu parties in their homes and formed rag-tag parades in the streets. An editorial in the States-Item on Fat Tuesday declared it “Mardi Decharne,” or “Skinny Tuesday,” in reference to the slimmed-down celebrations.

Since then...

The 1979 police strike was the last time New Orleans has seen any significant cancellations during Carnival. Speculation flew in 1992, during the debate over the New Orleans City Council’s anti-discrimination ordinance. Introduced by Councilperson Dorothy Mae Taylor, the ordinance, which remains in place today, requires Carnival krewes to admit members without regard to race, sex, national origin, creed, sexual orientation, age, or disability. Commentators predicted the controversy would lead to the cancellation of Mardi Gras entirely, but instead, the only krewes that took issue with the ordinance were Momus, which sat the year out, and Comus, which decided to close ranks, stop parading, and only hold balls going forward.

Many thought that the 2006 Carnival season would be canceled as the city struggled to recover from Hurricane Katrina and the 2005 levee breaches, but the resilience of the city was on full display that year. Carnival was smaller than in years past, of course, but balls were held, parades rolled, and, for a moment, people could costume and dance their cares away.

On November 17, 2020, the City of New Orleans announced that no parades would roll for Mardi Gras 2021, due to the COVID-19 pandemic that has claimed more than 247,000 lives around the US. However, if the history of canceled Carnival has shown us anything, it’s that Mardi Gras is more than just big parades and fancy balls. Mardi Gras can’t be canceled any more than Christmas or New Year. It might decrease dramatically in scale, but the people of New Orleans will always find a way to celebrate—safely.

Correction: This story has been updated to reflect the correct number of times that Carnival parades have been cancelled (14).