With the global outbreak of coronavirus, we find ourselves in the middle of a world-altering event. Here in New Orleans, which has one of the highest concentrations of COVID-19 cases in the country, we are adjusting to this new reality of life during a pandemic.

For all of us at The Historic New Orleans Collection, these historic times compel us to extend our work in new ways: while we will continue to present history, we are also chronicling it in real time.

THNOC is actively collecting material related to the COVID-19 pandemic as it unfolds, and staff are exploring new ways to capture public reaction to the crisis so that future generations can understand it.

How we're collecting

Café du Monde is shown closed down, a rare sight for a 24-hour establishment in the heart of the French Quarter. On March 16, 2020, Governor John Bel Edwards ordered all restaurants to serve take-out customers only. (Image courtesy of Dmitriy Pritykin).

Primary sources are crucial to our understanding of history. And for decades, THNOC has actively collected primary source materials relating to upheavals in our society, from the Civil War and yellow fever outbreaks of the 19th century to the civil rights movements of the 20th. For the benefit of researchers, we have gathered letters, journals, objects, media, and other ephemera generated in the course of human events—the raw materials from which history is made.

“Primary sources give us unique insight into who the people were living at the time and the world going on around them,” said Associate Curator Aimee Everrett. “For instance, we can read about the events that unfolded during a battle, but a letter or diary gives us the first-person experience of what it was like to fight.”

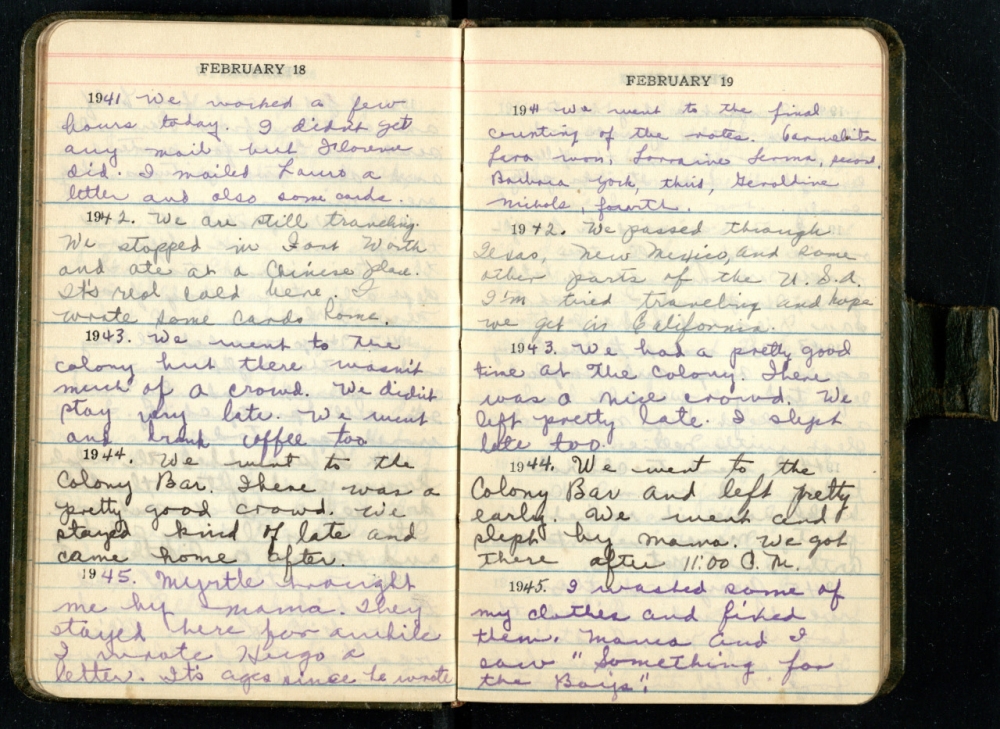

A diary page from Celine Hidalgo records her daily activities. Journals and letters give researchers a first-person perspective on history. (THNOC, 2018.0060.1)

To collect manuscripts during the 21st century, THNOC has had to adapt its practices; people rarely record their thoughts on paper anymore.

“Think about the last time you wrote a physical letter versus, say, an email,” said Everrett. “So much is born digitally. For years, we as curators have been harvesting emails and copying content from CD-ROMs or floppy discs. Online content is just the next medium.”

A couple of recent news events that generated significant online chatter—the Confederate monuments debate and the street flooding of August 2017—prompted Everrett and colleagues to develop a process for collecting social media reactions and online coverage.

In 2018 THNOC decided to use a program called Archive-It to preserve online news sources, city updates, and social media conversations about historic events in New Orleans. The software “crawls” a website, meaning that it copies the look and content of a page and saves it as a file that can be accessed later. This way, someone in the future can view an article, tweet, or update just as it looked when it was posted.

“Our communications and interactions are taking place in a new realm,” said Everrett. “If we aren’t capturing the material in a new format, it will be lost.”

THNOC’s digital-content harvesting started with a test collection that gathered web pages and social media posts during the first 100 days of Mayor LaToya Cantrell’s administration. Collected data included crawls of the city’s website, news articles, and certain hashtags surrounding the new administration.

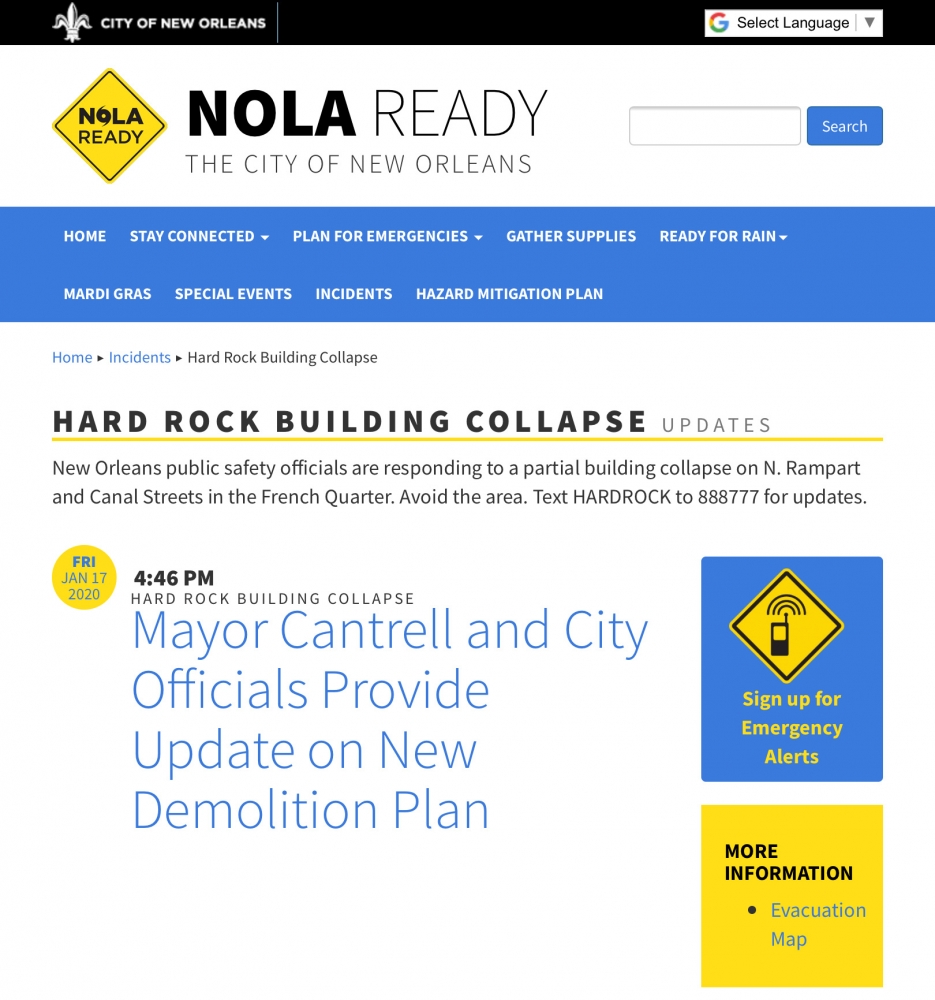

The most concerted effort thus far, however, has been in capturing the response to the Hard Rock Hotel collapse. Everrett directed THNOC’s software to crawl Nola.com articles; websites, including that of Congress of Day Laborers/Congreso de Jornaleros; and tweets including hashtags like #hardrockcollapse. One day, all of those materials will be available to researchers through a searchable online platform.

A screenshot of a NOLA Ready webpage shows official notices about the city’s demolition plans for the collapsed Hard Rock Hotel.

But collecting doesn’t stop there. While the content found on the web is helpful, Everrett is eager to collect physical objects related to the collapse. She and other staff members have gathered signs from protests, a decal ordering a Canal Street business to remain closed, and posters for workers’ advocacy groups.

Together, the digital and physical collections will work together to present a clearer picture of the response to the disaster and its effects on the city.

The spread of COVID-19 has taken this effort to a whole new level.

The door of d.b.a. is plastered with a hopeful message, stressing the importance of social distancing measures. (Image courtesy of Dmitriy Pritykin)

As we’ve seen over the past two weeks, bars, shops, and restaurants have shuttered or altered their businesses to adapt to strict social distancing guidelines. Layoffs are starting to hit the city’s tourism industry, and the city’s economic future is blurry. Festivals have been canceled or postponed. At time of publication, 1,795 Louisianans have tested positive for the virus, scores more are infected without knowing, because of the country’s slow response to testing, and 65 have died in the state.

“We’re crawling pages like the NOLA Ready website and the Nola.com article that is updated with the number of cases in the state and where they’re located,” said Everrett. “But we’re also capturing individuals’ reactions through Twitter hashtags like #nolaopen, #coronavirus, and #COVID19, all centered upon our local area.”

In the midst of the uncertainty, THNOC is sticking to its mission to preserve and present the history of the city and region. While these articles and posts could be lost or deleted by their creators, they will be preserved as digital files that researchers can access years from now to understand how this pandemic unfolded in New Orleans.

We need YOU—to be a primary source

THNOC Reference Associate Robert Ticknor posted an image of his work-from-home setup. We’re asking people all over the city to share their daily lives with #nolacorona.

In September 1833 Carl Kohn penned a letter about the state of the Yellow Fever outbreak in New Orleans wherein he wrote that “a quiet and tranquility reign over the town, which is only disturbed by the occasional rumbles of the mourning vehicles—no sort of business is going on, scarcely is anybody to be met with in the streets...all strangers there, that have not yet had the fever, expect its attack with as much certainty, as a condemned criminal does expect the sentence of his execution.”

Between the quiet streets and sense of looming dread, this primary source remains relevant today. And now, almost 200 years later, we have been tasked to write a chapter at this moment in New Orleans’s history.

How are you spending these days? How are you recording the details of your interrupted life? Share those details here with us.

Our Archive-It web crawler will be saving public tweets using #nolacorona, making your contribution automatically a part of our collection.

A snapshot of a journal entry. An email to mom. Group text threads. An inventory of all the toys on the floor. An account of your trip to the grocery store. Your symptoms. Your remedies. The places and people you miss. We’re at home, too. Tell us your story using #nolacorona.

What we would like from New Orleans

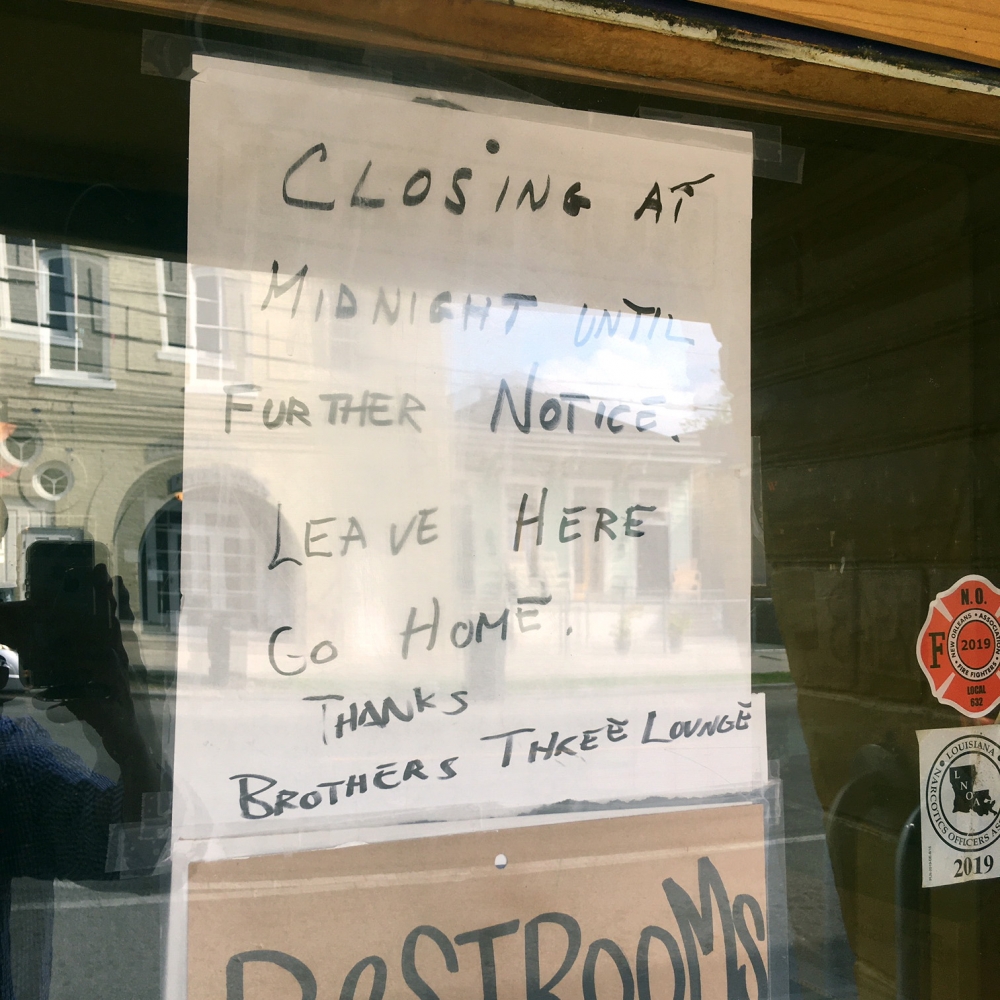

A sign on the door at Brothers Three Lounge alerts customers of the bar’s closure, telling them to go home. (Image courtesy of Dave Walker)

When it is safe to do so, our curatorial team will be actively seeking ephemera—such as signage from restaurants, shops, and grocery stores—that was used during this crisis. No matter what it’s made of and no matter what the message is, ephemera will supplement social media posts and provide tangible context for future generations of researchers. For example, a tweet lamenting the lack of bottled water at the supermarket could be corroborated by a sign intended to limit the sale of bottled water.

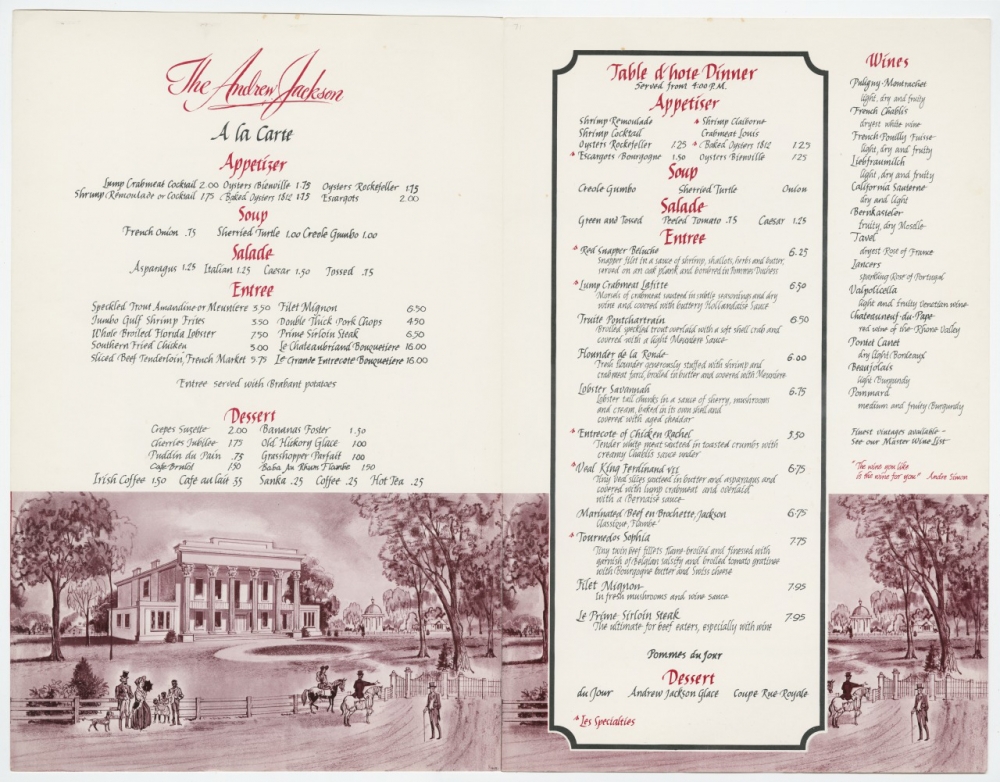

A circa 1975 menu from the Andrew Jackson Restaurant is one of many from THNOC's holdings. We are now asking for digital files of restaurant menus that have been altered due to social distancing guidelines. (THNOC, 2008.0226.2)

THNOC is also looking to expand its long-standing collection of restaurant menus from around New Orleans, some dating back to the 19th century. We ask restaurant owners or managers to send us digital files of special menus that have been created due to social distancing measures. These menus will expand our collection and show how local restaurants adapted to the crisis. Please email files to firstdraft@hnoc.org.