Editor’s note: This story is released in conjunction with The Historic New Orleans Collection’s 2021 Symposium, “Recovered Voices: Black Activism in New Orleans from Reconstruction to the Present Day” and the publication of the book Afro-Creole Poetry in French.

On Wednesday, October 14, 2020, The Historic New Orleans Collection published a remarkable new volume: Afro-Creole Poetry in French from Louisiana's Radical Civil War–Era Newspapers. Collected and translated in full for the first time, 79 original works by over a dozen activist authors resurrect powerful voices from the foundational era of the civil rights struggle—which began not in the 1950s and ’60s but in 1860s New Orleans, in French. To understand the significance of these poems, and the poets, we spoke with author Clint Bruce.

Below, he answers six questions that illustrate the literary value of these works, the history behind their publication, and how they relate to our current day.

1. Many of these poems relate to Black activism. How do these works ring true today, and how are they different?

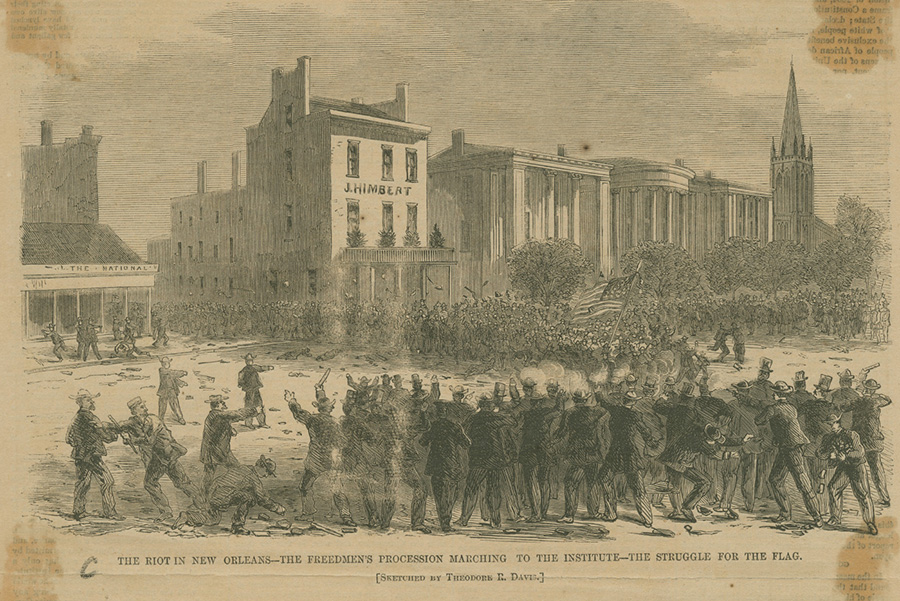

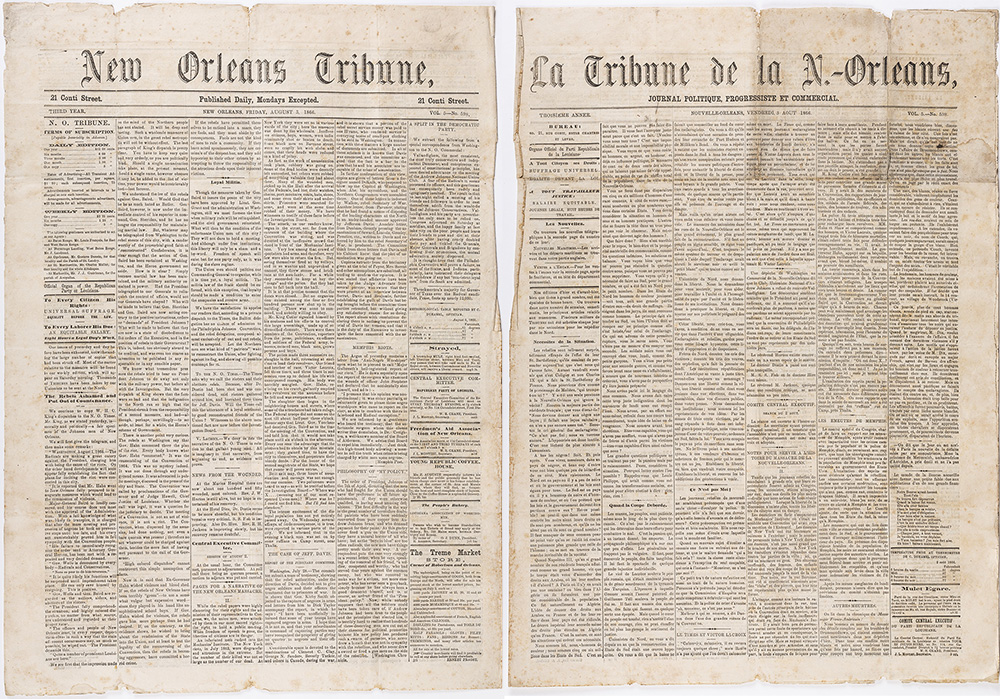

A newspaper sketch depicts the 1866 Mechanics’ Institute massacre in New Orleans—in which white crowds, including police and firemen, killed peaceful protesters marching in support of Black suffrage. (THNOC, 1974.25.9.308 i)

A newspaper sketch depicts the 1866 Mechanics’ Institute massacre in New Orleans—in which white crowds, including police and firemen, killed peaceful protesters marching in support of Black suffrage. (THNOC, 1974.25.9.308 i)

The current struggle in the US for fair treatment of Black people, which extends from the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s, has roots a century earlier, during the Civil War and Reconstruction. Because most of these 19th-century poems were written in a relatively straightforward tone and don’t sound particularly old-fashioned, many parallels between then and now will jump out at readers, even people not used to reading poetry.

One common thread is the poetry’s emphasis on voting rights. In the 1860s, activists struggled hard to ratify the 14th Amendment and to defeat laws designed to disqualify Black voters. The struggle to guarantee the right to vote for all Americans has continued to the current day. The fact that Black people in the 21st century still have to fight to claim their right to vote is infuriating.

A poem about the 1866 Mechanics’ Institute massacre in New Orleans—in which white crowds, including police and firemen, killed peaceful protesters marching in support of Black suffrage—becomes almost chilling when read in the context of today's Black Lives Matter movement:

Policemen and firemen, come! Does calm arise?

No! For atrocities, they win the prize.

. . . . . .

Says he, “By spilling this blood, we’ll save our country!”

And, by God, they killed their share!

(from “Ode to the Martyrs” [1867], by Camille Naudin [pseudonym])

Like the protestors today, the poets call attention the racism built into our social systems. The poem “To Father Chocarne,” for example, denounces segregation in the Catholic Church. The challenges of coalition-building, both cross-racially and over other divides (such as social class), will also be familiar to 21st-century activists.

In other ways, the poems are firmly anchored in their time. Even though women played a vital role in the activism of the Creole community, several of the texts tend to impose a traditionalist view of sex and gender roles. This conservatism will be frustrating for many readers. Also, readers won’t always share the idealism of the poets’ worldview, moored as it is in the Romantic age. The radicalism expressed in the poems, however, will seem very relevant to our own times.

2. Who are these poets—how did they earn a living? Why were they writing in French?

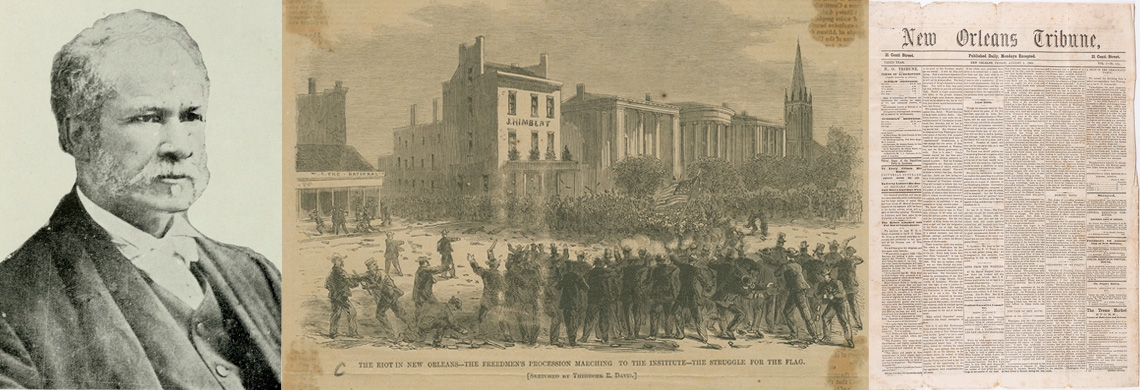

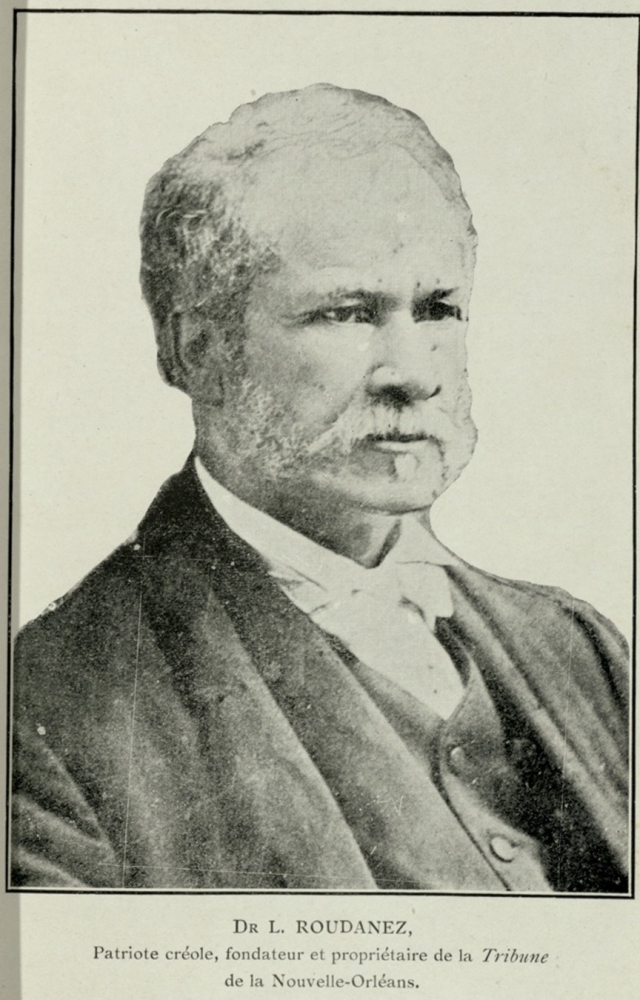

Louis Charles Roudanez was one of the founders of the New Orleans Tribune and L'Union, the newspapers in which the poems were originally published. (THNOC, 69-201-LP.5)

Louis Charles Roudanez was one of the founders of the New Orleans Tribune and L'Union, the newspapers in which the poems were originally published. (THNOC, 69-201-LP.5)

New Orleans’s community of French-speaking free people of color (gens de couleur libre) dates from the early 18th century. French and Spanish governments were more accepting of interracial relationships and manumission, so by the time Louisiana joined the United States, New Orleans and several other areas had populations of educated, influential French-speaking Afro-Creoles.

Simply put, these poets wrote in French because French was their language—not only their mother tongue (though some of them likely spoke Louisiana Creole first), but also, most importantly, the language of their education and worldview.

French in Louisiana was not a foreign language: in the 19th century, it was the dominant language of the arts, the sciences, and world affairs. These Creole poets were not merely imitating Europeans, as has sometimes been claimed—at least, not more than any aspiring author emulates the great masters while finding their own voice.

These poets were prominent citizens who made their living as authors, artists, performers, tradesmen, and entrepreneurs, among other professions. Several were teachers. One was a cigar-maker.

3. Why should we read these activists’ poetry? Is it different from the journalism and speeches and other things they wrote? Why did they publish their poetry in the newspaper and not in literary journals or books?

The building at 527 Conti Street, shown here, housed the original offices for La Tribune. The Historic New Orleans Collection's Conti Street Annex is right next door. (Image courtesy of the Vieux Carré Survey.)

Newspapers of the 19th century regularly featured poetry, short stories, and serial novels. Nothing special there. The newspapers that published these particular poems, however, were quite special. L’Union (founded in 1862) and La Tribune de la Nouvelle-Orléans (founded in 1864, just after L’Union folded) contributed mightily to the civil rights struggle of the 1860s.

Interestingly enough, La Tribune became the United States’s first Black daily newspaper—a bilingual one, to boot. Both papers fought for the freedom, equality, and dignity of African-descended people in the United States. W. E. B. Du Bois, the famous sociologist and pioneer of African American studies, remarked that La Tribune served as “an unusually effective organ for the Negroes” of Louisiana and the nation. Both are crucial in the history of Black America and the French-speaking world.

Using poetry (as opposed to editorials and other prose) to tackle social injustice and other weighty topics allowed these Creole writers to demonstrate their mastery of language, of aesthetic form and literary codes—and in so doing, prove their intellectual worth to those who doubted it.

Many of the poems make for inspiring and enjoyable reading today. They also provide a unique and important window on the worldview and values of these francophone civil rights activists: in general, the tone of the poetry shows the writers to be more idealistic and egalitarian than this elite class sometimes gets credit for.

4. You spent ten years translating these poems and unearthing new information about their lives and about the newspapers. What were your biggest surprises?

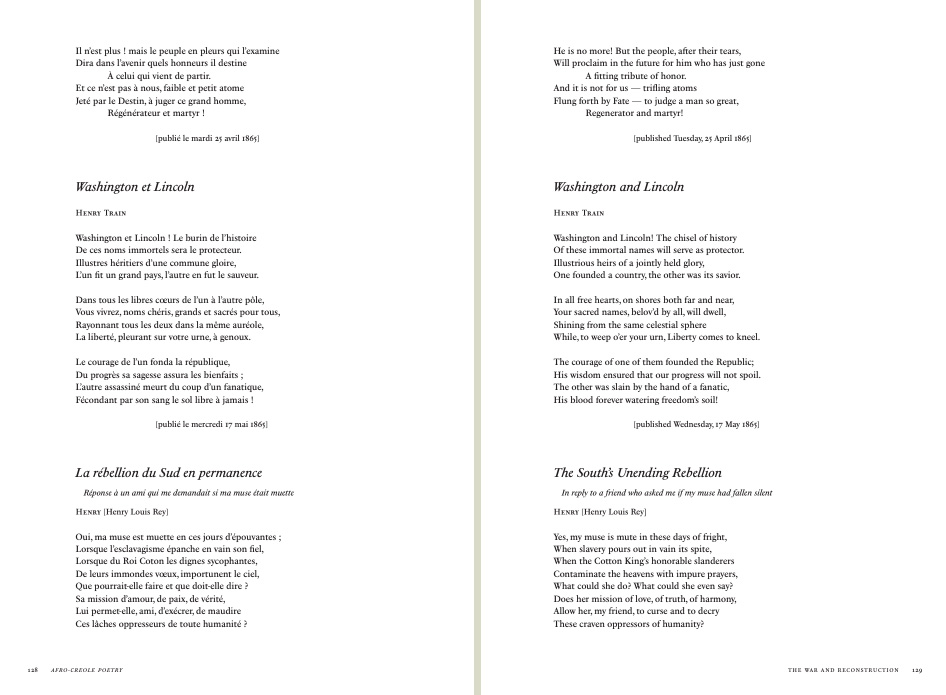

French and English covers of La Tribune from August 3, 1866 are shown side-by-side. The issues, which covered the aftermath of the Mechanics Institute massacre, were presumed lost until rediscovered by Bruce in research for this book. (Images courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society.)

This journey has been filled with discoveries, some whose full significance I am still processing, to be honest. As readers will discover in the introduction, the Creole composer, actor, and political activist Victor Eugène Macarty committed a literary hoax by publishing under the pseudonym “Antony” five poems recopied from French literary magazines. A tip from scholar Bill Horne about one poem put me on the trail, and eventually I discovered that the other four “Antony” poems were also hoaxes.

I figured this deception out late in the game, only a few months before going to press. And I panicked! A lauded figure had “plagiarized”! Nevertheless, this hoax, which I suspect other members of his circle knew about, detracts neither from his real contributions in other domains, nor from the original writings of the other poets. The hoax poems are forever woven into the poetic conversation: the “Antony” poem “He Is,” for example, prompted Armand Lanusse to write the poem “He Is Not.”

Highlighted in my preface, the surprise of uncovering the reportedly lost issues of La Tribune from the days following the Mechanics’ Institute massacre of July 30, 1866, both awed and humbled me. Countering narratives about Black “rioters” described in white-run presses, La Tribune reports of the people marching in support of Black rights, “For a while [the protestors] succeeded to keep at bay the ‘thugs’ and the police. But they had soon to fall back into the hall. . . . The police made three successive onslaughts in the hall, retreating at each time to load their revolvers” (August 3, 1866).

Though not quite a surprise, it is astounding how much time and painstaking effort can go into translating a poem! By my estimate, a given sonnet—comprising 14 lines, of course—usually took me eight to ten hours, often over several sessions.

5. You organized the poems by theme, not by poet. Why? What are some different ways for readers to approach the book?

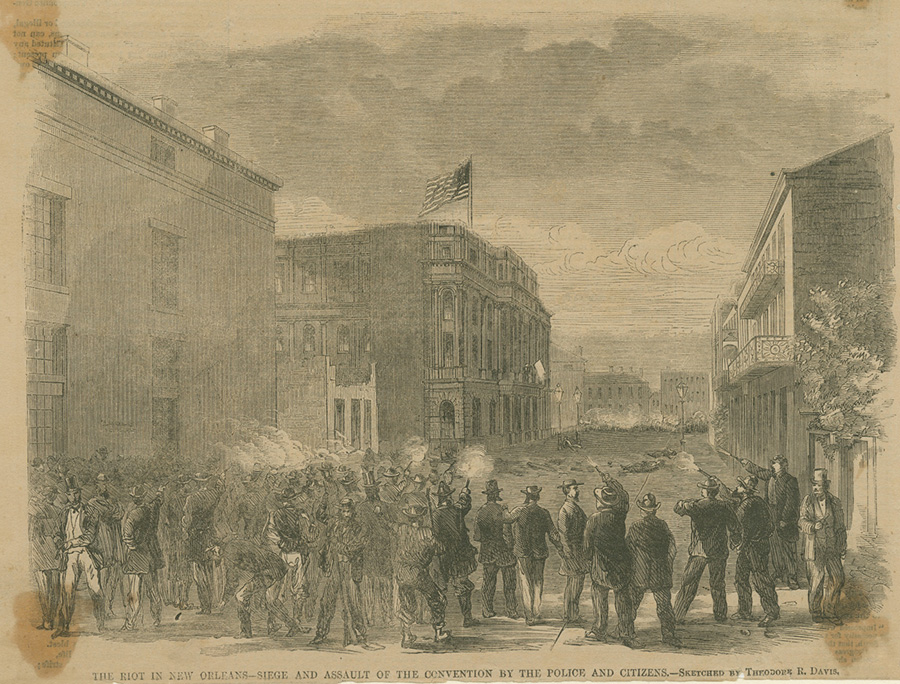

Inside the book, the original French poems run opposite their English translations. Bruce translated each poem that went into the volume.

The poems are divided into five thematic sections, in chronological order within each section. I wanted to highlight the poetry’s engagement with culture, politics, and philosophy. I also wanted to reveal the direct conversations woven into the poetry: many of these poems were written in response to each other, and 19th-century readers could follow the dialogue from issue to issue. In short, I want the poetry to pack a punch for today’s audience, as it did for its original audience.

My introduction, notes, and short biographies of the poets are designed to be enjoyable and accessible for anybody, whether or not you know anything about 19th-century New Orleans or poetry or free people of color or the history of Civil Rights. I have supplied plenty of explanations, so that reading even just one poem will open up doors to understanding these Creole writers and their world.

I also want readers to understand that these writers weren’t just addressing current events: their verses also reflect an active examination of the very function of poetry in their society. They asked questions writers still ask today: How can literature inspire a vision for a just world and a renewed nation? How can literary creation sustain the activists fighting for that vision?

The first section, “Poetry as Prophecy,” foregrounds this role. The next two sections (“The War and Reconstruction” and “Liberty, Racial Equality, and Fraternity”) bring us more concretely into the struggles of early Reconstruction, and the last two feature philosophical and sentimental verse.

The sheer number of sentimental and romantic poems weighed heavily in my choice to organize the volume by theme. Had I simply arranged everything chronologically, they would have drowned out the political and social poems. None of the poems here, after all, was originally intended to be collected in a book. Once the poetry is removed from the context of the newspapers, its arrangement should take other concerns into account, for today’s readership.

6. What is the most important thing you hope readers take away from the volume?

Another sketch of the confrontation at the Mechanics' Institute labels the conflict a "riot." La Tribune described demonstrators marching for Black rights. (THNOC, 1974.25.9.308 ii)

These poems have not finished their work. They have not stopped speaking, and we have much to learn from these voices from 150 years ago. To me, they are much like 19th-century Spiritualist communications: messages of encouragement, enlightenment, and spiritual succor that members of the Spiritualist religious movement—including several of these poets—believed were sent from the afterlife by historical figures or deceased family members, to inspire and aid those on earth still struggling forward. Many of us who care about issues of racial and social equity, and of societal healing as well, need to believe these lines by Adophe Duhart:

It shall not be said that, born of the storm, our age

Will never be able to feel upon its visage

The sunlight of Equality.

(from “Stanza” [1865])

Although the book’s introduction and notes focus on the social and cultural conditions of these poets, our respect for their struggle should not limit the scope of our own. Their Reconstruction-era world was undergoing earth-shifting transformations, and so is ours. I believe they would want us to tackle the challenges of our time on our own terms, even as we draw from their example.

For more, explore THNOC's new book Afro-Creole Poetry in French.