New Orleans culture has long been characterized by its French and Spanish colonial history and its Black history, but its global connections and ethnic diversity go far beyond Europe, Africa, and the Caribbean.

Much of the material culture preserved by The Historic New Orleans Collection—artifacts, architecture, art, written material, and other physical objects—brims with information about the varied roles of immigrant populations in shaping the city’s economy and culture. “Coming to New Orleans” is a new series, presented in conjunction with American Democracy: A Great Leap of Faith, that tells stories of New Orleans immigration history through different items in our holdings. Future parts in the series will explore different immigrant groups and time periods in more depth. But first, an overview: let’s look at New Orleans immigration in the context of American immigration, with this timeline.

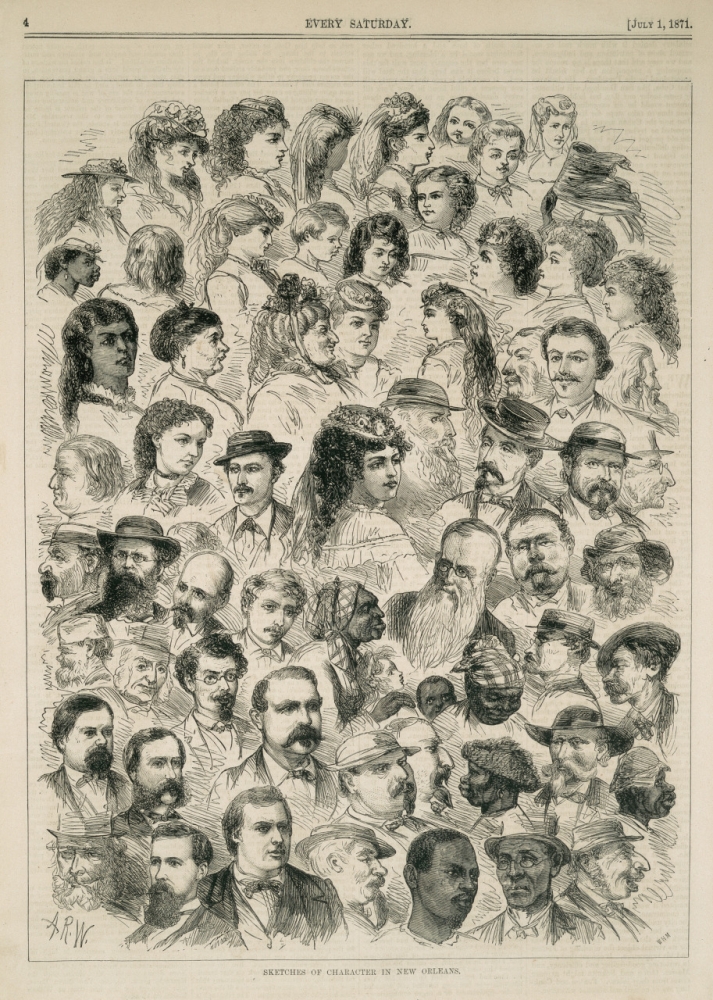

This 1871 magazine illustration by Alfred Rudolph Waud, titled Sketches of Character in New Orleans, shows some of the different types of people living in the city at the time, including a variety of racial and ethnic identities. (THNOC, gift of Boyd Cruise and Harold Schilke, 1953.87)

Colonization and Enslavement, 1718–1803

Indigenous groups were the first people to reside in what would be called New Orleans. The Chickasaw, Chitimacha, Choctaw, and many other Indigenous tribes had lived in and regularly traveled to the area to trade with each other before the French established New Orleans as a new colonial captial for Louisiana in 1722. Throughout the French colonial period, voluntary migration from France was slow. The forced migration of Africans and the forced removal of Indigenous people account for the only major population fluctuations within the city limits during this time. Beginning in 1721, the Company of the Indies removed Africans, mostly from the Senegambian region, to work in Louisiana under a cruel system of racial slavery. Though the French cooperated with and relied on the Indigenous tribes of South Louisiana, many Native Americans were captured and enslaved, both in Louisiana and in the more profitable French colony of Saint-Domingue.

The Spanish, who took over from the French in 1762, saw immigration as a way to establish control over the area, which they governed from Havana. The crown provided land grants to settlers, many from the Canary Islands and other parts of the Hispanic world. Though immigration increased during the Spanish colonial era, it wasn’t until Louisiana became an American territory, and later an American state, that migrants began to arrive from all around the world and leave their mark on New Orleans.

Americanization and Growth, 1803–1862

The six decades between the Louisiana Purchase and the capture of New Orleans during the Civil War was a time of aggressive westward expansion in the young country of the United States.

At the time of the Louisiana Purchase, French-speaking Catholics had been the majority population in the small city, but once the European colony became an American state, Anglo settlers began to arrive in New Orleans in large numbers, disrupting the existing social order. In the 1850s, the city expanded its boundaries upriver, allowing for more settlement for the growing English- and German-speaking populations. Recently arrived immigrants often lived and worked in crowded conditions, making them particularly vulnerable to the deadly yellow fever that swept through the city continuously throughout this period.

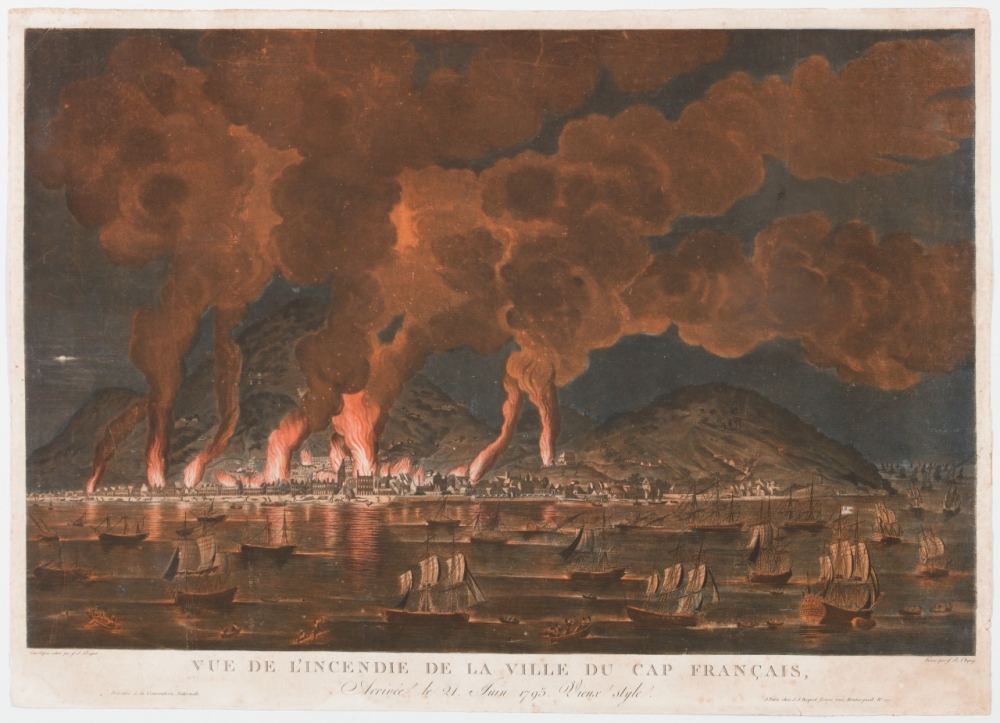

This engraving of an oil painting depicts the burning of the city of Cap Francais, one of the most destructive events of the slave uprising in Saint-Domingue, which came to be known as the Haitian Revolution. The uprising was watched closely in Louisiana, where white enslavers feared a similar uprising among the enslaved population. (THNOC, 2016.0219.1)

In the 30 years leading up to the Civil War, the Port of New Orleans was second only to New York City in the number of international arrivals. The Haitian Revolution, which had begun in 1791, caused those opposing the revolution to flee, including white enslavers, free people of color, and enslaved people. In 1810 a wave of these Haitian refugees came to New Orleans from Cuba, more than doubling its enslaved population and nearly tripling its population of free people of color in a matter of months. Political revolutions and famines in Europe brought a large wave of Irish and German immigrants to New Orleans from the 1830s to the 1850s. During the same time Central European Jews arrived, seeking religious freedom guaranteed by the Constitution. In the 1850s, New Orleans became a staging area for filibustering campaigns as Cuba sought its independence from Spain, leading to increased immigration and political ties with Cuba.

The mid-19th-century period of US expansion was driven by the doctrine of manifest destiny, which worked in concert with the racist pseudosciences of phrenology and eugenics. These beliefs of white Western superiority and predestination, purportedly backed by science, informed many citizens’ and lawmakers’ perceptions of foreign countries and nonwhite races. When Louisiana became a state in 1812, the only federal law in place regarding immigration was the 1790 Naturalization Act, which defined American citizenship as belonging only to descendants of white Europeans. The federal government didn’t even start keeping immigration records until 1820 and wouldn’t pass any restrictive immigration laws until the late 1880s.

Progressivism and Chinese Exclusion, 1863–1917

The period from Reconstruction to World War I was a time of political violence and increased debate over the dangers of immigration throughout the US. The 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act grew out of racial tensions between Asian immigrants and whites in California in the 1870s. It was the first and only law in US history to bar a specific ethnic group from entry into the country, and it created the nation's first framework for immigration enforcement and bureaucratic structure.

Though international immigration from China was restricted by the federal government, Chinese immigrants from California could and did come to Louisiana during this period. Along with Filipinos, who had been in Louisiana since the Spanish colonial era, these Asian immigrants dominated the Gulf Coast dried-shrimp industry in the final decades of the 19th century.

Also key to the economy was the Italian community: while Italians had been immigrating to New Orleans since the 1830s, the arrival in the 1880s of a massive migration wave from Sicily dramatically increased their visibility and influence. Though initially discriminated against, Sicilian immigrants became a strong merchant class who contributed to the marked Italian character of the lower French Quarter. Eastern European Ashkenazi Jewish immigrants also arrived during this period, adding to the ethnic diversity of the city’s existing Jewish population.

This page from an early 20th-century scrapbook shows the immigration-processing buildings in Algiers Point in 1916, where newly arrived immigrants to New Orleans would have been screened and cleared for entry into the city. (THNOC, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Peter Bernard, 1984.112.228)

World War I, which began in 1914, increased national anxieties about immigration from Asia and southern and eastern Europe and slowed the influx from both regions. The city’s population, however, more than doubled in the early decades of the 20th century, with the arrival of newly emancipated Black Americans during the movement called the Great Migration. While large numbers of Black southerners moved north of the Mason-Dixon line, many of those who remained relocated from small towns and rural areas to major cities like New Orleans in search of better economic opportunities.

The Quota System and the Red Scare, 1918–1964

After the First World War, the United States government passed the most restrictive immigration law in the nation’s history. The Immigration Act of 1924, also called the Johnson-Reed Act, instituted a quota system based on nation of origin, which capped the allowed number of new immigrants from a country according to how many people from that country had been listed as living in the US in the 1890 census. The 1924 law greatly favored the western and northern European countries whose immigrants had already arrived in large numbers in the 19th century, while severely limiting or even cutting off immigration from southern and eastern Europe and Asia.

In the years during and following World War II, the US government eased restrictions for refugees and asylum seekers and granted entry beyond the quota system on an ad-hoc basis. Anti-Communist hysteria at the start of the Cold War, however, increased scrutiny on immigrants, resulting in the lowest immigration numbers ever during the 1950s and ’60s. The relationship between the United States and Mexico soured during this period: a federal initiative called the Bracero Program had brought Mexican workers to the US to help the nation with its wartime labor shortage, but after the war many of these workers were sent back to Mexico in mass deportations.

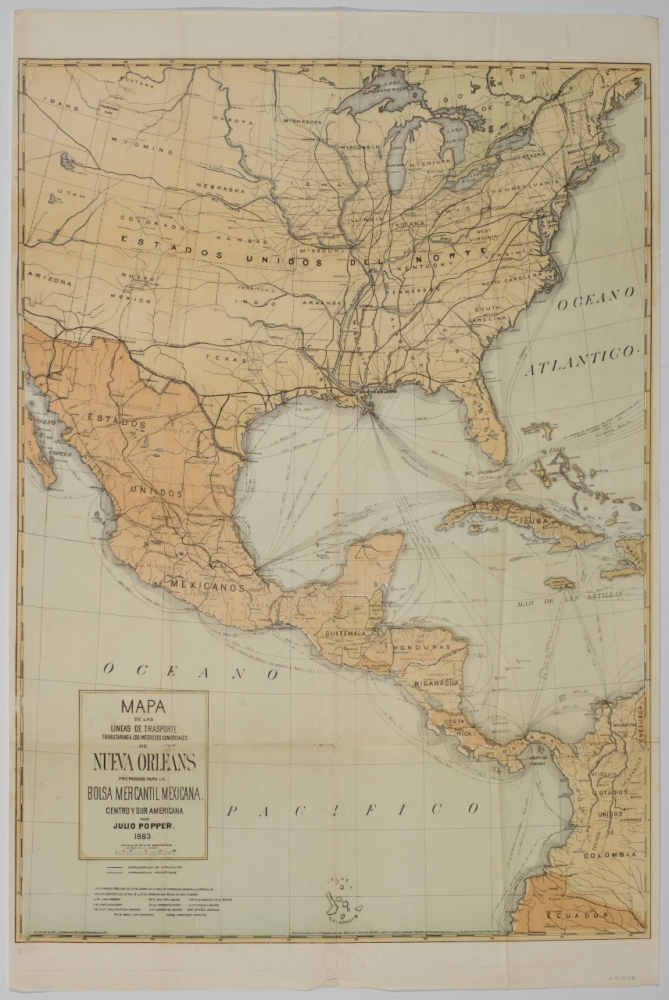

This 1883 map shows ship and rail lines for cargo and transportation among the United States and Central and South America, demonstrating the importance of New Orleans to greater Latin America as a major shipping hub in the 19th century. (THNOC, 2018.0021)

During this period immigration to New Orleans reflected the overall US decline, but there was a local influx of ethnically and racially diverse Latinos from Central America and the Caribbean. Some anti-communist Cubans arrived in the city after Fidel Castro came to power in 1959, but not nearly as many as went to Miami. Since the 1890s the banana trade had made New Orleans the gateway city for Hondurans traveling to the United States. Many settled here because of the Catholic culture, warm and humid climate, employment opportunities, and growing expatriate community. Honduran migration began in the early 20th century, but the largest group came in the 1950s and ’60s. By 1962, New Orleans had the world’s largest population of Hondurans outside of Honduras itself. From the Middle East, French-speaking Christian Lebanese immigrants had been coming to Louisiana since the 1880s; after the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, they were joined by Arabic-speaking Muslims from several countries.

Civil Rights and Reform, 1965–2005

In 1965 Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Immigration and Nationality Act, which repealed the 1924 immigration-quotas law. The new bill was not without shortcomings, as it introduced a Western-hemisphere immigration cap designed to exclude Mexicans and Central Americans. The decades that followed saw an unprecedented migration wave from Asia, Africa, and Latin America that would drastically reshape the demographics of the country, especially in the South. The demonization of "illegal aliens" entered public rhetoric when President Clinton signed the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IRIRA) into law in 1996. Fear of immigrants grew following 9/11, leading to increased scrutiny on immigrants and the foundation of the Department of Homeland Security in 2002, with border security as one of its main functions.

Beginning in the 1960s, the New Orleans population began to decline because of economic recession, white flight, and suburbanization. While the economy boomed in the 1970s with the growth of the petrochemical industry, the oil bust of the 1980s led to economic stagnation throughout the 1990s. In 2005, Hurricane Katrina dispersed populations and changed the landscape as well as the racial and ethnic makeup of the city. Some 75,000 Black residents were displaced outside of the city, and over the following decade gentrification brought more affluent white residents into traditionally Black neighborhoods.

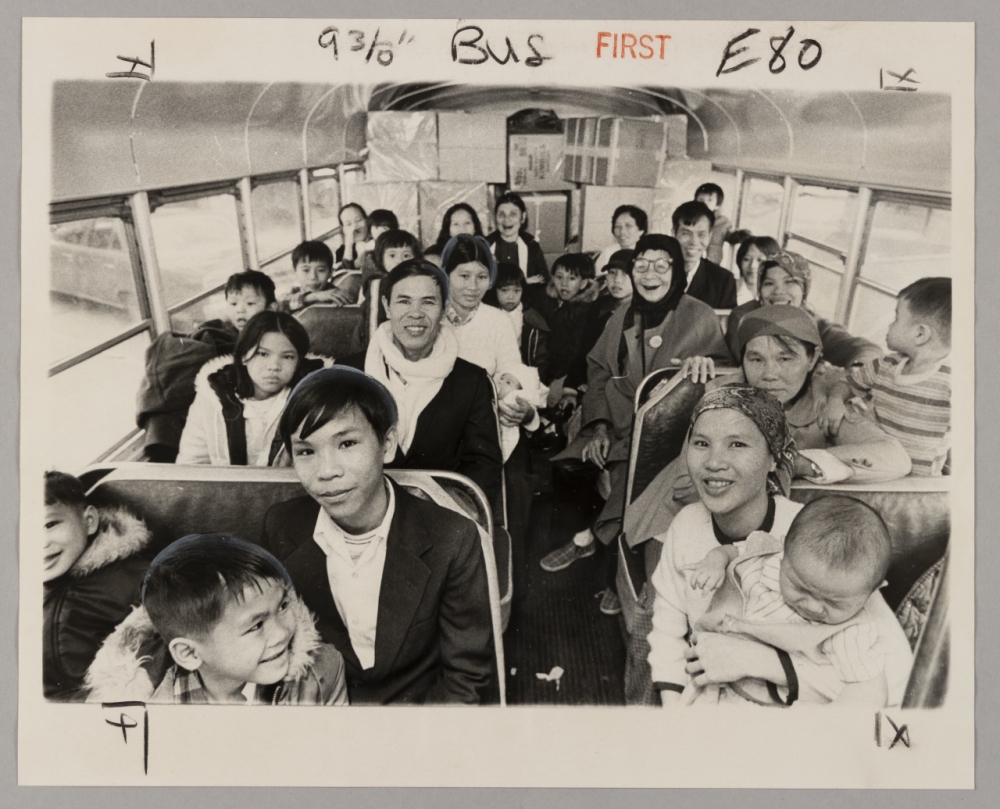

This press photograph from December 1975 depicts newly arrived Vietnamese refugees on a bus traveling from Arkansas to the New Orleans area, where they were welcomed by the Catholic community in New Orleans after the fall of Saigon. (THNOC, gift of Mark Cave, 2021.0175)

Immigrants to New Orleans in the late 20th century came from the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and Latin America. Palestinians and Syrians displaced after the Six Day War in 1967 arrived in New Orleans, settling largely in Metairie and New Orleans East. After the fall of Saigon in 1975, Archbishop Philip Hannan welcomed Catholic Vietnamese refugees, who built a lasting community in New Orleans East and on the West Bank. Though Mexicans, including political exiles and wealthy businessmen, had been coming to New Orleans since the 19th century, their population doubled after Hurricane Katrina, when many workers came from Texas to assist in the rebuilding efforts. These Mexican immigrants mostly settled on the eastern and southern edges of the city, as well as in Kenner, where their numbers almost matched the existing Honduran community, replacing Cubans as the second-most populous group of Latino immigrants.

New Orleans’s industry and culture have been shaped by immigrants throughout the city’s existence. The most recent Louisiana Constitution (1974) includes a clause introduced by the Council for the Development of French in Louisiana (CODOFIL), and while originally designed to preserve the French language in Louisiana, it nevertheless reflects the multicultural quality of the state, ensuring the “right of the people to preserve, foster, and promote their respective historic linguistic and cultural origins.”

Coming to New Orleans

Explore other parts of the series:

- Five Items that Tell the Story of Immigration Between the Louisiana Purchase and the Civil War

- Six Items that Tell the Story of Immigration Between the Civil War and World War I

- Four Items that Tell the Story of Immigration Between World War I and the Civil Rights Act

- Seven Items that Tell the Story of Immigration Between the Civil Rights Act and Hurricane Katrina