The “Coming to New Orleans” series, presented in conjunction with American Democracy: A Great Leap of Faith, tells stories of New Orleans immigration history through items in our holdings. Read the first part of the series, a timeline that looks at New Orleans immigration in the context of immigration to the US, here.

Immigration to New Orleans between 1965 and 2005 was precipitated by two disasters: the fall of Saigon and Hurricane Katrina. In one case, New Orleans welcomed refugees from war-ravaged Vietnam, and in the other, Mexican immigrants came to help New Orleans rebuild and recover from devastating flood damage. In 1965, President Johnson signed the Immigration and Nationality Act into law, which abolished the quota system that had been in place since 1924 but introduced a cap on Western Hemisphere immigration that made it more difficult for Hispanics and Latinos to obtain asylum and legal citizenship. Meanwhile, civil rights legislation and an economic boom in the 1970s and early 1980s made New Orleans a more attractive place for non-white people to settle, including immigrants and those migrating within the US. After 1970, New Orleans was no longer a white majority city, and after 2005, when the Mexican population nearly doubled, the city joined the “New Latino South.”

Vietnamese Immigrants

At the end of the Vietnam War, the United States government assisted with the evacuation of over 100,000 refugees from South Vietnam. These refugees included women, children, and families of soldiers in the South Vietnamese army, who were subject to oppression and imprisonment by the North Vietnamese communist forces. After 20 years of war, many of these people were desperate to leave, and faced difficult and harrowing journeys to reach the United States. Upon their arrival, they were brought to refugee camps to receive assistance, including Fort Chaffe in Northwest Arkansas.

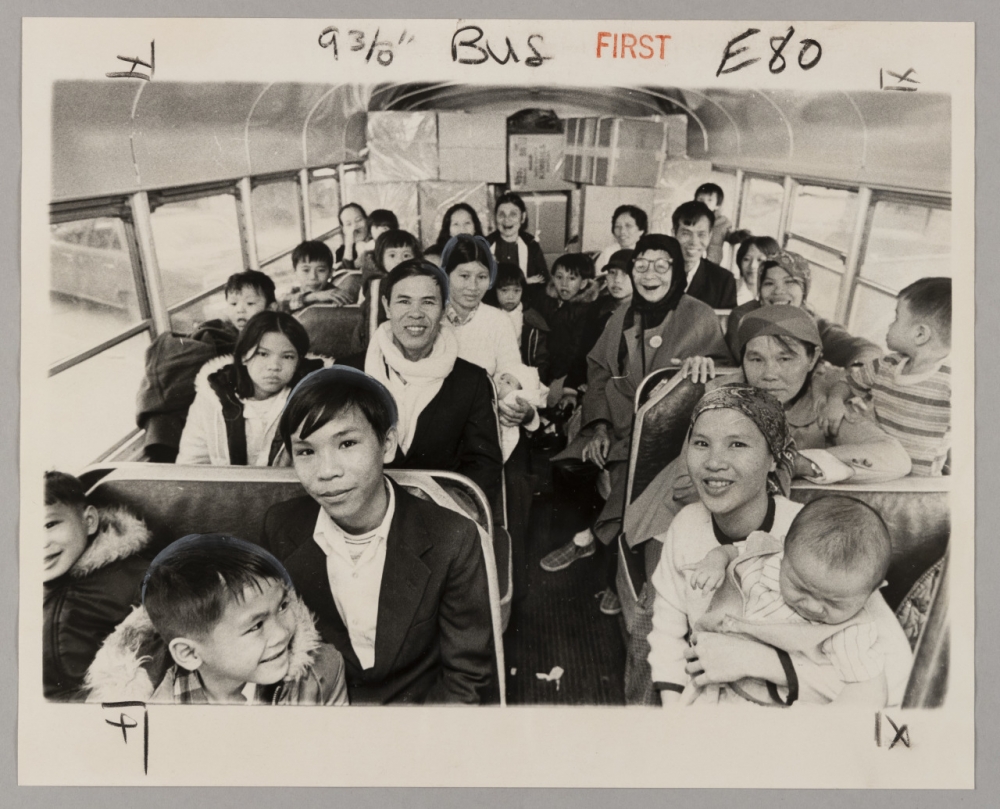

(THNOC, 2021.0175)

In 1975 Archbishop of New Orleans Philip Hannan visited Fort Chaffe to minister to Vietnamese refugees, many of whom were Catholics. After his visit, Archbishop Hannan worked with the United States Catholic Conference and Catholic Charities of New Orleans to relocate thousands of refugees to New Orleans. They arranged for each refugee to have their own sponsor, which included businesses, families, and individuals who provided housing and financial resources. The photograph above depicts a group of these refugees taking a bus from Fort Chaffee to the New Orleans area. Over the following years, thousands more refugees independently settled in the area, and communities began to form in New Orleans East, where the Department of Housing and Urban Development built public housing at the Versailles Arms.

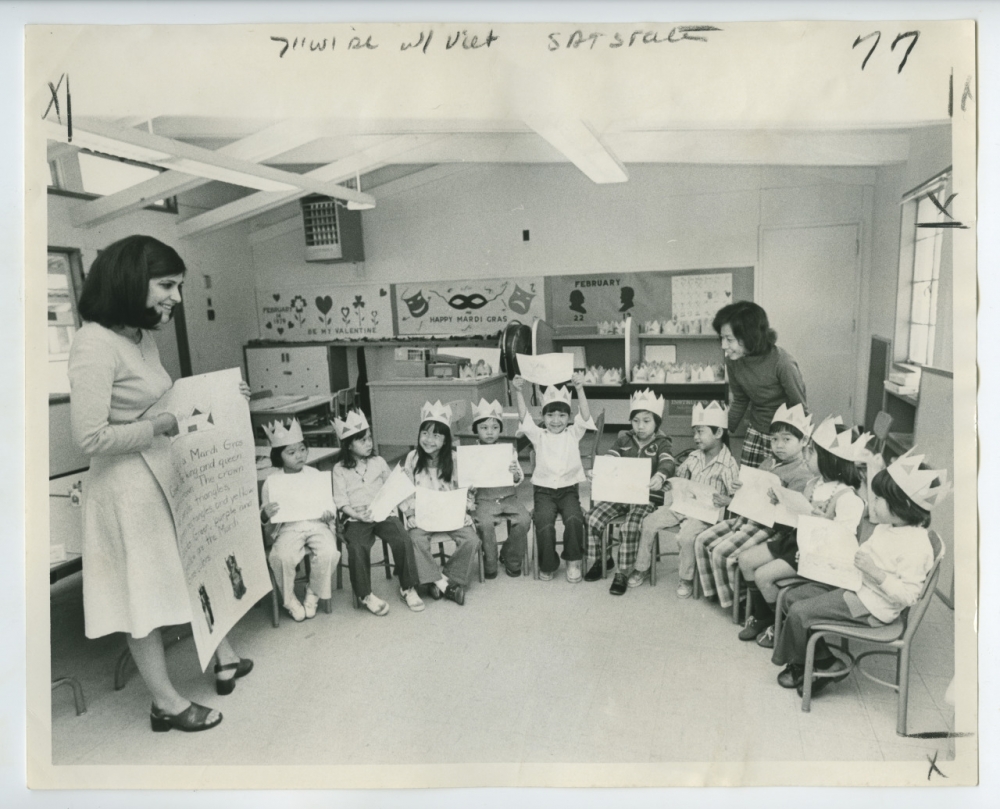

(THNOC, gift of Mark Cave, 2018.0558.1)

Catholic Charities of New Orleans also provided citizenship classes and English language education to refugees of all ages. The picture above depicts a classroom of Vietnamese children at Eisenhower School in New Orleans with their English teacher, Anne Whited, and a Vietnamese teacher’s aide, Dieu Tran, in March 1976. In the photograph, Whited is teaching about Mardi Gras kings and queens, while the children wear crowns on their heads. It was published in The States-Item newspaper along with an article about Vietnamese schoolchildren.

(THNOC, 2007.0001.33)

This photo depicts a group of religious sisters, likely Vietnamese nuns, gathered at the UNO Lakefront Arena to welcome the arrival of Pope John Paul II in 1987. They may have been members of a local religious order called Daughters of Our Lady of the Holy Rosary, but also may have traveled in for the event. When he arrived, Pope John Paul II delivered an outdoor Mass in the pouring rain. Upon their arrival in New Orleans East, Vietnamese Catholics worshipped outdoors and in mobile homes until a church was built for them in 1983. Mary Queen of Vietnam Church became the first Catholic church in the US to offer services in Vietnamese, and it continues to serve as a cultural center for the Vietnamese community. Its annual Têt festival, celebrating the Vietnamese lunar new year, showcases Vietnamese food and culture to the greater New Orleans community.

(THNOC, gift of Dam Nguyen, MSS 810.19.2)

Since 2017, The Historic New Orleans Collection has collected 28 oral histories from the New Orleans Vietnamese community as part of the “Viet Chronicle” oral history project. This is a photograph of one of the interviewees, a New Orleans East Resident who left South Vietnam in 1977 with her soldier husband and six children. Upon arrival they lived in Gretna before joining her husband’s mother and other family and friends in Versailles in New Orleans East. Her husband took a job at Schwegmann Supermarket before going on to work at the Avondale shipyards while she peeled shrimp and shucked oysters for extra money. Oral histories like these will be instrumental for an upcoming THNOC exhibition in April 2025 commemorating the 50th anniversary of the fall of Saigon, in which first-generation Vietnamese immigrants and veterans will have the chance to tell their story in their own words.

Mexican Immigrants

Louisiana has always been an important point of contact between Mexico and the United States. New Orleans’s relationship with Mexico dates to the Spanish Colonial period, with a steady but small flow of immigration to the city until the 21st century. The first Spanish-language newspaper in the United States, El Misisipi, began in New Orleans in 1808, catering to a Spanish speaking population. Mexican Presidents Benito Juarez and Porfirio Díaz used New Orleans as a base to plot revolution in the mid-19th century. In 1884, President Díaz financed a large Mexican pavilion at the World’s Industrial Cotton Centennial Exposition. The enthusiastic reception of the 8th Cavalry Mexican Military Band led by Encarnación Payen at that fair was the subject of a Prospect.5 exhibition about the impact that these musicians had on New Orleans musical traditions and the music publishing business.

Mexican immigration to New Orleans throughout the 20th century was slow when compared to other parts of the American South. Mexican workers came to the United States during both world wars to assist with the war effort, boosting agricultural and factory production. Deportations followed the World War II Bracero Program, which strained the relationship between the two nations. Louisiana was not a primary destination during either conflict and did not see the same increase in immigration as the Southwestern states did. In the late 20th century, Mexican immigrants came to New Orleans to work in the oil industry, in construction, and in the shipyards, but did not settle in the area. Instead, these transnational migrants, who were mostly men, worked in New Orleans and returned home on a seasonal basis. A natural disaster at the dawn of the 21st century would change these patterns, leading to a huge increase in Mexican immigration.

(THNOC, gift of Sharon Jacques, 2020.0009.2)

After Hurricane Katrina devastated the Gulf Coast in 2005, thousands of Mexican immigrants came from Mexico and Texas to rebuild the city. This 2016 sculpture is titled “Tribute to the Unknown Hispanic Worker that Helped to Rebuild the City of New Orleans after Katrina.” It was created by New Orleans-based Cuban artist Luis Cruz Azaceta and was included in THNOC’s Art of the City exhibition. The workers referenced in the title engaged in dangerous work demolishing and rebuilding flooded homes, and were exposed to toxins and harmful substances as well as unsafe working conditions. In the wake of the hurricane, President George W. Bush temporarily suspended immigration enforcement laws to make it easier for American contractors to hire workers quickly, but he also suspended certain labor laws that put them at risk of abuse and wage theft. Additionally, many of these Mexican immigrant workers were targeted by immigration authorities and deported without being paid for their work.

For those who did stay, steady employment allowed these workers to bring their families to live with them in New Orleans. Between 2000 and 2010, the Mexican population nearly doubled, to approximately 15 thousand people. Mexicans are now the second largest Hispanic community in New Orleans behind Hondurans. While many Mexican immigrants worked in construction, others opened businesses to serve their fellow immigrants; food trucks offering tacos and other Mexican fare soon began popping up around construction sites, giving New Orleanians a taste of the quick-service cuisine long enjoyed by neighboring Texas. Many Mexican residents began settling in New Orleans East alongside the Vietnamese community, as well as in Kenner alongside the existing Honduran community.

(THNOC, gift of Evelyn Caruso, 2020.0067.1)

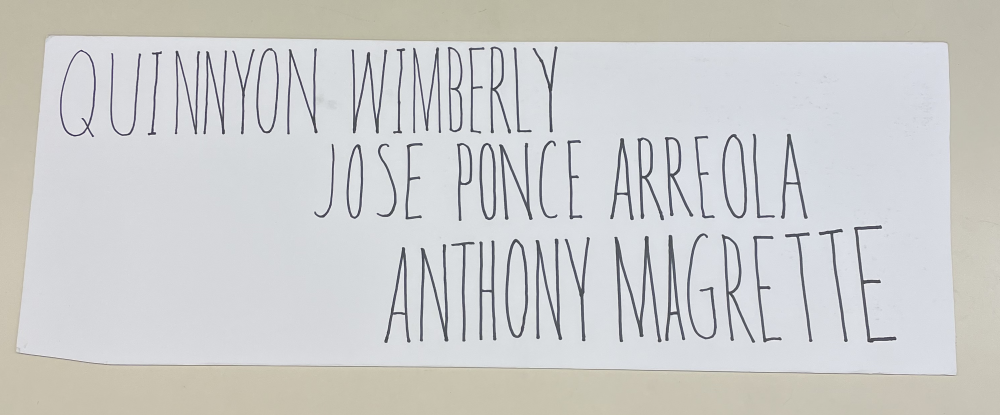

In October 2019, the Hard Rock Hotel building at the corner of Canal and North Rampart streets, which was under construction, collapsed. Dozens of construction workers were injured, and three died. This handwritten sign, which was donated to The Historic New Orleans Collection after a protest, displays the names of the three deceased men, whose bodies were not removed for ten months while investigations were underway as to the cause of the collapse. One of the deceased was Jose Ponce Arreola, who was born in Guachinango, Jalisco, Mexico and immigrated to New Orleans around 2005. At 63 years old, he had been working construction in New Orleans for 15 years and was preparing to retire and return to Mexico.

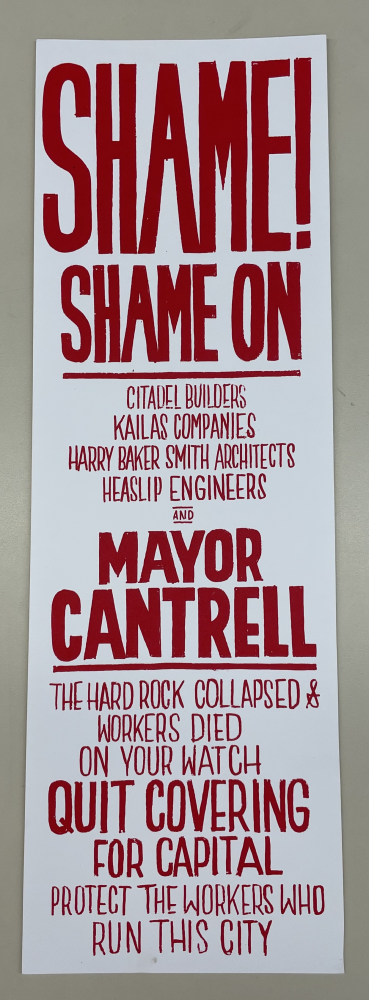

(THNOC, 2020.0066)

This sign was made and carried by local New Orleans printmaker Paul Portis at the same protest in January of 2020, when a group of approximately 100 New Orleanians gathered near the site of the building collapse site on the edge of the French Quarter and marched to New Orleans City Hall. Those who gathered expressed their outrage at the city's handling of the disaster and demanded accountability and transparency. As the year unfolded, 2020 became a year of unprecedented nationwide mass protests and civil unrest over the murder of George Floyd and police brutality, including many in New Orleans.

These protest signs are representative of what archivists call rapid response collecting, where museums acquire new objects to document history as it is happening. This dispels the myth that only old things are worthy of being preserved. Objects and life stories in our world have historical value, and collecting institutions are challenged to keep up with current events to document history as it unfolds. THNOC encourages community members to contribute to archives to expand our understanding of the past, present, and future of our diverse community through material culture.

About The Historic New Orleans Collection

Founded in 1966, The Historic New Orleans Collection is a museum, research center, and publisher dedicated to the stewardship of the history and culture of New Orleans and the Gulf South. Follow THNOC on Facebook or Instagram.