“Coming to New Orleans” is a new series, presented in conjunction with American Democracy: A Great Leap of Faith, that tells stories of New Orleans immigration history through items in our holdings. Read the first part of the series, a timeline that looks at New Orleans immigration in the context of immigration to the US, here.

In the decades following the Civil War, immigration to New Orleans slowed dramatically. In total population, New Orleans continued to fall from its pre–Civil War height as the fourth largest city in the US. Despite these trends, New Orleans’s Black population doubled after emancipation, and thousands of immigrants arrived from Southern and Eastern Europe as well as Asia. Nativist national policy affected immigration to the city, as the US government began to restrict immigration during this period, a trend that would reach its zenith in the 1920s. The period between Reconstruction and the US entry into World War I was also a time of immense technological and economic change in New Orleans, and immigrants played a pivotal role in the future of the city as a hub of international trade.

Filipino immigrants

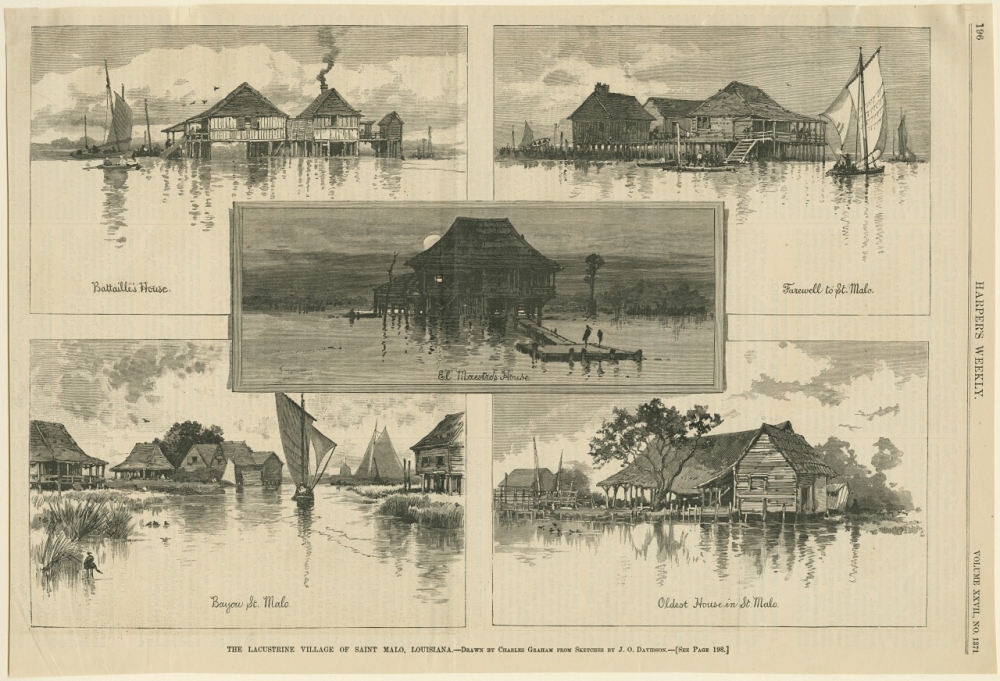

The Lacustrine Village of Saint Malo, Louisiana (THNOC, 1974.25.4.133 i-v)

According to some scholars, Filipinos first arrived in Louisiana in the 1760s aboard New Orleans–bound Spanish galleons. Though this date is contested, they are now recognized as some of the first Asian settlers in the US. St. Malo, a fishing village they established south of Lake Borgne by the 1840s, is the first significant settlement of Asians in the country.

These illustrations of St. Malo’s raised cypress dwellings (based on bahay kubo stilt houses common in the Philippines) appeared in an 1883 issue of Harper’s Weekly magazine. The images were accompanied by a travelogue written by New Orleans–based journalist Lafcadio Hearn and aimed at a national audience. Hearn describes the residents of the village, who were all male and spoke Spanish and “a Malay dialect,” and the remote location that kept their existence largely unknown until the 1880s. The settlement was destroyed in the 1915 hurricane, but Filipinos had established another fishing village across the Mississippi River in Bayou Barataria sometime in the late 19th century. That settlement, known as Manila Village, was developed with the express purpose of producing dried shrimp, a common flavoring in East Asian cuisine, and was more visible and commercially successful than its predecessor. Also built on stilts, Manila Village was destroyed in Hurricane Betsy in 1965 and is now almost entirely submerged by coastal erosion, though the area remains popular with local fishermen.

Diary of Celina Margaret Padilla Hidalgo (THNOC, 2018.0060.1)

After Spain ceded the Philippines to the US in 1898 at the conclusion of the Spanish American War, Filipinos could move freely in the United States as US nationals, and many came to New Orleans to join the Filipino community. In addition to working in the seafood industry in St. Malo and Manila Village, Filipinos who spoke English and attended US schools and colleges entered a variety of professional fields, including business, engineering, and medicine, and served in the military during both world wars.

In 2018, THNOC acquired four diaries belonging to Celina Margaret Padilla Hidalgo, a Filipino woman who lived in Louisiana in the 1930s and early 1940s. Her first diary recounts her interactions with the Filipino community in Jefferson Parish, including her participation in the Filipino Carnival Ball of 1941. Filipinos established many social and benevolent organizations in Louisiana dating back to the 1870s. The Caballeros de Dimas-Alang was founded in the 1920s and won the award for best float three years in a row in the Krewe of Elks Orleanians parade.

Chinese immigrants

The Quong Son platform as it appeared in 1906 (THNOC, 1991.22.9)

By the time of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, Chinese immigrants had already established communities in Louisiana. Many people from South China had come to the state in the 1860s after the Civil War. These newcomers were mostly male and were employed as low-paid contract workers on cotton and sugar plantations, where planters used them to replace the enslaved laborers who had toiled in their fields before emancipation. Chinese men were also employed as merchants, laundrymen, stewards, cooks, and factory workers. Their community continued to grow, and by the 1880s, a small Chinatown had developed on Tulane Avenue, anchored by the Chinese Presbyterian Mission on South Liberty Street. Skilled Cantonese fishermen also emigrated from San Francisco to New Orleans to fish in the wetlands. Despite their small numbers, they built a successful dried shrimp business in the 1870s by joining the Filipinos at Manila Village.

This photograph showing employees of the Chinese company Quong Son is from a photograph album that documents a cruise by members of the New Orleans Horticultural Society, passing through Barataria Bay to Grand Isle. The Manila Village platforms pictured were used to process shrimp. After the boats brought the shrimp to the platforms, they were immediately boiled in brine, sun-dried for three days, and, until a mechanized process for shell removal was introduced in the 1920s, crushed underfoot in what was called the “shrimp dance.” The dried shrimp were then sorted and sent up the waterways to the company’s headquarters in the French Quarter.

Green Dragon Brand Dry Pack Shrimp crate label (THNOC, 2010.0149)

The Quong Son Company was founded in 1873 by Lee Yuen, a former rice merchant. Quong Son specialized in the distribution of dried Gulf shrimp in the era before refrigeration. The local market for dried shrimp was small, so the company packed its products and shipped them to North American Chinatowns and to Asia from their headquarters at 525 St. Louis Street in the French Quarter. In the 1930s and ’40s, a small but lively Chinatown developed on Bourbon Street, just two and a half blocks away from Quong Son’s headquarters. The Chinese immigration ban was lifted in 1943, when the US and China became World War II allies, but other restrictions enacted in the 1920s limited the number of immigrants who could be admitted. As a result, it wasn’t until after 1965 that Chinese people could freely emigrate to the United States. Though the Chinese community in New Orleans has remained small, their impact has been felt in a handful of key industries, including restaurants and healthcare.

Sicilian immigrants

Sicilian immigration to Louisiana began in the 1830s with the importation of Mediterranean lemons. In the decades following the unification of Italy in 1871, thousands of Sicilian immigrants arrived aboard steamships at the Governor Nicholls Street Wharf in New Orleans. By 1875, parts of the Lower French Quarter had become known as Little Palermo, and Sicilian immigrants began to impact the economic landscape of the French Market. They eventually dominated the fruit trade in New Orleans, operating stalls in the French and Poydras Markets, running the docks and wharves where fruit was unloaded from steamships, and founding highly profitable fruit import businesses bringing produce from Central America.

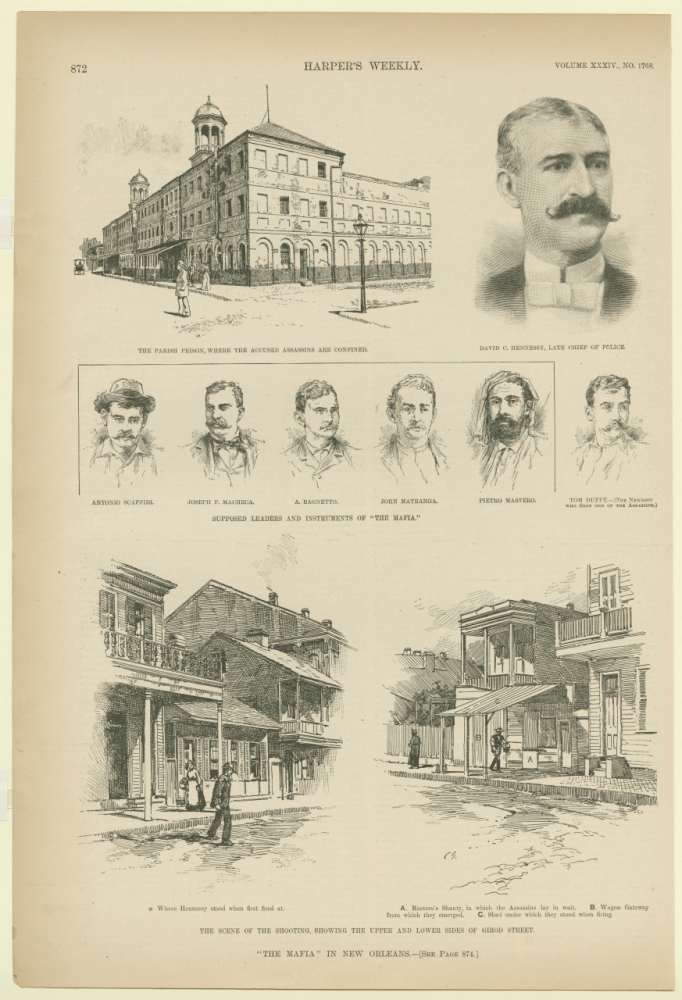

“The Mafia” in New Orleans (THNOC, 1986.174 i-v)

Despite Sicilians’ contributions to the city and its economy, anti-Italian sentiment was strong, driven by nativism and racism. Though Italians were European, many Americans did not see them as fully white. Violence broke out in 1891, when 11 Italian men were lynched by a large mob.

The lynching took place one day after 19 Italians—mainly Sicilians—were not convicted of the charge of murdering New Orleans Police Chief David Hennessey. This page from Harper’s Weekly magazine, published just three weeks after the murder, illustrates some of the people and places involved in the case. The title—“‘The Mafia’ in New Orleans”—and the images of the accused reveal white New Orleanians’ fear of these new immigrants. Though fanned by ethnic hatred and fear, the mob was led by politicians who had economic and political motivations beyond criminal justice. One of the men pictured, Joseph P. Macheca, was a native New Orleanian of Sicilian descent and a powerful merchant who dominated the fruit import and wholesale industry. After the massacre, Macheca was dead, and one of the leaders of the lynch mob took over the docks and the businesses that Macheca had created.

Day Dress from Sicilian–New Orleans family (THNOC, 2023.0001.1)

In the early 20th century, Sicilian immigrants began expanding out of the produce market into the restaurant and grocery businesses. This brown brocade day dress was worn by Mary Caliva Danna, who emigrated from Sicily in 1882 with her two children to join her husband Gesuardo in New Orleans. They soon opened a fruit stand that later evolved into a small grocery store. The sturdy dress, with an underskirt made of repurposed cotton flour sacks, reflects the role that working women played in the assimilation of Sicilian immigrants into the grocery business. Their legacy lives on in local institutions such as Central Grocery.