So much of New Orleans’s musical culture rests on its diversity, of styles, practitioners, and influences. The music of the African diaspora is a big part of this story—itself driven by diverse experiences and culture. A closer examination of some of these stories, particularly a few from the 18th and 19th centuries, can further elucidate not only the city’s musical heritage, but its social and cultural history as well.

Learn more about these traditions in THNOC's virtual exhibition New Orleans Medley: Sounds of the City.

Territorial period: African music forging American culture

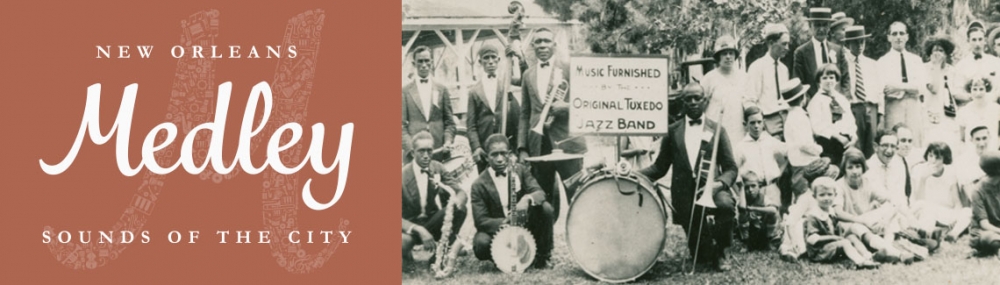

Edward Kemble’s illustration “The Bamboula” is a rare visual depiction of the activities in Congo Square, though Kemble never visited New Orleans and made the drawing in the late 19th century. (THNOC, 1974.25.23.54)

As New Orleans became American in the first decade of the 19th century, a musical tradition that can be traced to the early days of the colony continued in the city’s back-of-town, in the less developed areas away from the Mississippi River near where the French Quarter meets Tremé. Here, free and enslaved people of African descent gathered on Sundays and shared their varied musical traditions—typically centering on the rhythms sounding from drums and captured in the steps of dancers.

It was during these years in which visitors to the city began documenting these musical gatherings. Two such records are preserved in the travel accounts of visiting white men on display in THNOC’s virtual exhibition New Orleans Medley: Sounds of the City.

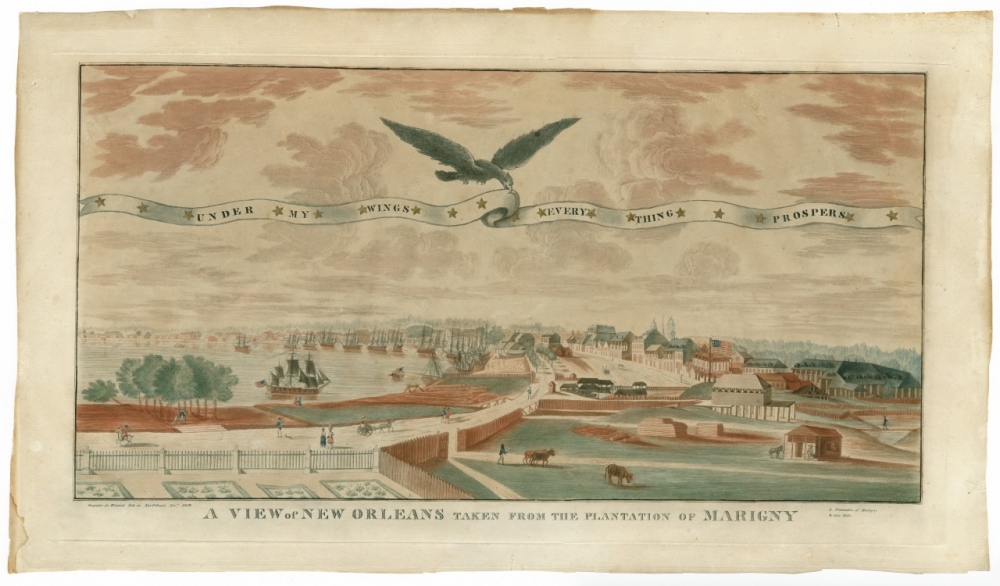

An image by John L. Boqueta de Woiseri shows New Orleans following the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. (THNOC, the L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1958.42)

The French author Pierre Louis Berquin-Duvallon’s Travels in Louisiana and the Floridas (1802) and Christian Schultz in his Travels on an inland voyage (1810) document, among other things, a slice of the musical life of New Orleans at the time. Their accounts bear witness to the diversity of people and customs participating in the events at Congo Square, and offer descriptions of the performances themselves.

Schultz’s description of the scene is thorough, albeit undercut by the author’s racism, reflected in his projection of an undesirable otherness and exoticism onto his subjects. He notes, “…twenty different dancing groups of wretched Africans, collected together to perform their worship after the manner of their country. They have their own national music, consisting…of a long kind of narrow drum of various size…three or four of which make a band.”

Though Schultz seems to recognize the diversity of participant groups, he immediately disregards this observation to synthesize the various cultures into one “national” style. But it’s the coalescence of these various cultures that illuminates the African American musical experience in New Orleans—and in the Americas generally. Though Schultz was unaware, his description positions Congo Square not only as a place where African musical culture was preserved, but as a locale where American culture was being forged through the interaction of Africans and people of African descent in New Orleans.

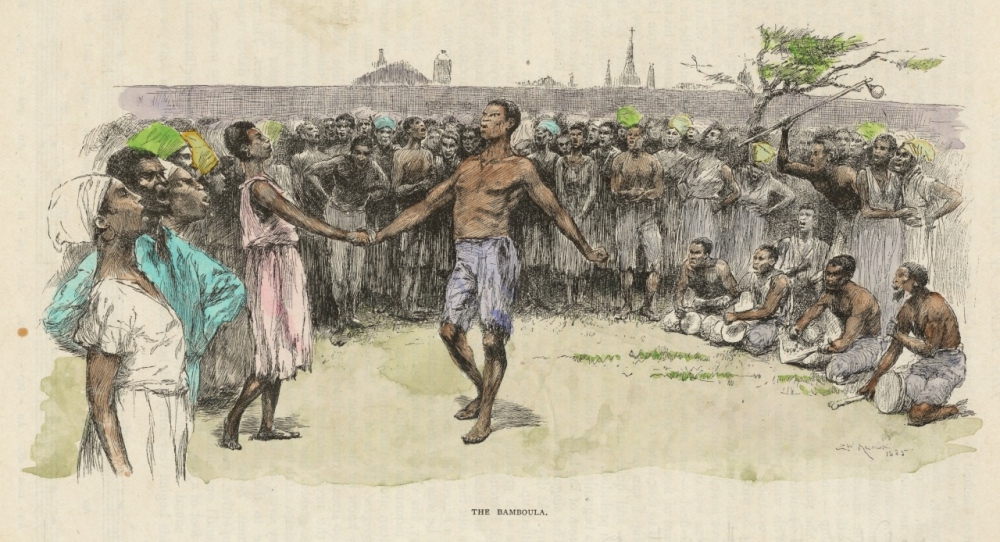

A photograph of Oscar Celestin’s Original Tuxedo Band provides a visual representation of black culture being consumed by a white audience in the early 1900s, a century after Pierre Louis Berquin-Duvallon made a similar observation. (The William Russell Jazz Collection at THNOC, acquisition made possible by the Clarisse Claiborne Grima Fund, 92-48-L.218)

In his slightly earlier account, Berquin-Duvallon makes a passing mention of the musicians at a Carnival celebration, writing, “The musicians are half a dozen gypsies, or else people of colour, scraping their fiddles with all their might.”

Though brief, the observation is significant, identifying the important role of black music and musicians within one of the city’s oldest traditions, even if Berquin-Duvallon’s prose dismisses its value—rendering it a practical footnote in the description of a ball. The account also implies by omitting the race of the ball’s attendees that the musicians were performing for a white crowd. This racially defined social and cultural exchange is one that permeates local New Orleans culture—from the time of Berquin-Duvallon’s visit to current performances of local culture by black New Orleanians, which are consumed by white locals and out-of-towners alike. A photograph presented later in the exhibition of Oscar Celestin’s Original Tuxedo Jazz Band performing at a picnic provides a poignant visual representation of this dynamic a century later.

Pre–Civil War: an ear turned toward Europe

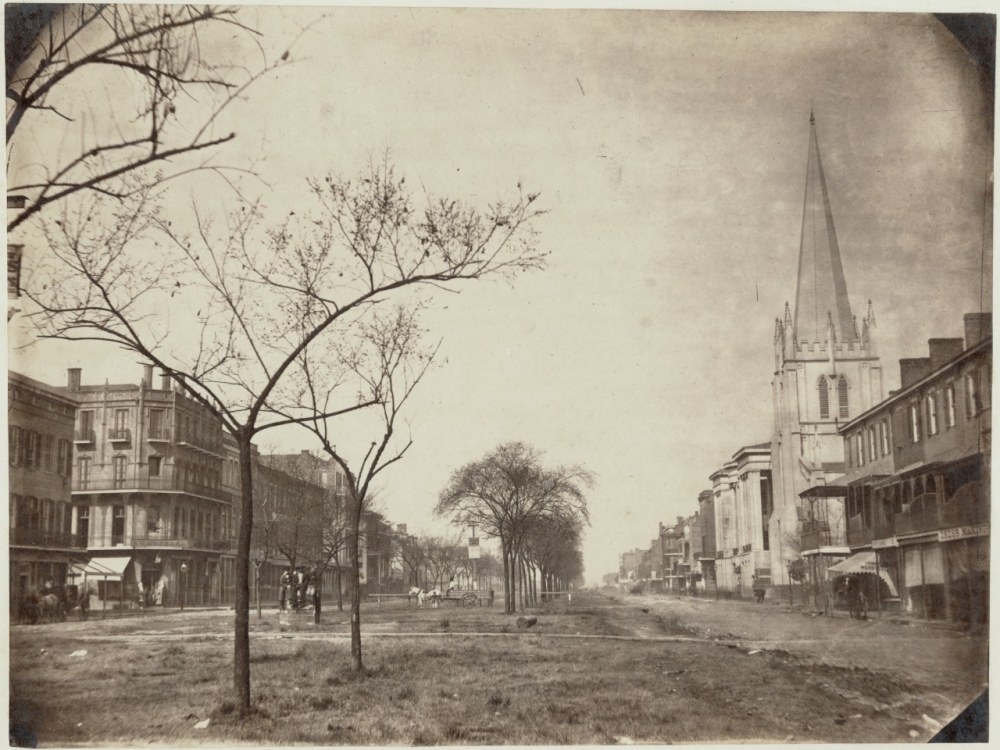

Canal Street pictured just before the Civil War. (THNOC, 1982.32.15)

The musical styles and practices of New Orleanians of the African diaspora included more than the traditions brought from Africa and the Caribbean. During the antebellum era, many Afro-Creoles (people who claimed both African and European heritage), both those free and held in bondage, embraced classical Eurocentric musical practice. This could have been for reasons of personal taste or perhaps to strengthen association with Europe in a time when whiteness was the most valuable form of personal capital.

In this time, an Afro-Creole orchestra, the Société Philaharmonique, played regularly to acclaim both in New Orleans and on tour along the East Coast. An 1865 account of the orchestra during a tour stop in Philadelphia noted that one of their French performances was among, “the most classical concerts we have ever visited.”

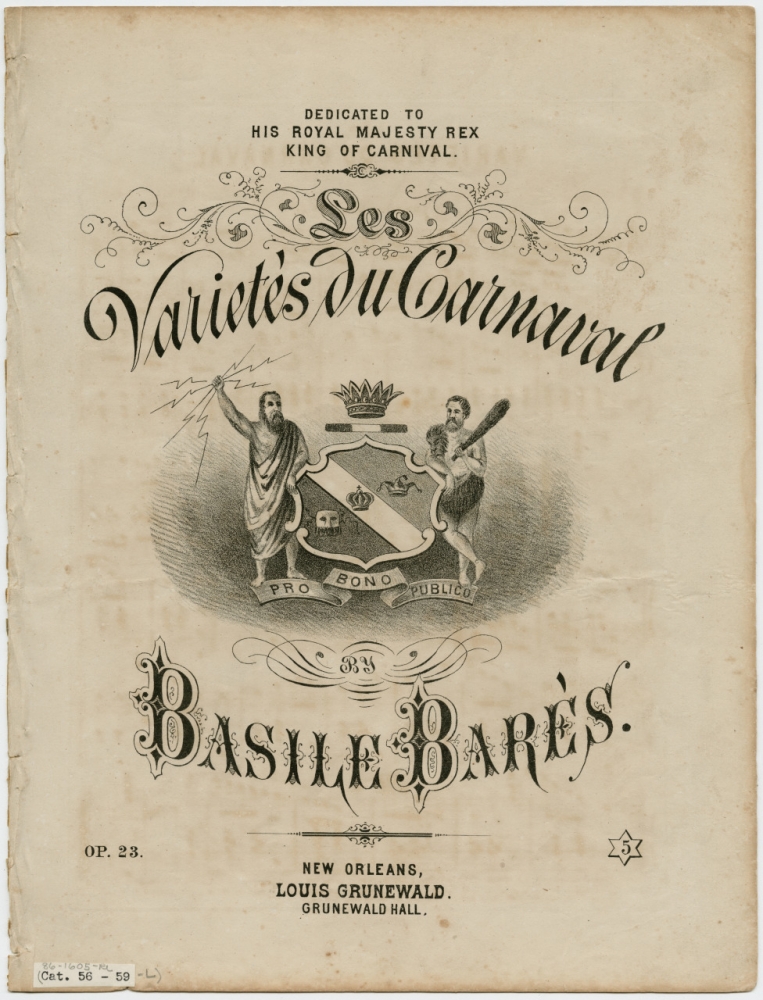

Basile Barès’s career took off after emancipation and included his piece Les Variétés du Carnaval, which was dedicated to Rex in 1875. (THNOC, gift of Boyd Cruise, 86-1605-RL)

Just before the Civil War, a precocious Creole teenager by the name of Basile Barès began exploring the possibilities of composition while enslaved by the owner of a local piano store. In 1860 a composition believed to have been written by Barès was published. Titled “Grande polka des Chasseurs à Pied de la Louisiane,” it is a rare example of a published musical work by an individual held in slavery. It is a startling accomplishment, a monument to the talent of Barès, and an exemplar of the diversity of cultural practice of locals of African descent.

Barès’ career flourished after the war. He became an internationally known composer and performer, playing to crowds locally and across Europe—including at the 1867 Paris Exposition.

After emancipation: back to the roots

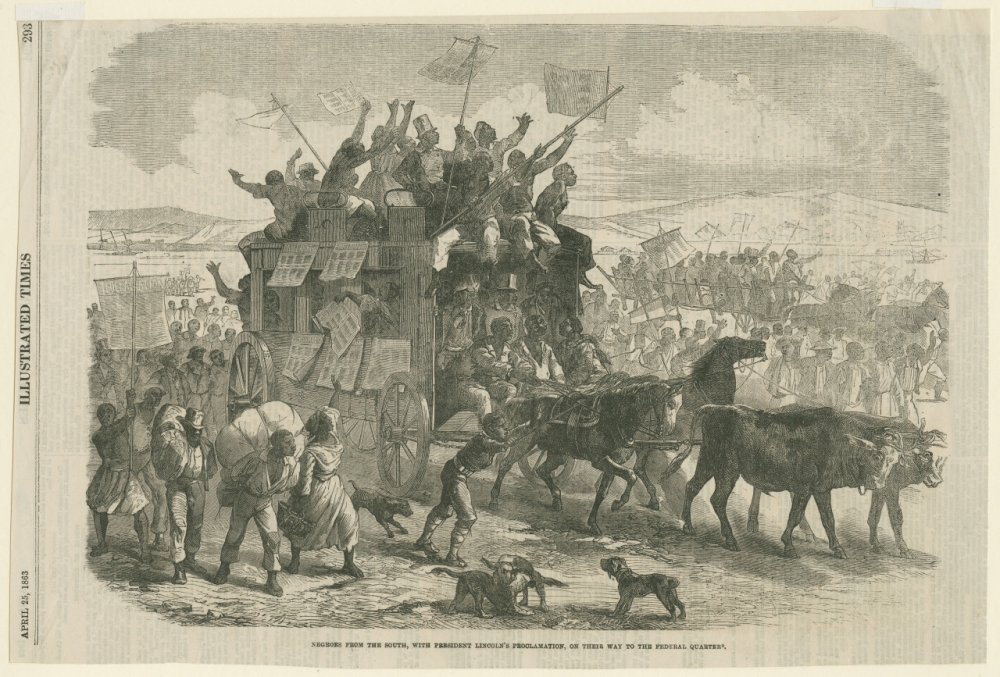

A London newspaper ran this sensationalized depiction of formerly enslaved individuals after the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. Emancipation in New Orleans, however, would not come until 1864. (THNOC, 1974.25.9.326)

For Barès, as for others in New Orleans, emancipation came on May 11, 1864, following the ratification of a new state constitution—just over 155 years ago. On the 11th of June, a jubilee was organized to celebrate the hard-won freedoms of so many New Orleanians.

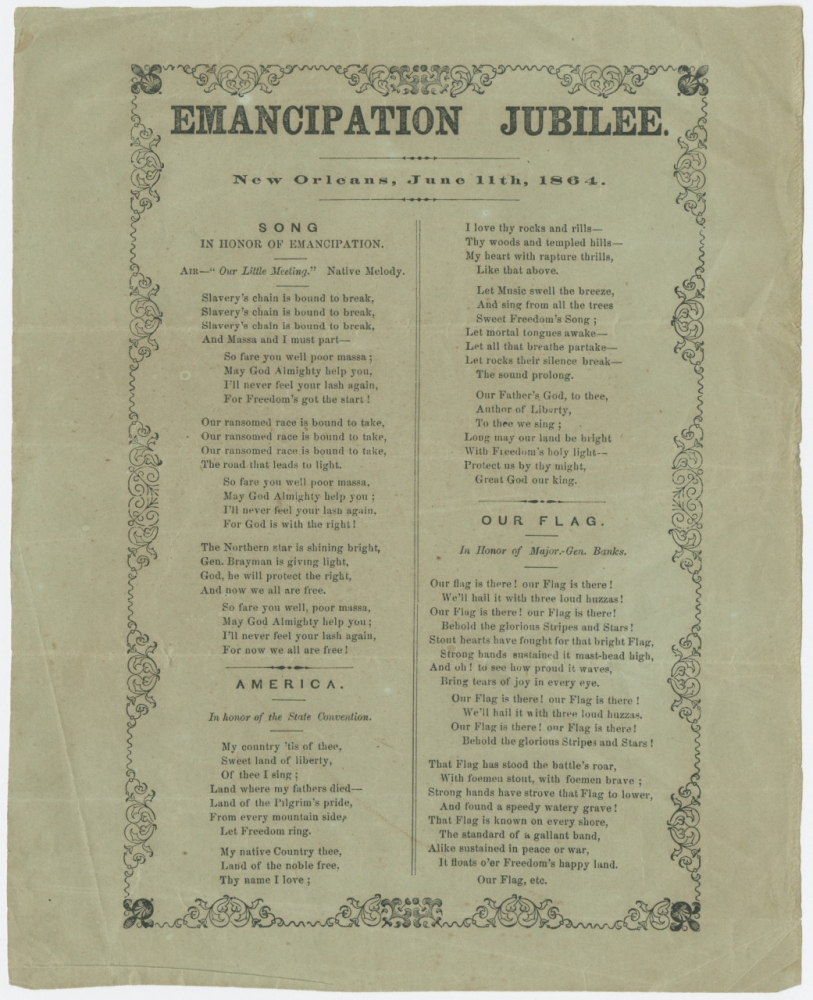

The event began, appropriately enough, in Congo Square, where thousands of people gathered to hear speeches and assemble for the day’s festivities. Schoolchildren opened the celebration singing what the New Orleans Era described as “a song in honor of emancipation,”—perhaps including the lyrics printed on the Emancipation Jubilee flyer on display in New Orleans Medley (lyrics transcribed below).

During speeches by Rev. S. W. Rogers and Mr. F. Boisdoré, the latter in French, local dignitaries Gov. Michael Hahn, Mayor Stephen Hoyt, and Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Banks appeared on the speaker’s platform to “tremendous cheers from the assembled thousands” and another song from the schoolchildren. This time they sang, “a national air,” perhaps “America,” otherwise known as “My Country ’Tis of Thee,” which is also printed on the Emancipation Jubilee handbill.

The program from the Emancipation Jubilee lists the lyrics for the songs, including the song in honor of emancipation (transcribed below). (THNOC, 91-720-RL)

After the speakers departed the podium, the crowd left Congo Square on a procession that wove through the city from Rampart Street to the intersection of Fourth and Prytania Streets, where they stopped at Banks’s home to give cheers for him, his wife, Hahn, President Lincoln, the Free State Committee, and the Army of the Gulf. From there the celebrants marched back through the Faubourg St. Marie, the French Quarter, the Marigny and back to Congo Square. And as with any proper New Orleans procession, this one was accompanied by music from a brass band.

Slavery’s chain is bound to break

Slavery’s chain is bound to break

Slavery’s chain is bound to break

And Massa and I must part –

So fare you well poor massa;

May God Almighty help you,

I’ll never feel your lash again,

For Freedom’s got the start!

Our ransomed race is bound to take,

Our ransomed race is bound to take,

Our ransomed race is bound to take,

The road that leads to light.

So fare you well poor massa,

May God Almighty help you;

I’ll never feel your lash again,

For God is with the right!

The Northern star is shining bright,

Gen. Brayman is giving light,

God, he will protect the right,

And now we all are free.

So fare you well poor massa,

May God Almighty help you;

I’ll never feel your lash again,

For now we all are free!

Seiferth was the co-curator of the exhibition New Orleans Medley: Sounds of the City, in 2019, which explored New Orleans's multifaceted musical heritage. Experience the exhibition virtually in a new 360-degree display.