Whether you mark Easter or Memorial Day as the beginning of the warm weather fashion season, the time for seersucker has officially arrived in New Orleans. The puckered fabric has been a staple of summer fashion for generations, but just how did the iconic material come to be?

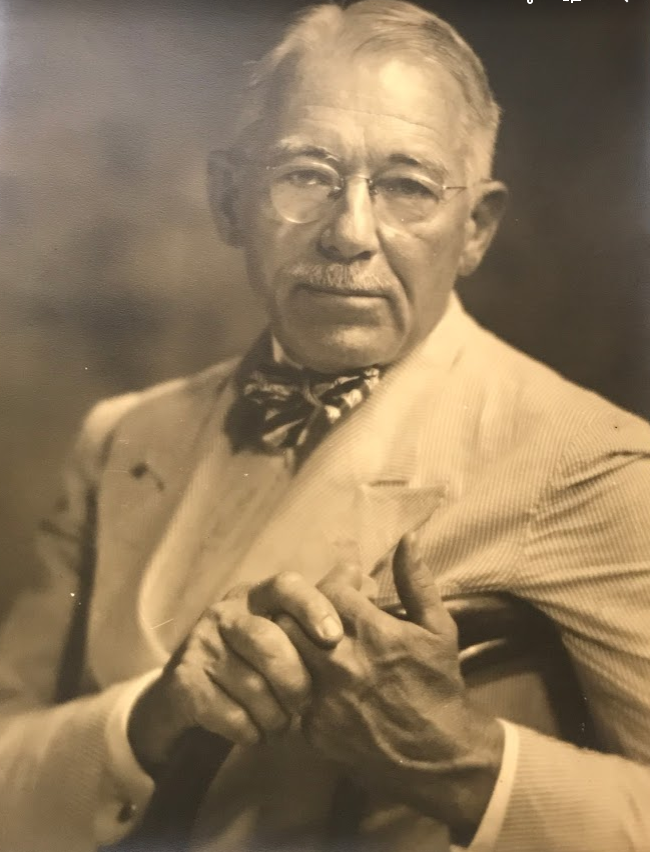

Local legend claims that New Orleans clothing manufacturer Joseph Haspel Sr. invented the seersucker suit in the first decade of the 20th century. Haspel had been manufacturing coveralls from the material for Louisiana factory workers and thought businessmen shouldn’t have to suffer in their hot offices (these were the days before air conditioning). Haspel’s production run started around 1909 at his New Orleans factory, and it was the Haspel seersucker suit that became ubiquitous as warm weather menswear in the South. Supposedly, while promoting his suits at a convention in Boca Raton, Florida, Haspel walked into the ocean up to his neck in his seersucker suit. He hung the suit up to dry that afternoon and wore it to the convention banquet dinner that evening, none the worse for wear.

The headquarters of Haspel at 517–531 Toulouse Street. Local legend claims that Joseph Haspel Sr. invented the seersucker suit. (Courtesy of the Vieux Carré Survey)

Obviously, this is a great origin story with New Orleans at the heart of it, but historical records tell us it’s not quite true.

Seersucker fabric has been around for centuries. Its name comes from the Persian phrase shir-o-shakhar, meaning “milk and sugar” for the alternating textures. The textile is made of cotton, linen, or silk (or combinations thereof), woven on a loom with threads at different tensions. As the fabric is woven through the tight and loose threads, it creates alternating stripes of texture. These smooth and puckered stripes are what make the fabric especially breathable, because it doesn’t lay flat against one’s skin. Often, one of these stripes is in a color—most often blue, but sometimes gray, green, tan, red, pink, etc.—making the iconic pattern so well known today.

A production still from Hush…Hush, Sweet Charlotte (1964) shows Joseph Cotton’s seersucker-clad character, “Dr. Drew Bayliss,” placing his hand on Bette Davis’s forehead. The film was set in Louisiana during the 1920s and ‘60s. (THNOC, 2014.0102.261)

First made in the sweltering regions of the Indian subcontinent, the striped and puckered fabric was exported to the European market by the 17th century. English and French textile manufacturers quickly adapted the term and the fabric for their own production. Seersucker fabric was exported to the American colonies by the early 18th century, often used for durable and cool curtains, mattress covers, and work clothing.

As a lightweight, hard-wearing fabric, imported seersucker was most often used for summer and work clothing in early America. Nineteenth-century Louisiana newspapers reveal hundreds of advertisements for the textile, often in association with other imported cottons and durable fabrics. Seersucker was available in many patterns, such as striped, checked, and plaid; an assortment of colors, most commonly blue or yellow; and could be guaranteed “Real India” or an “imitation” version. It could be purchased by the yard, as well as in finished forms such as pantaloons, vests, and various types of coats.

An unidentified man sports a seersucker suit in this ca. 1925 image by Joseph “Pops” Whitesell. (THNOC, gift of an anonymous donor, 2014.0198.1)

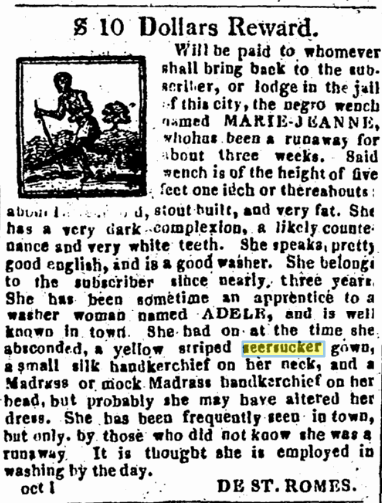

Because of its relative cheapness and durability, seersucker was commonly used for slave clothing. Runaway slave ads offer rare descriptions of personal appearances, behavior, and clothing, as described from the perspective of the enslaver. One 1821 ad described Marie-Jeanne, who was “stout built,” with a dark complexion, very white teeth, worked as a washerwoman, and was wearing “a yellow striped seersucker gown” and a “madras handkerchief when she absconded.” Following emancipation, seersucker was still a common working fabric, used for factory workers’ jumpsuits and the iconic railroad coveralls.

An 1821 runaway slave ad describes a woman named Mary-Jeanne as wearing a seersucker dress. Seersucker was used for work clothing in the South before and after slavery.

The first mention of “seersucker suits” in New Orleans newspapers is in an 1867 ad for Robert Pitkins’ Fashionable Clothing Emporium on Camp Street. Messrs Garthwaite, Lewis & Stewart also advertised seersucker suits that year, more than 40 years before Haspel claimed to invent it. Of course, the style of these suits isn’t exactly what we think of today. The “Leisure suit,” with loose pants, hip-length coat, and (increasingly optional) vest, all in matching fabric, did not become the prevalent male fashion until the last decade of the 19th century.

More mentions of seersucker suits come in the 1880s. The May 6, 1886, edition of the Daily Advocate in Baton Rouge declared that “Straw hats and seersucker suits are all the go in Franklin.” Fashion reports from Washington, DC, describe congressmen in seersucker about this time (predating the modern Congressional summer tradition of “Seersucker Thursdays” by a century). In 1890, George Francis Train made a trip around the world in a seersucker suit, saying to the Daily Picayune, “Universe laughed at my seersucker suit. Now I laugh at universe. I am the seer. Universe is the sucker.”

A mother holds a child, identified as Teddy St. Leger, who wears a seersucker jumper in this 1935 photograph. (THNOC, 2001.79.62)

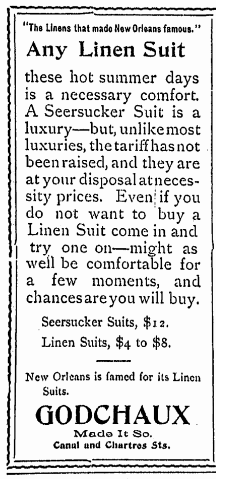

By turn of the 20th century, ads for local companies begin to appear that challenge Haspel’s claim as inventor of the modern seersucker suit. In 1897 the Godchaux department store advertised seersucker suits for $12 (inset image). In 1903, The Truefit, Ltd. advertised tropical clothing, including “Genuine Seersucker suits.” Mayer Israel & Co. noted “Seersucker Coats and Trousers made to measure” in their 1906 summer advertisement. Mayer Israel, D. H. Holmes, The Stevens Store, and many other men’s clothing stores advertised “genuine” seersucker suits through the 1910s.

By turn of the 20th century, ads for local companies begin to appear that challenge Haspel’s claim as inventor of the modern seersucker suit. In 1897 the Godchaux department store advertised seersucker suits for $12 (inset image). In 1903, The Truefit, Ltd. advertised tropical clothing, including “Genuine Seersucker suits.” Mayer Israel & Co. noted “Seersucker Coats and Trousers made to measure” in their 1906 summer advertisement. Mayer Israel, D. H. Holmes, The Stevens Store, and many other men’s clothing stores advertised “genuine” seersucker suits through the 1910s.

As for Joseph Haspel, he was just 23 years old in 1909, working as a secretary at the Louisiana Clothing Co. Ltd. He joined his brother, Harry S. Haspel, and Heymas Abes in the firm Abes & Haspel on Chartres Street the following year. In 1916, Harry and Joseph took over the firm upon Mr. Abes’s retirement, changing the name to Haspel Brothers. Their company had a successful business manufacturing work pants, trousers, and overalls, and they moved the enterprise to a large new factory at St. Bernard Avenue and N. Broad Street in 1921. The first mention of Haspel summer suits in the Times-Picayune was not until 1922. Joseph Haspel patented a pattern for a wash-and-wear suit coat in 1937. Haspel seersucker and summer suits became increasingly popular in the 1940s and 1950s, around the time of Joseph Haspel’s notorious Atlantic dip. The company moved to a new location on Toulouse Street in the French Quarter, the former home of the Tropical Clothing Manufacturing Company, in 1947. Joseph’s son, Joseph Haspel Jr., took over the company in the late 1950s, just before the elder died on December 29, 1959.

Members of the Valley of Silent Men social aid and pleasure club don seersucker suits in this 2012 photo. (THNOC, gift of Charles M. Lovell, 2015.0508.6)

Although Joseph Haspel may not have been the first manufacturer of seersucker suits, New Orleans was at the epicenter of seersucker fashion at the turn of the 20th century, and Haspel’s company played a large role in promoting the garment through the mid-20th century. As we progress further into the 21st century, seersucker is being worn in increasingly fashionable ways. However you wear the puckered fabric, stay cool this summer!

About The Historic New Orleans Collection

Founded in 1966, The Historic New Orleans Collection is a museum, research center, and publisher dedicated to the stewardship of the history and culture of New Orleans and the Gulf South. Follow THNOC on Facebook or Instagram.