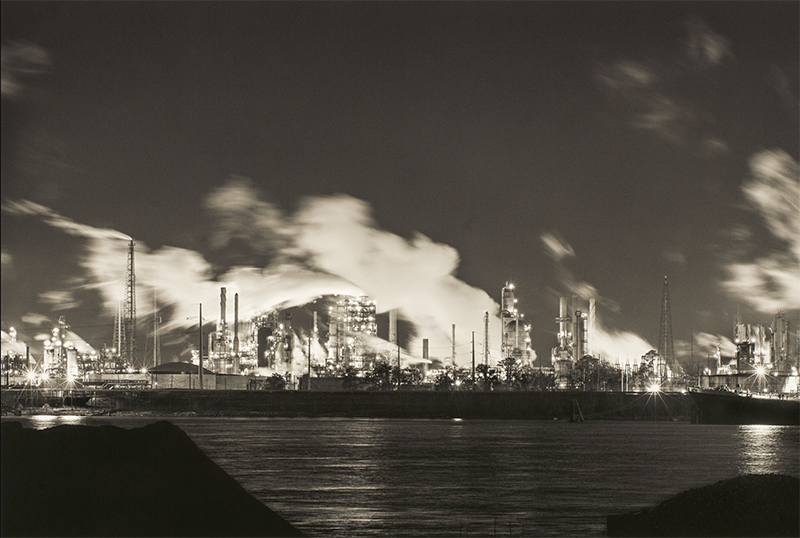

Scene from Norco, a sci-fi adventure game based on the creator’s Louisiana hometown. (Courtesy of Geography of Robots / Raw Fury)

If you’ve driven the River Road between New Orleans and Baton Rouge, or caught a glimpse of the flickering refineries off in the distance from I-10, you probably have a sense of the heavy industrial presence all along the lower Mississippi River. You’d be forgiven, however, for not really knowing what goes on here—or not wanting to find out. When these behemoths tower over your tiny hometown, though, you have little choice but to get acquainted, and perhaps even come to find beauty in this alien landscape. Such was the case for the game developer and geographer known pseudonymously as Yuts.

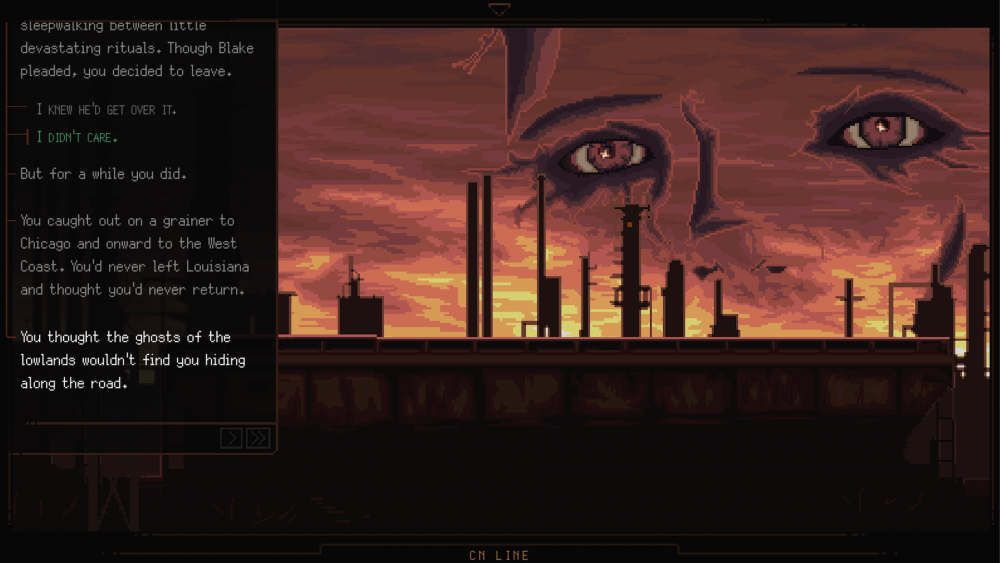

Norco, the video game that Yuts and the collective known as Geography of Robots created about his hometown of Norco, Louisiana (approximately 25 miles west of New Orleans), launched to critical acclaim in March, and has been billed by the game publishing platform Steam as “a Southern Gothic point-and-click narrative adventure that immerses the player in the sinking suburbs and verdant industrial swamps of a distorted South Louisiana.” Distinguished by its hauntingly gorgeous pixel artwork and engrossing storyline, Norco won the Tribeca Film Festival’s inaugural award for game design and has captivated gamers and non-gamers alike.

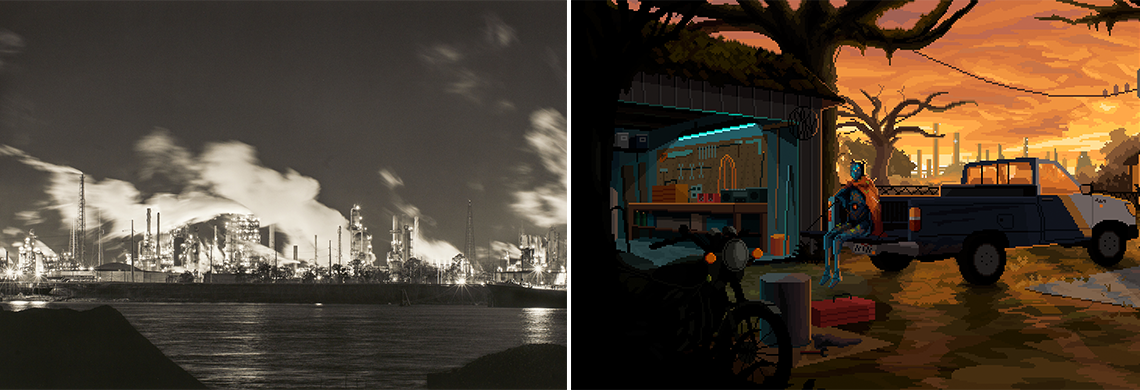

The town of Norco—or, rather, the petrochemical complexes lining the riverfront in Norco—also recently graced the cover of Enigmatic Stream: Industrial Landscapes of the Lower Mississippi River, by photographer Richard Sexton and published by THNOC. I asked Richard to join me for a conversation with Yuts to discuss what makes Norco such a compelling artistic subject. The following is an edited transcript of that conversation.

+++

Oil refineries loom large in Norco, as they do in the town for which it is named. (courtesy of Geography of Robots/Raw Fury)

Yuts, can you tell us about yourself and the game Norco?

YUTS: I’m from Norco, grew up in Norco, went to UNO, lived in New Orleans up until about three years ago, when my partner accepted a job in the Blue Ridge Mountain region of Virginia. The game itself uses a lot of classic adventure-game tropes, but at its heart, it is more of an interactive piece of media. It has a lot of nontraditional gameplay elements. It’s intended to be a composite look at not only the region in Louisiana, but also the Trump era. The three acts of the game are in many ways slightly disparate, but they all do tie into the industrial landscape of the river parishes and the suburbs of western greater New Orleans, so Kenner and Metairie. The narrative of the game is constructed in a way where the landscape takes primacy in many ways. It’s really an exploration of New Orleans’s landscape, and also the types of people and personalities and communities and cultures that it has created and has the potential to create.

View of Norco petrochemical facilities from the west bank levee in Hahnville, Louisiana, featured in Enigmatic Stream by Richard Sexton. (THNOC, 2015.0364.112; ©Richard Sexton)

Richard, these landscapes were the focus of Enigmatic Stream. A lot of our readers know your work, but can you also briefly introduce yourself and tell us about the inspiration behind Enigmatic Stream?

RICHARD: Sure. I’m not a native of New Orleans. I moved here in 1991 from San Francisco, where I’d gone to art school and lived for 13 years. I started my career there. And, actually, interestingly enough, one of the first things I did when I got to New Orleans, through some friends that we had met, is I joined the Krewe of Underwear, which was one of the sub-krewes of Krewe du Vieux. We had a krewe meeting in a place I had never really heard of before: Norco. That was my first experience, and I was like, Wow, I cannot believe that anybody lives here. Because all that you see is this looming metropolis past the swamp that is just a bunch of petrochemical and oil refining, and there’d also just been an explosion out there.

YUTS: That’s right.

RICHARD: The folks whose house we were going to had to move because all the windows had gotten blown out. So that was quite an interesting initial foray into the world of Norco. But to fast-forward a bit, I didn’t really become intimately familiar with the river parishes until I did a book on it, Vestiges of Grandeur, which was basically devoted to the late 18th and early 19th century agrarian sites. It was about the plantations, and sugar farming, which was the original development by the Europeans along the river. But in the course of doing that I drove every mile of the River Road, on each side of the river, between New Orleans and Baton Rouge, and I saw all this other stuff and was fascinated with it. Here, in the middle of a cane field, is an oil refinery. In just the middle of nowhere. It isn’t even a town. It’s in an unincorporated area. That’s pretty unusual, to see that sort of heavy industry in an otherwise agricultural setting.

So, I always wanted to go back and focus on that, on how the landscape had transformed from the 19th to 20th century into something quite a bit different. Many people told me—that were native to New Orleans—“God, I had no idea this existed.” Unless you go there to explore it, or you’re from there, it’s kind of this lost zone, and there’s no recreational use of the river. I was just fascinated with it and had a very ambivalent attitude toward it, but it is so impressive in an Orwellian kind of way. That’s how I came to do Enigmatic Stream.

Norco draws inspiration from the childhood home and experiences of its creator, Yuts, and adds futuristic flourishes including an android named Million. (Courtesy of Geography of Robots / Raw Fury)

Yuts, hearing that perspective from Richard as an outside observer, how would you introduce your hometown of Norco to somebody who hasn’t heard of it?

YUTS: Well, Richard, I love hearing your perspective—we have a shared timeline from two different perspectives—because the explosion that you’re reference I’m assuming is when the cat cracker exploded in ’88.

RICHARD: Yes, that was before I lived here, but everybody was talking about it.

YUTS: Yes, it was still at the forefront of everyone’s minds. It had such a lasting impact in many ways on the community. At the time, I was a baby. My family’s house is not many blocks from the Shell oil refinery, and our windows got blown out as well. I was actually sleeping in a crib, and the window was right above my head, and there was a sheet hanging above the window, so it caught all of the glass, and the glass rained down on me. According to my parents, I slept through it.

Oh, my gosh.

YUTS: I slept through it, so my mom thought I was dead, but she brushed the glass off of me, shook me awake, and we evacuated to my Grandma’s house in LaPlace [10 miles west of Norco]. That’s the resident’s perspective of that event. And then the timeline that you’re describing, that’s when momentum really started to build for the Diamond community to organize for a buyout, which I don’t think happened until 2002. There was a lasting legacy from that explosion.

You had mentioned there’s no recreational areas along the Mississippi River, and that is absolutely true. A big portion of the river there, the batture is fenced off, but when me and my friends were kids—in the game there’s a line that the refinery was “the jungle gym of your youth”—we used to sneak into the refinery, climb around on the pipes. We made do recreationally with what infrastructure and architecture was available to us along the Mississippi River batture. Because there’s no topography or elevation to speak of in south Louisiana, the only way to get a vantage of the landscape is to climb up on the levee or be on an interstate bridge, or climb to the roof of a building. Climbing abandoned buildings was another popular pastime when I was a kid and a teenager. Those spaces become quasi-public spaces just through that type of creative appropriation.

A so-called “fence-line” house adjacent to the Valero refinery in Meraux, Louisiana, photographed for Enigmatic Stream by Richard Sexton. (THNOC, 2015.0364.49; ©Richard Sexton)

Hearing about your childhood and experiences in Norco reminds me of some of Richard’s images in Enigmatic Stream—I’m thinking of the ranch house with the refinery of the background, for example. Richard, did you ever interact with locals in Norco?

RICHARD: I had a good friend who grew up in Edgard, his wife was the daughter of a chemical engineer. In terms of meeting people, first of all, that’s a dangerous thing to do. The people coming up to me were like the security at the oil refineries trying to tell me that even though I was standing on public property looking at a public view of something that I couldn’t take any pictures. I got reported to Homeland Security and the FBI called me and all this other stuff, because they don’t really want this kind of publicity whatsoever.

To get back to Norco, specifically: Norco is on the cover of the book. That was not an accident. I photographed it from Hahnville across the river, so that I could see the whole expanse of it. I would tell people, if you want to go to one place on the river to see everything, go to Norco. Go out there on the levee, you’ve got the Bonnet Carré Spillway. Across the river, you can see Waterford I, II, and III, and you can see the Taft-Carbide plant, and you’ve got, just upriver, Little Gypsy (power plant), and then you’ve got all of Norco below you. It’s like the one place you can go and stand and just see all of that all around you.

When the river was low and the batture was dry, the local people would drive their pickups down to watch the sunset over the river. There would be tankers or container ships docked there. I took pictures of people fly-fishing. Everywhere else there’s levees, but there’s an access point to the river, and you would see people going there to just hang out, drink beer. I tried to photograph that. I was very proud of two images, you mentioned one of them that was in Meraux of a ranch house and an SUV in the driveway and the Valero oil refinery in the back.

YUTS: I was just looking at that last night, very stark image.

Sexton occasionally had run-ins with law enforcement while photographing Engimatic Stream, including when he was taking this image of a house adjacent to the Entergy Little Gypsy power plant. (THNOC, 2015.0364.52; ©Richard Sexton)

RICHARD: Yeah. And then there’s another that’s just above Norco, and they called the sheriff on me on that one, but I photographed a ranch house on the River Road with Little Gypsy power plant right behind it. I like to do those things because I think that it’s important for people who are in some leafy suburb, where everything seems great with the world, to understand when they go out and they crank their car up, or they plug the toaster in, where that technology and infrastructure needed for them to be able do these simple little things comes from, and what it looks like.

It’s revealed so readily on the River Road in the river parishes, because you do see: there’s an aluminum plant right in the middle of a cane field in Gramercy [about 21 miles upriver from Norco]. OK, that’s how they make aluminum, a common metal you’re using all over the place every day. You see all that bauxite dust all over the place: the trees are red, the road’s red, everywhere you look has got that all over it. You see that and get a very insightful view of the impacts that most people in their environments don’t get.

YUTS: My dad worked at that Gramercy facility for years. That bauxite, he used to come home and have to dig it out of his ears with a Q-tip. There are several parts of the game that investigate cancer, and the way that the cancer spread through the body of one of the protagonists, and actually uses a diagram to illustrate it. Someone in one of the reviews on Steam said something about how the game is a demonstration how capitalism can be a disease that infects your body. And that just occurred to me, when thinking about the Gramercy plant—that ambient dust gets into your lungs, your ears, it gets into every crevice of your body. This stuff becomes fused at the most intimate level with our biological selves.

Norco has received praise for the quality of its storyline, which is heavily influenced by the personal experiences of its creator, Yuts. (Courtesy of Geography of Robots / Raw Fury)

So much of Norco is steeped in autobiography in this way. How did you blend the personal within the fictional narrative?

YUTS: A lot of details are obscured or fictionalized, but the underlying narrative of the protagonist Kay’s mom dying of cancer is based on several family members who passed due to cancer, and then also seeing persistent illnesses in the community that I grew up in. That’s one dimension of it, the explosion would be another major one that colored it. Also having family who are employed by the various refineries up and down the river and having this implicit sympathy toward them in that they provide jobs, they provide stability, they donate computers to the nearby schools, etcetera.

Every dimension of my life growing up was colored in some way by the presence of the refineries. Growing up I was playing a lot of Nintendo games, and I was relating that landscape to what I was seeing in video games. I saw some kind of parallel between the kind of postmodern sci-fi media that I was consuming and what I was seeing in my hometown. I actually had a deep affinity for those landscapes—and I still do—and Norco, the game, is in part a reflection of it. I think they are beautiful. For a while I was kind of ashamed to admit it, but I think in a way it’s maybe helpful, because there is an internal fascination that a lot of us have for the macabre, and for destruction, and for things that are frightening. I was kind of in awe of just how devastating these facilities could be, especially because they were so present. They were almost like a leviathan or a god or something. A lot of people who live in Norco don’t even comment on the refineries. When you were going around taking photographs, Richard, I don’t know if this was part of your experience, but to a lot of residents it’s become so mundane that it’s not worth remarks. There’s this giant, fire-breathing dragon sitting in everyone’s backyard and no one talks about it.

Children playing in a residential yard adjacent to a Norco oil refinery, photographed for Engimatic Stream by Richard Sexton. (THNOC, 2015.0364.12; ©Richard Sexton)

RICHARD: Sure, I witnessed that. There would be children nonchalantly swinging on swings with the refinery in the background, and they’re just going about their lives.

YUTS: That’s right.

RICHARD: It’s like it’s not…there? It’s like the guy sitting on the park bench with the crane over his head, the way they hang the generators up in the air so nobody can steal them off the cranes. Sitting under that thing nonchalantly thinking, What could go wrong?

What I’m seeing in the game and in Richard’s photography, are aesthetic choices seeking to capture all that you’re both describing. How did you translate your emotional response to these landscapes into the visuals and the narrative framework?

YUTS: I started drawing the pixel art, and much closer to release I was feeling very overwhelmed by what remained to be drawn, and recruited a traditional painter who is now a very close friend, Jesse Jacobi, who helped refine a lot of the pieces. Most of the refinery landscapes were mine, but he has touched quite a few of them, and it was interesting to work collaboratively with someone who has no relationship to Louisiana, but through the rapid media of the internet was able to quickly acquaint himself with the landscapes, and I think he did a very great job where he needed to of reflecting the landscape of Louisiana. Aesthetically, creating the work and pixeling those landscapes, they’re labyrinths, they’re monsters, they’re gods, refineries are behemoths, massive and fascinating, so for someone with the sensibilities that I have, having consumed the media that I did as a child, it was almost a natural subject to study.

Creating the game really was a type of catharsis because I have such a conflicted relationship with Louisiana. I lived through Katrina and several other events—my childhood home flooded multiple times. I tried to process all of that, and loving the landscape, wanted to write what is, in my mind, not a dystopian piece of work but a love letter to Louisiana, meant to elevate in its own psychedelic way the aspects of Louisiana that I truly adore. Having people respond that this is a dystopian work is interesting because I really was just trying to tell the story of Louisiana as it is, with a few sci-fi flourishes that could assist with the narrative, and a lot of what people regard as particularly dystopian are things that are true. Like Richard was saying, people living hard-up against fence lines, residential displacement by refineries, floods, natural disasters, coastal erosion, all of that—those are all things that are everyday realities in Louisiana, and yet, I don’t think of Louisiana as a dystopia. I think of it as a complicated place, which is exactly what the game is trying to capture.

Norco has been praised for its distinct pixel artwork, which depicts the complicated relationship between heavy industry and the Louisiana environment. (Courtesy of Geography of Robots / Raw Fury)

Richard, the tension Yuts is describing reminded me of something you wrote in the introduction of Enigmatic Stream: “We are intellectually aware of heavy industry’s importance, are in awe of its power, and, at the same time, fear and loathe its existence.” What aesthetic choices did you make to convey that?

RICHARD: I did a few things that without apology glamorized the landscape. I shot at night a lot, when everything is lit up, and it just looks more enchanting, in a way, and intimidating, as well. For the most part, I just wanted to, in a true documentary sense, hold a mirror up. I learned a long time ago in this business, you can’t tell people what to think. You can show them something and let them form their own opinions about it. A lot of people bought the book because they wanted to give it to someone who worked at a plant. Chemical engineers bought copies as well as environmentalists, for different reasons. I think the landscape is an extraordinary human achievement. It’s good and evil all mixed together, kind of a metaphor for life.

Yuts, do you feel like Norco is holding up a mirror in this way, or are there specific things you’re hoping to convey?

YUTS: No, and I really appreciate Richard’s comments on this, because I feel similarly. It’s not in any way a didactic piece. It’s not intended to tell anyone how to feel on any level about anything. It is, in many ways, like he described, a mirror. My intention wasn’t to bemoan Louisiana and all of the difficulties that it presents. It was simply to convey that experience and to make sense of it in the context of the 21st century. There are other dimensions of the game where this is similarly true. It actually deals quite heavily in the later acts with online edgelord culture, and the rise of influencer cults and all of these other things. It handles those with a similar level of dispassion, which is they can be ugly, they can be beautiful, they can be funny—and it’s not meant to make any kind of normative assertion about these things. You’re not going to change anyone’s mind that way. I think that’s an ineffective way of producing art.

A view of a Norco refinery from a drainage canal off of Highway 61, photographed for Enigmatic Stream by Richard Sexton. (THNOC, 2015.0364.1; ©Richard Sexton)

There’s a strong undercurrent of decay that runs through both of your works—whether you’re talking about the infrastructure, or the environment, or cancer. Is there anywhere we can look for optimism when it comes to Norco and the surrounding areas?

YUTS: In the game, there’s a passage that tells the future of the town, which is that the Mississippi River changes its course to the Atchafalaya and the port becomes obsolete. The town is abandoned, and the refinery is abandoned because they can’t access the Gulf of Mexico. Within the confines of the game, it tells a pretty dire story about what the future holds, but in the larger scope of the game, I think there’s an underlying theme that there’s something new emerging culturally, and that it’s relevant for Louisiana as much as it is for anywhere else, because we’ve become so globally interconnected that there are new strains of faith, new kinds of religion, new kinds of communities coming out of the woodwork and assembling rapidly. Not to say that there’s a reason, particularly, for optimism—or pessimism—but that something new is on the horizon, and I think, [laughs] that’s as hopeful as the message gets.

RICHARD: I would like to be hopeful. I would like to think that there is way to solve all of this. I think most of the solutions that I’m hearing about involve even more technology, to fix the problems with the technology that we have, and I don’t know that that’s entirely the answer. The fact that there is a discussion, and the fact that there is concern over climate change and a recognition that there’s not unlimited supply that we can extract from the planet to do the things that we want—that is encouraging. There’s hope as long as people are trying to figure things out and understand better their place in the world. I’m older—I have two daughters, two granddaughters—so I may not live to see it, but I think future generations are going to be living in a world where we will have moved on from all of this in one way or the other, and I hope that it’s in a good way.