Three coats are displayed in a room of the Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibition In America: An Anthology of Fashion. One belonged to George Washington. One is the coat Abraham Lincoln wore to Ford’s Theater on the last night of his life. One, on loan from The Historic New Orleans Collection, was worn by an unknown young man enslaved by Dr. William Newton Mercer, a wealthy doctor with plantations in Mississippi and a residence in New Orleans.

“The coat is small, with a narrow waist and shoulders,” said Lydia Blackmore, THNOC decorative arts curator. “It might have been worn by a teenaged boy. We do not yet know their name, but the search continues.”

Both the Lincoln and Mercer coats were made by Brooks Brothers, America’s oldest continuously operating clothier. Founded in 1818, Brooks Brothers has outfitted generations of Americans, including 41 US presidents. The company presented Lincoln’s coat to the president for his second inauguration. The enslaved servant’s coat was one of hundreds sold through the company’s livery department on the eve of the Civil War. It bears a cloth tag from the manufacturer and silver buttons marked with a falcon crest, the same mark of ownership found on silver and china owned by Mercer.

Mercer had no direct heirs, and his estate was divided among a network of cousins in Louisiana and Mississippi. The greatcoat (overcoat) and a matching short livery coat ended up in a branch of the Butler family of St. Francisville, Louisiana. They came to the attention of researchers in 2011, when Adam Erby and Alice Dickinson, interns with the Classical Institute of the South (a program that has since joined THNOC and is now called the Decorative Arts of the Gulf South), cataloged the garments while working in the attic of Butler Greenwood Plantation.

The Historic New Orleans Collection subsequently acquired the coats from the Butler family, in 2013, and they underwent conservation to clean and stabilize the historic textiles. In 2015 they appeared in THNOC’s exhibition Purchased Lives, as well as recent traveling version of the show, and the livery coat was a centerpiece of The Collection’s 2021 exhibition Pieces of History, traveling most recently to the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts. Now, at the Met, the greatcoat is rubbing shoulders, so to speak, with Abraham Lincoln.

“The coats are important because they are rare examples of clothing known to have been worn by enslaved people,” Blackmore said. “They are extremely powerful objects. Standing in front of them, seeing their small size and their wear from history, makes you think of the people who wore them.”

A full-length view of the great coat with close-up images of its Brooks Brothers label and a button. (THNOC, 2013.018)

Searching for the wearer

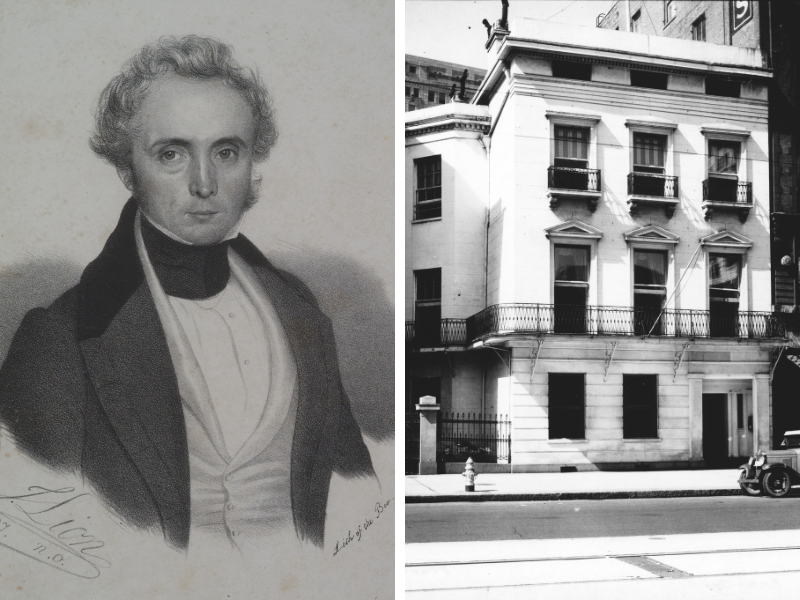

The search for the greatcoat’s wearer has presented a challenge to researchers like Blackmore and Jonathan Square, PhD, an assistant professor of Black visual culture at the Parsons School of Design in New York. Square oversaw the placement and interpretation of the greatcoat in the Met exhibition. A video screen below the coat, with text and images selected by Square, plays several slides containing information about the garment’s background, close-ups of its buttons, background on Brooks Brothers, a portrait of Mercer, and a list of people he enslaved—one or more of whom perhaps wore the coat.

Born in Maryland in 1792, Mercer moved to Natchez, Mississippi after serving as an Army doctor in the War of 1812. He married Anna Farrar, the daughter of a wealthy planter, who inherited thousands of agricultural acres and the hundreds of enslaved laborers who worked them. Mercer built wealth from those assets, at one point serving as president of the Bank of Louisiana. He built a grand city house at 824 Canal Street, designed by James Gallier Sr. and now the home of the private Boston Club. Mercer died in New Orleans in 1874.

During his research, Square delved into many archives of fashion, southern, and economic history, including THNOC’s Williams Research Center. “I’ve spent some time going through census records for Mercer,” Square said. “He was so wealthy, and a lot of his assets have been documented. He lived through several rounds of censuses.”

Though the greatcoat was discovered in St. Francisville, Square said he believes it was probably worn by enslaved servants at Mercer’s New Orleans home.

“Mercer was a bit of an absentee planter” after the middle part of the 19th century, Square said. “I doubt he had a big domestic staff for his Mississippi plantations, which makes me think the wearers were in his Canal Street property.”

Unfortunately, the name of the coat’s wearer is still unknown. “It’s kind of hard to narrow it down,” Square said of the search for the coat’s wearer. “[Dr. Mercer] owned hundreds of enslaved people.” Research continues.

A Jules Lion portrait of William Newton Mercer, ca. 1837, and Mercer's home at 824 Canal Street, ca. 1930. (THNOC, 1970.11.26 and 1979.325.353)

Unfinished stories about American fashion

About 100 examples of 19th and early 20th-century dress are featured in the Met’s In America exhibition, revealing “unfinished stories about American fashion,” the museum says in publicity materials. Among the garments is a gown from the mid-1860s by New Orleans–based dressmaker Madame Olympe Boisse—“the earliest American dress in the Costume Institute’s collection with a label identifying its creator.” A companion to the Met show In America: A Lexicon of Fashion, which focuses on 20th-century couture, the exhibition is on view through September 5, 2022.

The extent of Brooks Brothers’ trade in livery for enslaved people is a research goal for Square, who is working on a book about the Black fashion industry titled Negro Cloth: How Slavery Birthed the American Fashion Industry. The company’s records, however, are held by a private archive and, so far, have remained unavailable to him. Livery, including military uniforms, was an extensive part of the firm’s business in the 19th century, much less so in the 20th, Square said.

THNOC’s Mercer coats “have substantially furthered research related to fashion, retail, and enslavement in the Gulf South on the eve of the Civil War,” Blackmore said. “They epitomize our goal to document the material culture of the region and make it accessible to researchers near and far.”

The Lincoln coat (left, laid flat), Washington coat (center), and the Mercer greatcoat (right, laid flat) on view in the Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibition In America: An Anthology of Fashion. (Top and bottom images by Anna Marie Kellen, courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art)