1. Best laid plans

This plan, likely drawn by French engineer Ignace Broutin, offers a view of New Orleans when it was still a young French colonial city. The rectangular grid plan, oriented to the Mississippi River, was designed by French military engineer Adrien de Pauger in 1721, under the supervision of royal engineer Pierre le Blond de la Tour.

Plan de La Nouvelle Orleans, telle qu'elle etait le 1er. janvier 1732 [Plan of New Orleans as it was on January 1, 1732]. (THNOC, 1980.175)

Pauger and other French urban planners of the era were influenced by Enlightenment ideals of urban design, which sought to regulate the social fabric through rational planning. For French colonizers, the Americas offered a kind of laboratory in which to experiment with building a city from scratch. Fixed grids allowed for easier surveillance by eliminating hidden pockets in the urban space. Blocks were divided by social status. Streets closest to the river were reserved for prominent public buildings and residences, while more humble structures occupied the streets in the back of town. This division also reflected the local topography. Land closest to the river was the highest and driest, while land farther from the river was more prone to flooding.

French planners were also influenced by Spanish colonial urban design. Throughout the Americas the Spanish constructed cities in which buildings of church and state flank a central plaza within a rectangular grid. The central square for New Orleans was the Place d’Armes (today’s Jackson Square), the site of the first Saint Louis Church completed in 1727 and administrative buildings, including the city’s first jail and meeting house for the Superior Council, the colony’s main governing body.

In this detail of the plan, the church and administrative buildings are visible above the Place d'Armes. The river appears at the bottom. (THNOC, 1980.175)

Enslaved labor was used to build the earliest structures, which included army barracks, storehouses, and raised cottages made of cypress timber. Enslaved workers also built the first man-made levees and other municipal infrastructure.

The plan depicts a canal surrounding the city. Following the Natchez War of 1729, the engineer Pierre Baron proposed a moat to fortify New Orleans, a project begun but abandoned by 1732.

The original French colonial layout of the city remains the core of today’s French Quarter, with many of the street names the same as those shown on this plan.

2. A letter announcing some big news

In 1803 France sold the Louisiana territory to the United States in one of the most consequential land transfers in history. Robert Livingston, US minister to France, wrote this midnight letter from Paris to Secretary of State James Madison at the height of negotiations between the two countries. In the letter Livingston details the talks between himself, French diplomat Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord, and Treasury Minister François Barbé-Marbois. The letter contains the stunning news that Napoleon Bonaparte has unexpectedly offered to sell the entire Louisiana territory.

Robert R. Livingston letter. (THNOC, MSS 132)

Livingston had been deployed by President Jefferson to France to negotiate for the port of New Orleans and its environs, following news that Spain had transferred Louisiana to France. Napoleon intended to rebuild the French empire in the Americas. However, the French failed to retake the colony of Saint-Domingue, their most significant asset in the Americas, during the Haitian Revolution. With an expensive war with Great Britain looming, Napoleon chose to abandon the project and offered the whole of Louisiana to the United States.

In the letter Livingston informs Madison that he and his co-negotiator James Monroe will be meeting with Napoleon the following morning to present their opening offer for the sale. Because of delays in transatlantic communication, they agreed to the initial terms of the deal before receiving official word from Washington.

Concerned that his letter could be intercepted in transit, Livingston encoded key parts in a cypher. References to monetary values and intentions of the negotiators are concealed. For instance, Livingston writes, “We shall do all we can to,” and follows it with a string of numbers that translate to “cheapen the purchase but my present sentiment is that we shall buy.”

Robert R. Livingston letter. (THNOC, MSS 132)

3. An immigrant’s armoire

This mahogany armoire—measuring over eight feet tall and six feet wide—bears the label of the workshop of Dutreuil Barjon, a prominent New Orleans cabinetmaker. Barjon, a free person of color, was born in Saint-Domingue in 1799 and immigrated to New Orleans as a teenager.

Armoire by Dutreuil; ca. 1840. (THNOC, 2008.0088)

Between 1790 and 1810, about 15,000 Saint-Domingue refugees from the Haitian Revolution arrived in New Orleans. This group, which more than doubled the size of the city, was roughly evenly divided between white Frenchmen, free people of color, and enslaved Africans. The migration had a particularly significant impact on the community of free people of color in New Orleans, significantly increasing their population with individuals who possessed a broad range of professional skills and education, from teachers and journalists to artists and skilled craftsmen.

Barjon apprenticed under cabinetmaker Jean Rousseau, also from Saint-Domingue, and produced furniture from his Royal Street workshop in addition to importing pieces from Europe. Barjon’s son, Dutreuil Barjon Jr., continued his father’s cabinet business until the 1850s.

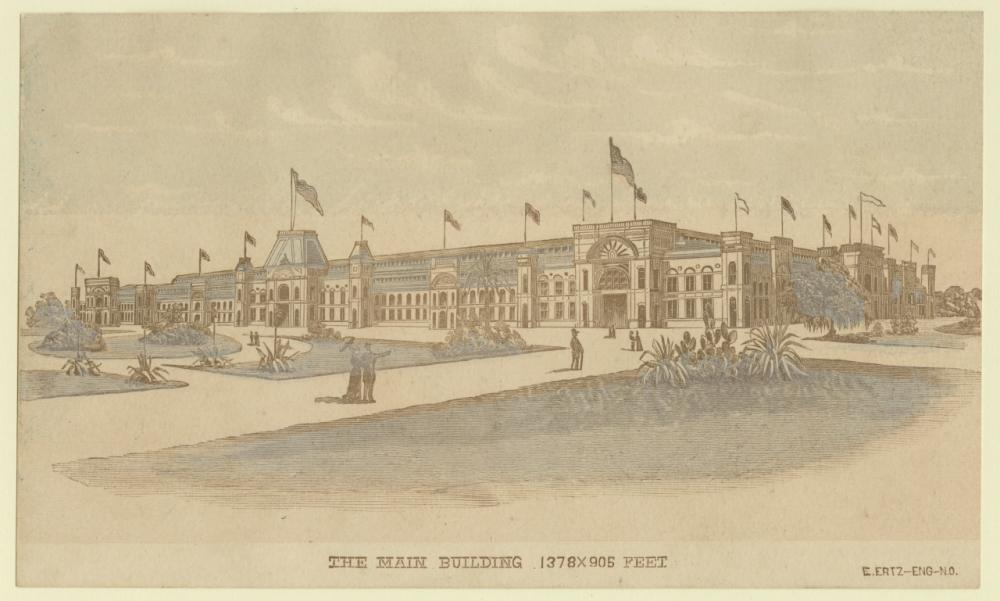

4. A centennial celebration

This print depicts the Main Building of the 1884 World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition. Sponsored by the National Cotton Planters Association, organizers hoped a world’s fair would help spur New Orleans’s economic and cultural revival in the wake of the Civil War. The year 1884 commemorated the 100th anniversary of the first recorded shipment of US cotton to Europe. With recent infrastructure improvements at the mouth of the river and the waterfront, there was widespread optimism that New Orleans could reemerge as a premier port city.

The Main Building, the World's Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition; ca. 1885. (THNOC, 1953.10.3)

The exposition was held on a plot of land known as Upper City Park, between Saint Charles Avenue and the river, on the former site of a plantation owned by Étienne de Boré. Accessible from the river or streetcar, the fairgrounds encompassed more than 200 acres and 15 exhibit buildings.

The fair suffered from poor planning and opening delays, which curbed attendance and financial returns. However, visitors reported an impressive array of cultural exhibits and modern inventions once the fair was underway. The Main Building contained 25 miles of walkways between exhibits and was illuminated with thousands of electric lights. At its center was an 11,000-person-capacity Music Hall, which became the social center of the exposition. A fan favorite of the fair was the program of performances by the 8th Cavalry Mexican Military Band.

Following the closing of the fair in the summer of 1885, the buildings were repurposed for another expo that opened in November 1885 on the same site—the North, Central and South American Exposition—in hopes of recouping financial losses. Later, the pavilions were disassembled and auctioned off for building materials.

The site of the fair is now a section of Audubon Park in uptown New Orleans.

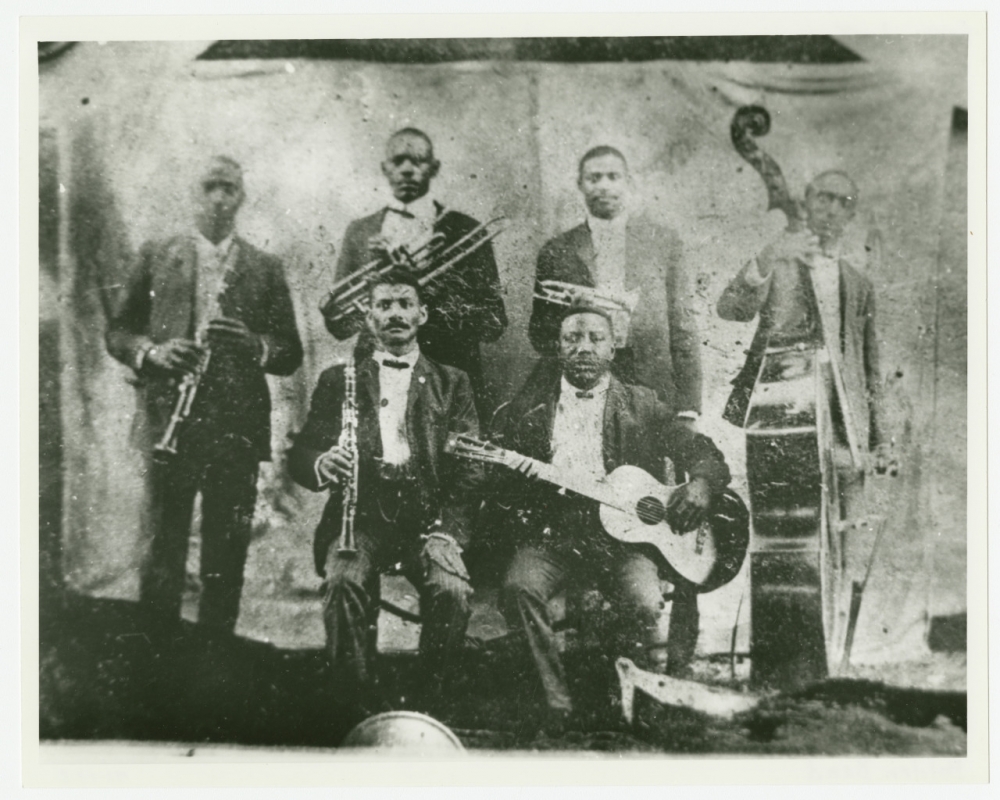

5. The only image of a jazz OG

This ca. 1900 photograph shows cornet player Buddy Bolden (standing second from left) and his band. Bolden is widely considered the first musician to use jazz elements on a consistent basis in his music. Leading one of the most popular bands at the turn of the century, he was known for his improvisation and loud, aggressive sound. Many early jazz musicians, such as Joe “King” Oliver, Bunk Johnson, and Jelly Roll Morton, were influenced by his style.

Buddy Bolden's Band; ca. 1990. (THNOC, MSS 520)

Sparse details are known about Buddy Bolden, and he left behind no recordings or published interviews. This has led to many myths about his life, such as that he cut hair at a barbershop and edited a gossip newspaper called The Cricket.

Charles “Buddy” Bolden was born in 1877 in the Central City neighborhood of New Orleans. Around 1895 he began playing with a regular band, and was soon able to quit his laboring job and work full-time as a musician, performing widely throughout the city at parks, parades, dances, and especially in the clubs and saloons centered around South Rampart and Perdido Streets.

Around the age of 30, Bolden began to suffer severe mental health problems. In 1907 he entered a mental hospital in Jackson, Louisiana, where he spent the rest of his life until his death in 1931.

This is the only photographic image of Buddy Bolden known to exist. The image has been reproduced widely, from an original photograph owned by trombone player Willie Cornish (standing third from left). This print was acquired by jazz devotee Bill Russell, whose extensive collection resides at THNOC.