For years, amid a cinematic landscape filled with sequels, reboots, and superheroes, cinephiles have lamented a lack of originality coming out of Hollywood studios. Here at The Collection, however, there’s no shortage of stories waiting to be told onscreen, and that’s where we, the Visitor Services department, can be of use to studio bosses.

As part of THNOC’s frontline staff, we have learned to sort the blockbusters, if you will, from the flops. Our team was eager to offer up five movie ideas—and suggest casting, because why not?—pulled directly from the annals of Louisiana history. Jazz, government corruption, wartime heroism, Mardi Gras Indians, and more—these are just a few of the themes and topics found in our holdings that can translate to the silver screen.

1. Mr. Larry’s Gallery

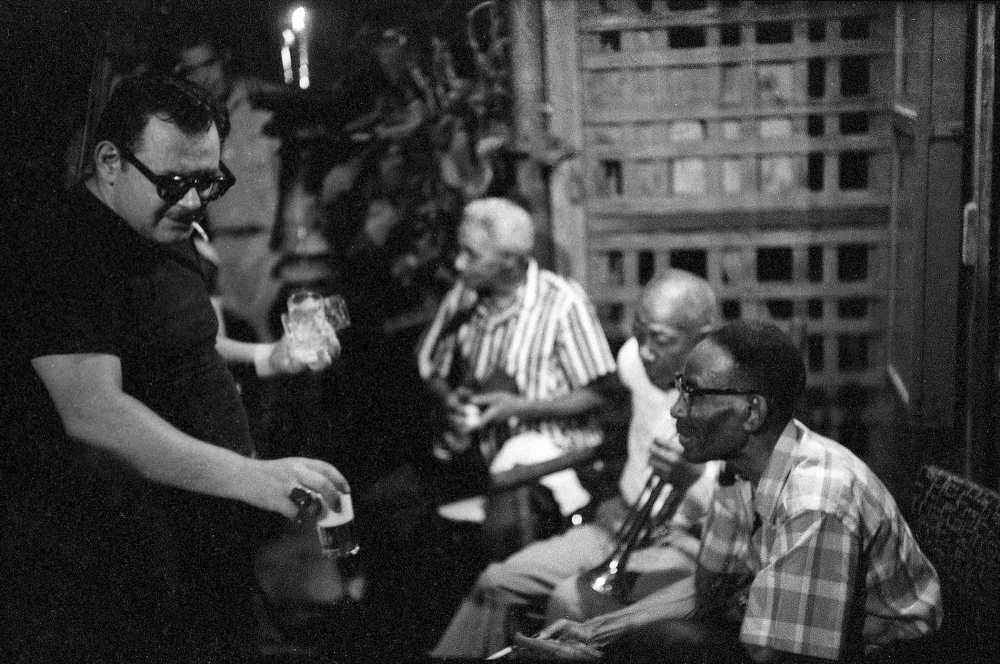

Larry Borenstein (left) is shown with George Lewis (far right) and two others in 1960 at his Associated Artists Gallery in the French Quarter. (THNOC, 1997.94.48 iv)

Larry Borenstein (left) is shown with George Lewis (far right) and two others in 1960 at his Associated Artists Gallery in the French Quarter. (THNOC, 1997.94.48 iv)

Story: All Larry Borenstein ever wanted was to run an art gallery in the French Quarter. Originally from Wisconsin and descended from Russian Jewish immigrants, Larry sold door-to-door from Milwaukee all the way down to New Orleans, arriving the night of the attack on Pearl Harbor. He immediately fell in love with the French Quarter and determined to incorporate himself into the neighborhood’s culture.

A lover of art and artifacts, Larry scraped together some money, befriended artists and business partners, bought a storefront, and filled it with art. But no one bought anything. When the gallery folded, he rented the space to another business, using the rent money to open up another art gallery, at which, again, no one bought anything. The process repeated itself until Larry owned about a fourth of the French Quarter.

In the 1950s he opened up shop at 726 St. Peter Street. Although the dearth of art customers continued to frustrate him, Larry noticed how successful the jazz buskers were in the street just outside his door. A lover of jazz himself, Larry made a deal with the busking musicians: play their music in his art gallery and bring their tipping listeners inside to buy art. Word spread among the black musician community, and soon traditional jazz musicians such as George Lewis, Punch Miller, “Sweet” Emma Barrett, Billie and De De Pierce, Willie and Percy Humphrey, and a host of others were getting together to practice and preserve traditional New Orleans jazz in “Mr. Larry’s Gallery.” It didn’t take long for Larry to realize that the customers were far more interested in listening to traditional jazz than they were in buying paintings or pre-Columbian artifacts.

In 1961, on the heels of a wave of national interest in traditional jazz and the older artists who had perfected it, the “rehearsal hall” became a full-blown music venue. Larry befriended and went into business with Allan Jaffe, whose family still manages the now-fabled Preservation Hall. William “Bill” Russell, noted early jazz historian, was said to be an in-house fixture in those early days. Also a lover of New Orleans jazz, he worked to contribute to the success of the Hall. Home to not only live performances but also a record label and the world-famous touring Preservation Hall Jazz Band, Preservation Hall helped to cement New Orleans’s reputation as the birthplace of jazz.

Cast:

Larry Borenstein: Jonah Hill

Allan Jaffe: Sean Astin

Sandra Jaffe: Mayim Bialik

Bill Russell: Alan Alda

“Sweet” Emma Barrett: Alfre Woodard

Billie Pierce: Taraji P. Henson

De De Pierce: Leroy Jones

Percy Humphrey: Wendell Brunious

Willie Humphrey: Michael White

George Lewis: Charlie Gabriel

2. How Bloody Was O’Reilly?

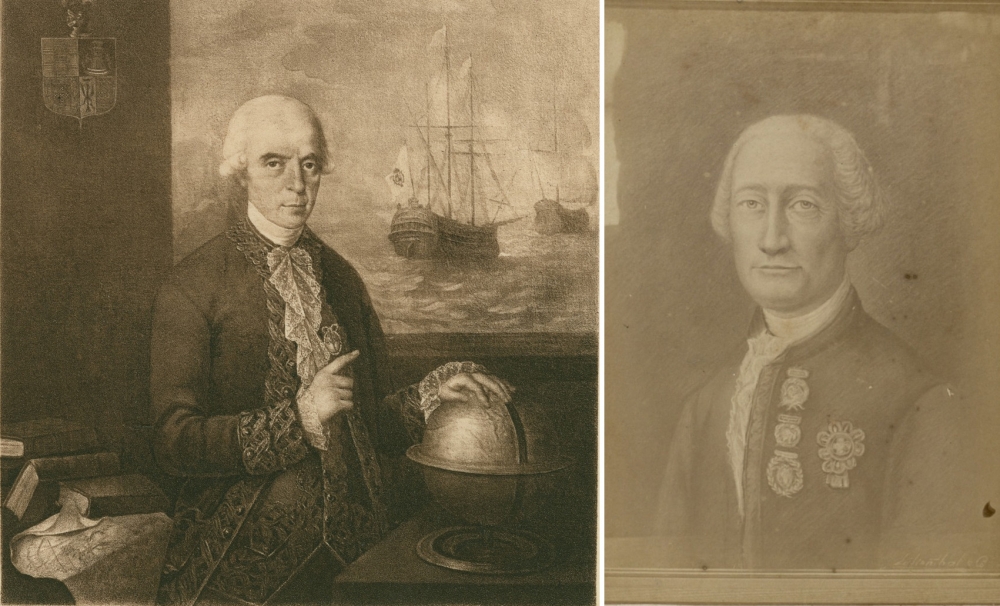

Louisiana's first Spanish Governor, Antonio de Ulloa (left), was unseated by a local rebellion. His successor, Alejandro O'Reilly (right), regained control of the colony and executed five local officials for treason, earning him the moniker "Bloody O'Reilly." (THNOC, gift of Thomas N. Lennox, 1991.34.12; THNOC, 58-101-L.3)

Louisiana's first Spanish Governor, Antonio de Ulloa (left), was unseated by a local rebellion. His successor, Alejandro O'Reilly (right), regained control of the colony and executed five local officials for treason, earning him the moniker "Bloody O'Reilly." (THNOC, gift of Thomas N. Lennox, 1991.34.12; THNOC, 58-101-L.3)

Story: Louisiana locals were not at all happy to learn that they had become subjects of the Spanish crown under the 1762 Treaty of Fontainebleau. A power vacuum emerged with the absence of the first Spanish governor, Antonio de Ulloa, who did not arrive to formally take possession of the colony until 1766. In the intervening years, local French Creole planters and merchants jockeyed for influence over the Superior Council, a major part of the government at the time.

Nicolas Chauvin de La Frénière, attorney general for the Superior Council, had been planning the creation of a Republic of Louisiana for some time. He convinced his fellow elites who, in turn, convinced others—New Orleans residents as well as citizens throughout southeastern Louisiana—to join in rebellion against the Spanish governor. On November 1, 1768, Ulloa was sent packing, much to the dismay of the Spanish king, Carlos III. Subsequently, Carlos sent Alejandro O’Reilly, an Irishman stationed in Cuba who had spent his life moving up the ranks in the Spanish military. In August 1769, O’Reilly arrived with 2,000 soldiers to curb the Louisiana insurrection and establish authority. He took the city without shedding a drop of blood, arresting La Frénière and 12 co-conspirators.

In October, they were put on trial for their actions against the Spanish crown. All were found guilty. O’Reilly agreed to turn a blind eye to the escape of the young, recently married Jean-Baptiste Noyan, but the young man refused. La Frénière and four of his compatriots, including Noyan, were executed by firing squad on October 25, 1769 (Frenchmen street is named in their honor). For those executions, the governor was dubbed “Bloody O’Reilly,” an epithet that remains in the minds and mouths of many New Orleanians. The remaining insurrectionists were given prison sentences. To calm the fears of citizens who had pledged to fight in the rebellion, O’Reilly issued a general pardon. During his short term as governor, he worked to reorganize the colony’s government and improve its economy, instituting a number of reforms.

Cast:

Alejandro O’Reilly: Ciarin Hinds

Antonio de Ulloa: Benicio del Toro

Nicolas Chauvin de La Frénière: John Cusack

Jean-Baptiste Noyan: Timothée Chalamet

3. Nobility

Jordan Noble is shown, left, in an 1880s photograph. A drum used by Noble in his 19th century military career is shown, right. (THNOC, 58-101-L.3.1; THNOC, 2019.0205)

Story: With a public performance record spanning over eight decades, Jordan Noble (1800–1890) was one of New Orleans’ earliest prominent black musicians and civil rights activists. Born enslaved on a Georgia plantation, Jordan and his mother, Judith, were purchased by enslaver John Noble in 1814. Noble was a lieutenant in the Seventh US Army Infantry, and Jordan was enlisted as the regiment’s drummer boy soon after.

On January 8, 1815, Jordan strapped a drum to his body and marched onto the Chalmette battlefield alongside John Noble, under the direction of then-Major General Andrew Jackson. Jordan famously played a long roll to cue the Seventh regiment, preparing them to engage the enemy.

Jordan’s lifespan was remarkable: in addition to being a black veteran of four separate wars in the 19th century, he was a witness and likely participant in the African drumming in Congo Square prior to the Civil War. In 1864, Jordan was an honored guest at the city’s Emancipation celebration held in Congo Square.

When he died in 1890, newspapers across the country ran an obituary celebrating his life and legacy. Today’s street music traditions evolved largely from military-turned-brass bands on the streets of New Orleans, and Jordan was certainly a pioneer in this regard.

Cast:

Jordan Noble (young): Jaden Smith

Jordan Noble (old): Jamie Foxx

Judith Noble: C. C. H. Pounder

John Noble: Harrison Ford

Andrew Jackson: Hugh Laurie

4. Any Hurt of Pestilence

The St. Roch Cemetery was founded by Rev. Peter Leonard Thevis during an outbreak of yellow fever in 1868. It is shown here in the 1990s. (THNOC, 2002.53.7)

The St. Roch Cemetery was founded by Rev. Peter Leonard Thevis during an outbreak of yellow fever in 1868. It is shown here in the 1990s. (THNOC, 2002.53.7)

Story: In 1868, New Orleans was gripped by a grave yellow fever outbreak. The city was, and is, no stranger to plagues. Yellow fever had scourged the Gulf Coast since at least the 1810s, but the 1868 outbreak, coming on the heels of the Civil War, was especially dire. Rev. Peter Leonard Thevis, who preached at the Holy Trinity Church (which is now the Marigny Opera House) sought to protect his parishioners from the outbreak. Thevis made an appeal to Saint Roch, patron saint of the diseased and disabled, who achieved his sainthood amidst the Black Death.

Thevis prayed to Saint Roch—commonly invoked against plagues—to heal the sick in his church, promising to erect a chapel in the saint’s honor. Miraculously, no one in Thevis’ church succumbed to yellow fever. Thevis, making good on his promise, laid the cornerstone of what would become the St. Roch Chapel on September 6, 1875, and the legendary St. Roch Cemetery soon sprang up beside it. For generations, the cured left tokens—also known as ex-votos—such as crutches, prosthetic limbs, and even dentures on the altar in the chapel. The ex-votos serve as an offering for a cure or improved health.

People still leave offerings today, in a gated side room next to the chapel. Those without access to the room are sometimes seen in solemn procession towards the chapel, token in hand to place inside or outside the gate. Each year on November 2, the Feast of All Souls, visitors can be seen flocking to the cemetery grounds to visit this shrine, some in ritual thanks to Saint Roch for good health and others on appeal for loved ones in need of a cure.

Cast:

Rev. Peter Thevis: George Clooney

Saint Roch: Christopher Walken

Supplicant No. 1: Kathy Bates

Supplicant No. 2: Octavia Spencer

Supplicant No. 3: Helena Bonham Carter

Supplicant No. 4: Lupita Nyong'o

5. Slats and Suits: The Story of Big Chief Tootie

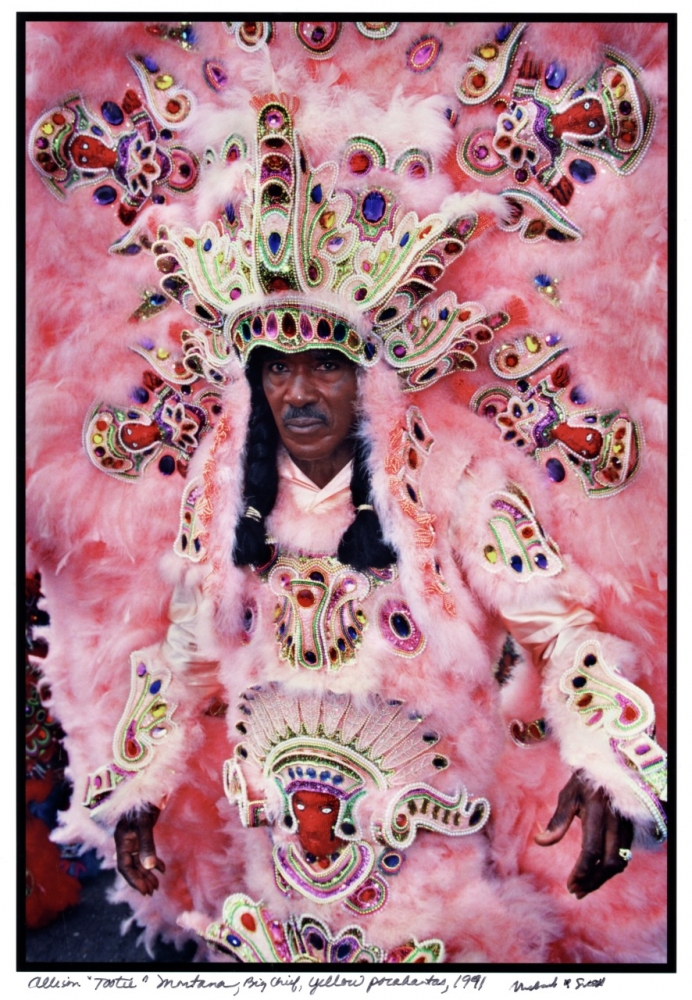

Allison “Tootie” Montana is pictured in a magnificent pink suit in 1991. (Photograph by Michael P. Smith ©THNOC, 2007.0103.2.122)

Allison “Tootie” Montana is pictured in a magnificent pink suit in 1991. (Photograph by Michael P. Smith ©THNOC, 2007.0103.2.122)

Story: Allison “Tootie” Montana, born in 1922, became one of the most revered and skilled Mardi Gras [black Masking] Indians on record. The Montana family legacy begins with Tootie’s great-uncle Becate Batiste believed to be the first documented Afro-Creole man to mask Indian. Batiste formed the Creole Wild West in 1880, and Tootie’s father, Alfred Montana, masked with the gang and eventually became big chief of the Eighth Ward Hunters.

By the time Tootie was old enough to walk he had already been exposed to the culture, but it would be another two decades before he picked up a needle and thread. It is not uncommon for Mardi Gras Indians to change positions or gangs throughout their masking careers. Tootie masked for the first time in 1947 with the Eighth Ward Hunters under his father; soon after, he broke off to position himself as big chief of the Monogram Hunters, and, later, as big chief of the Yellow Pocahontas. It would take another 20 years for Tootie to be recognized outside of the culture. In 1987, he received the National Endowment for the Arts’ National Heritage Fellowship. In 1998, he passed the torch of big chief to his son Darryl Montana.

For many years, Tootie’s frustration mounted as Mardi Gras Indian culture perpetuated a violent reputation. Knife and hatchet fights were common, and even today many old-time Indians will recount stories of violence between gangs. Tootie sought change by encouraging peaceful competitive pageantry—who has the “prettiest” suit—which has become a core component of the black artistic expression seen in the masking tradition.

On St. Joseph’s Night (March 19) in 2005, police barricaded an entire block full of black Masking Indians and their supporters as they fired shots to disperse the crowd. Two months later, while advocating passionately for his culture and against decades of police brutality, Tootie died dramatically and publicly in the New Orleans City Council chambers. He suffered a heart attack in the middle of his speech, virtually giving his life for the culture his family had helped to create.

Cast:

Tootie Montana: Danny Glover

Alfred Montana: Clarke Peters

Becate Batiste: Keith David

Darryl Montana as himself