Summertime, and the living is not exactly easy here in New Orleans, where the heat and threat of hurricanes drag on for months. But for three centuries and counting, residents have found ways to not only survive but thrive through the season. For some, it means getting out of dodge. For others, it’s about cooling off by any means necessary—30-minute snoball lines included. Here’s a look at summer in the city as seen through our holdings.

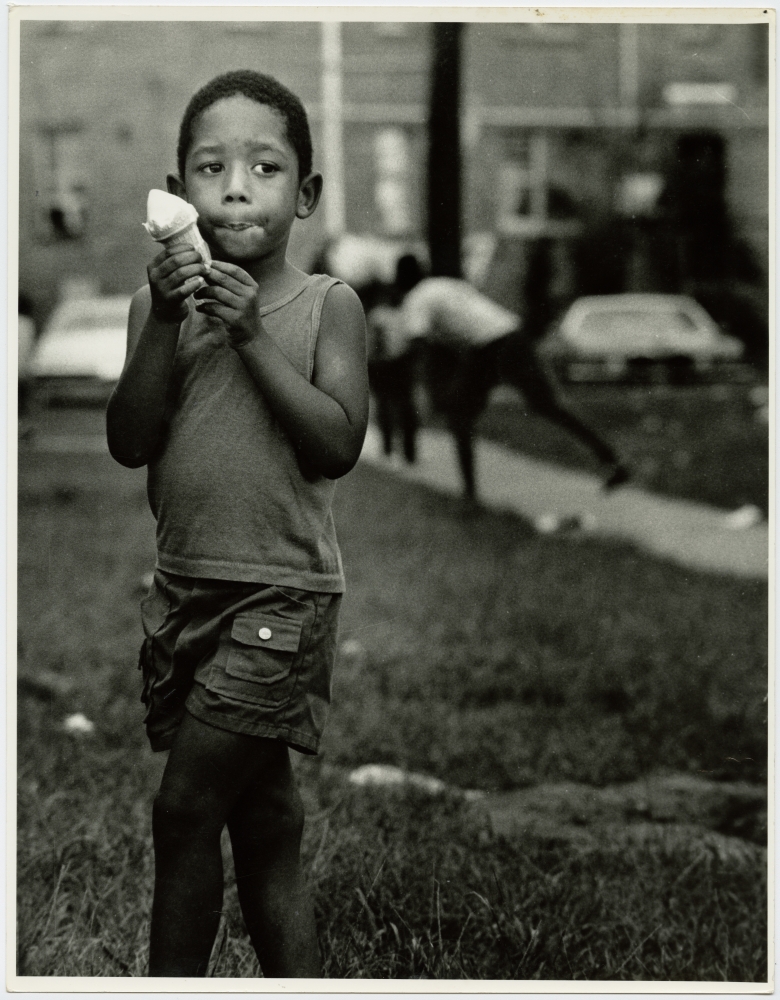

In this photograph by Harold Baquet, a boy eats an ice cream cone in the courtyard of the Desire housing projects in the late 1980s. (THNOC, gift of Harold F. Baquet and Cheron Brylski, 2016.0172.2.40)

Escape to the North

“Though a winter resort, New Orleans is preeminently a summer town—a city of galleried houses, of gardens, of flowers, and of shops which open wide upon the street,” writes Julian Ralph in an 1892 report from New Orleans for Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. While modern-day residents might scoff at the characterization of New Orleans as a “summer town,” Ralph goes on to describe the Caribbean–influenced architecture that makes summer heat tolerable—but just barely. Anyone who can afford to do so, he writes, leaves town: “The Americans . . . exchange the heat for the mountains and the forests. The wealthy among the creoles are apt to go to France, and there are many who divide the year thus.”

One option for people who preferred or could only afford to summer locally was the Claiborne Cottages, a Covington resort located “on a hill overlooking the lovely Bogue Falia [sic] River, flanked by lofty pines,” according to an advertisement in the St. Tammany Farmer. In addition to the “pure water,” proprietor Mrs. C. Wood of New Orleans promised good fishing, boating, lawn tennis, and bathing. In a bold statement, she claimed, “Mosquitoes almost unknown.” Lodgings cost $2.50 per day and $13 or $14 per week.

This watercolor painting, titled The Claiborne Cottages—A Summer Resort of New Orleans in the Piney Woods, by William Thomas Smedley, accompanied a report from summertime New Orleans in an 1892 issue of Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. (THNOC, The L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1952.19)

Snow and Ice to Beat the Heat

New York has its Mister Softee trucks, but New Orleans has its snoball stands. When temps are high, one can see groups of New Orleanians queueing loosely in front of matchbook-size storefronts, waiting for the sweet, ice-cold refreshment of powdered ice piled high and topped with brightly colored syrup. Entire books have been written about the joys of New Orleans snoballs (or “snowballs,” or “sno-balls”), such as Megan Braden-Perry’s Crescent City Snow: The Ultimate Guide to New Orleans Snowball Stands. Many residents stick with their preferred neighborhood spot, but others have been known to play snoball bingo, seeking to hit as many different stands around town as they can.

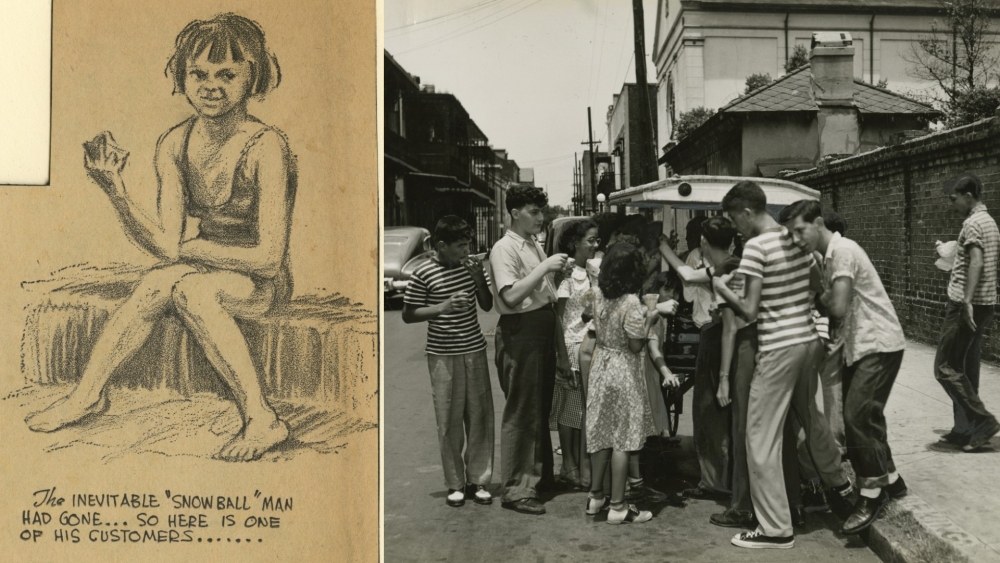

Left: In this 1936 newspaper illustration by McGowan Miller, a girl in a bathing suit clutches her snowball while sitting on the sidewalk (THNOC, 1974.25.20.138). Right: Before the ubiquity of snoball stands, the icy treats were sold from carts that roamed through neighorhoods, as seen in this late-1940s photograph of children crowding around a vendor on Chartres Street in the French Quarter. (THNOC, gift of Leonard V. Huber, 1976.139.98)

A Beach in the East

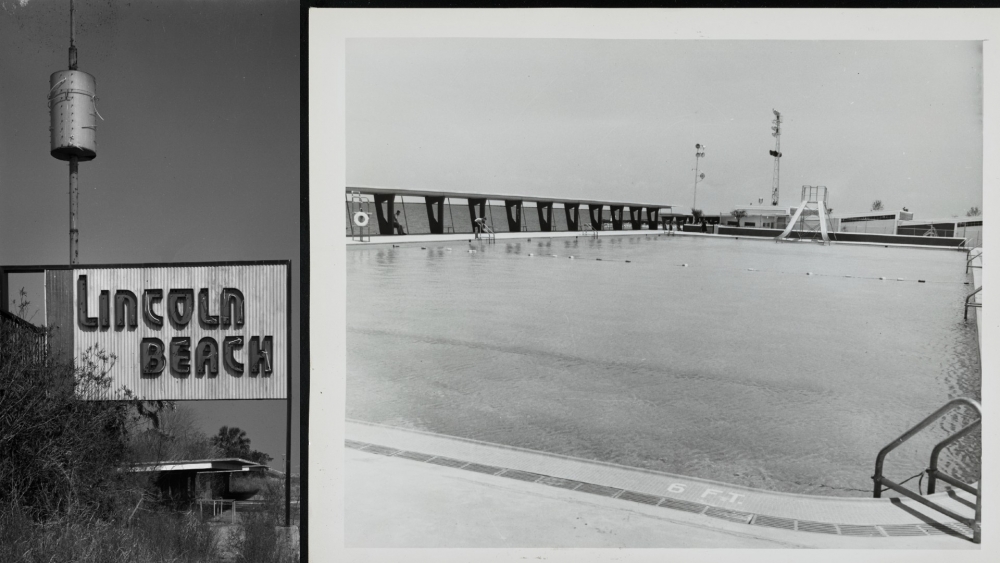

Lincoln Beach was Jim Crow’s answer to Pontchartrain Beach, the lakefront amusement park that catered only to whites during segregation. In 1954 the city opened Lincoln Beach on a 17-acre lakefront site in New Orleans East. Its amenities and diversions paled in comparison to the bigger, fancier Pontchartrain Beach, but it still had “two swimming pools . . . a bathhouse, a restaurant, and rides and attractions,” according to writer James Cullen’s history of the site for Antigravity magazine. For more than a decade it gave the city’s people of color a place to cool off in the summer. After the passage of the Civil Rights Act, in 1964, demand plummeted, as African Americans were eventually allowed entry to Pontchartrain Beach. Lincoln Beach closed a year later.

Lincoln Beach press photographs taken in 1955, soon after its 1954 opening. (THNOC, gift of an anonymous donor, 2022.0016.2)

Style through the Sweat

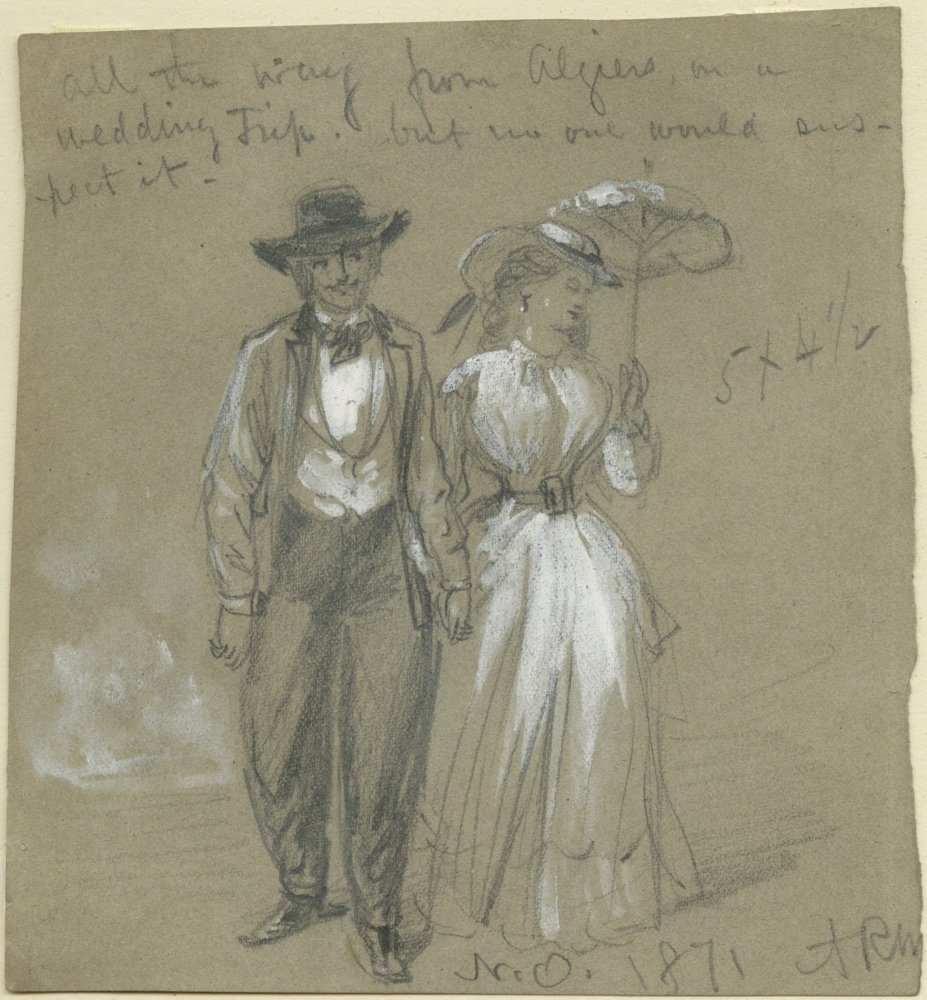

Today, New Orleanians survive summer with a wardrobe of tank tops, shorts, boat shirts, and rash guards, but decorum and textile technology were very different in the 19th century. According to Harper’s writer Julian Ralph, women of the 1890s kept a summer wardrobe of soft colors and “white dresses by the dozen.” Promenading out-of-doors was a must, to avoid the stultifying indoor climes. Hats, apparently, were optional: “They [New Orleans women] go about without their hats, in carriages and the streetcars, visiting up and down the streets. Indoors one must spend one’s whole time and energy in vibrating a fan.”

All the Way Up from Algiers, on a Wedding Trip, by Alfred Rudolph Waud, 1871. (THNOC, The L. Kemper and Leila Moore Williams Founders Collection, 1965.90.273.1)

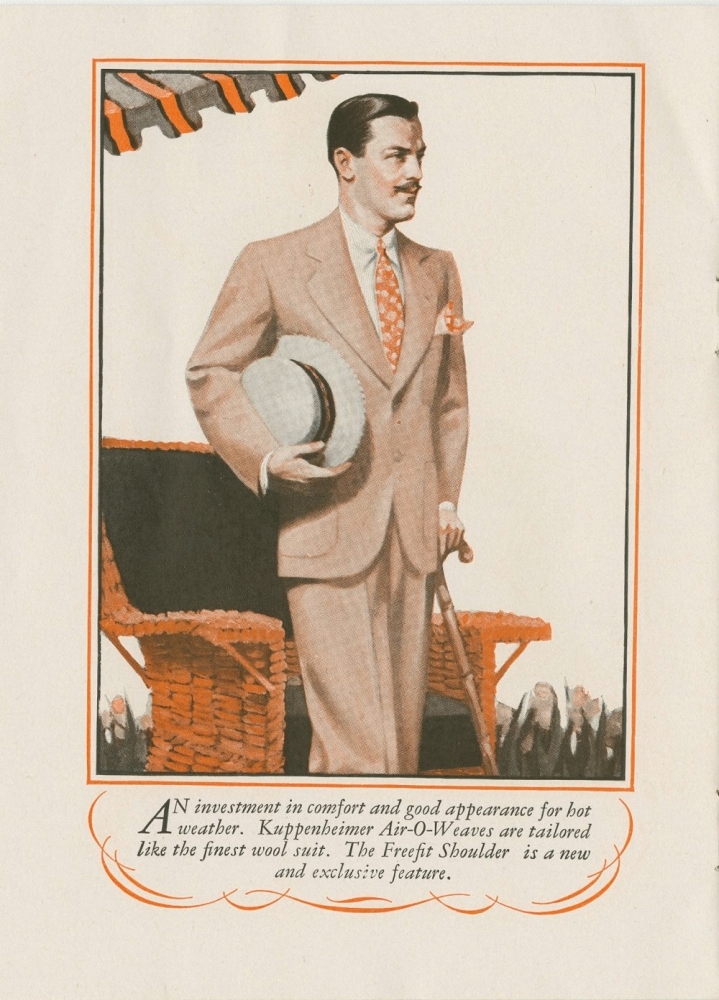

For men of a certain status, suits and jackets were the norm, and menswear stuck to this position for decades. Seersucker, a common choice for clothing enslaved people in the early to mid-19th century, entered the world of white menswear starting in the 1880s and has become synonymous with Southern summertime suiting. Other options can be seen in a 1926 brochure for the Chicago clothier Stevens Inc., which New Orleans department stores would have carried. One label, Kuppenheimer, offered buyers “an investment in comfort and good appearance for hot weather” with the introduction of “Air-O-Weaves,” a light wool suit with a relaxed shoulder fit. The illustration shows how to accessorize the ensemble, with a porkpie hat and cane—wicker lawn chair sold separately.

From “Good Appearance for Spring & Summer 1926,” a brochure published by Stevens Inc. (THNOC, 84-68-L.27)

A City That Floods

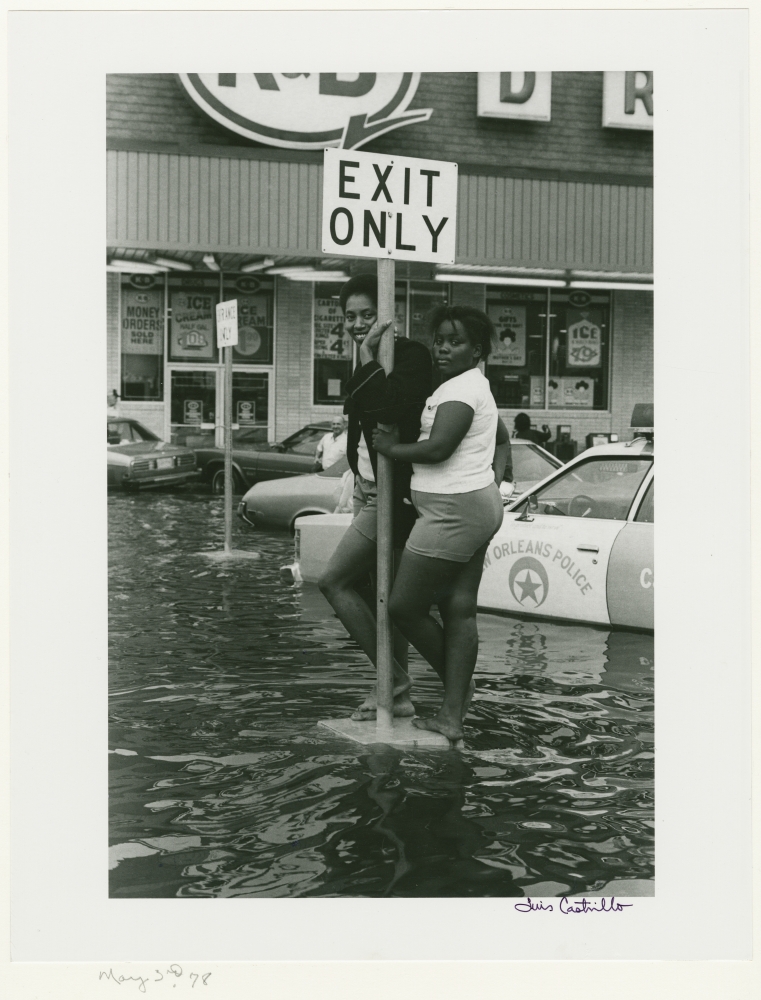

Street flooding has been a part of New Orleans life since its inception. Particularly in the summer, storms find a way to press pause on daily life, despite the development of the city’s levee and drainage systems. Residents are well-acquainted with the ritual of moving their vehicles to higher ground in advance of heavy rains.

In May 1978, cars at a K&B parking lot are seen huddled against the side of the drugstore to avoid stormwater, while a woman and child wait out the flooding on a signpost. (THNOC, photograph by Luis Castrillo, 1985.143.1)

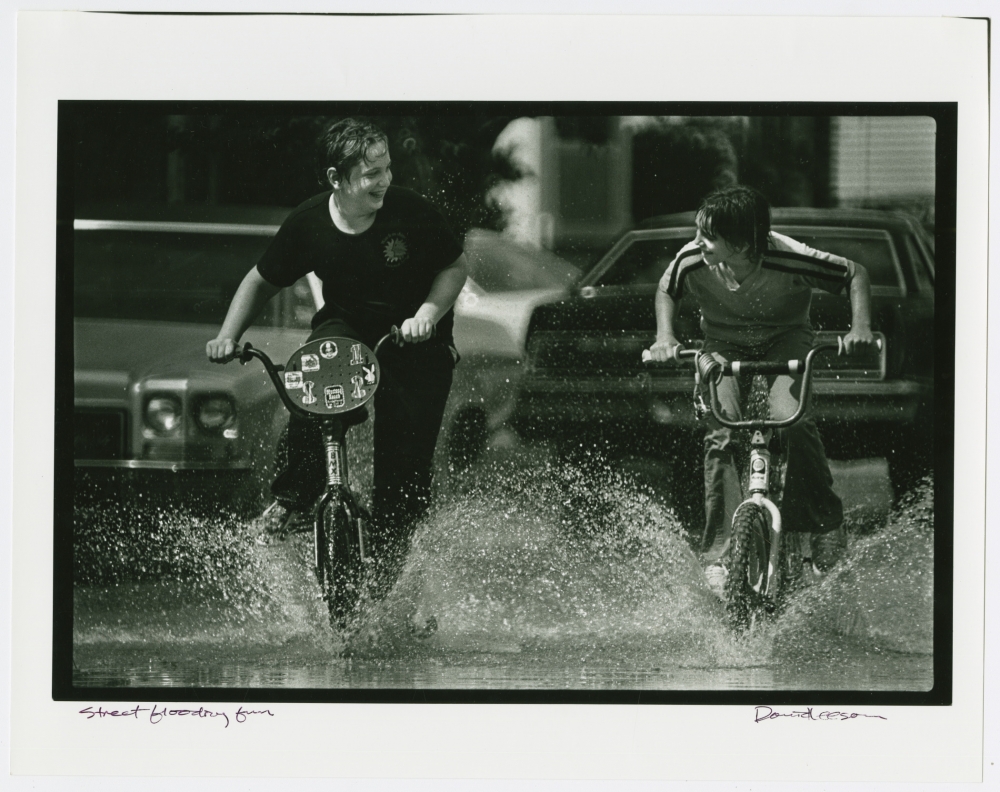

For children and the young at heart, street flooding presents an opportunity to step out of the ordinary. One perennial feature of summer storms is local news footage and photographs of people making the best of it, floating down their blocks in kayaks, canoes, and innertubes.

Boys on bikes stir up some wake on a ride through their soggy neighborhood in 1983 or 1984. (THNOC, photograph by David Leeson, 1985.148.4)

A Decadent End to the Summer

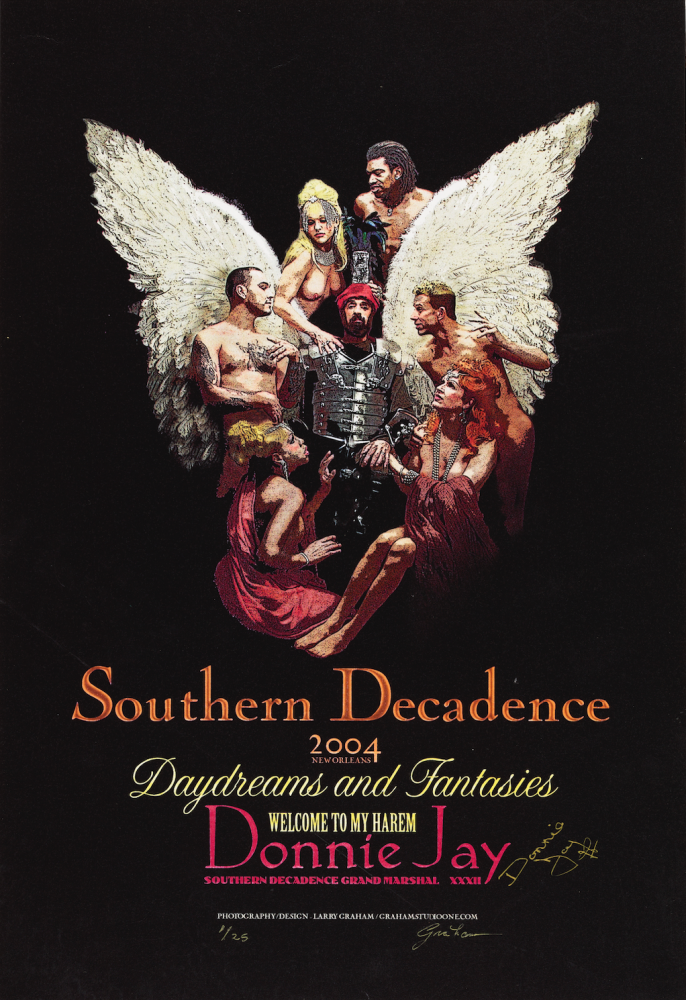

Labor Day typically marks the official end of summer here in the United States, but in New Orleans, the real capstone to the season is Southern Decadence, the annual LGBTQ+ pride weekend that features parties galore and the hottest, sweatiest parade of the year. As the event’s official history goes, “Southern Decadence began in 1972 with a group of friends who playfully called themselves the ‘Decadents.’ . . . All were young, mostly in college or recently graduated, and counted among themselves male and female, black and white, and gay and straight.”

One of the Decadents was leaving town to return to Chicago and bemoaned the lack of entertainment happening over the holiday weekend, so the group held a going-away party “marked by spiked punch and a lot of drug use, especially marijuana and LSD.” (It was the ’70s, after all.) The next year, the group began its tradition of parading the Sunday before Labor Day, soon adopting the New Orleans custom of assigning a grand marshal to lead the procession.

Fifty years later, Southern Decadence is a New Orleans institution and mainstay of the tourism economy, attracting thousands of visitors to the city to partake in the fun.

“Daydreams and Fantasies” poster for Southern Decadence, 2004, by Larry Graham (THNOC, gift of the estate of Robert Naquin and Marion Greeson, 2018.0336.15)

Banner image: Children swimming in the courtyard pool of Hope Haven and Madonna Manor, 1930s, by Charles L. Franck Photographers (The Charles L. Franck Studio Collection at THNOC, 1979.325.1136)